CHAPTER 12

WHY IT WORKS

What use is it to know why and how coaching works? You may not care. Some have no idea what happens under the bonnet of their car, they just want to turn it on and go. You may feel the same about coaching. On the other hand you may be curious, for several reasons: innate curiosity about most things, or a desire to know in order to do it better or faster, or to know how to fix it when it goes wrong. If you’re in the ‘just turn it on and go’ camp, then you might like to skip this chapter.

Still here? Great!

This chapter considers:

- 1simple practical reasons why coaching works;

- 2reasons from scientific research;

- 3the research basis of Big Five coaching; and

- 4reasons from scientific research: allied fields.

1. Simple practical reasons why coaching works

At one level, I believe coaching works for basic common-sense reasons.

Pause

It’s that nice Mr Edison’s fault. Before the lightbulb, wax candles were expensive, tallow smelly, rushlights dim, so unless there was some special need to struggle on peering through faint light, the vast majority of workers stopped at sundown. In the last 100 years, average working hours have gone up and average hours of sleep down. The Oxford English Dictionary says the phrase 24/7 appeared in 1983 (in the USA; 1997 in the UK) and, with it, ever-on communications, food delivered to desks and sleeping cells in firms’ basements.

Fifty years ago senior businesspeople were mostly men, with wives to ensure there were clean shirts and nourishing meals. Fifty years before that there were staff. Now we all work, and cram the other things in somehow. Our families are in another city, or country, and friends are busy too, so if you want support you need to pay for it – and organise it – more to think about. And technology, of course. (When I started proper work in 1977, a letter was posted and you could rely on at least a week’s grace before the reply was posted back to bother you again.)

In sum, most normal people in business have an enormous amount on their minds. On good days, it’s fun and exhilarating, but it doesn’t take much to push it over into stress.

Coaching works because for an hour, or two hours, or even just a minute waiting at the lift, it presses the pause button. Sometimes it’s enough for a client just to have a space that is calm, quiet and where silence can be constructive. It’s no coincidence that the rightly famous coach Nancy Kline, and indeed many great business dynasties, began as Quakers.

Clearing your head

I have a client with huge responsibilities. Most sessions he arrives late, stressed, papers bulging out of his briefcase, and his head in a similar state. Whatever work we do together, the main value to him is almost always that by the end of the session he has sorted through everything he has on, realised some things must be delegated/declined/pushed back, and reconnected with the key things to focus upon. He arrives stressed, sometimes almost overwhelmed by all that has to be done, and often disaffected. He leaves 90 minutes later with a clear head, and hence re-energised and re-motivated.

Venting

There’s a lot in business to fear, hate and be anxious about – or even excited and joyful. Yet senior executives often need to play their cards close to their chest. No one can know, yet, that the finances are so close to the brink, or the breakthrough research discovery is about to pay off. One of the formative experiences all new business coaches go through is when a client comes to the session and instead of working obediently through the GROW Model, or coming up with fiendishly clever strategies, they spend the time pouring out their anxiety, or fear, or anger, or excitement. Nowhere else is safe for them to do it. If it’s minor, they’ll get it off their chest and move on to ‘proper’ coaching; if it’s major it’s the coaching topic itself.

Time

We all know we should, but in practice few of us actually block out time in the diary to think. Instead we rush from one project to the next, constantly feeling overloaded and behind the game; the urgent pushes aside the important, we fight fires instead of focusing on what really matters.

So the coach helps simply by showing up – time is blocked out in the diary, the phone is parked, and the executive has an hour or hour and a half of quality thinking time. I sometimes say to clients, you could replace me with a decent sheet of wallpaper – just block out the same length of time, look at the wall, and think: it’s cheaper. (The difference between me and wallpaper is I fight back; if they get to the point where the wallpaper does too, coaching isn’t the answer.)

Many clients say the single biggest value from coaching is ‘it gives me space to think’. When we pull back briefly, we see priorities more clearly. Just space to think means clients pick up a lot of the ‘low-hanging fruit’ in coaching – the simple idea or improvement that’s been brewing for a while but never had space to pop out: the ‘oh, now I stop and think it’s just so blindingly obvious . . . ’.

