How clients buy services

The key question for this chapter is: ‘What are the criteria that clients use when choosing a service firm for a project or for a panel appointment?’ Once you have a clear understanding of the decision-making process, you will have a better approach towards pricing your services.

My thinking in this area has been shaped by a research project in 2006 which built upon models that I developed when completing my MBA dissertation. By undertaking this research I had hoped to improve my firm’s win rate on proposals for work. The better I understood the way that clients made these decisions, the more successful this task could be. In fact, I was able to produce substantial improvements in win rates, and in doing so I realised I had developed a model that was fundamentally important to the pricing of all services. Then came the recession of 2008 and clients’ focus turned to cost savings and value for money. The result was that the importance of truly aligned pricing came to the fore – it was necessary to use the models developed in order to shape the services provided so that they better met clients’ newly changed needs.

THE DATA

The primary data in my research project involved the analysis of more than 1100 formal pitch results and detailed feedback from clients on 700 of these pitches. I was looking through this data to uncover and understand the reasons clients had given, subjective as they may be, for their decision to appoint or to reject my firm. However, when I started tabulating these reasons it created something of a fog of results. Vague patterns were emerging: there were regular references to price, experience and chemistry (how the client felt about the team that had attended their offices to make a formal presentation). However, it was hard to see any strong correlation. Proposals made to clients who appeared very similar sometimes failed on price, sometimes were successful, with experience being mentioned but no reference to price. In other cases, where everything else seemed to be right, there was a comment on not being impressed with the presentation team. A breakthrough occurred when one of my business analysts aided me by grouping all of the results based upon work types. As I started to refine this, a startlingly strong picture emerged. In the end, I found that the best results came when I divided the work into three categories which I later termed ‘Rocket Science’, ‘Relationship Advice’ and ‘Routine Work’. These three titles will be a constant feature in the rest of this book.

In a sense, there was nothing radical here. Many authors and researchers in services had come up with similar categorisations, for example: ‘Expertise, Experience and Efficiency’. However, what surprised me was to find that whenever I spoke to colleagues in other service firms they, like me, had failed to understand how this division affected the buying decisions of their clients. In particular, it was crucial to understand that we all needed to use quite different language and evidence when seeking to win work from clients in these different categories, and to offer very different pricing options.

After analysing the data and conducting further face-to-face interviews with key clients, I ended up identifying five criteria that clients were using when buying each of these three work types. Using this understanding, I completely redesigned my firm’s proposal process with quite startling results. On the highest value proposals, our win rate moved from 30% to 57% and on average across all proposals it increased from 31% to 49% and stayed there. This wasn’t about clever marketing wording, but simply an improved understanding of the criteria needed to make successful proposals, irrespective of whether it was Rocket Science, Relationship Advice or Routine Work. Importantly, I also gained a much better understanding of whether my firm should actually even attempt proposals on particular pieces of work or panel appointments.

Key point

Using our new understanding of clients’ buying criteria, we lifted the win rate on the highest value proposals from 30% to 57%.

As a first step, it is important to look at my definitions of work types (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Three types of advice

ROCKET SCIENCE

What does ‘Rocket Science’ mean? This is work which is of primary importance to the client either because of its size, its risk or its urgency. Importantly, it is the client that decides whether work is Rocket Science or not.

What are the key features of work that could be called Rocket Science?

- It typically involves a director of the client company. If a director is worried then it is Rocket Science work (and incidentally there will be no issue over the cost).

- The partner involved in the work might be a little arrogant (and I used to joke that much more commonly I would find that they were massively arrogant). This was important. The best analogy that I found was of the truly expert surgeon who had earned a leading reputation in a particular field, one recognised as particularly difficult, with life-and-death decisions being made on a daily basis. These surgeons would often have quite a distant air about them. They might not have a good bedside manner and in fact this different attitude could be comforting to the patient.

One FTSE 100 client that I interviewed described being in the boardroom when a hostile takeover had been launched for the company. She said, ‘Two really arrogant partners arrived from [a major law firm], were quite abrupt but asked exactly the right questions and we felt really safe in their hands’.

