Pricing tactics

Supporting a client in distress

Negotiate with the toughest clients at the right time

Deliver what was actually paid for

Lower rate does not equal less spend

Act for clients that you like (not the bullies)

When I teach pricing on Executive Education courses, I have noticed that the most feverish note-taking occurs once I start talking about the tactical issues surrounding price. People who are having day-to-day conversations with their clients about pricing and money are keen to have instant solutions that they can put into practice immediately the course finishes.

The reality is that, for most partners, conversations about pricing are mainly at the tactical level during their everyday contact with their clients, and this is when speed and good ideas are at a real premium. Tactical solutions certainly have a place, although they are no substitute for a clear business and pricing strategy. I always warn that overreliance on short-term tactics can deflect effort which is better put into strategy formulation and execution. However, subject to that overall warning, I have set out in this chapter a number of useful tactics which I have found to be valuable in the areas of Relationship Advice or Routine Work.

FREE, NOT CHEAP

It can be very tempting to price low on the first deal with a new client, or for a new area of work with an existing client, with the view that this will lead to a long and profitable relationship. While great in theory, in practice this is a bad tactical move. Entering into a new relationship with a heavily discounted price can position you as a low-cost provider and is a recipe for an unpleasant surprise when you try to charge your normal rates later. For example, let’s say that you are approached by client and you assess after scoping that the particular piece of work will cost £25,740. It is a mistake simply to offer to do it for £15,000. The next time that they have a similar job they will be anticipating a fee of only £15,000, and it would be a shock if you then proceed to charge the normal rate of £25,740. You won the work under false pretences. The same applies when quoting hourly rates – don’t start low under the illusion that you can increase rates later. This almost never happens; if anything, subsequent negotiations bring the rates lower still.

It is much better to find a piece of work you are prepared to do for free. Call it a gift; and the size of the gift will depend upon the size of the potential prize that is available from this client, because then the client is under no illusion that the next job will not be at the same price. The aim of this approach is to have the client understand that this gift is your initial investment in the relationship.

There are alternatives around this ‘impressing a new client’ scenario:

- Say that the price is £25,740, but as this is the first time that you have worked on this job you will reduce this to £15,000 as a one-off to show investment in the relationship. That achieves the same effect of making clear that the true price is £25,740.

- If your pricing is a substantial premium above others, then you could put part of it at risk, for example by saying that your fee is £25,740 but that you intend billing £15,000 until they confirm that they are wholly satisfied with what you delivered, in which case you will then, and only then, bill the balance of £10,740.

Whenever possible, I favour the free approach, because it shows a readiness to invest in a future relationship, create goodwill and create an offer that the client finds difficult to turn down (which is important in the very early stages of the relationship).

However, some service firms only have very large projects – for example, they may organise conferences and it would simply cost too much to ‘give one free’. If this is the case, it will be essential to develop taster products such as workshops or training sessions which can be given for free as a way for the client to try them out. It is then important to put a cash value on the free service. For example, state that the normal cost for a workshop would be £5000, but it is being provided free of charge so the client has an opportunity to see you and your service firm in action.

While free services represent real value to the client, they may well cost the service provider absolutely nothing. With an existing business it may be just a matter of the existing team ‘fitting in’ this extra (free) work in the same way that they might spend time on marketing activities or on administration. I have seen major offers being made which were effectively using the time that would otherwise have been spent in marketing to a potential client, so creating a win-win position.

In some cases, during the final stages of negotiation to acquire a new client, discounts are required to complete a deal. I’ve seen partners give away vast percentages of the total profit in order to get the matter across the line. If some form of sweetener is needed then it is important that anything offered is limited in time. For example, it is better to discount all fees in the first three months by 25% while the client settles into your systems (the equivalent of investing in the relationship), rather than reducing the rates of charge by 5%, because that 5% will be lost forever.

SHOW THE PRICE OF ADDED VALUE

We love listing all of the added value services that we provide for free, don’t we? We can become very generous when listing the added value that we will provide to clients because in some sense it doesn’t appear to be real money. However, as we will see when we start analysing client profitability in Chapter 11, the total cost of value-added services can mean the difference between profit and loss.

A useful technique is to put a clear price on added value – for example, to offer to give £10,000 worth of free training rather than to say that there will be three days of free training. Once you start doing this you can see how it starts to add up. An alternative to fairly unlimited and unstructured added value is to create a ‘value-added account’. This is held in your custody, into which a percentage of a client’s spend is deposited for use towards the added-value offerings. For example, you can tell your client that, subject to a minimum spend of £100,000, 2.5% of fees invoiced each year would be credited into a value-added account, which could be drawn down by the client to take free services for them and their team. Clients tend to value this more than a discount or a rebate and it costs less to provide. Apart from placing a clear ceiling on the cost of added value, it also brings in another factor that is useful in any negotiation: if your client is looking to reduce spend then you can in return reduce the amount of added value being given, allowing you to recover some of the lost margin.

