Pricing controls and capabilities

Building pricing capabilities by Robert Browne

The role of pricing in the organisation

BUILDING PRICING CONTROLS

When we come to implementing better pricing in service firms, paying attention to the most basic sales and delivery behaviours can have a substantial impact upon the prices that can be achieved and the profit returned. This may be due to the high human involvement in the design and delivery of services – it’s not like running a production line for physical goods where uniformity is more easily implemented. The fact is that remuneration policies in service firms are usually targeted on increasing income through sales, rather than maintaining prices. A great starting point is to tackle these systemic issues, and then to use that as a foundation for developing true pricing capabilities which will enable the firm to create the right services and to reap the full rewards for its efforts.

When consulting in service firms, I usually ask at board level to set a profit improvement target of at least 5% across a two-year period. I show them that achieving this would dramatically improve cash returns. For example, a firm with a turnover of £10 million gains £500,000 in profit each year, and one with £1 billion can expect an extra £50 million in profit because these improvements can go straight to the bottom line without increasing costs (for simplicity I am assuming no customer attrition). If these projects failed to achieve the target and delivered only 2% this would still mean a £200,000 or £20 million increase in profit, which is not a bad reward for failure.

Let us begin by looking at what should be some of the easy wins of the pricing world. We’ll then move on to explore how pricing can become a strategic capability for service firms, just as relevant and important as finance or marketing and worthy of talented resources and the attention of boards.

UTILISATION

The income and profitability of any firm is as much linked to utilisation – what percentage of available saleable hours are sold each month – as they are linked to the prices charged. Even if you are selling fixed price services, there is a huge difference between people who have enough work to be busy all of the time, or just enough for half of their time.

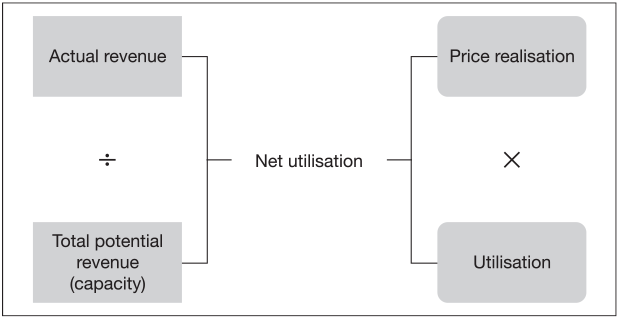

The equation is shown by Figure 11.1.

Of course, the drive to sell the available time is a sensible one. Whatever time is not sold each day is lost forever. It cannot be carried forward. The important issue is to understand that it not always the right answer to base your actions upon maximising utilisation in the short term, as that can lead to very damaging pricing outcomes over time. It is similar to the actions that you see when firms target a growth in percentage market share and then do whatever it takes to reach that share. Whatever it takes usually means discounting until growth targets are met (to the great detriment of total profit).

Figure 11.1 Calculation of net utilisation

Improving utilisation by dropping prices is undeniably a rational thing to do in terms of growing income in the short term. This partly explains why partners are quick to drop prices to keep their team busy (although it is also because teams that are quiet are hard to keep together and are well-motivated). Let’s look at the maths to see the dramatic effect: I will use the example of a team that is budgeted to achieve income of £200,000 a month and has overheads of £160,000, giving a monthly target for profit of £40,000 (20% margin). In January and February income has been running at £150,000 and that is also the anticipated income in March. However, the partner in charge he/she is given the opportunity to win an additional piece of work that should be priced at £100,000, but he/she can only win it if he/she offers to do it at half price. He/she does this and the work is carried out and billed in March, so that total income in March lifts from £150,000 to £200,000.

As we can see, this clever partner has more than made up for the £10,000 of losses in each of January and February, and the profit for that year is (all other things being equal) going to be £50,000 higher than if the partner had turned down the half-price piece of work. At the margin, extra income falls 100% into profit (or into reducing losses). This is often referred to as marginal pricing.