In fact, from a client’s point of view, this extreme confidence of the adviser is very reassuring, even though it might be described as arrogant. Rocket Science work, by definition, involves substantial risks or opportunities (or both) for the client and this is a time when an arrogant, ‘I have seen this all before’ attitude is really comforting. They are the Olympians of their specialist subjects. - The outcome of the project might be quite vague. It could be because this involves novel issues or great business uncertainty. Quite often clients may not be able to specify exactly what work is needed and it will be quite open-ended.

- The Rocket Scientists may not be typical ‘relationship’ people. They may be strongly introverted and may not see that client again after the project finishes. Similarly, the client may have no wish to see them again. They will be excited by the intellectual challenge of each piece of work; they will perform at an extraordinarily high level, often working extremely long hours. One of the key pieces of understanding from my research was that where Rocket Science work was involved, the client chose based upon the personal reputation of an individual, not upon the firm’s reputation. The primary criterion for clients when selecting a provider for Rocket Science work is the track record of the individual partner; pretty much everything else will be irrelevant. To continue the example of a surgeon, this will be comparable to a situation where you have been told that you need a difficult and complex operation which carries a serious risk of death. When choosing your surgeon, you need to know the comparative success rates of the alternative practitioners. How many of this surgeon’s patients were still alive five years after the operation? You won’t particularly care about which hospital the surgeon is using or whether or not they are pleasant to deal with. What matters is the end result. What is the individual surgeon’s track record with the exact problem that you had? If they really are ‘the best’, they will be working in a hospital that is fine.

Key point

It was the partner’s individual track record that mattered – it was nothing to do with the firm.

It was interesting to start thinking about how partners known for their Rocket Science work needed to market themselves, something which they almost universally hated doing. How does the client with some Rocket Science work find the right partner? I discovered that there were commonly two decision routes. The first one was through the client’s existing ‘Relationship Partner’ at the firm. So, internal networking by Rocket Science partners was important and easily achieved. The second route was referrals from other clients. To an extent this depended upon the Rocket Scientist having a high enough profile within the business community, but this also could be helped through client partners offering existing clients meetings with Rocket Scientists for free, particularly to give expert talks and presentations (which they enjoyed doing).

It was also worth noticing that, if anything, Rocket Scientists would charge too little for their advice. This came about because the firms where they worked relied upon charging for them by the hour or the day just like everyone else, but that hardly reflected the value which they brought. These experts were the most likely to have a flash of inspiration and solve the client’s problems in an extremely clever way. The best pricing practice that I came across for this area of work, resulting in clients who expressed the highest satisfaction with the price, was to create a safe budget. At the start, the Rocket Scientist talked to the client about the likely total cost. They put themselves on the side of the client by describing the total budget that was needed if the client was going to be safe. For example, a conversation might be: ‘From my previous experience, I can tell you that this project will cost between £1.5 million and £2.5 million. So you are going to need a budget of £2.5 million and we will not exceed that.’ The client was reassured because the worst thing is to create a budget that is too small, so that the client faces the embarrassment of having to request more funds from the board at a later date, which would involve an admission that they had underestimated the cost the first time around.

Once this overall budget had been established the partner would bill regularly, based upon hours worked, in the usual way. However, at the end of the matter the partner would see the client (face-to-face, not on the phone), and would discuss the work that had been done and the outcome that had been achieved for the client. The partner would then agree a final fee. If the results were particularly good, the fee would be at the higher end of the range. If, due to circumstances outside of that partner’s control (not because the partner had failed in some way), the result was not great, then the fee would be at the lower end of the range (or even below it). The partner was seen to win or lose in the same way as the client, and in this way had worked towards ‘value pricing’ – asking for a fee that reflected the value the client considered they had received. In the pricing community, value pricing is considered the highest quality of pricing.

There was something else that was mentioned frequently by clients in this area of work. They were extremely loyal to the Rocket Scientist partner. I would often hear clients say, ‘If that partner left their existing firm then I would follow the partner, I would not stay with the firm’. I didn’t hear this in respect of the partners delivering Relationship Advice (which surprised me) or about Routine Work. This loyalty to the Rocket Scientist partner was understandable. A client who had been through a difficult, important, perhaps risky, situation with a particular partner understood the value that partner brought and would want to use them again if a similar situation arose.