GIVE THE CLIENT OPTIONS

There are times when you aren’t able to create a clear project plan and cost, either because of the inability to have a proper scoping conversation or genuine uncertainty about the future path of the work. In those cases the fee that you quote may be rejected out of hand as way too high or too low, simply because it isn’t clear what scale of work the client wants.

In these situations the solution is to make three different offers to the client:

- the first at the top end, which is comprehensive and expensive (gold);

- the second in the middle range (silver);

- a third minimum offer (bronze).

This approach works well because the client will focus on one of these offers and then, after some refinement of the scoping, you can create an agreed project plan and budget.

When I originally started using this tactical solution it was very common for clients to choose the middle, silver, offer and to develop detail around that. However, I have noticed that more recently clients gravitate towards the minimum (bronze) offer, developing a detailed plan around that. This affirms the original concern that if you had produced a single option it might well have been very far away from the client’s expectation, and so lead to an immediate rejection.

DEALING WITH LOWBALLING

Every professional I have ever met has their own horror stories of how they lost a piece of work to a good competitor who came in at a ridiculously low price. To take quite a typical example, if you were to create a PBC quote of £112,000, a good competitor might offer a fixed fee of £60,000. Strangely, I have never met a person who owned up to delivering lowballing quotes, so I do wonder whether some of these have been made up by clients.

However, be they 100% real or not, there is clearly an issue here. How should you respond when you are met with an offer from a good competitor which would be something like half of your quote? There are several effective responses you can use, and none of them involve you dramatically reducing your price or meeting the price of the competitor (this would simply cause a race to the bottom in your marketplace). Quite often it is the client who contacts the partner, wielding the lowball quote and asking for it to be matched. The crucial point to notice in such a case is that the client has called you. If the lowball quote was so obviously the right solution then why doesn’t the client simply accept the quote? The reason is that the client is similarly unconvinced (or specifically wants you to carry out the work), which means that you have some options.

The way to respond to these quotes is as follows:

- Exploit the fact that it’s too good to be true. When the client receives a lowball quote they are pleased to have this in their hands, but also nervous about accepting it. They know this is an unrealistically low quote, and the very fact that they have contacted you is a strong indicator that they would rather you did the work than the other firm and they are just trying to see how you will react to it. In a sense this is a no-lose telephone conversation for the client, who is hoping to use the low quote as leverage against you. If they really wanted to go with the other firm then they would have accepted their quote.

In response you need to explore the quote and their nervousness about it. You should start by saying that there is no way you can match that quote and indeed you doubt that the other firm can do anything like a proper piece of work for that money. The risk for the client is that they may actually get what they pay for, which would be very little senior-level involvement, every corner cut and most likely attempts by the other firm to actually increase the price after they have been instructed. If you are using a PBC quote then you can emphasise that the client can see exactly what is included in your scope of work, and you can be pretty sure that the competitor’s quote is much less clear about the scope of work that will be covered for the quoted fee. After discussing these downsides with the client, you should end by saying that while you obviously cannot match the quote, you could reduce your total fee if you could work with the client on changing the scope. If the lowest fee was most important to them, you can go through the detailed quote line-by-line and see what could be cut out safely. In my experience this often works. - You can argue with the client that the quote they are using against you is not for a fixed fee. It is hazy and unspecific and either will dramatically increase or will be based upon leaving out much of the planned work. At that point the client will be quick to reassure you that the firm has promised a fully fixed fee; in which case I have, in the past, generously offered to send them over a short contract document which ties the opposing firm into the fee being absolutely (and without exception) a fixed fee. This helpful tactic means that the client will either end up with an absolutely fixed fee (and the lowballing firm will have to keep to that unrealistic fee) or, and this has happened in several cases, the other firm will start trying to put in exceptions and assumptions, in which case the client realises that the lowballing quote was not the fixed fee that they had assumed.

- You can’t win them all. There will be cases where the former arguments do not work with the client and they end up taking a much lower quote from a competitor. When you lose business to a lowball quote, the most important thing is that you make an appointment to see the client over a coffee at a time when you estimate the matter will have been completed. You need to know how it worked out for the client. There are essentially only three answers that the client can give you:

- They will say that they received a fantastic piece of work, the firm kept to the quote, they’re very pleased and looking forward to instructing that firm again. I have personally never witnessed this answer, but if it occurs then it’s really important that you understand how and why. If a good competitor has learnt how to deliver a fantastic service at a significantly lower price then you need to know about it, and you need to learn.

