Chapter Four

![]()

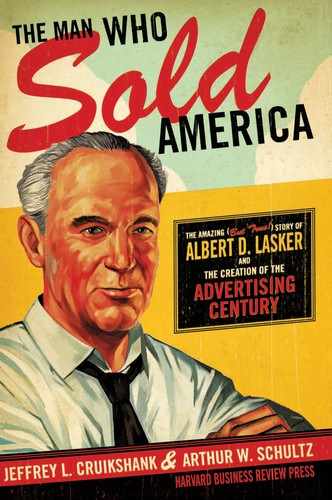

Salesmanship in Print

![]()

SHORTLY AFTER arriving in Chicago, Albert Lasker wrote a letter to his father. He was worried, he confessed, because he couldn’t resolve his fundamental confusion about the advertising business: “The great force of advertising has been shown to me in the short time I have been here. People are spending what to you and me are inconceivable sums. They are getting results, or they could not keep it up. Yet I haven’t been able to find the man who could tell me what advertising is.”1

Lord & Thomas’s slogan was “Advertise Judiciously.” But no one at the firm could explain exactly what that meant. “Well, spend your money carefully, in the right papers,” his colleagues told him.2 At the rival N. W. Ayer agency, the corresponding slogan was “Keeping Everlastingly at It Brings Success.” Lasker sat down with a counterpart from Ayer one day, and grilled him on the meaning of this slogan:

“Now,” I said, “here, let me ask you this. Supposing I start wrong and I keep everlastingly at it. Where is that going to get me?”

“Well,” he said, “what they meant was, keeping everlastingly at it right would achieve success.”

“Well,” I said, “What is ‘right’ in advertising? Can’t you define it for me?”

“Why,” he said, “keeping your name before the people.”

“Well, I said, “supposing I can’t live that long. Supposing I go broke; that I can’t keep my name before the people. There must be something else to this thing.”3

Lasker started scrutinizing all the ads in newspapers and magazines and on the new advertising phenomenon—billboards. Most of what he saw only puzzled him further, because there appeared to be no underlying theory. Advertisers seemed to have no plan. Lasker loved ideas, and his industry seemed bereft of them:

Well known advertisers were the Gold Dust Twins, that showed a picture of a couple of little cupids and said, “Let the Gold Dust Twins do your work.” Another was a picture of a nice little girl, and it said, “How would you like to have a fairy in your home? Use Fairy Soap . . .

Another was Armour’s “Ham what Am.” The Negro would say, “The ham what am—Armour’s.” And the next time you would see that ad, it would be an Italian, and he said, “The ham was ees—Armour’s.” The next time you saw him, he would be a German, and he said, “The ham vat iss—Armour’s” . . .

Well, that was what advertising was, do you see, keeping the name before the people. And of course, in the competition to keep it before the people, most of them got to kidding their own names—about the worst thing you can do.

That was advertising: sloganizing.4

Gradually, though, Lasker became aware of the work of a Chicago-based competitor: the Charles H. Fuller Company. Fuller had recently signed up breakfast-food maker C.W. Post, and the advertising that began to appear in support of Postum and Grape-Nuts struck Lasker as decidedly different from the vapidity of the Gold Dust Twins. Fuller wrote and ran ads that looked exactly like newspaper copy—in the same typeface as the newspaper—and told stories about happy users of the products in what Lasker called a “newsy” way.

Maybe, Lasker speculated, that’s the answer: Advertising is news.

Then again, maybe it wasn’t. Other departures in advertising also intrigued Lasker. A patent medicine firm in Racine, Wisconsin—Dr. Shoop’s Family Medicines—was running an ad with a provocative headline: “What Tea-Drinking Does for Rheumatics.” Every time he saw this ad, Lasker stopped and read it, even though he didn’t use patent medicines, didn’t have rheumatism, and didn’t drink tea. Why was that concept so striking? It wasn’t “newsy,” exactly. So what was it?

One evening in May 1904, around 6:00 p.m., Lasker was in Ambrose Thomas’s office discussing the business of the day. A messenger boy came into the office and handed Thomas a note. The older man scanned the note, chuckled, and tossed it across the desk to Lasker.