Sounding board

Executives often say the great value for them in coaching is to have a ‘sounding board’. Particularly if they’re really senior. The issue may be about the board, so they can’t share it with them, and they have to look confident with the next layer down. They’ve been working so hard they’ve lost touch with the old friends; the long-suffering first spouse has heard it all too many times before, or has gone, and the hot younger number gazes incomprehendingly. Lawyers, financiers, advisors, all have a stake in the decision. You see why an intelligent sparring partner whose discretion can be utterly trusted, who will challenge fearlessly, yet who is 100 per cent on your side, is precious. I’ve been through three bad recessions now, and senior executives don’t let go of their coaching if they can possibly help it: the tougher it gets, the greater the need, and the more fiercely they protect that space.

Speaking truth to power

As noted above, the difference between me and a sheet of wallpaper is I fight back. This role has a long history – rival nobles daren’t tell the king the truth, but the court jester could, as long as he was made to seem harmless with the cap and bells. Modern business coaches find their own ways of getting the message across in a way it will be heard.

2. Reasons from scientific research

Why does this matter?

According to the old joke, an economist is someone who looks at what’s working in practice and asks if it would work in theory. I used to laugh at that, now I am that economist/business coach: I believe it’s not enough to know in practice that coaching works, or to guess at some common-sense explanations for its effectiveness. We also need to be able to demonstrate scientifically that it works, and why. There are at least three reasons for this:

- ●Professional bodies can be expected to get ever tougher, with complaints procedures against coaches developed and sanctions enforced. Tests in such cases include what a reasonable person could be expected to have done and/or whether the coach abided by best practice. A coach who can demonstrate they are trained in, and use, only methods grounded in reliable evidence-based science should be safe – but first we need to know what those methods are.

- ●In tough economic times, the demand is for higher-quality services, delivered ever faster and more cheaply, including by CoachBots. If we don’t know why and precisely how coaching works, then we can’t strip it down to the essentials and rebuild it to meet evolving demands, such as algorithms to make coaching more widely accessible.

- ●Consider a different field. In his classic text on architecture, Sir John Summerson said the period 1753 to 1768 was crucial in British architecture because:

from this period we can date the real existence of an architectural profession, a profession to which young men [sic] are trained up and not merely one whose members have all either graduated from a trade or have adopted through a combination of circumstance and predilection, often late in life.1

Coaching is currently going through the same vital years of transition. To become a full profession we require a theoretically valid, empirically based and rigorously tested body of knowledge that is widely agreed upon and subject to constant further development, evaluation and review. This in turn will enable us to make our work, and its impact on people, teams and organisations, explicit, measurable and verifiable.

What is scientific research?

Proper scientific research differs from the business research with which we are more familiar. The objective of business research is often to provide the sort of information that enables organisations to take more informed decisions, usually by describing what is happening. Do customers prefer green ones or purple ones? What are competitors up to? Scientific research by contrast may also seek to describe, but at heart it has a more challenging objective: to explain what is going on.

The philosopher J.S. Mill articulated one set of requirements to be met before one can actually claim to have explained anything. Before A can be said to have caused B – for example, before you can say that coaching causes increased performance – he says the following conditions must be met:

- ●A must precede B.

- ●B must covary with A (i.e. if A pushes, B moves).

- ●All other explanations must be ruled out.

Clearly it is difficult to satisfy such rigorous criteria when dealing with complex, mutable scientific subjects like humans. Though not impossible: psychology, for example, is full of ingenious experiments where precisely these conditions have been met and aspects of human behaviour illuminated.

Furthermore, good scientific work usually develops from an established theoretical base, investigates in the light of that theoretical paradigm and builds up therefrom a body of tested evidence. (Hence the phrase ‘evidence-based’.) Science also prefers explanations that are ‘parsimonious’ that is, the very simplest and clearest explanation is the best. (Which is why those who could fathom it, got so excited about E = mc2.) Experiments must be conducted according to tight rules of procedure and ethics, and in general the results must meet the standard of being statistically likely to the magic level of 0.05 per cent: in other words, the chances of the outcome of the experiment happening by chance are less than 5 per cent.