It made me start thinking about the wording I used when talking to clients about particular Rocket Science partners. It was important to emphasise that the particular partner would be committed to the transaction and to promise that they would not take on other work which might cut across that commitment. The client was choosing to instruct my firm solely because of the track record and expertise of a specific partner, and it was important to understand that.

RELATIONSHIP ADVICE

This is the layer of work underneath Rocket Science. It could involve very substantial matters, but they are not seen as life or death and are typically of a repetitive nature. There was one area where I found possible disagreement between partners and clients about whether work was Rocket Science or Relationship Advice. This was where the client had a stream of high-value transactions. The partners handling such work (often correctly categorised as ‘deal junkies’) tended to think of themselves as Rocket Scientists, but for the client this was quite often seen as ‘business as usual’ work and so closer to Relationship Advice. The key features that I identified for Relationship Advice were as follows:

- The stronger the actual relationship the partner established with a client, the more they were able to charge. The trust and depth of understanding of the client’s situation developed its own value: so much so that it was clients who originally described this as ‘relationship’ work. By its nature, Relationship Advice is not typically about ‘one-off’ pieces of work where the client does not expect to see that partner again, but rather about important pieces of work that form part of a continuum.

- Whereas in Rocket Science, clients had been reassured by the steely arrogance of their adviser, in Relationship Advice they were typically seeking a friendly and trustworthy ‘bedside manner’. Clients choose people with whom they can have a pleasant working relationship. Interestingly, I came to the conclusion that clients chose advisers that they liked! This was because they could source Relationship Advice from many firms, so liking (‘chemistry’ was how it was often described) became a crucial differentiator as the core skill that they were buying was available from many firms, and so it cancelled out when the choice came to be made.

- There was much more talk of ‘the team’, and a recognition by the client that the relevant partner would not be involved in every piece of work and certainly would not be delivering all of it personally.

- The client did not focus so much on the individual track record of the partner, recognising that it is a team effort, and so was much more interested in hearing that the firm and the team had relevant experience. This was typically evidenced by the firm acting for other clients that this client would consider to be peers, or in the same division as them. What I found particularly interesting, and reinforced my view that this needed to be called ‘Relationship Advice’, was that clients said only some firms understood that creating a real relationship between the whole team and the client was important. A relationship means going beyond simply delivering the service that is required and actually starting to understand the client’s business, spending time face-to-face with them off the clock, helping them to achieve their business and personal objectives, and helping to train and manage the client’s whole internal team. This truly was the zone of The Trusted Advisor as described in the bestselling book of that name by David H. Maister, Robert Galford and Charles W. Green1. The most successful partners in this zone tend to be more people-focussed and less task-orientated, and displayed a genuine interest in the client’s business rather than just delivering the services. They were less transactional and longer term in their approach. However, just as interestingly, the relationship-building skills which were so important in this area of work were not relevant (even though they may exist) in relation to either Rocket Science or Routine Work.

Key point

Relationship Advice is the zone of The Trusted Advisor, as described in the bestselling book of that title.

ROUTINE WORK

I found little dispute between clients and partners about what could be categorised as Routine Work. It typically arose in volumes, was almost always provided on a fixed fee basis (rather than on the uncertain hourly or daily based charge), and even the choice of external supplier was often delegated quite far down in the organisation. One possible area of contention was that to be truly Routine Work there had to be very low risk if the matter went wrong. It had to be a situation where problems could be resolved with relatively minor financial compensation. There was an inevitable desire by clients to talk of work as ‘routine’ as a method of requiring a lower price. If work was repetitive, but carried a real risk – for example, substantial adverse publicity for the client if something were to go wrong – then there would be grounds for inserting a Relationship Advice level overview of the work to protect against such risks. The typical features of Routine Work were as follows:

- The actual work required, or the end result to be achieved, could be specified in considerable detail.

- Even if the actual cost of carrying out each individual matter might vary, there were sufficiently large numbers for an averaging approach to be taken to produce a single fixed fee.