However, this sugar rush of relief to an underutilised team has some very unfortunate side-effects. At the client level it teaches them that amazing discounts are available when you ask for them (so, of course, they will absolutely ask again), and it can be very difficult to obtain good prices on services delivered to that client in the future. More worryingly, the client may tell others about their good fortune and that could lead to other clients and prospective clients expecting similar discounts (or being unhappy that they did not receive this reward in the past). So your most loyal clients start to be at risk. This behaviour is also likely to stimulate your competitors to react – and that can only trigger a race to the bottom on fees. If every client paid 50% of ‘normal fee levels’ in the example above, then income would drop to £100,000 a month, which is £60,000 less than monthly overheads. The special offer forces some clients to effectively subsidise other clients – not a recipe for success. Finally, the partner might actually perceive the outcome as a good result and reach for this tactic again in the future. After all, hasn’t the team’s monthly loss turned into a profit again? However, this is a failure to see the potential impact over time, and what if every partner adopted the same tactic? Are these risks and blind spots enough to stop an individual partner offering special deals when they and their team are not busy? Perhaps not, which is why effective control of pricing is needed at both departmental and firm level; quite simply, pricing decisions should not be left exclusively to the individual client-facing partner. We will look at that in more detail below.

A much better approach is to take people out of the underutilised team and transfer them to busier parts of the firm or send them to work inside a client for a period for free or at low cost. That’s an investment in building relationships and goodwill in a way that does not violate your pricing policies.

THE RATE CARD

If I were to walk into a car showroom and approach a salesperson to enquire about the price of a particular car, I would be surprised if I found out that the price quoted to me depended upon which salesperson I had asked. The complexity of services pricing is not just because the scope of work is often uncertain (just like the specification and cost of fitting a new kitchen in a given property could vary immensely), but because even the price of individual workers in the firm is usually very flexible, and no two people will necessarily perform the service in the same way. Seemingly identical partners or associates will be charged at different rates to very similar clients. The typical situation where you are charging for time spent (not on a fixed fee) is too flexible and uncertain, too open to individual negotiation.

In one firm where I was working, the partners discovered that clients had started shopping around within that firm because the clients had discovered that if they rang three different partners and asked for a quote, they would receive three very different figures!

The foundation of good pricing is that it must be fair and equitable. Fairness is about not taking advantage of clients and always being able to explain and justify your prices openly. Equitability is about ensuring that similar clients are paying similar prices for similar services. If you want to understand the importance of this, imagine that a hacker gained access to your systems and sent every client a list of the prices being charged to all your other clients. Would that be OK?

Imagining this worst-case scenario can be useful in persuading partners that you need to pay attention to your baseline pricing (this is your rate card), to your discounting policy and to your approach to deals that fall outside one or both of these (for example, when signing multi-year service agreements).

In constructing your rate card you need to stand in your clients’ shoes and consider the value that they receive from the individuals that will be delivering the service, particularly because firms are surprisingly egalitarian when it comes to individual rates. This means that some firms set rates according to grade/level (e.g. partner or manager) without differentiating by depth of expertise. This is a very simple error. It almost goes without saying that most clients would prefer a partner with 20 years’ experience to another with two years’. Giving both these people the same price leads to overwork at the senior end and a younger partner struggling to establish their practice. Similarly, the shape of the pyramid underneath a partner, the extent to which they are able to leverage their team with more junior staff who are also able to charge for their time, is also an indicator of the required hourly rate. A true Rocket Scientist may have only one or two other people in their team and that requires that they all charge at hourly rates that are higher to reflect their specialism and expertise, while those carrying out Relationship Advice with much larger teams would justify lower rates.

After taking these factors into account you are then able to create a list of rates for each level of fee earner in the business. These rates need to be informed, but not set, by your costs. Remember that cost-plus pricing is suboptimal, but will enable you to set minimum rates that deliver a minimum level of profitability. The actual rates will also be affected by your current rates of charge (what clients believe is the ‘going rate’), what your key competitors are charging and your business strategy (type of work, type of client, rate of growth, perception of the brand and so on).

Now to the key issue. Having set your rate card, do you allow discounts from it, by whom and by how much? You need to take great care that you do not end up creating a discount policy as opposed to a pricing policy. Let me explain the difference. It is very common for organisations to have a rate card and then to have layers of discounts that can be provided to clients which require increasing levels of sign-off. So, the front-line salesperson may have the right to give up to 10%, a divisional head can add another 5%, a regional director another 5% or 10% and so on. Add to this structure a sales incentive (often through the chain) that rewards income rather than profit, and the way ahead is clear. Clients will be offered whatever it takes to seal the deal, safe in the knowledge that there is simply an administrative process that will (in most cases) rubber-stamp the deal. Such discount structures are particularly generous when they meet strong-arm, heavily procured purchasing procedures. A soft process meets a tough one and there is no doubt who wins.