How can you tell if coaching ‘research’ passes these tests? There is one shortcut. If ever you find yourself at a Nobel cocktail party and are at a loss for small talk, mutter quietly, ‘of course, in the reviewed journals . . . ’ and bask in the respectful silence. The ‘peer-reviewed’ journals are a benchmark for scientific rigour and respectability. All sorts of procedures exist to try and make sure that if something ends up being published in these famous journals, the science in them is sound.

Like everything else in life, there is a hierarchy. Atop the pecking order is the journal Nature; if ever an approving article on business coaching appears there, then we’ve arrived. Coaching being a relative newcomer in the research world, our peer-reviewed journals are currently rather lower down the pecking order, but they do exist. Currently there are three and a half of them: Coaching:An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, the International Coaching Psychology Review (ICPR) and the Annual Review of High Performance Coaching and Consulting (ARHPCC). The ‘half’ is the Consulting Psychology Journal, which is my favourite. It’s not officially dedicated to coaching (it’s the journal of Division 13 of the American Psychological Association), but US scientist-practitioner executive coaches have semi-colonised it, and it frequently has good to excellent special issues on top-level coaching.

The scientific research on coaching

So how much parsimonious, theoretically sound, accurate to 0.05 per cent coaching research is there?

Not much, but that’s changing fast. A scholarly review in 2001 by Dr Anthony Grant found only 17 acceptable scientific studies of coaching interventions.2 By 2015, when Drs Andromachi Athanasopoulou and Sue Dopson published their landmark Developing Leaders by Executive Coaching – which usefully pulls together all the academic research to date on leadership coaching – it took an entire chapter (Chapter 4) to list and critically analyse the hundreds of studies they identified.3

That’s good, but there’s lots more still to be done.4 In brief, we don’t yet have, and need, documentation of the theoretical sources of coaching; published statements linking the theoretical sources and how the interventions are operationalised; agreed standard procedure(s); and testing of coaching’s efficacy, in individuals, teams and organisations.

Examples of studies published so far, from the old but still useful, to the much newer, include:

Olivero, Bane and Kopelman: Combining coaching and training improves productivity5

This pioneering ‘action research’ found training alone increased productivity by 22.4 per cent, but training combined with follow-up coaching increased productivity by 88 per cent. The authors noted that as the study was live research done ‘in the field’, i.e. in a real business context with all its complexities, there must be many caveats on their findings, but the magnitude of the results was such that they had some confidence in ascribing the astonishing performance outcome to the coaching. They further broke down the coaching into seven key elements, of which they thought two, goalsetting and having to make a public presentation of the results of the coaching (a feature of that particular project; in a way, a compulsory W of GROW), were the two most important. You may raise your eyebrow at the numbers, particularly the 88 per cent. But this study was the first to make the point, now widely accepted, that sending people away on a training event can be a complete waste of money, unless you do something significant to ensure they don’t forget the lot when they get back. Coaching to embed the new learning and make it their own, is simplest.

Real estate salespeople: coaching improves sales performance6

A coaching programme explicitly based in cognitive behavioural psychology was introduced for real-estate salespeople in a firm that previously had poor sales performance and high staff turnover. The subsequent evaluation found a number of benefits, including increased sales, and client and staff satisfaction. For example, the time for a new sales associate to get their first property listing fell to 3.53 weeks (compared with an industry average of 10 weeks), which represented a first month commission of $2,430 compared with an average of $871 for those who did not participate in the programme. (This is another aspect of good scientific work – the experimental group is matched with a ‘control’ group, who differ in no way other than the experimental intervention.)

Coaching in teams7

In a study that looked inter alia at the role coaching plays in teams, Ruth Wageman found that team basics were more important than team coaching. (Katzenbach would applaud.) In other words, having the right team members who were properly selected, resourced, trained, etc. had more impact than good coaching. However, in teams that were well constructed and managed, good coaching had a powerful impact. Here again we see (as in the Olivero et. al. study above) the additive effect of coaching: allied to existing good management practices it makes the latter’s impact more powerful.