- There were lots of potential providers and, subject only to a ‘quality hurdle’, the client didn’t really care who carried out this work.

- Price and performance would be under continual pressure, with the service firm expected to produce improvements year on year and to lower prices as well.

- There was very low client loyalty and while clients recognised that some firms did actually deliver a much better service than others (particularly in terms of making the work easy for the client rather than causing them lots of additional administrative tasks), they will still play firms off against each other to achieve, the lowest price that they could, from the best provider available.

At first sight, this might appear somewhat depressing from a price and profit point of view. However, firms that were well set up to handle Routine Work could actually make very high returns with very low partner involvement. The effect of leverage meant that a partner running this type of work could often produce more profit for the firm (per partner) than the best of the Rocket Scientists. Partners involved in this work tended to be good at process and procedure (quite likely the opposite of a Rocket Scientist), and the best of them managed to integrate their processes with those of the clients so as to produce a higher cost of switching for the client. They would also introduce Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), which could be used to generate the data that would justify better prices for better performance.

THE FIVE CRITERIA

Having defined three separate work types, it became possible to analyse the data on wins and losses and to isolate the key criteria that clients used when choosing their service provider, and as a result, to understand the implications for firms in terms of their pricing and their approach to clients’ buying decisions.

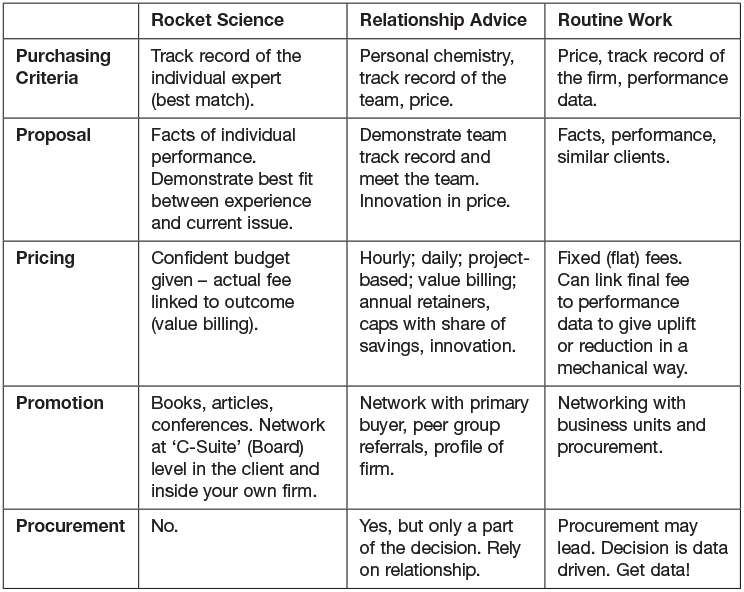

These criteria, which became the ‘5 Ps of Services Pricing’, are as follows:

- Purchasing criteria – how does the client decide which service firm to use?

- Proposal – what evidence does the firm need to produce to convince the client?

- Pricing – what is the best way for the firm to price its services to maximise profit and client satisfaction?

- Promotion – what are the most effective ways that partners can use to market themselves?

- Procurement – what is the role (if any) of procurement and how can the firm best deal with it?

This leads to a grid where the three work types are matched against the 5 Ps of Services Pricing and this is set out below.

For now, I am going to focus on the pricing issues and look at these in turn against each of the three work types. An understanding of how clients use price as part of the buying decision underpins the selection process and forms a foundation for this text.

PRICING ROCKET SCIENCE

Price was not mentioned by clients as one of the criteria when they were choosing their adviser for Rocket Science matters. In addition, satisfaction with pricing for this type of work was found to be high. This seemed to be built upon the principle that nobody staggers into accident and emergency with a heart attack and starts asking the price of the various doctors. But importantly, it also didn’t mean that it was entirely open season on price. Those working at this level in service firms jealously guarded their reputations, and it was important not only that they delivered to a very high standard, but also that the clients did not complain afterwards of having been ‘ripped off’ (although a client describing them as ‘extremely good, but expensive’ was considered something of a badge of honour).