A pricing policy, on the other hand, allows for discounts but those discounts need to be justifiable incentives for desired client behaviours. That is the difference – they are incentives, not price cuts. The front-line partner should have an ability to give a discount up to a certain amount, but only against agreed parameters, and after receiving something valuable in return. For example, a maximum of 10% might be allowable against factors such as a minimum annual level of spend, a commitment to (sole sourced) future projects, flexibility on the speed of response. You can also assume that, being on the front line, these pricing defences will be relatively weak and that in very many cases, for one ‘good’ reason or another, the 10% discount will be given. Your rate card needs to be built upon that assumption (to spell this out, the rate card must start at prices which assume 10% will definitely be given away).

After that 10% any greater discount needs to be thoroughly justified – so that a value engineering exercise is carried out on the basis that a changed price would mean a changed specification. In other words, discounts above the discretionary 10% need to be reflected in changes to what is going to be delivered. If the argument is around hourly rates then you need to hold the line. Negotiations should be around, ‘I can’t get you more than 10% off the rates, but if you spend more than £250,000 then I could look at some added value’, rather than, ‘I will have to get my regional manager to sign off the discount of 15%’. If you find this difficult, then I recommend some professional training in negotiation skills as we all tend to be rather weak when negotiating on our own behalf, as opposed to a client’s.

WRITE-OFFS

There can be many reasons why you need to write off time or work on a matter. You may have agreed a fixed fee but carried out more work than budgeted; you might have given a project-based fee and some elements of the work took longer or involved more people than anticipated; you might have decided that you cannot charge some work to a client because (even to you) it looks superfluous or excessive in scope. Given that the key management systems of firms tend to rely upon tracking activity levels and (very often) recorded time, there have to be controls in place to prevent people simply being able to write off time or money after the event (or worse, understate time during the event), or your accounting systems will not stand up to audit. Profits can prove to be illusory or overstated.

It may come as some surprise that the typical controls are often paper-thin in that they may require a sign-off from other partners, but those same partners are more than happy to countersign these because they will require the same treatment on their own write-offs. So a culture grows where partners soon learn who will sign write-offs without raising too many questions, and are then happy to return that favour. Better controls are needed, in the first instance to challenge the write-offs and test if these can be negotiated with the client, but also so that the firm can learn from its overruns and partners feel under a real obligation to avoid them if possible. Partners need to learn the skills of accurate quoting, scoping (and re-scoping when needed) and efficient delivery, and they won’t do that if they can just ‘carry on as normal’ and write off their mistakes.

When I am consulting into firms, one solution I often suggest is for the firm’s finance team (separate from the partners) to circulate their top 10 write-offs each month, showing the amount written off, the partner requesting the write-off and the name of the partner who signed it off. Peer pressure does the rest.

ANALYSIS OF CURRENT CLIENTS

Entire volumes have been written about the financial aspects of service businesses, but I have found two relatively simple tools that can help to prioritise action and identify individual strategies for each major client. Before using them there is a very simple listing that you can create that will make you think hard about which are your most valuable clients.

That is, to take your top 100 clients (or whatever number is relevant for your business) and create two lists. In the first list you rank them, in the very typical fashion, by turnover. Next to this you create a list of the same clients but ordered by profit: i.e. the client that earns you the most profit is number one, rather than the one that has the largest turnover. Every time I have seen this done, the lists are very different and it will make you realise that it is the clients who top the profit list that are the really valuable ones for your business.

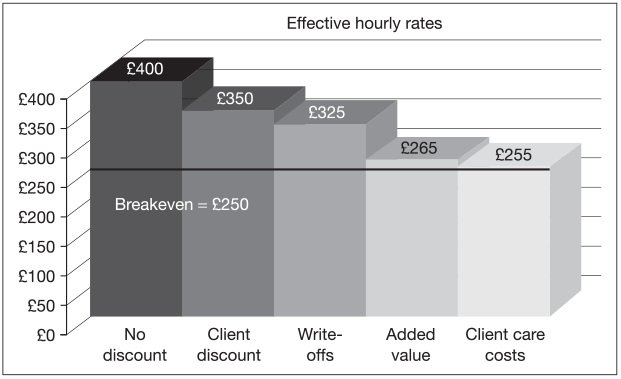

Let’s now look at two analytical tools that can be used with pretty much any service business. The first of these is called a waterfall diagram, and shows the different steps (down) that have taken place from your full rate card price to the actual payment rate you receive. The example in Figure 11.2 illustrates how simple and effective this can be. It needs to be conducted on a client-by-client basis (and may run across reporting periods) to get an accurate picture.