3. The research basis of Big Five coaching

Let’s look at this from another perspective. In Chapter 5, I outlined the basic foundations of coaching:

- ●contracting;

- ●GROW, including goalsetting;

- ●listening;

- ●questioning;

- ●non-directive.

How much of this is tested to scientific standards?

As a combination, none: this book is the first time the ‘Big Five’ bedrock of business coaching has been articulated in this particular way. But many of the component parts have been, namely:

Contracting

You may recall from Chapter 6, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow model. Flow is securely based on exhaustive research, spanning most of the world’s cultural contexts, genders and age ranges.8 One of the first four of Csikszentmihalyi’s ‘9 conditions of Flow’, i.e. the crucial preconditions of peak performance, is boundaries. It may seem odd to some in our modern free-wheeling world that humans perform best where there are rules and limits (though the traditional English nanny always knew it) and here’s a reason: boundaries make people feel safe, and build trust. Comprehensive contracting establishes those safe boundaries.

Therapists have long recognised this, and use many techniques to contract and hence create safe boundaries. One example is the sanctity in some therapeutic approaches of the 50-minute hour: no matter how bad it gets, even if you are sobbing, you know that, without fail, a few minutes before 10 to the hour, the therapist will pass across a particularly large handful of tissues and say, ‘Well, we need to be bringing this to a close . . . ’.

So contracting has in some senses been tested to high scientific standards, and it’s also based on long-established practice in a different field; more research is needed on how it can be optimised in business coaching.

GROW, including goalsetting

GROW has not been subjected in its entirety to scientific research. But its arguably single most important element, goalsetting, certainly has been.9 In mainstream psychology, already by 1975 Latham and Yukl were reporting 27 separate studies, under laboratory conditions or in the workplace, many with hard outcome measures such as ‘net weight of truck loads’ or ‘dollars collected’. Similarly, Kolb and Boyatzis found positive behaviour change was greater in goalsetting than in non-goal conditions in personal development work. In 2013 Locke and Latham (the most famous collaborating pair in this research) published a major article summarising decades of work around the world.10 The original proposition still held: in essence, the more crisp and clear the goal at the outset, the higher the performance at the end – but not always. Four decades of solid research have, though, given us a subtle and nuanced understanding and application of goals – see Tony Grant’s chapter on goalsetting in Evidence Based Coaching.11

Listening, questioning and non-directive

We have seen for almost five decades that these work, and powerfully, in the client-centred approach of humanistic psychology, whose leading thinkers included Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers. But though this has become the basis of much of modern counselling, humanistic/client-centred approaches have been criticised for not sufficiently subjecting their approach to empirical testing.

Positive Psychology (PP) – described by one of its founders, Martin Seligman, not entirely tongue in cheek, as ‘Maslow plus science’ – is putting that to rights. Seligman alone has raised over $30 million for research, much of it directly relevant to coaching, which he has designated as one of the core delivery mechanisms for Positive Psychology. Already there is a rich outpouring of quality research relevant to coaching: by far the most comprehensive description is by Carol Kauffman in Evidence Based Coaching,12 but more research arrives by the day.

A sub-field applying all this to business has sprung up: see Positive Organizational Scholarship,13 which has all the big names, including (the sadly late) Donald Clifton on strengths at work; Barbara Fredrickson on the business impact of positive emotion; David Cooperrider on Appreciative Inquiry; and Fred Luthans and Bruce Avolio on authentic leadership development. But not, you will note, anyone on the utter basics of listening, questioning and non-directive. This is the way of science, which often (game-changing Newtons and Einsteins apart) begins with myriad small studies and monographs, and is only then able to develop the super-perspective needed for synthesis of the core components. But as quality PP research is now proceeding apace, it may not be too long.