- The client will say that they received a terrible service – in effect they got what they paid for. I’ve heard clients say that they couldn’t get hold of the key partner at all and that the team who were supposedly dealing with the work at the firm became severely distracted when another matter came in (generally at a better price). While it was lower cost, it was also low quality. In such a case, your visit reinforces the client’s feeling they should not instruct that firm again, which is good news for you, your firm and your industry. You might also ask the client if they would act as ‘referee’ if another client receives such a lowball quote (i.e. to tell that client what the service from the lowballing competitor was really like).

- The client could say that the price went up considerably (usually to a price similar to or in excess of your price) because the competitor firm kept adding extras or saying things that were essential were out of the original scope and needed to be added. The client feels misled and again, your visit is a good opportunity to make sure they don’t forget this and don’t fall for the same trick again (and may act as a referee).

Lowballing often occurs because a firm can see a gap in its workload and (for the short term at least) rationalises that work at any price is better than no work at all – and actually that is correct in profit terms in the very short term. Lowballing is bad for an industry because it is unsustainable, yet clients quickly become used to lower prices and start to expect them on a permanent basis.

SUPPORTING A CLIENT IN DISTRESS

Sometimes you will be approached by a client who is looking for some sort of special favour from you, typically leveraged off bad market conditions for them or a companywide cost-cutting initiative. It is in the nature of the professional relationship that you sometimes have to take the rough with the smooth and it will be a rare partner who is not receptive to doing something to support a client who has a real need.

However, the worst thing you can do is to lower your hourly rates (which you will use either for charging or for creating PBC quotes), or to lower your fixed fees if the work is repetitive and of a more routine nature. The problem is that once prices are lowered it is almost impossible to increase them again.

In these situations it is important to offer a special deal for a fixed period of time. That could be about rebating a specific percentage of total fees in six months’ or 12 months’ time, or having a temporary discount (shown as such on all invoices) which clearly expires on a particular date without having to have any further conversations. It must be seen to be temporary (because it’s not sustainable without a change in scope) and with a clear end date. You might also seek a swap in return, such as an introduction to another area of work or to a potential new client.

THE ULTIMATUM

What happens if you have been carrying out work for a good client for a number of years and they say that they been approached with an offer of £40,000 and that you either need to match it, or they will have to switch the work? Let’s also assume that the client is telling the truth. By comparison you have been charging them about £50,000 for that particular transaction type.

The worst possible reaction to this is just to match the £40,000. In a very real sense the trust between you and the client has broken down. If you were able to do the work for £40,000 then the client will feel somewhat cheated: you only dropped your price because they found a competitor and threatened you with losing the work. The client just regrets not having done this many years ago.

On the other hand, saying you cannot reduce your price almost forces the client to carry out their threat, otherwise they will be shown to have been bluffing. What is needed is for you to treat this as an opening to negotiation and to explain to the client that while you cannot drop your price to £40,000 for the work you are currently carrying out for them, you are more than happy to sit down with them and look at reducing the price by identifying whether there are different ways of working together that could reduce the amount of work involved. Treat this as an opportunity to see if there is some innovation that could reduce the price, or whether you can reduce the scope of work and therefore the associated price. If you do this, you don’t need to drop to the level of £40,000. Bear in mind that the competitor is an untested service, whereas yours has been provided satisfactorily for many years: linking some price reduction to a reduction in the amount of work involved at your end is a healthy outcome.

PEDESTAL SELLING

It has been well researched that we attach more value to people if we are told of their expertise, even if it is by someone who has a vested interest, such as a colleague of theirs. Here’s an example. I worked with a partner who was a real expert in managing multinational teams. She had been through some headline-grabbing transactions and really understood how to persuade everyone to pull in the same direction and overcome national differences. At first, when a client had an issue with an international team I would say, ‘Let me get Diana to call you, she is great at this stuff’. That’s a nice gift but it failed to communicate the size of benefit they were receiving.

I changed this to:

We actually have a partner who is a real expert at this. She has more experience than anyone I know in how to make international teams and international transactions work. As you can imagine, Diana is in huge demand and is pretty much tied up all the time. However, I did her a favour last month so she owes me one back. How about if I can get her to give you 30 minutes on the phone for free?

Doing this positions you in any future price negotiation for the services of the colleague that you have introduced, because it emphasises the high value they are delivering.

DISCOUNTS FOR VOLUME

We are hardwired to expect that we will receive a discount for volume purchases. However, for many service providers there are not massive economies of scale (except in relation to Routine Work), yet even so a major client will expect to be paying less per hour or per transaction, and this seems realistic and fair.