On further investigation I found that the best of these people did not talk about the actual price at the beginning, but rather that they talked about the client needing to put in place a budget that was sufficient for the task in hand. As I mentioned previously, the best partners were seen to be on the side of the client in making sure that an appropriate sum was set aside by way of budget to deal with the issue, so that the client would not be left embarrassed at a later stage by having to ask for considerably more budget.

The best of the conversations contain the following elements:

- The Rocket Scientist referred to previous similar situations (reinforcing their specific expertise in the particular problem or transaction) and gave a range of possible costs. For example, the client might be told that the cost would ‘not be less than £1 million, and could be as high as £2 million’, so it would be sensible for the client to create a budget of £2 million and then the partner would make sure the budget was not exceeded.

- The basis of charging was clearly laid out so the client understood exactly how the ultimate charge would be calculated. In the best cases the partner kept the client up to date on a very regular basis to show how spend was comparing with the stated budget.

- The actual total cost was the subject of a conversation at the end of the project at which the partner talked through what work had been done and in particular, and much more importantly, what had been achieved for the client. Should the outcome not have been fantastic (for reasons unconnected with the skills of the Rocket Scientist partner) then the fee would be reduced so there was an element of ‘sharing in the pain’. Similarly, when a particularly good result had been achieved, a conversation which referred to ‘£1.2 million being on the clock, but in view of the spectacularly good result I propose to invoice £1.5 million’ was seen as both acceptable and appropriate.

Among pricing specialists, the gold standard of pricing is described as ‘value pricing’. Similarly, it is widely accepted that this is extremely difficult to achieve. Value pricing occurs when the seller has been able to maximise their profit by focussing the service around what is most valuable to the client, and the client has been able to maximise their satisfaction, which includes the price paid. Value pricing implicitly accepts that there may be variations up and down depending upon outcomes. In my research, I found that even if the actual time taken had considerably exceeded the budget delivered at the outset, the Rocket Scientist partner was very likely to write off any excess, because to admit the budget had been wrong would reflect badly upon their supposed expertise. Exceptions could occur if a radical alteration had taken place part-way through the matter, which had been well flagged up and a revised budget agreed, but otherwise there was a matter of pride involved in keeping within the originally stated budget.

This also helped to explain why, when a group of partners discuss pricing strategy, some of them will be massively more bullish than the others. It is as if Rocket Scientists are immune to the ups and downs of pricing in the marketplace. When partners have positioned themselves as being in the Rocket Science part of the market, they place considerable pressure upon themselves in terms of the quality of advice and the perfection of delivery. They also understand, importantly, that no amount of price cutting will lead to them winning more work. Clients choose their adviser in Rocket Science situations based entirely upon their personal track record. The better that partner’s track record meets the exact problem that the client is facing, the greater the chance that partner will be chosen. If the partner is not the right person, then cutting their price in half would not alter that at all. There was also a status issue involved. If a partner claimed to be delivering Rocket Science advice then the price (in terms of the quoted hourly rate or daily charge, as opposed to the final bill, which would be discussed) needed to be consistent with that position. It needed to be noticeably above, for example, the rate for a partner who was handling Relationship Advice.

On occasions, I found individual partners trying to impose two different rates upon clients: one rate for Relationship Advice and a higher rate for Rocket Science to reflect the fact that sometimes they were dealing with day-to-day matters, and on other occasions they were dealing with Rocket Science. This was not a successful strategy. Clients judged individual partners and categorised them based upon their experiences with them, and they were not happy for one person to claim two different rates when charging. A Relationship Work partner needs to refer the client to a different partner if Rocket Science work and prices are appropriate. It also seemed that the cost of being a Rocket Scientist was the need to truly specialise and therefore cope with occasional work famines, rather than filling up with lower grade work at lower prices during quiet periods and risk undermining their position.

One fact that leapt out from my research was that there were originally quite a number of cases where my firm had not been successful in a proposal for Rocket Science work, even though we actually had the relevant expertise. To an extent that is inevitable. There will not be only one expert and it is not uncommon for a client to want to talk to two or three potential advisers and then choose the one that is the best fit. If we didn’t have the best fit and another firm (in fact, a specific partner) did, then it was appropriate that we lost. However, what came out of the research project was the realisation that our proposals were quite unfocussed. They would often talk about the expertise of the whole firm, which was actually irrelevant. What is needed is to focus directly upon the issue that the client is facing and then produce quite a simple document which demonstrates the specific expertise of the relevant partner and show how it matches the needs of the client.