This example uses a rate card rate of £400 for a partner, and then a cost-plus calculation to show the breakeven point of £250 an hour. The waterfall shows that:

- Against a starting rate per hour of £400, the client has been given a £50 discount (12.5%) so that the client has a contractual rate of £350 an hour.

- Looking back over (for example) the last 12 months of bills, the average write-off on bills (irrecoverable recorded time) equates to another discount of £25. You would calculate this by seeing the total value of write-offs and then converting that by averaging its cost across the total of hours worked.

- Next, calculate the total cost to you of all the added value (e.g. uncharged work, benefits in kind and the like) given to the client and average that over the recorded hours which, in this example, creates another discount of £60 an hour.

- Finally there are client care costs – this could be the cost of regular review meetings with the client, entertaining, preparing and analysing performance data and so on. In this example that equates to an average discount of £10 per hour. For simplicity the example is using chargeable rates for this time on that the assumption the partner could have served another client.

- The end result of all of these steps in the waterfall is that the effective recovered rate from this client is £255 an hour, only marginally above the breakeven point.

Figure 11.2 Waterfall diagram

You need to examine your own business to work out what the actual stages are in your business’ waterfall, and then take your largest clients and perform this analysis to create a unique waterfall for each client. The main purpose is for you to work out what actions would have the greatest impact on the profitability of that client. In the example above there are two major areas of concern: the initial discount looks high at 12.5% and the added value is clearly a real issue here, knocking an effective £60 an hour from the effective rate. So you need to concentrate your efforts there. It’s a simple and very visual way of identifying the right strategy on a client-by-client basis.

Figure 11.3 Pricing scattergram

The second analysis is a scattergram and it shows which clients have good deals and which have poor deals on fees. It compares their average rates and the volume of business they conduct with you against similar clients. Here we accept the normal business assumption that larger clients will expect to be on better (lower) rates than small clients, and it works irrespective of whether you are charging by time taken or on fixed fees. In the example shown in Figure 11.3 I have used average hourly rates of charge and compared that with annual spend for a selection of similar clients (such as by type of work or geographies served). The line shows the gentle slope that you would expect (and so would the client) that the more they spend, the better average rate they would be given.

In the scattergram, the line shows the anticipated drop in average hourly rate as volume of business increases across the x-axis on the bottom line – dropping from £350 an hour to say £300 an hour from minimal spend to £3 million. What this reveals in the highlighted area on the left is a group of clients that have a low annual spend and a low average rate. This is a relatively easy starting point. These clients need to have it explained that they need to pay an increased rate of charge or they need to deliver a lot more business. They are enjoying lower rates than much larger clients.

On the right you can see a group of large clients paying rates that are above the expected level. The task here is to deliver real added value to these clients (rather than simply dropping the rates) so that you can show that they are receiving fair value for money. This is your protection against these clients being approached by a competitor who offers them a lower rate (closer to or below the line), because you are then able to respond to show that the competitor may be offering lower rates, but without all of the added value which you provide. That may, of itself, end the matter but if not, the line provides a guide for reducing the price against a reduction in the added value that you are providing.

In this section I have briefly looked at the fundamental control issues that should be useful to any service firm. Without these in place, it is not possible or realistic to excel at pricing.

Now it’s time to turn to this final topic. How does a firm look beyond controls and seek to achieve competitive advantage from its pricing capability? I am greatly indebted to Robert Browne for writing the following section. Robert has over 20 years’ experience helping companies around the world develop and execute pricing and sales strategies that drive growth. He is a partner in KPMG and leads their pricing practice in the United Kingdom.

BUILDING PRICING CAPABILITIES BY ROBERT BROWNE

Let’s start with an important lesson from many years working with service firms. What we find is that most think about pricing as a tactical lever to drive sales: if you lower prices, your win rate and volume will increase, and if you increase prices it will have the opposite effect. In practice, more often than not, these firms set their prices based on cost plus a margin or relative to perceived competitor prices. Most of the firms we encounter have not invested in pricing as a strategic capability and have not developed and embedded pricing policies, processes, roles or training. In contrast, purchasing departments have made vast improvements in capabilities over the last two decades and have been very successful in driving prices and margins lower in many service categories. A recent conversation with a chief purchasing officer from a large European bank drove this point home (what he said is echoed by other purchasing professionals): service firms and particularly professional service firms, are easy targets for purchasing departments. They are typically not well prepared or disciplined in price negotiations and, given the fixed nature of their cost base (the marginal pricing problem), are quick to give up price and margin to secure sales.