I have been caught out a number of times by agreeing discounts for clients who claim that they are going to spend £1 million per annum only to find that in fact their spend is massively less. It is crucial that where there are discounts given for volume they are triggered by the actual volumes, rather than predicted ones. You need to agree that the client can have an extra (say 2%) discount if they spend more than £1 million per year, and this is best paid in arrears once that spend has taken place. So, if the client only ever spends £600,000 then they will never see the reduction. Alternatively, if you are forced into giving the discount upfront, you need to have a specific term in your arrangements to say that the rates have been based on a spend of £1 million per year, and if that is not realised then you reserve the right to increase the rates. In practice, that gives you an opportunity to have a good conversation with the client at the half-year if they are falling short of their anticipated spend.

ANNUAL PRICE RISES

Apart from times of severe oversupply, service providers will typically find that their own overheads increase year-on-year because of inflation or increases in pay levels. A firm which agrees one set of prices with the client and does not alter them for three years will see a headline reduction of over 9% based on inflation running at 3% a year. Yet it is not unusual for clients to be on pretty historic rates, with the relationship partners being very reluctant to talk about increasing them.

To avoid this you need to track the rate that the client is paying against the full rate card over time (we will examine the importance of having rate cards in Chapter 11). Let’s take an example of a client who starts with a discount of 10% from the rate card in year one: they are paying £360 an hour against a full rate of £400 an hour. If you don’t increase your rate card then three years later they still have a discount of 10%. However, if you have changed your rate card at least in line with inflation every year (at 3%) then three years later the rate card would have grown from £400 an hour to £437. This means that the rate the client is actually paying of £360 an hour represents a discount of more than 17%. You should be able to have an easier conversation about increasing the client’s rate by pointing out that they now enjoy 17% off the rate card.

In other words, if there is inflation in the economy, your rate card should not stand still even if you’re not able to impose those increases on your clients on an annual basis. You still need to increase the rate card so as to show the actual discount that the client is enjoying is increasing every year.

HAVING LOWER COST OPTIONS

My guest author, Robert Browne of KPMG, says that the problem for many service firms is that they face a highly segmented marketplace but tend to have only one delivery model. In contrast, commercial organisations have become very adept at understanding the different market segments for their services, and then designing something different for them with different price points. We have only to look at the major hotel groups who have numerous very separate brands, and we can see how airlines have developed different services at different prices to target different groups of customers. Even the budget airlines are offering variations that appeal to the business as well as the leisure traveller.

One of the most worrying results of this segmentation failure is that all too often you will find that clients are paying very different prices, yet receiving identical services. The clients are segmented by price, but the service stays the same. For example, one client, who has negotiated particularly hard, is paying £400 an hour for a particular service, whereas a similar client offering similar volumes of work might be paying £500 an hour. What happens if they meet in the bar, or, even worse, if they meet at a conference organised by that firm?

One of the simplest, most effective ways in which an organisation has changed to deal with tough market conditions is the upmarket supermarket group Waitrose. At the start of the last recession, I would have confidently predicted that they would have quite a tough time because they were positioned very much at the luxury end of the market at a time when money was going to be very tight. Everyone could understand how the discount supermarkets could thrive in this environment, but it looked like tough times ahead for Waitrose. In fact, in 2009 they took the opportunity to introduce, alongside their own brand food, a cheaper brand called ‘Waitrose Essentials’. Later that year these accounted for 13% of sales and contributed to growing their market share by 4% in an exceptionally tough market. These were not the same goods; they were lower priced goods that were sourced and designed from the outset to be at a lower price point.

Professionals can become tetchy when asked to produce a lower priced service: I recall one partner given this challenge asking me, ‘Which corner would you like me to cut first?’ In the next chapter we are going to look in detail at how you can create changes in a service allowing several different price points; but for now, at a tactical level, you should have in your armoury a lower specified service which you can offer to clients who are the most price sensitive. This gives them an opportunity to stay with you, even at times when they have to save money, by taking an alternative lower-quality service from you. Of course you have to maintain standards: a useful analogy is to think of a Mercedes A class car, which is considerably less expensive and addresses a different market from their S class, but is still undeniably a Mercedes.

In the next chapter, we will look at the staged approach to creating alternative services. At the tactical level it is important that you have some lower cost options, so that when you detect a client being difficult over the price you have a lower service option to discuss with them. That may be about having different people in the team, having support from another office (particularly one based in a lower cost centre) or limiting senior staff involvement to specific events. Without this, the firm will default to the more typical situation of only having one, very high-quality, service and providing that to all clients, irrespective of the actual price that each client has negotiated.

TEAM STRUCTURE

It’s not just the price that determines profitability, but the composition of the team handling the work. This is self-evident for work which is on a fixed fee – the lower the level of staff that can then be used to complete the work the higher the profit. However, it can also be the case for work charged on an hourly basis. The way in which a team is structured, together with the level of people within the team and also the actual numbers, will have a significant impact on the profitability of a particular deal.