What I learnt from this was simple – the need to ask more questions. When asked to propose for Rocket Science work, I needed to understand the problem in considerable detail. This meant sitting down with the client to gain a deeper understanding of the outcome they needed, the challenges they anticipated and how they wanted the project to work. In some cases there was simply a lack of the required expertise, and my firm gained credibility for acknowledging that. In other cases our proposal won because it demonstrated the exact expertise of the relevant partner or partners and showed how their track record matched the client’s needs. The adviser who does the best job of matching track record to needs in this way is the one that is chosen, and quite often at no point has price been discussed at all.

PRICING RELATIONSHIP ADVICE

It is here that my research starts to show clients talking about price as one of the factors in their decision making about which firm to use. Interestingly, it was very rarely the deciding factor. Clients were very clear in saying that the two most important factors were a belief that the firm could handle the work, which is based on their track record on similar work and for similar clients, and personal chemistry with the team that was going to be carrying out the work. Contrast this with partners who often tried to work out what competitors are charging and then go in under that, on the assumption that this would win the work. In fact the client is choosing based upon other factors.

Key point

Price was one factor, but not the most important. Track record and a good cultural fit with the team were considered much more important.

This helped me to understand all of those situations where clients had told us that price was not the most important issue, but then chosen a firm that was lower in price than us. The client’s decision had been focussed very strongly on picking the firm that they thought would be best at doing the work, and would form the best cultural fit with them. If that firm happened to be cheaper than my firm, then so be it. But price was not the decider. As one client put it: If you are not the right firm for us, then you are not the right firm – even at half price.

I was both surprised and greatly encouraged by this finding. All of the partners that I had talked to about this worked upon the assumption that ‘all other things being equal, the lowest price wins’, and this led to a vast amount of time being taken up by partners retelling anecdotal stories of how cheaply direct competitors were selling their services, and how we needed to cut our own prices by more if we were to be successful. This was a deeply ingrained belief. However, the key fallacy was this: in services it is rarely the case that all other things are equal! The clients were directly telling us that they first judged which team of advisers they preferred, and only then did they turn to the issue of price. If it turned out that their preferred team was the lowest price, then (unless it was very low, in which case the client started to doubt that team’s abilities) that was that. If, however, their chosen firm was the highest price (again assuming that they were not off-the-scale expensive), then the client would simply negotiate fee rates with their chosen team. I deal with this scenario in detail in Chapter 3; for now it is just crucial to understand that for Relationship Advice, going in low does not, of itself, increase the chances of success. What it does create is an inability to price yourselves at a higher, more reasonable rate at a future point – why, when they were offered Rate C for you, should they then pay Rate A for the same partners a short while later? Pricing low positions you and it is very difficult to reposition at a higher rate later on.

Firms need to change their approach to winning Relationship Advice to match this finding. You can massively increase your chances of success if you meet several people from the client side, so that you gain a much better understanding both of what the client is looking for in terms of the work (which would help you to demonstrate the best, most relevant track record), and also give you a feel for your culture. Rather than obsess over price, simply adjust your proposed team to reflect the client’s culture and demonstrate your deeper understanding of their needs and the challenges they face. If you are the best fit for the client, then it doesn’t matter that your price is higher than the competition (it couldn’t be ridiculously high, but there is no problem if it is the highest of the group). In addition, having meetings with the client gives you the chance to start creating chemistry between you, to show how you are similar to them and why you are the best (cultural) fit.

Key point

You do not need to obsess over your price. Being the highest priced offer wasn’t a problem (if anything it confirms your superior quality). Clients expect to negotiate price after they had chosen their preferred firm.

Clients often expect to negotiate on price after they have chosen their preferred firm. With that in mind, being higher than your competitors is not fatal to your success as the client will probably try to negotiate you down (how to handle this pressure to cut your pitch price is discussed later). There is an exception to this rule in relation to government, public sector or highly procured contracts where the client will seek first to prequalify who could do the work, and then after that will ask for a single bid and reserve the right to take the lowest bid (although not be bound to do so).

