Alternative fees

Option 2 – project-based costing

Option 8 – discounted hourly rates

In this chapter I am going to describe one route which, when combined with your understanding of competitive strategy and market positioning, can fully restore confidence in your prices, both for you and for your client. It can make you look forward to discussing fees rather than dreading it, because your fees will have a solid, logical and mutually beneficial foundation. We just need to begin by talking about house painters.

Example

You have decided to have the outside of your house painted. In terms of my model I would categorise this as Relationship Advice. It’s not life threatening, but on the other hand you only want it done once, so there are more issues in play than just seeking the lowest price painters that you can find. With that in mind, you decide to obtain three quotes.

The first painter says that it will cost about £25,000. He hasn’t ever seen your house, but he has chatted to you on the phone. If you want, he will put the estimate in writing (if he does you will notice quite a few assumptions and conditions surrounding his ‘quote’). If you have any experience in these matters at all, then you will know that the actual cost will be quite a bit more than the quote. That’s because unexpected events will arise as he paints the house (rotten wood needing to be replaced, rain causing delays in completion and so on).

The second quote you receive, after this painter has visited your house and walked around it chatting to you, is that it will cost £2,000 a day for the painters to be on site and painting your house. How many days will the job take? ‘I don’t know’, says the painter, ‘because there are lots of variables, there could be some rotten boards that need replacing once we start the job, and of course the weather will have an impact as well.’ But not to worry, because at the end of the job the painter will total up the number of days taken and just multiply that by £2,000 to create the final bill. You instinctively realise that the painters have a great incentive to take their time painting your house, the longer they take the better for them.

The third painter is prepared to offer you an alternative fee arrangement, because he has both ‘master painters’ who have at least 10 years of on-the-job painting experience, and ‘apprentice painters’ who have up to two years of painting experience. As a result they can offer you a blended rate of £110 an hour which you will pay for both types of painter. How many hours will it take to paint your house? ‘Well’, this painter responds, ‘we will know that once we have finished the job, won’t we? Then we will just total up the number of hours we have worked, multiply it by £110 an hour, and there’s your total.’ You quickly work out that this painter has both an incentive to paint as slowly as possible and to use as many apprentices as possible.

At this point you order some paint and scaffolding and start painting the house yourself.

Let’s be clear on this. If other people behaved towards us when pricing work in the way that most service firms have typically behaved towards their clients, we simply would not put up with the cost uncertainty. The absence of any agreed and certain budget would be a deal breaker. Clients of service firms have put up with our charging by the hour because there were no realistic alternatives for most Relationship Advice. It was as if all the painters formed a cartel and agreed only to charge on the basis of time, and only to give quotes (which contain lots of conditions and assumptions which would allow an escape for the painter) if pressed to do so.

Of course, it might be different if you were an estates manager, who had to arrange for 100 houses to be painted each year. Or if there was a sudden and unexpected downturn in the demand for house painting, so that many painters were sitting around idle and were keen to get work at almost any price. In both these cases, basic economic theory tells us that the power shifts in favour of the client and the natural use of that power is to demand a move away from uncontrolled, uncapped charging by the hour.

In my view, the era of service firms being able to simply charge for time has ended in the post-recession drive for value. For Rocket Science, charging by the hour fails to reflect the value that the expert delivers, and while recording time may be a useful way for a firm to check up on how busy people are, the time taken should be merely one factor in the actual bill that is delivered to the client. For Routine Work, fixed fees have been (rightly) the norm. It is in the area of Relationship Work that time-based charging has largely remained, and it is here that it is under greatest pressure from the clients. Keeping that in mind, we will focus on Relationship Advice in this chapter and examine the alternatives and how we might align the interests of the firm and the client.

OPTION 1 – FIXED FEES

The usual demand from clients who are looking for an alternative to charging by the hour is to require a fixed fee. This is a perfectly natural reaction, although the wrong one in my view. Moving to a fixed fee for a single transaction involves risk: for the firm and for the client. The risk for the firm is obvious – that the work involved in the matter may greatly exceed the quoted fee. That risk is in fact magnified in practice by the following factors:

- The client has asked for fixed fee quotes from several competing firms, so the actual fixed fee ends up being reduced as the client plays one firm off against another. It starts unrealistically low.

- Firms themselves are often very poor at producing realistic quotes (having neither the historic data nor the skill to quote) – they almost always ‘come in low’ in any case, so the fee is never realistic for the actual work that will be involved.

- Firms often have little experience of project managing work against a fixed fee (which would require them to monitor cumulative spend against stages of the matter and adjust their work accordingly).

- The client can behave badly, not putting any effort into speed and efficiency, insisting on every tiny detail being covered and passing to the firm work that it would have previously carried out itself (because it has a fixed fee, so why not?).

- No matter that the actual transaction changes beyond recognition, the client can claim that the fee was fixed and is not to vary.

At first sight this seems to neatly transfer all risk to the firm from the client and appears to be a great deal for the client concerned. However, the reality is going to be somewhat different. When I have run exercises around this, I have discovered that clients are, quite instinctively, nervous about quality once they switch to a fixed fee for a task of uncertain size and duration. Of course, at one level, clients feel that they have bagged themselves a great deal. There is no risk on the client, is there? They have agreed a clear fee; there is no small print, so that is all that the client is going to pay. However, another part of their brain is cautioning: ‘But what if it goes massively over budget? Will the service provider still carry on working at a high level? Will I still be able to get hold of people, will they answer the phone and will they finish the job properly?’