For example, do you have several different levels of people, at different prices, available for clients? I have seen some firms that are adept at systematising the work to enable the right task to be done at the right level. In one case an experienced partner had trained three junior assistants to work with him, giving him the benefit of leverage. This had enabled him to offer a lower partner rate because the work was distributed across a team, whereas a competitor handled all the work at partner level and at a higher rate. This new structure enabled the firm to earn greater profits on a piece of work, even with lower ‘headline rates’. Have you put effort into having apprentices working within your teams?

BE IN THE PACK

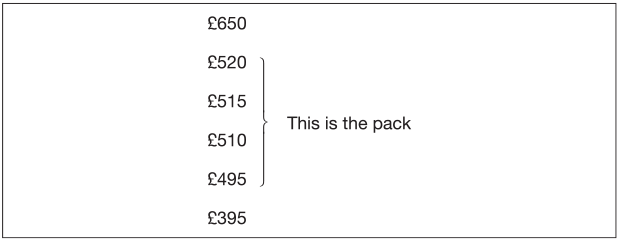

When a client is reviewing fee quotes, whether they’re hourly rates, PBC quotes or fixed fees, they inevitably order them highest to lowest. It’s important that you are ‘in the pack’, unless you have an exceptionally good reason why you are not. Let’s look at hourly rates (the rules are the same for all types of fees) and let’s say that the client receives quotes on an hourly charged basis (Figure 7.1 – only partner rates shown).

Here, the client is likely to discount the firms at the top and the bottom of the scale. At the top end this looks overpriced if there are group of good firms in the middle who are all offering fees of around £130–£155 an hour less. At the bottom end the client starts to question quality and experience if you are £100–£125 an hour lower than your competitors.

The result is that the two extremes can be taken out of the running. Looking then at the pack, they are grouped closely enough together that the typical client would be content with any of them being the chosen firm. With that in mind, you want your quote to place you in the pack but at the top of it, not the bottom. I emphasise this because the normal behaviour of a typical service firm would be for the proposals team to spend quite some time discussing hourly rates in an attempt to be at the bottom of the pack (‘How low can we go on this bid?’), but in fact that lowers the chance of winning rather than increasing it. That’s because the client will try to choose the ‘best firm’ and, if anything, having the highest hourly rates (in the pack) is confirmation of their choice. The client chooses what they think is the best firm and they will not be surprised to see when they examine the hourly rates, their choice is the highest priced. Of course you can expect them to negotiate, and you will know now that you don’t need to move much, but having the highest rates in the pack gives you scope to negotiate and move a little while maintaining a good level of profitability.

Figure 7.1 Grouping of price quotes

Unless you are using a cost leadership – low price strategy (as per Michael Porter) you must use your skill and judgement to formulate a realistic quote that would place you at the top of the pack, not the bottom. How do you find out your competitors rates? That is the topic for the next section.

MARKET INTELLIGENCE

Service firms don’t generally produce public price lists so it can be difficult to know what rates competitors are charging, but having a feel for the pricing landscape of your competitors is useful in terms of your positioning. I have worked with firms where data on competitors’ pricing has really helped their confidence in their own prices, for example: ‘Well if Competitor X is charging £420 an hour then we should have no problem at all with our rate of £450 as we are definitely better than them.’

There are a number of sources for this data and it is worth putting real effort into gathering some of this information so that it will impact on your own pricing decisions. Where can you find this data?

- Debriefs after tender wins and losses. You should have a practice of having a debrief meeting or phone call with a client after the result is known. One of your questions should be: ‘How did our prices compare with the competition?’ I tend to take more notice of the answers when it’s a win, because with losses an easy brush-off (when you actually lost for other reasons) is to say that you lost on price, as this avoids the client having to tell the truth (which might be you were ill-prepared or they just didn’t click with you). The response that I am looking for on a win is that ‘you were more expensive than the others but in the end we thought you were the best for the job’. Anything short of that and I start thinking that we could increase our prices without damaging the win rate.

- Interview people recruited into your firm in the last 12 months who used to work at competitors. This is a much underused resource and you should be meeting and interviewing these recruits as soon as possible after their arrival. Apart from being able to gather real information on prices actually being charged – ‘How does our pricing compare with the pricing at your previous firm?’ – you can also ask what your firm has to learn about its pricing policy from their previous place of work. You might be very surprised by some of the answers. One recent example was a partner who said that he had been surprised that the new firm was charging him out at £60 an hour less than his previous firm to the same clients, and that the budget of required time from him was 300 hours less per year! If you are short of recent recruits then look at capturing this type of information at interview stage. For example, start to ask questions that are useful generally to your business, such as ‘What is your current charge-out rate?’, ‘Does it vary between clients?’, ‘How many hours do you expect to charge each year’, and so on. Collecting this information in an organised way is really useful in helping to shape your own prices. Prices don’t live in a vacuum, but are seen by clients in the context of your competitors’ prices.