However, it is also in this area of Relationship Advice that clients are looking for alternative methods of charging by their service firms. My research revealed that there was real dissatisfaction with simply charging for the time taken. Clients were not simply looking for this to be addressed by negotiating discounts off hourly or daily rates, but were also looking for a different approach to pricing. Given that price was going to be a factor, if the client saw two firms that were very similar, then an offer by one of those firms to charge on a different basis (not just lower) could be decisive.

In fact, this was not just a matter of principle. Clients displayed a visceral dislike of charging based upon time spent for Relationship Advice, unless it was tied into a tight overall cost. It actually felt unprofessional and reminded clients of similar situations, such as where they called a plumber to their home to resolve a blocked drain and instinctively ‘knew’ that the plumber was not going to work quickly, and would be quite likely to find further problems, because the longer the plumber was on their premises the more money they would have to pay. Interestingly, there is ample research that shows that everyone displays this aversion to being charged ‘by the hour’. This is often called the ‘taxi meter effect’ and is a function of the fear of uncertainty that charging on a time-based system causes, so that a fixed fee is preferred even in circumstances where that leads to a higher overall cost2.

From a client’s’ perspective, these are the problems with the old way of unlimited time-based billing:

- There is no incentive for the service firm to be efficient or to develop any processes that would speed up the work. In fact the opposite is true, not just for the firm as a whole, but for all the individuals working on that client’s matters who would be under pressure to hit budgets and to record and charge for more time, and so have no incentive to work faster or more efficiently.

- The longer the matter took, the higher the bill. The more problems that were discovered, the more hours would be needed, and the more staff that became involved, the better for the firm.

- Clients are typically tied into annual budgets for spend. These cannot be exceeded; indeed, for a client to tell their manager that they had blown through an allocated budget could end their career. So how do they then cope with service providers who cannot agree budgets in advance?

- There is little link to value. It might take a long time to produce quite a poor result. Charging by the time taken simply passes on all of the costs and inefficiencies in the system to the client.

There is no alignment between the interests of the client and the interests of the firm; they are pretty much in direct opposition. This is hardly the ideal position for partners who are seeking to become trusted advisers to their clients, and yet Relationship Advice is the area where achieving that status is the most important.

Key point

One client complained: ‘Would you take your car to be repaired at a garage if you knew that every mechanic could earn bonuses based upon how many faults they found in your car?’

The level of dissatisfaction with time-based charging led clients in some areas of work to demand a change to fixed fees. Even where a project could not be specified in detail at an early stage, the client took the view that they were dealing with firms with considerable experience who should be able to draw on past data showing typical costs in order to create a realistic fixed fee proposal. In this way the client could compare the proposals from several possible firms before making a choice, safe in the knowledge that they were not going to go over budget. Even if a firm was reluctant to offer a fixed fee on an uncertain project, the firm will be told that all their competitors have agreed to do so and that if they fail to join in, then they will simply be excluded from the work. The more streetwise clients were still going to choose their advisers based upon track record and chemistry, but introduced a fixed fee competition to drive down the prices of their preferred firm.

Although a fixed fee sounds like a simple answer to all the problems, in practice it actually had as many shortcomings as charging for time taken:

- There is a real incentive for firms to bid low in order to win the work. Typically, firms do not have easily accessible data in order to create a realistic estimate of the work involved, the actual path of the work, and the time cost, could vary dramatically. This led to the typical fixed fee transaction running well over cost, made worse by the lack of fixed fee project management skills inside the firm.

- While the client may be unconcerned by the matter running well over its fixed fee, inside the firm the partner running the matter will find increasing reluctance of good people to work on it, given that all of their time is simply going to be written off.

- There is no incentive for the client to be efficient. The client could change their mind, substantially alter the terms of the project and argue over every issue. It doesn’t matter to them because they have a fixed fee no matter what.