In the absence of strong pricing capabilities, a number of service sectors have been (or are) in the process of driving down long-term profitability either quickly through ‘price wars’ or a slow, gradual decline in prices through over-discounting or added value (i.e. adding valuable features or performing services without changing prices). As prices and margins slide, it’s unsurprising we now hear more and more executives and managing partners of firms talk about their need to protect or improve pricing. Easy to say but hard to do of course, particularly when we look inside these organisations and see little or no pricing capability.

THE ROLE OF PRICING IN THE ORGANISATION

The first step for any firm is to make the decision to build a pricing capability: this must be visibly and consistently sponsored by executive management. The second step is then to define the role of pricing in the organisation, and we believe this must be completed before deciding what the pricing organisation will actually look like or be responsible for. We believe this sequence is necessary, simply because we have seen a lot of pricing organisations become marginalised and ineffective because their role was not defined clearly in the first place, and they defaulted to roles others didn’t want to play or for which they did not have resources. We see the role of pricing defined by two dimensions: the role in pricing decisions and the role in pricing processes. The combination of these two dimensions produces four distinct roles (see Figure 11.4) and it’s critically important to choose one role only and build the pricing capability around this purpose, recognising that the role may evolve over time. Naturally, the service sector (its maturity, competitiveness, growth, etc.) and business type (size, client mix, offer range, etc.) matter a lot. Businesses with large and complex contracts are likely to want pricing to lead the bid management process. Businesses with a high frequency of transactions will want pricing to set guidelines, or rules for tactical execution of pricing decisions. Businesses with new or fast-changing offers may want expert pricing resources to advise as and when needed. Businesses with frequent, complex transactions will require pricing to play leading roles on both dimensions. While appealing in some ways, we would advise most firms not to start with Commercial Partnership as their pricing purpose if they have little or no capability today. We had this experience recently with a client providing services to the telecom sector. They wisely defined the pricing role as Functional Coordination first, with an ambition to migrate to a Commercial Partnership role over time. Our experience with successful pricing organisations is that they typically started with one of the other three roles and evolved it over time.

Figure 11.4 Role of pricing in the organisation

DEFINING PRICING CAPABILITY

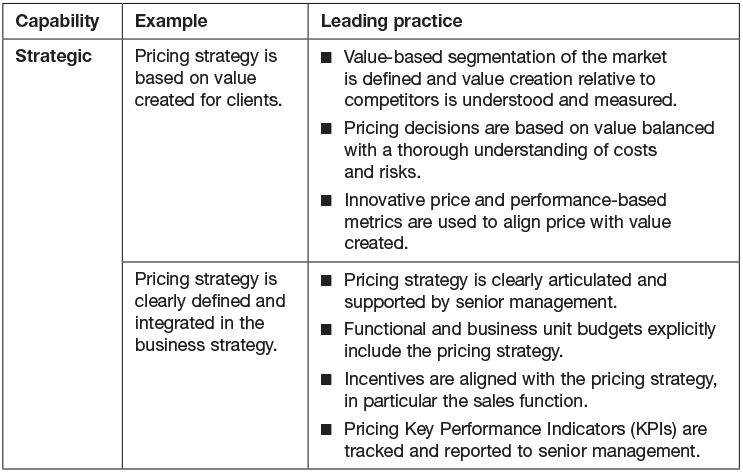

Once the role of pricing has been agreed, the next step is to define and develop an effective pricing capability. There are three overall elements to the pricing capability – Strategic, Tactical and Supporting (see Figure 11.5) – and within each there are distinct capabilities and a range of phases of maturity. Among the best firms we have worked with, their strategic, tactical and supporting capabilities are aligned and drive pricing decisions that are integrated with the overall business strategy.

At the strategic level, pricing decisions should be based on an understanding of value created for clients, as well as the cost and risk to provide the service (pricing should be set based on value, but with cost plus target margin as an important sense-check). Examples of strategic pricing decisions include the definition of the offer (services, bundles, solutions and so on), segmentation of clients (offer and price structure by segment), price model (fixed fee, performance-based fees, subscription-based fees and so on), but also how pricing changes over time (to account for changes in costs and demand). These strategic pricing decisions must be clearly articulated and understood across the business, and executive management must commit to the strategy and walk away from work that does not fit with it. To illustrate, we spent time with the CEO of a printing service to move him away from a volume-based pricing strategy (his declared ambition to ‘fill the machines’) to a value-based pricing strategy that reflected the value of their higher quality service and flexibility, as well as the effect of seasonal changes in demand.