4. Reasons from scientific research: allied fields

While we are waiting, many allied fields have long-established, reputable work that we can draw upon – indeed we already are. We can’t yet definitively claim that coaching works because it is securely grounded in this research, because it isn’t: we have borrowed it, and are using it in practice to good effect, but for our field to be fully robust, each borrowing needs to be rigorously tested in our specific business coaching context. We see in practice that the borrowings work: we need to use that to form good theoretical hypotheses, and test those out, in order to deepen our understanding and make more secure the foundations of our practice.

If we peer over our neighbours’ fences, some of what we see, which has been scientifically tested over there, but not yet over here, includes:

- ●from psychotherapy: the ‘common factors’;

- ●from cognitive psychology: cognitive load/limit to working memory;

- ●from organisational psychology: cross-cultural coaching;

- ●from Positive Psychology: lots;

- ●from neuroscience: why it works, at brain level.

Psychotherapy and the ‘common factors’

Pushed in part by spiralling medical costs, there has been considerable research over the last 40 years in the field of psychotherapy on whether ‘talking therapies’ work, and if so how. The consensus is they do work, and there are four reasons why.14 To the discomfiture of the warring factions, which specific therapy is applied accounts for little of the difference.

Instead, four ‘common factors’ (Hubble and Miller, 2004) are said to be shared by all effective therapies. These are not definitively established and tested but are instead conceptualisations to enable future research investigation to be more focused, but they are interesting nevertheless.

The four are:

- 1The client/extratherapeutic factors: accounting for 40 per cent of the estimated contribution to treatment outcome. These include factors such as the client’s strengths, supportive elements in the environment (e.g. a kind grandmother) or even chance events such as a good day at the races.

- 2Relationship factors: accounting for an estimated 30 per cent of the treatment outcome. These include ‘caring, empathy, warmth, acceptance, mutual affirmation, and encouragement of risk-taking and mastery, to name but a few’. (Hubble, op. cit., p. 341.)

- 3Placebo, hope and expectancy: accounting for 15 per cent of the estimated contribution to treatment outcome. This derives from ‘clients’ knowledge of being treated and assessment of the credibility of the therapy’s rationale and related techniques . . . [i.e.] the positive and hopeful expectations that accompany the use and implementation of the method’.*

- 4Model/technique factors: accounting for only 15 per cent of treatment outcomes.

* Hubble, op. cit., pp. 341–2. Don’t knock a good placebo effect: medicine uses it all the time.

The above may cause you to raise an eyebrow, but remember this is about therapy, not coaching. Therapy normally works with potentially unwell people seeking personal healing. Business coaching works with healthy people, teams and organisations seeking business outcomes, so all sorts of different factors are at play.

Second, the common factors view is controversial even in therapy (but has some heavyweights behind it).

Third, even if it has something to say to us as business coaches, the organisational setting, and particularly the tough worlds most senior coaches operate in, will doubtless skew the percentages – though I’m not sure which way. Client and client context factors are estimated to account for 40 per cent in therapy. Our clients are not ill but well, and not just healthy but more intelligent, more driven and more pathological* than the general population – so does a more dominant client mean that number is in fact higher in coaching? Alternatively, organisational settings are full of other people just as determined as our clients, plus tough legislative constraints, powerful role stereotypes and expectations (e.g. what a first-rate chairman/CEO should do), etc. – does this mean it’s less?

* More intelligent: at least one standard deviation above the norm, i.e. an IQ of 115 or above is required to succeed in management levels and up according to Professor Adrian Furnham (Address to Meyler Campbell Psychology for Coaches course 2008); more driven, look around you; more pathological, see Babiak, P. and Hare, R.D. (2007) Snakes in Suits. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

In other words, it might be that since our worlds, and the work we are contracting to do, are both so different, that the ‘common factors’ debate in therapy may be irrelevant to us. We won’t know until significant research on this is done in our own business coaching context. (You may well have your appetite whetted to read more of Hubble’s and Miller’s chapter, and I do indeed recommend both that and the entire Linley and Joseph book.15 It’s a full-on dense academic tome, but a brilliant one – my own copy has pencilled scribbles, underscorings and exclamation marks down the margin of almost every paragraph. Apart from the one (Kauffman, 2004) chapter already mentioned, it’s nominally not about coaching, but the greater part of the book is in a deeper sense directly relevant.)