TROPHY CLIENTS

A trophy client is there to look good on the biography of the relevant partner. So far, so good. Partners do measure themselves by the quality of the clients that they advise. The problem with the trophy client is that they know that they are trophies and will very often exact very low prices or massive amounts of added value from their advisers (unless they come to you for Rocket Science, in which case you have a level playing field of Rocket Scientist versus trophy client, so the normal pricing rules apply).

Given that it is typically the partner who has very wide discretion over the actual price that the trophy client will pay, it is no surprise that the conflict over price is usually resolved in favour of the client. The partner may also talk about how well this appointment reflects on the firm as a whole and that while this initial deal is at a low price, there can be no doubt that it will lead in the near future to better work at higher rates and other such self-delusional nonsense.

There is nothing wrong with having trophy clients, it’s just very important that you recognise them as such and make them deliver their full trophy client value. In one meeting I had been drafted in as client partner to tackle the problem of a large trophy client delivering a return of just 2%. I started by telling the client that their combination of high discounts, high added value and high partner use had led to an astonishingly low rate of return. The client acknowledged this, but their defence was that their brand was a great one to have on our client list. I agreed, but said that I needed to show some clear value from that if I was going to be able to get my finance director/managing partner/finance committee off my back. As a result I wanted the following, and you should make similar requests:

- a clear written quote about the strength of our relationship that I could use in brochures, online and in proposals;

- an agreement that the client would field three or four calls a year from prospective clients who were looking for a referee;

- an agreement to deliver a speech once a year alongside a partner of mine at a conference.

This was all agreed. After all, we were doing a good job for them and the demands that I made cost nothing, and yet were of real value to me. We also agreed to tone down some of the added value so as to add a few more points to our profit.

Don’t have a trophy client unless they deliver their trophy value. Even then, don’t have too many of them, or your profitability will be noticeably depressed.

NEGOTIATE WITH THE TOUGHEST CLIENTS AT THE RIGHT TIME

This is of most relevance to Routine Work, but I have also seen it have an impact on Relationship Advice. Some clients have become well organised in managing their panels of advisers and negotiate hard at each retender. They typically leverage having a strong brand and also being able to use their high volumes of work to both entice and threaten their service providers. For an incumbent who has a large volume of work, having to tell the firm that they lost the client at a retender (because they refused to reduce prices) is not an enticing thought.

To win at this game, you have to avoid fighting your battles when the client is at their strongest, which is during the tender/retender itself. At that point the client will have all the cards: new firms will be desperate to join the panel (and will be told that they have to be generous on discounts or they will not make it through the first stage), and incumbents will be told that to stay on the panel, a discount of at least, say, 10% is mandatory (ouch).

There are a number of tactics that you need to employ with these types of clients:

- Between tenders you need to work with the client to find ways of being more efficient, reducing the amount of work involved and finding savings. There is going to be great pressure to cut prices at the retender, so you need to be well prepared.

- Capture data on outcomes so that the conversation is not one-dimensional about price. What results are you achieving for the client, across what timescales and how do you compare with the other firms on the panel? Embed a member of your team into the client to gather data. You are going to use this data to defend a higher price at the retender (or at the least to defend no reduction). If you aren’t achieving better results than your competitors on the panel then why should the client pay you more than them?

- Develop other clients and other opportunities. If you become very dependent on a single client then they will have huge power over you, because the loss of their work could have serious consequences for your team and even for the firm itself. Make certain that you spend time in between tenders nurturing new clients and new areas of work.

- Develop ‘extra services’, as described in the next chapter. You may have to accept relatively low prices for your standard level of service, but if you have developed add-on services that cost the client extra then they can be ignored at the retender, but provided and charged for post-tender. For example, you develop an ‘express’ option for when the client asks for the work in under 48 hours, which is at a higher price. The tender is about providing the standard service so you maintain the right to deliver and charge for the express service when requested post-tender.

- Lower the octane rating. If the client insists on continually reducing prices you need to find ways of delegating the work so that the client gets what they pay for. That may mean recruitment and training of more junior staff to take on more aspects of the client’s work. For example, do you have doctors who are carrying out tasks that a well-trained nurse could provide?

- As explained when we looked at the issue of negotiations in relation to Routine Work, timing can be important for Relationship Advice as well. If you aspire to join a panel at the next retender (you are not one of the incumbents) then you are at very real risk of having to drop prices massively, in effect to ‘buy your way onto the panel’. This tends to have the effect of reducing the value of the work for the whole panel and of setting a new pricing floor. I have seen partners who have been involved in several rounds of negotiating and feel so invested in the process (and, of course, having spent so much of their time trying to win the work) that they will offer any price by the end of the process, just so that all of their efforts have not been wasted. That is a really bad place to be. Much better to approach the target client between retenders and offer to carry out £50,000 of work for free, so that they can get to know you and you can start to understand how they like their work done. The worst case for the client is that they just saved £50,000. You use your pilot project to understand what the client wants and to create a desirable and valuable service for them, so that it is the client that ‘pulls’ you in at the next retender. This is a better use of £50,000 of time than fighting over price in a retender, and positions you to fight the next retender on more normal prices and complete with some evidence of what your performance is like.