Figure 11.5 Pricing skills pyramid

At the tactical level, the price and discount policy must align with the pricing strategy, and pricing processes and controls around the policy need to be clearly defined. Perhaps most importantly, how pricing decisions (particularly the difficult ones) will be made should be clearly articulated and relevant responsibilities assigned. We are no longer surprised when we see firms make pricing decisions at the last minute, in the final days leading up to the pitch or possibly in the taxi on the way to the client. While intuition and experience will always play a role in pricing decisions, the best-performing firms we have worked with use data and analysis far more than intuition in pricing decisions. For example, a client of ours that provides scientific testing services was faced with a difficult price negotiation with their largest client. To prepare for this negotiation, the management team created a data pack (the history of past prices paid by the client benchmarked against other large clients, analysis of the client’s realistic alternative sources of testing and so on), and a range of price negotiation options with supporting financial models. Having clear, data-driven pricing processes and controls allows pricing decisions to be made consistently and effectively. It also creates a disciplined and proactive approach that helps an organisation move away from being reactive (typically with insufficient time or data) to competitor and client tactics.

Finally, it is the supporting capabilities – the right pricing organisation, skills, data and tools – that drive and sustain successful pricing strategies and tactics. As mentioned earlier, we find that most firms have not developed the supporting capabilities that will deliver consistent, high-quality pricing decisions.

In the table below, we give examples of pricing capabilities from our work with clients and an indication of what leading practice for these capabilities would represent.

Leading capabilities cannot be created overnight, and for most businesses this list will represent a substantial shift in capabilities and mind set. Successful businesses that have developed leading pricing capabilities have taken a phased approach. Once there is alignment on the role of pricing in the organisation, their first step is to get clarity and consensus on the target capabilities required for executing this role. The second step is then to assess and agree on the gap between existing capabilities, and the final step is to define the action plan and responsibilities for delivering the changes required.

Not all capabilities can or should be addressed at the same time. We recently worked with the pricing function for a client and helped them to identify and describe each of the individual capabilities they wanted to build, and then rank them against two dimensions. The first dimension – ‘Enabling’ – allowed them to evaluate the degree to which each capability supports other functions in the organisation; and the second – ‘Impact’ – measured the degree to which each capability will put them on the path to top quartile performance in their industry. This helped the client to develop a priority shortlist of capabilities and develop an action plan for each. Over time, other capabilities can be added and existing capabilities can be reviewed and refreshed.

PRICING NEEDS A HOME

In small firms, the owner or managing partner will be heavily involved in and responsible for pricing decisions, and we believe this is a good use of their time. However, in large and more complex organisations, it is likely that many functions will want to play a role in pricing. This is where problems can start: not only does everyone want to be involved in key pricing decisions, but most people feel entitled to or simply have worked in the business long enough to ‘have their say’. The issue is that ownership for pricing is not clearly articulated in most service firms, and this can produce lengthy ‘internal negotiations’ as well as bad pricing outcomes.

There are two information challenges, one internal and one external, at the heart of the ownership issue. Looking internally first, sales partners and associates will claim they should own pricing because they are closest to the client and competitors, and have the best insight on what is a competitive price in the market. Operations, on the other hand, are able to look across the business (for example at utilisation levels) and know when capacity is more or less valuable. Finally, finance will have the best understanding of the cost base and the impact that pricing decisions (particularly poor ones) have on profitability. The challenge is that all three have a role to play, but none have all the information needed to make the best pricing decisions. The second, external, challenge relates to clients and competitors. In terms of clients, what we want to know is how (and ideally how much) they value our services and solutions compared to competitors, which will help our understanding of their willingness to pay. In terms of competitors, we would like to know how they will price when we compete against them.

Given the complexity of these two challenges but also the critical impact that pricing has on sales and margins, we believe every firm should have a pricing organisation. This may be just one individual or a full pricing team, but every firm needs one, and if we accept the need for a pricing organisation, three questions arise: what should it be responsible for, where should it report in the organisation, and how should it be structured?

What should the pricing organisation be responsible for?