In the meantime, if even part of ‘common factors’ is right, then to me it reinforces the importance of Big Five coaching: contracting in the business context starts by taking careful account of the client and what Hubble and Miller call ‘extratherapeutic’ factors – we would say, the business context – and anchoring the coaching accurately for that unique organisation and client; GROW provides the necessary model framework and established expectation on both sides of success; and listening, questioning and non-directive provide the conditions for relationship factors, and client resources, to flourish. (In fact, I sometimes think GROW operates as ‘trainer wheels’ for high-achieving businesspeople learning to coach: it keeps them occupied and stops them doing what they would otherwise have done (telling clients what to do, etc.), thereby allowing the client’s thoughts and solutions airtime. Great coaches can transcend GROW, but coaches in training need to go through strict adherence to it in order to get to that point. Another Myles Downey phrase is, ‘In coaching, there are no rules, and you have to know them.’)16

Cognitive psychology: cognitive load and the limits to ‘working memory’

Do you know your blood type? If you are like me an O blood group, then I’m afraid to tell you our blood type is very old, possibly even Neanderthal. If on the other hand you are from the A/B blood groups, then you have a new type, which developed only 10,000 years ago, when humans moved from nomadic existence to settled agriculture. And that, I have been told, is the last major innovation in the human body.

Which means our brains are coping with the 24/7 life described above, with a brain that has many accretions, but is at its core, Stone Age.

Yet today with all the noisy visual clamour of our modern advertising-blitzed, communications-dense overcrowded age, it has been estimated that in any nanosecond, there are coming in upon us 300,000 bits (in the computer sense) of information. Cognitive psychologists however say our ‘working memory’, the essential ‘desktop’ of the brain where we process current information, can handle only ‘seven plus or minus two’ bits of information at any one time. That is, we can all, on average, hold only about seven things in our conscious mind at once – which is why for example, telephone numbers in every country in the world are broken up into manageable chunks as soon as they get longer than about seven digits.

If we’re being blitzed with 300,000 bits of information each split second (noise, sights, barometric pressure, gravity, sensation, etc.) yet can only process 7, how on earth do we cope? Partly by habits (I drink my tea black – saves having to think about it), heuristics, patterns, routines. But we still often feel – and are – overloaded.

Cognitive psychologists haven’t so far as I know researched how coaching helps with that, but I hypothesise it is in two ways, through downloading and organising. In coaching sessions clients download a lot of current material, not just to the coach but also onto their phone/paper/computer – action plans, etc. – taking a load off current memory and attention. And coaching often causes clients to organise, delegate or deal with the incoming data stream and existing backlog. But these are just hypotheses and remain to be tested. The sharp contrast between what working memory can cope with, and the deluge of information, is however an established fact.