These are proper concerns. When you combine a fixed fee with a partner’s typical inability to build a realistic quote (so that they always come in low) plus a bit of competition that is used by the client to drive the fixed fee lower still, you have a recipe for under-budgeting. The almost certain end result of this is that the deal goes ‘underwater’, which just means that the fixed fee has already been spent (on a time basis) so that any further work cannot be billed – it must be written off. This leaves work to be done, but no money to pay for it. It is likely that those people working on the matter will try to complete it with as little time expended as possible, will try to avoid client contact and, worst of all, may have to try to persuade others in their firm to work on the project after telling them that they cannot bill any fees to it because you have already blown through the budget.

In a typical service firm, people are going to behave in a professional manner. They will not walk away and refuse to help to complete the work – but it may not be handled to the same standard as a more normal matter where they are being paid for their efforts. That is particularly the case in firms which have given their people challenging budgets for recorded chargeable time, because that means that people working on matters that are underwater are going to risk missing targets and losing out on bonuses.

When partners are forced by their clients into agreeing fixed fees and then make losses on each transaction, a typical response is for them to start using assumptions and conditions attached to their fixed fee quotes (i.e. to stop them actually being fixed fees but to give the partner some escape routes if there is more work than anticipated). I have seen that reach somewhat epic proportions with a one-page fee quote referring to four closely typed pages of assumptions and exclusions. This is not a happy solution for anyone. The partner knows that the conditions attached to the fixed fee will quite likely be breached and so a higher fee will be charged, while the client will assume that the conditions would only be breached in extreme cases and believe it is most likely that the quoted fixed fee will be charged. There has been no meeting of minds about the actual fee and both sides are likely to be unhappy at the end. It is similar to the reason that I was taught, early on in my career, never to quote a range of fees – for example, ‘The fee for this work will be between £50,000 and £80,000’ – because the client hears £50,000 but the professional means ‘It’s going to be at least £80,000, probably a bit more’. This always ends with an unhappy client and a compromised fee at the end of the matter. So these ‘fudges’ around a fixed fee deal are not the solution.

However, there are situations where you can have fixed fees successfully in Relationship Advice:

- Where there is a stream of similar transactions so that you can effectively average the cost and use that as a fixed fee. Of course, that is the default situation for Routine Work, but it is not that common in Relationship Advice. So, if a single client has, for example, 10 transactions of a particular type each year, then rather than having to calculate individual fees you look at the last 10 transactions, average the cost and charge that (typically with a mark-up to reflect the value to the client of the fixed fee). You accept that you will win on some and lose on others, but that across the course of a year it should balance out (and if it doesn’t then you might adjust the fees for the next year). In theory, you can do this across several clients (so for example, Client A has one transaction a year, Client B has six and Client C has three) as the same mathematical averaging should apply. Doing this would enable firms to have a competitive edge with clients who favoured a fixed fee over an hourly charge. However, the clients would need to understand that they are in a pool and the fixed fee is fixed. If they encounter an easy transaction where the work is much less than the fixed fee then they can’t require a reduction, any more than someone who has insured their car can ask for their premium back at the year-end if they haven’t made a claim. So you may have some situations where ‘averaging’ works, but it is not likely to be the universal answer to the problem of hourly based fees.

- Using a retainer fee. This will be explained later in this chapter; it is where you agree a one-off annual fee covering a whole area of work for a client. For example, a client may have both Routine Work and Relationship Advice needs which it is sourcing from several different firms. One firm says, ‘If you give us all of this work we will agree an annual fixed fee to cover all of your needs’.

- Where the fixed fee represents a percentage charge based upon the value of a matter. In some sectors, it has been traditional that advisers’ fees are calculated as a percentage of the deal value. In such cases, the firms involved have so arranged themselves and their teams that they can (on average) carry out the required work within the percentage fee and still make a healthy profit. A cynic might point out that, when professionals have to work within a fixed fee structure, then they do. I won’t do that, because I think another factor is helpful for the professionals involved: that there is, intrinsic to percentage charges, an uplift over time because the value of deals goes up (typically) year-on-year. So as time goes on, 2% of a deal value rises and rises. That’s helpful.

Apart from these exceptions, I am against fixed fees for Relationship Advice. As I mentioned in Chapter 1, I used to describe a fixed fee to clients as the equivalent of their going into an operating theatre for an operation, but insisting upon only buying two hours of the surgeon’s time, and after that saying they wanted to be quickly sewn up and put back on the street. Because that was what was going to happen.

Let’s turn now to the best alternative, project-based costing (PBC), and how that, combined with knowledge about your competitive strategy and market positioning, can restore your pricing confidence.

OPTION 2 – PROJECT-BASED COSTING

PBC is the solution to introducing value into the client relationship for Relationship Advice and giving the client budget certainty, while protecting the service provider from unforeseen events. It’s not difficult or complex, particularly given that it is the method of pricing used for almost every type of project outside of traditional service firms and has been for many years.

In the real world it works for you and me when we are having our house painted or a new kitchen installed, and it works for corporations who are installing a new or updated IT system or for a public body having a school built or commissioning a nuclear power station. Partners in some service firms have traditionally challenged PBC by claiming that their work is more complex, more demanding (and expensive) than employing a painter. I get that. I understand that, at the start of a matter, the road ahead can be unclear, that no two transactions are exactly the same and that managing a cross-disciplinary team across many continents is intellectually demanding for a project that must be completed on time – but so is building a road bridge, a tunnel or a hospital, all of which would most likely be priced using PBC.