DIFFERENTIAL PARTNER RATES

The biggest problem of cost-plus pricing is that its focus on internal costs (on your overheads) fails to recognise the realities of the marketplace. So a calculation is made which assigns a certain level of overheads to a partner, then adds the required margin so as to produce an hourly rate for that partner. For example, if a partner is attributed overheads of £350,000 and there is a required profit margin of £100,00 that turns into an hourly rate of £300, if the budget requires 1500 chargeable hours.

One problem is that someone who made partner last year is going to be charged out at the same hourly rate as a partner with more than 25 upwards years’ experience. From the client’s viewpoint the more experienced partner is worth more. Having them at the same rate as a new partner is likely to lead to the senior person being over-utilised, while the younger one struggles to build a professional relationship against what is effectively undercutting by the more senior partner. The rates need to be separated out having regard to what they are worth to clients. An easy solution is for the senior partner to add a premium of 25% and see what happens. Some clients should then switch to the cheaper, more junior partner.

Similarly, some work types allow for higher leverage than others. At the extreme, a Rocket Scientist may work with one or two people in their team, whereas those in Routine Work would expect to manage a very large team (20–50 people, or more). As a result, the actual percentage margins would typically range from 50% for Rocket Science to perhaps 5% for Routine Work, even though both of these partners are bringing in similar returns per partner for the firm. Firms which have this broad spread of partners often struggle to acknowledge these differences. I have seen, for example, partners given a ‘hurdle rate’ (don’t take on work which is less profitable than this) of 20%, even though that makes life extremely easy for the Rocket Scientists (who will most likely start dropping their rates if the target is so low), while those in more mundane work have unrealistically high rates imposed upon them, leading to a loss of competitiveness and unrealistic quotes being sent to clients.

A full service firm is likely to need at least four different rates for partners or managers: one for Rocket Scientists (‘expert rate’), one for seniors partners, one for more junior ones (in Relationship Advice) and one for those who lead highly leveraged teams carrying out Routine Work.

Another problem for cost-plus pricing is that it ignores the laws of supply and demand. If there is huge demand for advice on tax but a huge drop in demand for restructuring, it is a rare firm that recognises this and puts up all prices in tax while removing supply from restructuring (better to do that than to keep supply high and drop the price, because everyone else will be doing the same). There’s typically an easy way to spot these opportunities: look for areas in the firm which are greatly over-utilised and try increasing prices to damp down demand. The people involved in the undersupplied work have the wonderful opportunity of working fewer hours at higher rates and earning more money for the firm.

DELIVER WHAT WAS ACTUALLY PAID FOR

Another tactic for public sector and other heavily procured clients is to make sure that you are delivering only the absolute minimum of what was paid for, and to be astute in looking for and adding on charges for extra services. This is something for which the budget airlines and the hotel sector have become famous. While I consider this to be a very bad tactic for those clients who are paying a fair price (because it will annoy them), it is acceptable for those paying the absolute minimum.

If you want to service the most price-sensitive of clients you need to be very astute in considering what could be extra. A great starting point for that is to create your absolutely basic level of service (your own, plain-labelled ‘value range’) so that you can minimise your costs while maximising the chance that you can sell more expensive extras. If that doesn’t appeal to you, then look at the more strategic issue of whether you want to exit public sector and heavily procured work (or want to pass it to a separately branded subsidiary with a lower cost base).

Too often I see firms struggling to provide the same great service they always did, with exactly the same people, for clients who keep driving the price lower and lower. Better that you keep lowering the scope of what you provide, changing the team structure, using technology or putting the work into a low-cost offshoot.

SHOW THE DISCOUNT

If you are putting in a quote to a major client, or to a new client that you consider will become a major client, then there will be a strong desire to give them a discount from your standard rates. That will also be expected by the client. Let’s say that you have set up a rate card which allows for a discount of 10% for ‘major clients’ (for example, those who should spend £500,000-plus per year either immediately or within a reasonable period of time).

Let’s say that your rate card rates are £500 for a partner, £450 for a senior associate and £400 for an associate. I have seen partners, wanting to be helpful, simply showing that the hourly rates are £450, £405 and £360 respectively. However, the response from the new client is often to demand a 10% discount and refusing to believe you when you claim you already did that. As a result it is important that you set it out as shown in the following table:

| Grade | Standard rate | Global client rate* |

| Partner | £500 | £450 |

| Senior associate | £450 | £405 |

| Associate | £400 | £360 |

*Note: Global client rate is reserved for clients who anticipate an annual spend of £500,000 or more each year. If spend drops below that rate we reserve the right to remove this discount.