Organisational psychology: cross-cultural leadership

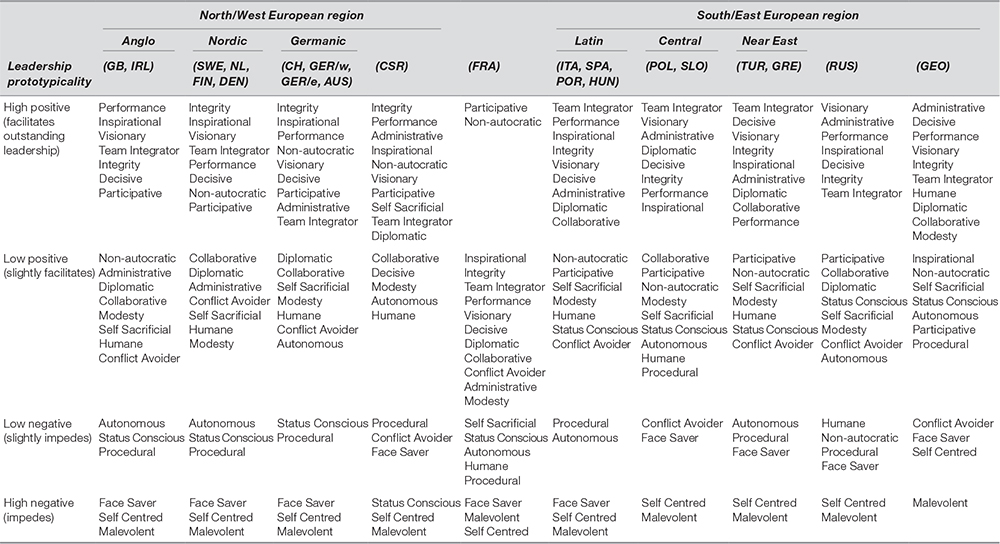

One huge piece of research from organisational psychology points to why on occasion coaching doesn’t work – and how we need to adjust so it does. Part of the enormous GLOBE project, Felix Brodbeck and others have looked at differing leadership paradigms in each of 22 European countries.17 Anyone coaching in Europe will probably want to see the full data (which is unfortunately buried in particularly inaccessible psychologistese) but it is helpfully summarised in the report’s Table 3, reproduced here as Table 12.1.

In essence, the report’s finding is that, despite the external similarities of laptops, business suits, cappuccinos and LinkedIn, there are deep and significant cultural differences in what an effective leader does across Europe. The real richness for business coaches is the detailed breakdown of the ideal leadership paradigm for each country (outlined in Table 12.1). For example, a French coach working in the Czech Republic (or vice versa) should note carefully that being ‘self-sacrificial’ is an essential element for outstanding leadership in the Czech Republic; in France by contrast it is seen as an impediment. Mining this data – and the comparable data sets that have been published since for 62 countries round the world18 – should be an essential part of the well-briefed business coach’s toolkit if they coach at senior levels in any of the reported cultures.

Positive Psychology

I won’t say too much more about this here, as there has already been much about Positive Psychology and the underpinning science of why it works in this book. In particular, we saw Carol Kauffman’s ‘4 steps to confidence’ tool and PERFECT toolkit in Chapter 6, and several approaches to Strengths in Chapter 7. There is a vast further wealth of riches for business coaches to draw upon, but this has been comprehensively described by Carol in her book chapter already cited.19

Table 12.1 Leadership attributes in 22 European countries/country clusters

Key: AUS = Austria, CH = Switzerland, CSR = Czech Republic, DEN = Denmark, FIN = Finland, FRA = France, GB = United Kingdom, GER/w = Germany, GER/e = former East Germany, GEO = Georgia, GRE = Greece, HUN = Hungary, ITA = Italy, IRL = Ireland, NL = Netherlands, POL = Poland, POR = Portugal, RUS = Russia, SLO = Slovenia, SPA = Spain, SWE = Sweden, TUR = Turkey

Source: Brodbeck, F.C. et al. (2000) ‘Cultural Variation of Leadership Prototypes across 22 European countries’, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73, pp. 1–29.

But, there is just one further crucial insight from PP that I would like to flag: the Fredrickson/Losada Ratio.

Our starting point is that the brain is hard-wired to negativity. This makes Darwinian sense – for almost the entire length of human history it was a matter of life and death to be alert to the negative in our surroundings – the fire is about to go out and we will all die/watch out that dinosaur is about to eat you. (Having used this example for years, a 13-year-old recently gently informed me that dinosaurs and humans didn’t in fact co-exist – pity, it made such a great story.) Noticing those things enabled the body to flick into ‘fight or flight’ response and, as a result, the human race survived. Now, however, the fact that the old parts of our brains and nervous systems constantly fire under threat is no longer helpful: trigger-noises or events happen all the time, and we end up with high blood pressure. Conversely, perhaps for equally sound Darwinian reasons (there were times when this too was useful, though fewer of them), Barbara Fredrickson has found that positive emotions have beneficial effects on our brains and bodies – the ‘broaden and build’ effect. If we are in positive mind frame, we are able to generate more creative solutions, think more expansively, and perform better at the sort of complex tasks that are better suited to today’s more cerebral world; though remembering the hardwiring to negativity, it takes conscious effort and practice to ‘reverse the focus’ to what’s right about things.