Creating and managing a price quote using PBC takes a bit more time than coming up with a rough quote and then charging by the hour. However, it’s not much harder to do and firms that cannot master this will be at a great competitive disadvantage over those that can. I became fully converted to PBC when a global client introduced a new set of rules for all of its professional advisers, which were beautiful in their simplicity and power. To paraphrase them, this is all that they said:

- When we instruct you on a piece of work, you need to send us a fee quote and we will then issue you with a purchase order number (a ‘PON’).

- When you interim bill for any work relating to that matter, you need to quote the PON on your invoice or we will not pay it.

- The total of your invoices for a matter cannot exceed the value attributed to the relevant PON.

- If you would like to invoice for an amount in excess of the relevant PON, you just need to get a new PON from us and you have to request this before you carry out work in excess of the original PON. We reserve the right not to agree to such extra work.

In plain language they were simply saying, ‘Give us a quote and keep to that. If something new comes up, check with us before you carry out any extra work’. I found it impossible to argue against these terms. Over time these rules were refined: for example, the client said that it wasn’t necessary for one-off pieces of advice under $1000 (but of course we could not then bill over $1000), and the client accepted that there were times when it was better for us to carry out some urgent work before we were given a new PON, provided we told them about it as soon as possible afterwards and there was a good reason not to ask in advance of the work.

I cannot see why any client should not impose these terms upon their service firm providers. At the service firm it radically alters how they behave when working on a matter. In practice I have seen clients who said that their bills dropped by 15–20% once they implemented PBC. As advisers we were expected to give a detailed quote and then to take notice of it as we delivered the work. However, it also meant that we did not reduce our hourly fee rates by even one penny (so we could make as much profit as we did before, or more because we had massively fewer write-offs).

Successful PBC requires the following.

Proper scoping

Here is a fundamental change in behaviour. In order to properly instruct a service firm the client needs to be clear about what the client wants them to do. Let’s go back to the example of the new fitted kitchen. The client really cannot do a good job of obtaining quotes if all he or she does is telephone three kitchen installers and have a brief conversation outlining the job. The kitchen installer needs to know the exact size and shape of the kitchen, the standard of fittings and equipment, the flooring and plumbing arrangements and whether they are doing all the work or not. They need to scope the job. The client may or may not have strong views on the kitchen and/or previous experience, but the installer needs to talk it through and explore the options so that they can produce a realistic plan and budget.

For proper scoping to take place, there needs to be an agreed process at the service firm end as well. For example, all those partners and others involved in a work type need to agree how work is to be carried out and what forms and procedures will be used at each stage. There is a real need for a standardised approach to the work or no two teams will scope, quote or deliver it in the same way. So you need to agree the list of questions that you will ask a client when they instruct you or request a quote, so that you know pretty much what they have in mind.

Creating a realistic quote

The construction of a detailed quote, with enough granularity for you to have confidence in the numbers, and for the client to be able to see what work is included and what is not, is the second stage of the process. A key element in being able to create realistic quotes is that you need to gather data on past transactions, create a database of these and have them available so that partners can use them when creating fresh quotes. This doesn’t need to become a huge, IT-heavy exercise. Even using junior staff over a couple of weekends to examine completed matters can start to create some useful data.

Stage 2 means creating a work plan and associated cost that covers all of the work from the start of the matter until its conclusion. Let’s anchor this in the new kitchen example. In stage 1 you talked about what was wanted where and about the various options available. If the client was new to this, you took time to explain what was involved, how long it would take and what the cost implications were of some of the choices being made. In stage 2 you produce a detailed written quote against that scope, which shows costs against each stage and might detail different options with different costs if it is relevant to do so (which will enable you to deal with any areas of uncertainty). How do you do this?

The answer is that you can only construct this quote if you examine previous work of a similar nature that you have completed, and use that previous experience to map the work involved and its associated costs. You don’t have to be very granular here unless you have easy access to the data. A first step might be to divide the scope of work into sections and cost each section by comparing it with previous transactions that you have carried out. You will start to see ranges of costs. So you might see:

| Transaction stage | Cost | Proposed quote |

| 1 | £17,200 to £24,100 | £20,500 |

| 2 | £2600 to £22,800 | £4100 or £20,700* |

| 3 | £4600 to £5800 | £4800 |

| 4 | £5700 to £8600 | £8600 |

| 5 | £11,400 to £13,300 | £12,200 |

| TOTAL | £50,200 or £66,800* |

In this example I have shown in stages 1, 3, 4 and 5 a typical range of costs incurred on previous transactions, and then you use your skill and judgement to see how the proposed transaction compares to the previous ones in order to come up with a reasonable estimate to put in your quote. In stage 2, you find from previous transactions there is a very wide range of costs. On further investigation you see that the ones at the lower end are all matters where there are no issues of a particular type – for example, there is an acquisition of another business but no tax issues. So here you give two quotes and say that the larger quote applies if the client wants tax advice (or the proposed transaction has issues that arise that require tax advice). This is how you deal with genuine uncertainties that cannot be clearly defined at the scoping stage. You show the client the cost without and with them. You do not quote a band of prices but you give two specific separate costs that apply in the two different circumstances.

This requires practice to get right and you are going to have to pay to learn. If you say that a particular stage of the transaction is going to cost £4860, but in actual fact you incur £6300 worth of time carrying it out, then you can only bill the client for £4860. It’s exactly how you would expect to be treated by a tradesperson who gave you a quote for a fitted kitchen. You don’t expect to pay £1440 more than the quote because the installer found it a more difficult job to carry out than expected.