The answer to this question will be defined for the most part by the role of pricing in the organisation. Along the two dimensions (pricing processes and pricing decisions), there is a continuum of responsibility which we have already discussed above. For example, the scientific testing services client mentioned earlier has recently created a two-person pricing team with responsibility for working with locations to define their pricing plan for the next financial year, and then measuring their performance against plan. Another area of responsibility for the pricing organisation should be managing relevant pricing data and tools. Most firms have more data than they know what to do with, and this is acute in the case of pricing. Historical transaction and win–loss data are often a treasure trove for the pricing team to analyse pricing trends and consistency by client and by salesperson. Simple analysis of past pricing decisions can illuminate poor pricing controls, and sources of value leakage and more sophisticated price sensitivity analysis can identify opportunities to increase or decrease prices to drive sales. However, the truth is that most firms today don’t actually know how price sensitive or insensitive their clients are, and as a consequence are far more likely to reduce – or at best maintain – prices and shy away from any thoughts of price increases.

Developing and maintaining pricing tools and systems should be assigned to the pricing organisation. Almost every firm will have some form of pricing tool, and these vary from spreadsheets to sophisticated software. The nature of one’s business (high versus low transaction volume; complex versus standard solutions) will determine the tools or system requirements, but the accuracy, effectiveness and consistent use of these tools is critical to good pricing decisions. Recently we worked with a data services client to build a new quoting tool that embedded a revised rate card and new rules about discounting and escalating price decisions for approval, and this is what we expect pricing organisations should be capable of delivering. However, there are some limits to the use of tools and we would caution against ‘black box’ pricing tools or pricing organisations defaulting to be a ‘modelling team’ for pricing decisions. We have seen many pricing tools end up on the scrap heap because they have either become too complex, or no longer reflect the reality of prices in the market.

A further area of responsibility for the pricing organisation should be reviewing and reporting on pricing performance. We have found that good pricing metrics have been overlooked by most firms. There are a few simple metrics which can be highly effective in driving better pricing outcomes (such as adherence to pricing policy, number of pricing decisions escalated and turnaround time for pricing decisions); but there are also some more complex metrics that start to get at the question of whether one’s prices are successful in the market (for example, when sales growth is separated into price-driven and volume-driven growth). We have also found that most firms do not put adequate effort into defining the role of pricing in the budgeting cycle. We see a lot of firms make simple, inflation-driven price assumptions for next year’s budget, whereas a more accurate and action-based approach (so that results can be tied back to actions) can be a key responsibility of the pricing organisation. This is exactly what our testing services client implemented for their most recent budget, and not surprisingly what is agreed in the budget must be delivered and attracts the attention it deserves. The client used past transaction data to assess the level of pricing performance (e.g. list price adherence), identified and quantified a number of areas for improvement and used this information to set a price uplift target in the budget. They defined a set of metrics to monitor the execution and reported progress to the senior management team on a quarterly basis.

A final area of responsibility for the pricing team, but perhaps the most important of all, should be to help the organisation to define its pricing strategy. This may be by practice or service line or by location, but every firm needs to have a clear pricing strategy and it needs to be understood and executed by every function.

Where should pricing report in the organisation?

Among the firms that have a pricing capability, there is a surprising amount of variation in the answer to this question. We recently conducted a benchmarking study of pricing capabilities for a client and found that each of the five firms we reviewed had pricing reporting to different functions. Typically, however, most pricing organisations report to either sales and marketing or finance, and there are arguments for and against both. On a few occasions, we have seen pricing report to operations or strategy, and we have yet to find a firm where the pricing organisation is a stand-alone function with a chief pricing officer and a seat among the executive team. The debate over where pricing reports is based on three key criteria: insights, incentives and independence. It’s not surprising that the rationale for locating pricing in sales is to keep it close to insights and reality around clients and competitors, and there is a lot of merit to this argument. On the other hand, the incentives in the sales organisation are typically weighted towards sales volumes or income, and hence prices and margins are often sacrificed to drive sales.

The rationale for locating pricing in the finance function is usually because their incentive is to see both sales and profits grow, and they are independent of sales (who want to drive volumes and serve clients better) and operations (who want to keep costs down and increase delivery effectiveness). However, finance will always lack the client and market insights required for pricing decisions. Locating pricing in finance is often a convenient match of capabilities (access to data, analytical skills), but our experience is that it works only if the processes and decision authority are very clearly established and the pricing organisation is a true commercial partner to the sales team. One of our clients has made this work. The pricing team (sitting in finance) run the bid management process and they also have veto rights to stop deals that are below an agreed profit threshold. However, what doesn’t work is when finance acts as a gate keeper for pricing decisions or becomes a modelling resource for the sales team without a role in pricing decisions. We have seen most success when pricing is a stand-alone function reporting to the Profit and Loss owner (e.g. managing partner for small firms or practice leader or Chief Operating Officer for large firms). Moving pricing away from the exclusive domain of the front-line sales team creates the necessary independence to avoid marginal pricing and, when it works well, the pricing team can provide support and coaching to the selling partners, particularly when dealing with high-stakes negotiations.