At different times and in different combinations, Fredrickson, Losada and Heaphy have done a number of studies20 of high-performance individuals and teams to explore how those conflicting forces, i.e. our natural predisposition to negativity, and the positive benefits of positive emotion, play out in the real world of business. In detailed analysis of team interactions, they found that the highest performing teams were those where the optimal ratio of positive to negative feedback was, in varying contexts, from 6:1 to 3:1, i.e. three positives for every negative. Not, as people assume, the teams where the ratio was only 1:1, that’s not enough for peak performance (it doesn’t counteract the hard-wired bias: people seem to need to hear 3:1 or above to experience it as evenly balanced), and also interestingly, not in a team they found where it was 13:1 (who were those people?!). Leading-edge organisations are already building the 3:1 ratio not just into their coaching but into performance appraisal systems and training programmes.

Neuroscience: how the brain changes through coaching – maybe!

If you can read just one further book this year, or in the next many years, my humble suggestion would be Norman Doidge’s game-changer, The Brain that Changes Itself.21 The blurb on the dust jacket says the methods described result in ‘blind people who learn to see; learning disorders cured; IQs raised; ageing brains rejuvenated; stroke patients recovering their faculties; entrenched depression and anxiety disappearing; and lifelong character traits changed’. Yet astonishing as it seems, this is reputable work, world-class even, and deeply rooted in sober science.

In essence the research described overturns traditional notions that the brain peaks at about 16 and it’s downhill, and fixed, all the way thereafter. Instead, high-precision modern neuro-imaging techniques have found instead that the brain rewires constantly – hence the ‘neuroplasticity revolution’.

One specific technique described is ‘focused attention’ which is central to the transformations described. The neuroscience of this is Nobel prizewinning work on nerve growth factors, including one called brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF. Under conditions of focused attention BDNF consolidates the connections between neurons; promotes the growth of the thin coating of fatty myelin around them; which in turn speeds up the transmission of electrical signals. Altogether these add up to a ‘magical epoch of effortless learning’ which characterises childhood, and is activated thereafter only when something important, surprising or novel occurs – or when both clinician and patient are paying close attention to a task set up for the treatment.

So this could explain the brain process underlying much of what we have learned in this book: the need for deep listening, highly disciplined and targeted questions, and the crucial importance of tightly focusing goalsetting. Focused attention changes the brain. (So having to pay close attention is brain-enhancing for the coach as well!)

Most interestingly of all, the changed brain chemistry and increased plastic rewiring ability generalises beyond the immediate task: BDNF puts not just the part of the brain required, but the entire brain, in an ‘extremely plastic state’. Over time the more this happens, the more completely unrelated parts of the brain are also roused into higher performance. So that pattern you may have noticed, where people who have practised with deep attention for years at one thing (playing the piano for example, or maritime law) also seem to become unfairly good at many other things – sport, deep connection with friends and family, writing poetry. A good hard consistent workout for one part of the brain seems to exercise and energise the whole system.

I have always said, not entirely in jest, that one reason for the rise in coaching is because children are no longer taught the classics. I presumed the extraordinary ability of well-educated 19th-century public schoolboys to survive and flourish in all the remote and inhospitable corners of the Empire to which they were sent, was because the classical syllabus drummed into them, taught them to think with exceptional clarity. And so it unquestionably did – but it may also be generalised BDNF at work again. Classics students at Cambridge in the 1830s for example worked for years at an almost unrelenting peak of focused attention, combining the most rigorous training of their minds with demanding physical exercise every day.22 Did that give them exceptional brain density and neuroplasticity?

Focused attention on good things builds the brain – but what of the reverse? We are aghast in history lessons on the Middle Ages when we learn that raw sewage ran down open drains in the streets, and people emptied bedpans out of windows onto the heads of passers-by. Knowing the Fredrickson/Losada Ratio, will future generations look back with equal horror on our constant diet of (often negative) ‘news’ and social media trivia, seeing this as the psychological equivalent of medieval raw sewage pouring through our minds?

But I digress. The next chapter is about how to build your business as a coach.