One of the new skills that emerge once you start to use PBC is that you need to assemble a quote, which quite typically involves obtaining both a scope of work and an associated budget from colleagues or fellow partners in your firm. Gone are the days when, once the job has been won, colleagues from other disciplines in your firm pile in and perform their parts of the overall task with a focus on delivering the transaction on time, irrespective of cost. The lead partner suddenly becomes a buyer of professional services on behalf of the client! You will suddenly find lead partners negotiating with fellow partners over the size of their quotes compared to the size of the overall project. You might hear, ‘Our total fee for this job is going to be £112,000; we are not going to spend £35,000 of that on the tax aspects, think again!’ I believe it is this discipline that led to clients claiming that they were saving 15–20% of their spend. There was a discipline in creating a reliable and realistic quote and the lead partner was actually working on the client’s behalf in making sure that it was fair and reasonable. Imagine having your whole house decorated and never discussing the cost in advance with the decorator. Wouldn’t that mean that the final cost was much higher than if there is a rigorous scoping and costing stage in advance of work commencing? In practice you will find your clients awarding work to you on a much higher PBC quote than to a lower ‘guesstimate’ from a competitor. So a rough quote from a competitor of £100,000 would be (intuitively) rejected in favour of a PBC quote of £127,300 because the client understood that the ‘quote’ of £100,000 would be exceeded without any angst on the part of the competitor firm, but your quote of £127,300 was serious, deliverable and you are committed to delivering on it.

Agreeing the quote

What happens next moves us into value-based billing for Relationship Advice. The client receives the quote from you and one option is that they are happy with the scope of the work described and the accompanying fee, which means that the client considers that the value delivered equals the fee being charged. This should often be the case as you improve your skills in scoping and then quoting for pieces of work – but, of course, that is not always going to be the case. The client might consider that the fee quoted is too high. Either they will contact you about the quote, or you need to follow up with the client and check that they are happy. At this point a vast gulf in pricing expectations might emerge. This is a good thing, because it avoids the much more typical situation where there has not been a meeting of minds over the scope of work or the fee, but this is only discovered towards the end of the matter when fees are greatly in excess of the client’s expectations and both you and the client then have a real problem. Once you have a conversation with a client who was surprised by the size of your proposed fee, there are only three options:

- After carefully examining the work you are planning to do for the fee and discussing this with you, the client comes to the conclusion that the planned work and scope actually are necessary and agrees to the higher fee. Once again, this means that you have ended up with value-based billing.

- You find that the client expected a fee much lower than your quote. You explain that while you cannot do the amount of work that you had planned within the client’s budget, you could do a different job and effectively tell the client what parts of the existing scope you could deliver for the budget they have in mind. In other words, you cut the work to match the fee that the client wants to pay. Again, you have now reached a value-billing situation.

- You are able to convince the client that nobody could carry out a safe piece of work for their planned budget figure, and while you may be able to cut back from your initial quote you are not going to be able to do a reasonably satisfactory piece of work within the client’s budget. As a result, you propose cutting back the work to what you consider to be the absolute minimum, for a fee which is a compromise amount between your original quote and the client’s planned budget. If the client accepts your arguments, then again you have reached a value-billing situation where you agree to carry out work which the client values for the amount of the compromise fee.

What is perhaps most interesting about this negotiation stage is that clients become accepting of the need to vary the scope of work if there is to be a change in the fee quote. Previously, when round-figure guesstimates are provided to clients, they respond by negotiating in round figures as well. For example, after a guesstimate of £100,000 the client is quite likely to respond by saying they couldn’t spend more than £80,000, and then there might be a compromise somewhere between £80,000 and £100,000 – but all without there being any variation in the scope of work (which is wholly unclear anyway). Contrast this with the negotiation that occurred when a detailed PBC was delivered and the client said they didn’t want to pay £14,300 for the discovery element of a transaction, in which case you can reduce the amount of discovery work involved and reduce the fee to perhaps £12,200. Not only are negotiations being carried out with much more granularity, but they are clearly linked to changes in the scope – and that is the absolute mantra for negotiation of price. Any change in the price requires a change in the scope of work.

This third phase, when you seek to agree the scope of the work and your fee with the client at a very early stage (either before work has started, or in the first few days), is the real benefit of PBC. It means that you have agreed both your fee and the planned scope of work (or the revised plan scope of work agreed with the client), so there is no possibility of there being any argument about your fee at the end of the matter. Your fee has been agreed and this means you have the opportunity to avoid write-offs or delays when an unexpectedly high fee is received by the client. Perhaps most importantly, my experience has been that PBC was the highest driver of client satisfaction ever discovered. Partners, who devote such time, energy and expertise towards delivering a fantastic service for their clients, seldom realise that their efforts have counted for nought if they go over budget. It reflects very badly upon their expertise and professionalism.

The key issue with PBC is that once you have an agreed scope and fee, any changes have to be agreed in advance of additional work being carried out, and have to be in return for a clear and specified additional fee. That takes us to the fourth stage of PBC.

Delivery

In the delivery phase, the partner needs to project manage the work against the scope and the fee. This requires skills that many partners lack. While they may be adroit at managing a team in order to deliver the required solution for the client, they may well not have been trained in how to do that in an efficient way and having regard to the cost of delivery. It is much more common for the focus to be on achieving the desired end result, rather than checking on whether the project is running to a pre-agreed budget. There was a time when clients accepted that this was the priority, but those times have passed. In one case, a firm was planning to announce its new project management skills to its clients, only to find out that several existing clients expressed their horror at this, saying: ‘We had assumed that you were using project management already, and are surprised to hear you say that this is a new skill that you are introducing!’