How should the pricing organisation be structured?

Interestingly, this is also a question with many answers in practice. The spectrum of options is based on two dimensions – the level of centralisation and the level of collaboration – and the choice of structure will be determined by the business type, size or culture (complexity of business, speed of pricing decisions required, volume of transactions, regional, national or global clients and so on). We have identified four organisation archetypes (see Figure 11.6) while obviously recognising that there are many hybrid versions possible. The centre of scale option is typical for organisations with a high volume of standard products and services, such as a quoting or trading desk. The centre of excellence is more typical for firms that have fewer but more complex transactions where the pricing team can get involved in all aspects of the deal, including preparing for rounds of negotiation, or firms that have high volumes but have decided to deploy light-touch pricing support in the form of pricing ‘fly-in’ support or a pricing helpdesk (similar to what both our data services and testing services clients employ). The remaining two archetypes are more typical for larger, and more decentralised, firms that operate many business units across many sectors and markets. They are similar in that pricing resources are local to pricing decisions and can therefore provide support quickly when needed. These two archetypes differ only in that the networked support model creates a virtual pricing community across the entire firm to share training, tools, best practices and experience. Typically the networked model is a superior approach, but does create additional cost in terms of maintaining a community across the firm, and works best when sharing best practice is relevant from one part of the firm to another. We have seen clients where the business units are so different that the potential for learning is limited. However, one of the challenges with pricing resources dedicated in business units or markets is whether they can maintain the overall pricing role. We have seen clients where one pricing person in each market gets isolated and becomes an analytical research resource for the local management team.

Figure 11.6 Pricing organisation archetypes

A successful hybrid model we have seen at another data services client is a mix of centre of excellence and networked support. They have a global centre of excellence reporting to strategy in the corporate centre as well as dedicated pricing resources in their key business units. The centre of excellence performs and guides ‘special projects’ where required as well as guiding local projects and sharing best practice. There are no hard rules as to which archetype fits any given firm, but the business type, size and culture as well as the nature and volume of the pricing decisions will determine what is most appropriate.

Two further considerations for the pricing organisation will be the size of the team and the seniority of the sponsorship. The team size will be a factor of the volume of deals and complexity of pricing decisions and, to a degree, the speed of pricing decisions required (although speed can be managed by better pricing tools). We have seen a number of clients separating their pricing roles into ‘bespoke pricing’, where individual deals are priced and negotiated, and ‘standard pricing’, where standardised products and services are priced and promoted and updated periodically. The data, tools and time frames for pricing decisions vary considerably between ‘bespoke’ and ‘standard’ pricing decision support. The second consideration, senior sponsorship for pricing, is critical to sustaining pricing capabilities over time and delivering the benefits. Without senior sponsorship, pricing processes and decisions can get ‘stuck’ and once that starts to happen, the perception of pricing’s role and effectiveness can be negatively affected. We strongly believe that a sponsor for pricing on the senior management team is a key success factor for pricing capabilities. This could be the head of sales or finance director or, better still, the managing partner. In our experience, we only see firms with senior sponsorship for pricing as ‘price leaders’ and realising the most benefits from effective pricing.

SUMMARY

Firms that are world-class in pricing focus on three key areas. First, they invest in understanding value. They analyse and quantify how their services create value for clients compared to competitors, and this requires that they have a detailed understanding of where and how value is created from the client’s perspective, by segment, to inform better propositions and pricing decisions. Second, they leverage relevant and timely data to inform decision making. For example, most have access to accurate profitability by client and service. Analysing past transaction data for consistency is critical and analysing price sensitivity data can be invaluable. However, what pricing leaders all certainly do, is trust pricing analytics to inform pricing over intuition and anecdote. Finally, these firms are investing in and developing their pricing capabilities. We see the leading firms focussed on continuously improving their pricing processes and controls. Clear pricing strategies and policies are standard for pricing leaders, as are effective pricing metrics and Executive sponsorship.