Switching to fixed fees is not a sustainable solution for Relationship Advice. By definition this advice involves important and somewhat complex projects which cannot always be sufficiently specified in advance to create a realistic fixed fee. While firms may be prepared to take risks in order to keep the flow of work, it is very unlikely to be a sustainable, long-term business model.

Eventually, at my firm, I started to explain to clients who demanded a fixed fee on an uncertain project that their approach was a little like going for an operation but telling the surgeon that they only wanted to pay for two hours of their time, so that, at the expiry of the time they just wanted to be sewn back up, no matter at what stage the operation was. Because that was what was going to happen on a fixed fee deal – of course we would complete the job, but there would be real pressure to cut corners and reduce losses.

Key point

Switching to fixed fees wasn’t the simple answer that clients had hoped for. Transactions typically overran the somewhat optimistic fixed fee, and good people became very scarce.

It became increasingly obvious that it was this area of Relationship Advice that required the most focus on pricing skills. This is where service firms needed to up their game and behave just as more advanced businesses had for the last 50 years: devising clear pricing strategies, developing a better understanding of the market and, as a result, being able to produce prices and a method of charging that would be both profitable for the firm and realistic for the client. The aim is to build long-standing, mutually sustainable relationships with your clients. This is the primary area of focus for this text.

PRICING ROUTINE WORK

Fixed fee. It is almost as simple as that. When it comes to Routine Work, clients are expecting a fixed fee and even if it is accepted that some pieces of work will take substantially longer than others, the firm will be expected to average these out so that a single fixed fee can be charged. This is the case whether a single client is providing sufficient volume to average out the cost, or the volume comes from a group of clients.

Procurement could be expected to be involved in producing a tight specification and running bidding processes (quite frequently online). This is definitely not an area for relationships. Clients would move the work for a relatively small difference in price. Partners who excel in this work are good at process, data and creating and managing junior teams. The best excel at continuous improvement and designing their service to closely match the client’s needs. Despite its downmarket image, many highly reputable firms are able to produce substantial profit from highly leveraged teams, leading to a high profit per partner. Just as budget airlines often carry more passengers than the national ‘flag carrier’ airlines and earn more profit in a typical year, so it is with Routine Work.

Provided that a relatively low-quality hurdle could be met, lowest price, combined with evidence of an ability to cope with the planned volumes of work, was pretty much the deciding factor. However, clients did show a willingness to pay higher prices for differential services. In other words, the best of the firms actually take time to understand what might make the service being provided on Routine Work more valuable to the client. Given that Routine Work typically arrives in substantial volumes, small changes in price can have a very substantial effect on profitability. Not untypically, a 1% improvement in the price being charged increases the actual profit on this work by 10% or more.

Key point

Even in this most commoditised area of work, there are opportunities to differentiate your firm and to earn higher fees as a result.

This means that there are opportunities for value-based pricing. For example, you could say that Price 1, the lowest price, is to be charged per matter provided that certain performance criteria were met, but Price 2 and Price 3 will be charged if specified better results are achieved. This appeals to clients because it met a need for continuous improvement and extra payments are only triggered if the better performance is actually delivered. It allows a firm, even in this most routine and commoditised area of work, to create a differentiated service. The firm could say that its aim is not to be the cheapest firm delivering the most basic level of service, but to be better than competitors and to earn more fees as a direct result of delivering better outcomes.

Understanding the client’s drivers of value, as discussed in Chapter 8, is particularly relevant to this type of price variation, which depends upon facts and data. This is not an area for grand and fuzzy claims to be better than competitors.

With these fundamental pricing principles in place we can now examine how we can put this into practice to improve firm profitability. Unfortunately, this is not simply a matter of increasing prices. If it were that simple, then no books would have been written on the subject. It is about using the inherent flexibility of services delivery to your advantage. With services, a unique feature is that the terms are agreed before the services are delivered; they are intangible and you can agree with the client the actual type of delivery as part of your negotiations. Contrast this with the typical situation for physical goods, where a supplier may have a warehouse full of the completed product that they need now to sell, with little chance of alteration.

As a next step, it is important to understand the most basic principles behind how the price of services is calculated, what options are available, and which will have the best chance of improving profitability while maintaining client satisfaction. It is to this topic that we will now turn our attention.