There are a number of important elements for successful project management of both the work and its associated budget:

- You must have in place clear processes for delivery of the work with precedents, checklists and agreed procedures for every stage. You cannot have a system where every partner has their own methodology, or you will be unable to create accurate quotes and then deliver against them. Clients assume that firms already have all this in place so that there can be quality controls, so if you do not already have this, then this is the opportunity to capture best practice and document it.

- You need to be able to correlate work carried out against the relevant part of the budget, which is (surprisingly) not that common in standard time recording systems. There is little point in assigning time to ‘meetings’ or ‘drafting’ if it is not clear what part of the overall task is being handled. At its simplest, if you can envision the overall piece of work as having six stages, then you will have scoped and costed the work attached to each stage separately, and you now need to track the actual work carried out to those stages. You need to keep records of actual performance against budget because if, for example, you typically price stage one of a piece of work at £13,250 but it regularly costs £16,800 of time, then you need either to raise the price or find ways of being more efficient in carrying out stage one. This iterative process, where you continually learn and so refine your price estimates, is important and in fact is extremely widespread outside of the service sector.

- The lead partner on a matter may be great at their professional skill, but may well not be adept at keeping the whole team to budget. They may not even want to become involved in this management task. Firms essentially have two choices here: either to upskill the existing team with project management skills, or to recruit into the team ‘outsiders’ whose primary skill is project management. Certainly I have witnessed real failures where firms attempted to retrain experienced partners so as to add project management to their skill set. Attempt number two was then to train more junior members of each team because those people were still trying to ‘make their way’ in the firm and seemed much more amenable to learning something new. The alternative is to recruit ‘real’ project managers into the team (I slightly incline to this as a preference): the challenge then is for the rest of the team to be prepared to ‘be project managed’ and also to persuade clients to pay for the project manager (when they would, by default, have paid for a junior existing team member to do that work). I have heard that, over a relatively short timescale, clients will become prepared to pay for these separate project managers once they have seen at first-hand how much value they bring. The cost of these project managers may then be openly built into quotes to clients.

- Where delivery involves cross-functional teams, then the lead partner on the matter needs to keep all of the teams to their original quote and refuse to pay them a penny more (no matter how much time they have put onto the file) unless they have followed the correct procedures to obtain agreement from the client to an increase. So the lead partner performs a really crucial role in maintaining price discipline.

- PBC is not a fixed fee. It is a fee for the particular scope of work that has been agreed with the client. New issues (outside of the existing scope) may well arise during the course of the matter. In the past, partners typically carried out the extra work (maybe motivated by the desire to do a thorough job or to complete by a deadline) and then would seek to add on the extra cost at the end of the job. That felt fine for the partner, but surprised and annoyed the client. The promise of PBC is that, when additional issues arise, the client will be notified of the proposed extra work and of its cost before any extra fees are incurred. This means that the client stays in control of the scope and of the budget. When I first rolled out PBC at my own firm I had assumed that it was this forewarning that was important – that we would advise the client of the additional problem and its solution cost and, albeit after some internal discussions to allocate a higher budget, we would then be told to go ahead. I was wrong. In half the cases that I experienced, the client said, ‘No, don’t do the extra work and just keep to the original budget’. There were a variety of reasons for this. Some said that they would do the extra work themselves; some said that the relevant business unit knew about the issue and it had been factored into the price; others said that after thinking about it they had decided just to take a risk on it, and could we just write to them confirming that we had raised the issue but they had told us not to address it (so that we could not be accused afterwards of missing the point or of being negligent). How interesting, because in all these cases my previous practice would have been to carry out the extra work and discuss the extra cost at the end, and here were half the clients saying they didn’t want that. The other half were properly forewarned and agreed to a higher fee.

- To make PBC work, the professional has to be alert to ‘scope creep’, where the amount of work involved grows bit by bit so that there is more time recorded than can be charged to the client. This is really about keeping an eye on the original scope and comparing that with the work being carried out. Sometimes the client will ask you to add in something that was not in the original scope, or in response to you serving a notice of variation the client will acknowledge the extra work but ask you to do it for free as a favour. If this happens and you are prepared to agree to the client’s request, then I believe that there are two important steps to take. The first is still to prepare a proper notice of variation and associated extra fee and send it to the client together with a credit note for the same amount. This emphasises to the client that it is a real financial concession that is being given (and so that the actual write-off against the client can be recorded in your books, which becomes important when you are trying to compare the profitability of different clients). The second is to ask for a favour in return. This is the usual trading that we examined in Chapter 4. You will soon learn which clients ask more than others and be able to refuse: ‘I honestly can’t as I have already written off £12,800 of unplanned extras on this matter’; or you will look for truly valuable swaps: ‘I can only write off another £2400 if you can get me some work from your French subsidiary, so that I have something to show to my managing partner.’

- As you gain in experience your quotes will become more accurate, and (based upon your actual experiences) you might start to build in an amount on each matter for ‘contingencies’ and be able to explain to the client that it will be valuable for both of you. It means that you don’t have to request additional fees for relatively small changes and the client doesn’t have to keep getting authority to amend the budget (you need to be clear that if the contingency is not actually used, then it will not be billed).