LOWER RATE DOES NOT EQUAL LESS SPEND

Whenever you have hourly rates as part of your pricing, even if they are being used to create a PBC quote, often clients will seek to attack the rates and lower them as much as they can. That’s logical, because the lower the hourly rates, the less they will be charged, right? No, that’s actually wrong. I’m indebted to one of my American clients for a story that perfectly illustrates this. He explained that, in response to an order from his CEO to cut costs immediately, he emailed his adviser panel to explain that due to severely adverse trading conditions he would have to reduce all hourly rates by 15% starting the next day, and if any adviser had a problem with that then they needed to come off the panel. All demurred. One year later he asked me, ‘How much do you think I saved?’ I was expecting a boast like ‘One million dollars’, but that’s not what he said. ‘Not a single cent’, was the answer, ‘all the firms just worked 15% slower (or anyway they recorded more hours at the lower rate)’.

This is a useful lesson. If the client’s attack is on the hourly rate, then the first casualty is going to be your ability to give them the best team. It’s easy for you to cave in and reduce rates, but the best professionals in the firm may see these rates and just avoid working for that client. In reality the client is going to end up with the professionals who are least busy, and therefore there is some risk that they will not be the best.

There is also no incentive for professionals to ‘jump to it’ if they think the agreed rates are seriously low. Why not do that work at the end of the day when you are not so fresh?

So if clients become fixated by arguing over hourly rates, it’s worth taking a step back with them and asking them what they are trying to achieve by arguing over them? If it is to downgrade the type of people handling their work, then fine. If it is to reduce spend, then it is much better that you institute a spend reduction project with them and leave the rates alone. We will look at those projects in detail in Chapter 10.

ACT FOR CLIENTS THAT YOU LIKE (NOT THE BULLIES)

Every firm will have clients that they really like, who are paying comparatively high rates of charge, and aggressive, difficult clients who are paying much less but are receiving the same or a better level of service. This happens because we tend to be reactive rather than proactive, and if a client that we want to keep is difficult over money then they tend to get their way (while effectively being subsidised by the ‘nicer’ clients). This is a dangerous practice: how will you explain to the nice clients why they are paying more? The risk is that you lose the nice clients and spend your professional career with the more price-aggressive ones. Don’t do this.

There is a simple exercise that you can carry out in your firm, as discussed previously when it was carried out by an insurance company: segment your clients into ‘like’ and ‘don’t like’ (see Chapter 3). This sounds somewhat unusual, but it often produces very interesting results. It involves taking the largest clients by turnover (top 20, top 50 or whatever is appropriate for your firm) and conducting a survey with the front-line staff in your firm, asking them to rate these clients as ‘like’ or ‘don’t like’. This is a deliberately subjective question about the actual experience of the person in your firm and how they feel about dealing with the client. It is binary – they must choose ‘like’ or ‘don’t like’.

You total up these scores and create a table with just two columns so that your top clients have been divided up. The interesting addition is this: put next to the clients the profit (or loss) made on each individual client and this typically reveals an interesting pattern. If you cannot calculate profitability at a client level in your firm then you could instead list average prices paid by each individual client over the preceding year. You will almost always find that the clients that you don’t like are loss-making or low profit (or low average price if using that measure)! Clients categorised as ‘like’ are much more often the most profitable ones. I started to explain this as ‘We like this client and this client values us’.

It was just as interesting to look at the clients in the ‘don’t like’ column. They were the ones who always had to have everything in a rush, started every conversation by emphasising that the work had to be done as cheaply as possible, argued over the bill, requested a lot of extras for free and generally treated you without respect. In some cases, they were in companies which themselves had a culture of cost-cutting and whose industry profile was to be ‘lowest price’, which meant that they had to keep their overheads to a minimum and so all expenditure was scrutinised and constrained. Some of these difficult clients can just feel like spoilt children who want everything but want to pay very little.

If you find the profit/loss correlation above, then it is worth spending time acquiring new clients that you like and gradually easing yourself out of the others. It may simply be a matter of passing them over to colleagues, as again it has been my experience that when one partner did not have a great relationship with the client, this did not mean that a subsequent partner would have the same experience.

FROM TACTICS TO STRATEGY

Tactics are all very well, but what is the strategic answer? It is to work closely with each client to build a service which genuinely delivers additional value to the particular client and so justifies a higher price, or to develop lower cost and lower priced services to serve clients who have less to spend. This exercise needs to be conducted on an individual basis between clients, but there are certainly common themes that emerge, and the next chapter looks at a much more strategic solution to this issue.