- A quote prepared using PBC should not be an optimistically low figure. It should be a realistic fee that you expect to be sufficient in the vast majority of cases. You can keep yourself honest on this by keeping records and circulating them around the teams in the firm, showing in what percentage of cases you completed work within the original PBC fee. If it’s less than 80% of the time then you need to work harder on your quotes. If clients see that you continually have to increase your PBC quotes because ‘unexpected’ extra work arises, then they can properly call this a sham.

When facing real uncertainty

Even for firms that adopt PBC fully, there might be areas of work where the partners claim there is so much uncertainty about how it will turn out that it is impossible for a PBC quote to be prepared. Examples might be helping a client to address a sudden crisis, handle a piece of litigation or escape from an existing contractual obligation. You cannot know how this will play out, how any other parties involved will react and therefore whether this matter is going to last for a few days or over several years. So, how can you give an accurate quote for the cost? Again we are assuming that we are in the realm of Relationship Advice.

Here I found that clients do not expect you to have a crystal ball and be able to predict how the future will unfold. They are probably as aware as you are of the amount of uncertainty. However, that doesn’t mean that they see you as completely off the hook on cost so that you can now just revert to hourly based charging and work out the total cost by adding up all the interim bills at the end. What you can do is to use your skill and judgement to create a plan for the matter right from now until its end (be that final resolution, a mediated agreement or whatever). You can show the activity and cost on a month-by-month basis from now until that end. This enables you and the client to discuss the ideal solution. It acts like a decision tree and enables your client to make decisions about the potential future options available. Importantly, it shows the client the monthly cost all the way to completion (even if that is several years away), so the client can see the maximum likely cost.

Of course, as the matter progresses, new information will arise and there may be unexpected events. All that is required is for you to recast the plan, incorporating that new information or event, and show the new monthly cost up until completion. This may or may not mean that the client has to revisit the original decision. What it does mean is that the client has as much information as possible about cost and outcomes. It also means that the partner is under an obligation to keep matters on target against the plan agreed with the client and, just as with the other examples of PBC, it means the partner will have to put real effort into managing the matter against the planned scope of work and cost for each month. Yet again, the client will feel that they are in control and the partner will be putting serious effort into managing the cost. Contrast that with the more typical situation where, because the outcome is uncertain, the partner lapses into unfettered monthly billing, only being accountable for the actual work undertaken during that month, rather than the final total cost.

The payoff

If you adopt a PBC approach to your quotations, and then deliver against them, you will have much happier clients. They will also have spent less money per transaction because the scope will have been refined to suit exactly what they wanted (which can often be less than the partner would have planned), and then the partner will need to manage the work involved so that it matches the fee, rather than overrunning and hoping to collect extra at the end. All other things being equal, clients will be spending less money, and so you might wonder whether PBC is such a good idea for the firm. In my experience it is, not just because it avoids the huge number of write-offs that take place when the firm overruns the original quote and then is unable to recover the excess from the client. One of the biggest benefits was the winning of much more work from clients either because we had an amazing story to tell (backed up by facts and figures) when we were involved in a beauty parade, or simply because existing clients were more than happy to send us more work because we kept to budget (and none of their other advisers had ever done that!).

Of course this was not just earning a great reputation with existing clients, but they told others, who were equally impressed with this new approach. We regained our confidence and this was of huge value. When clients asked us to match offers from our competitors we refused to do so. We pointed out that those offers were unclear in scope and there was almost no chance that the competitor would bring in the work within the guesstimate they had given. The clients knew that we were right, and we saw many examples where we beat a lower-priced competitor with our much higher PBC quote simply because the client felt safe in our hands. In addition, our partners started to take pride in delivering within (even slightly under) the agreed budget. I well remember one of our best partners saying how pleased she was that she had brought in three extremely complex global pieces of work for a client within 1.5% of the original quotes. For partners to be taking real pride in delivering to budget, and not just being concerned about the quality of delivery, was pretty amazing.

OPTION 3 – BLENDED RATES

For some reason, procurement people seem pretty keen on blended rates, as do some partners. The idea behind a blended rate is relatively straightforward. In the simplest form, you take an average of the hourly rates of the various levels of staff involved in a piece of work. For example, if you have a partner on £400 an hour, a senior associate on £300 an hour and an associate on £200 an hour, then you could create a blended rate of £300 an hour and would say that all of these professionals will be charged at that amount, irrespective of whether the work is carried out by a partner or an associate. Alternatively, you may say that you anticipate a piece of work having 10% of partner time, 60% of senior associate time and 30% of associate time, which would lead to an average rate of £280 an hour. I think partners find this attractive because it involves offering the client what appears to be a lower hourly rate than the partner’s rate; and procurement like it because it enables them to compare one firm with another and then try to negotiate everybody down to the lowest figure that they are offered.

However, the end result is that the interests of the firm and the client are diametrically opposed. After agreeing a blended rate it is in the interests of the firm to use as many junior staff as they can (because they will be over-remunerated) and for the client to try to deal only with partners.

For repetitive areas of advice, I have seen blended rates operate relatively successfully (for example, where a client asked for small pieces of advice regularly). In such a case a PBC approach may be overly complex, simply because of the small size of each individual piece of advice that is needed. However, I think it a rather confusing solution.

OPTION 4 – CAPPED FEES

Capped fees are very similar to fixed fees, except they have the ability to be more amusing. In theory a capped fee sets a maximum that can be charged for a particular piece of work which is then billed (monthly) upon the basis of the actual time involved. If the total of the actual hourly charges is less than the agreed capped fee then the total of the hourly charges is billed to the client, but if there is an excess of total time over the agreed capped fee then the excess has to be written off. In that sense it is a one-way bet, which only the client might win if the actual work involved in the matter is less than anticipated. Just as with fixed fees, clients who are seeking capped fees will often obtain several quotes and then use the quotes to hammer the price down, so the final capped fee is often set at an unrealistically low level in any case.

These fees are amusing because if you ask partners who have carried out work on a capped fee deal if they have ever come in under the cap, then they laugh because they realise they never have (or almost never have). In other words, it is simply another way of dressing up a fixed fee deal, and in practice the firms almost always overrun and write off the excess.

So I would say no to a client who requests a capped fee because it has the same problems as a fixed fee in terms of getting matters completed to a satisfactory level once the deal is underwater. You might have an exception if the cap was set at a generous level and you then agreed to share savings under the cap 50:50. For example, if you expect a matter to cost £100,000, you might set a cap of £110,000 and then work hard with the client to bring in the matter under that figure. If you are actually able to complete the matter with a time charge of £90,000 then you would bill £100,000 to the client, thus sharing equally the saving of £20,000. Other than that, it is a matter of saying no to clients who ask for capped fees, but offering them instead a PBC approach which keeps them in control without unduly punishing the firm.

OPTION 5 – ANNUAL RETAINERS

An annual retainer is where a service firm agrees to undertake an area of a client’s work (or even all of the work that the client is putting out to external advisers) for a single annual fee which is typically divided into 12 parts and paid monthly. The client has the benefit of certainty and a fixed fee and may well receive a discount in return for passing all work to a single adviser. Imagine a client who has a panel of three firms and has an annual spend of £1 million across them: one firm might offer to carry out all of the work for a fixed annual fee of £900,000.

I have personal experience of setting up this type of arrangement, having negotiated and then managed a deal that provided services to a client for a single fee across more than 30 countries. I might say, ‘Don’t try this at home’ due to the difficulty of implementation in its first year, but in fact the arrangement became hugely successful for both parties and saved costs year-on-year for the client while being properly profitable for the firm. There are a number of factors that are preconditions to making retainer fees work:

- There needs to be a real atmosphere of collaboration between firm and client, so that both parties want to make it work and neither party is seeking to take unfair advantage of the other. This is important. I received some great advice from another client with whom we entered into a retainer fee, which was: ‘Don’t ever do this unless you know and like the client.’ With a retainer fee you have created an ‘all-you-can-eat buffet’ and you either need stop-loss provisions in the contract (so that the retainer is only fixed if certain conditions are met and total spend does not exceed a set amount), or you need a reasonable client.

- You need to use PBC internally to make sure that you control overall cost against the monthly retainer budget.

- After the fee is agreed you should launch a series of cost-saving initiatives which are now effectively in both of your interests. By continuing to cut the costs of actual delivery it will enable you to reduce the annual retainer fee year-on-year, whereas if you were making losses (the work carried out was greatly in excess of the annual fee) then of course you would cease to act at some point. That is why it is also in the interests of the client to make these schemes work. If the chosen firm makes losses it will bow out, and the client has to start again with new advisers.

Retainer fees reward first-mover advantage. If you are on a panel of three firms then it can be very much in your interest to talk to the client about an annual retainer fee if it excludes the other two firms. In my experience, only one person gets to have this conversation.

OPTION 6 – CONTINGENT FEES

A contingent fee is one which may or may not be charged. It is often requested by clients who are embarking on a risky venture which may or may not take place. For example, a client might be bidding on a project and will need substantial amounts of advice from all of its professional advisers in making that bid. However, other people may be bidding and there is no guarantee that the client will be successful. If they are not successful, they may want their advisers to waive all or part of their fees so as to reduce the cost of failure for them.

There are important factors that you need to consider if you are asked to provide work on a contingent fee basis. More importantly, what are the chances of failure? The more speculative the matter is for the client, the higher risk the professional adviser is taking by offering a contingent fee, and where there is high risk it is much more reasonable for the professional to require an uplift in fees if the matter proceeds. A useful way of structuring this, which shows that the adviser has ‘skin in the game’, is to have a staged contingency which will limit exposure. For example, you might divide a transaction into four stages in the knowledge that it could fail at any of those stages. You could then offer to have your fees on stage 1 as being 100% contingent, but if stage 1 is passed then fees for stage 1 are invoiced to the client. Stage 2 is 70% contingent, stage 3 is 50% contingent and stage 4 is 25% contingent. Alternatively, you might just say that 40% of your fees are contingent on a transaction, having worked out that the 60% this leaves will more or less cover your costs.

Whatever route you take, there should be a reward to reflect the contingency that you are taking. For example, you might say that in return for having part of your fees contingent, should the matter proceed to completion then your fee will be the budgeted amount (calculated using PBC) plus 30%. You need to calculate the uplift based upon your assessment of the risk that you are taking. The greater the risk, the higher the uplift. For example, if you believe that there is a 33% chance that the matter will abort (so that you will receive no fee at all) then the fee charged for success should be increased by 50%. You can see this by looking at an example of a matter where the fees are going to be £100,000 but you are asked to make them contingent (and your best guess is that there is a one-third chance that the matter will fail). In normal circumstances, if you had three of these in a row, then you would have earned £300,000. If one is going to fail then you need to earn £150,000 on each of the others to get back to where you started – which means a 50% uplift.

If the contingent element is 50% (i.e. if the matter aborts you will charge half the accrued time) then the required uplift is 25%. In all cases I have assumed that the matter becomes abortive after all of the work has been carried out. If that is not the case, then that too reduces the required uplift. As you can see, you may need help in calculating the variables in order to offer a contingency and an uplift which is fair to the client and commercially realistic for you.

There are areas of work where contingent fees have become the norm, but they can be dangerous for the firm if too much of its income is put at risk. In addition, there should be an assessment year-on-year of the impact of contingent fees and their associated uplifts – in other words, was it worth it? If not, they need to be adjusted to make sure that it is. I understand that in times of famine, clients become less prepared to offer an uplift in fees for success, working on the basis that many firms will be prepared to offer contingency. However, I do believe that this is a line the partner has to draw because without an uplift, and given that some of these transactions are going to fail, it means that on average a potentially large percentage reduction has been given. That reduction could mean that one abortive matter cancels out all of the profit on the work that is successful and completes.

OPTION 7 – SUCCESS-BASED FEES

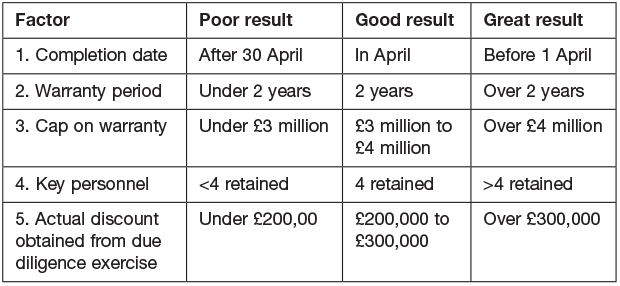

Again, some clients seem to like to link the final fee charged to the outcome of the particular transaction being advised upon. As we have seen, that link is best practice when it comes to Rocket Science, and can be a mechanical variation for Routine Work (for example, the fixed fee is increased by 1% for every day saved in the timetable of the matter). For Relationship Advice, one good approach is to create a ‘poor, good and great’ table which documents what different outcomes look like, and offers an uplift or discount of 20% (or whatever percentage is agreed in advance) tied into descriptions of particular outcomes. A simplified example is shown below for an acquisition, where time has been taken to identify (in words) what the different results look like:

In practice this means that the client and the partner must spend some time at the start of the matter so that they can document the most important factors for the client and describe the different levels of outcome. This is really valuable for the partner because they might guess what those factors are and may well not get them right. Having them documented and circulated to the whole team working on the matter makes a real difference to their understanding of what a great result is, so that they can really direct their efforts to achieving that. Once the matter is finished, the client and partner meet again and the client decides how the actually achieved outcomes measure against the table, on the basis that if they are all ‘poor’ then the PBC fee is reduced by 20%, if they are ‘good’ the full PBC fee is paid, and if they are ‘great’ then the fee will be the PBC fee plus 20%. Typically, the outcomes will not all be in one column so the fee might be increased by, say, 7% for partial achievement of ‘great’. This is a great way for advisers to learn much more about the client’s objectives and become better and better over time at delivering against them.

Due to the overhead in time of putting these types of success fees together, I consider they are appropriate only where the client is keen on them and the transaction is large enough to merit the time. If those two conditions are met then they offer a real opportunity for the firm to dramatically increase its profitability and to have value-based billed for Relationship Advice.

I have seen some firms enthusiastically embrace combinations of contingent and success fees and make them part of the skill set that they offer to their clients. Doing this successfully requires real pricing sophistication, the ability to understand the risk in the contingency and the value of success to each individual client, but armed with that skill the firm has something very differentiating to offer its clients. We will address this in more detail when we examine the issue of pricing capabilities in Chapter 11.

OPTION 8 – DISCOUNTED HOURLY RATES

You might find it surprising that I am writing about discounted hourly rates in a chapter about alternative fees. It’s because, in response to requests from clients for ‘alternative fee structures’, I have quite regularly seen responses offering a discount off the planned hourly rates. So, for the sake of clarity, it’s worth explaining: 10% off hourly rates is not an alternative fee proposal; nor is 15% off.

However, what about clients’ demands for immediate discounts off hourly rates? Clients are going to demand them, in particular if they are large clients (or, in my experience, if they are US clients). For example, I have heard: ‘We would not deal with any adviser who does not offer us at least 10%/15% off their standard rates.’ The primary solution is to have a standard rate card which allows for discounts without causing undue damage to profitability (again a topic addressed in Chapter 11). Effectively your headline rates have to start high enough so that you can cope with clients who insist on 10% or 15% as a starter discount. You should also tie the discount given to a particular level of spend, so you have a right to end the discount if fees do not reach a pre-agreed level. My response to such demands has been to say that this level of discount is reserved for clients who spend at least, say, £500,000 per year and that the rates will be revised if the client does not reach that level within a set period of time.

THE CONFIDENT PARTNER

By this stage I want you to start having some real confidence in your pricing. This comes from:

- Using cost-plus pricing so that you understand your breakeven point or the floor under which you should not drop.

- Positioning your firm against its most direct competitors, understanding why you are going to charge more than certain firms and having good reasons that justify the premium (or adopting a lowest price strategy and understanding the implications of that for your cost base).

- Segmenting your offer of services (more about this in Chapter 8) so that you don’t simply have one level of service, but you have varied services and prices that appeal to different segments of the overall marketplace.

- Being proud to use PBC as the main method of calculating your prices for Relationship Advice, creating budgets in which you have real confidence of achieving; using value billing for Rocket Science and reserving fixed fees for Routine Work.

With this new level of confidence, you will be ready to look at how you can better understand how clients value your services and use this as a way of creating more value and higher prices, which is covered in Chapter 8. Before that, I want to examine some common pricing tactics and how you might use these in your business.