Written in a striking hand, the note read:

I am in the saloon downstairs. I can tell you what advertising is. I know you don’t know. It will mean much to me to have you know what it is, and it will mean much to you. If you wish to know what advertising is, send the word “yes” down by the bell boy.—John E. Kennedy

Thomas dismissed the note as the work of a crank, and suggested that Lasker ignore it. But Lasker, intrigued, sent his response back downstairs: Yes.

He retreated to his office and awaited the arrival of his visitor. Within a few minutes, a man strode in looking every bit as striking as his handwriting—six feet tall, with piercing blue eyes and a heavy blond mustache. Kennedy’s wavy dark blond hair crowned an expansive forehead—a physical characteristic that Lasker considered a sign of high intelligence. Although he was then in his late forties, he looked years younger. Lasker thought his guest to be “one of the handsomest men I ever saw in my life.”5

Lasker got straight to the point: “Well? What is advertising? Tell me.”

But Kennedy was not forthcoming. In subsequent years, Lasker told the tale of this initial meeting many times, and each version was slightly different. Reminiscing in 1938, Lasker recalled that Kennedy was “reluctant” to answer the question. Before giving anything away, Kennedy made it clear that he wanted to strike a business arrangement with Lord & Thomas—and that he “wanted to make it guaranteed.”6

So Kennedy bought time and fueled Lasker’s curiosity by telling stories in a commanding tenor voice about his allegedly colorful past:

The caller told me that for several years previous, he had been in the Canadian Northwest Mounted Police. And for reasons unfathomable to me, he had become interested in advertising.

Vivid in my mind are his tales of long, lonesome days and nights in the snowy emptiness of Northern Canada. Meditative days and nights spent in academic concentration. Not on the externals of advertising copy. Not on the by-products of advertising. But in deep, scholarly contemplation to isolate a fundamental concept of true advertising—which is copy.7

In a conversation some years later, Lasker elaborated on the theme: “He carried himself in a military way—spoke his words in a short, choppy manner. He impressed you as a man who had lived alone, and within himself, as a man there in those northern vastnesses would have to do . . . He was a typical lone-wolf type . . .”8

Much of this, it later turned out, was malarkey. Subsequent inquiries failed to turn up any “John E. Kennedy” among the ranks of the Mounties. Kennedy was Canadian by birth, but it appears that the closest he ever got to the “snowy emptiness of Northern Canada” was the Hudson’s Bay Company’s department store in Winnipeg, for which he wrote some undistinguished copy at the turn of the century. He subsequently bounced around—working on a Montreal newspaper, writing ads for a shoe company in Boston, and even promoting his own designs for shoes and clothing.9 He did some work for cereal-maker C.W. Post in 1903, although it is unclear whether he worked for Post directly, or through the Charles H. Fuller agency.10

Lasker was intrigued, in part because it emerged that the handsome stranger across the desk from him had written the ads for Dr. Shoop’s Restorative. Now he was all the more determined to learn Kennedy’s definition of advertising. When he pressed him, Kennedy countered by asking Lasker what his conception of advertising was.

“It is news,” Lasker replied.11

“No,” Kennedy said. “News is a technique of presentation, but advertising is a very simple thing. I can give it to you in three words.”

“Well,” Lasker exclaimed impatiently, “I am hungry! What are those three words?”

“Salesmanship in print,” Kennedy said.

A century later, this doesn’t sound like a particularly powerful insight. But to Lasker’s ears, it was a revelation. He knew about salesmanship: he was an excellent salesman. Advertising, Kennedy was telling him, was simply a stand-in for him when he wore his salesman’s hat. Great advertising did the same work as a great salesman. Advertising multiplied the work of the “salesman” who wrote it a thousand-fold. “The minute he told me that,” Lasker later recalled, “the very second he told me that, I understood it.”12 Finally, there was an idea on the table which Lasker could work with.

While Lasker was thinking through this insight, Kennedy dropped another thunderbolt: a letter to Lord & Thomas from Dr. Shoop. The letter stated that Kennedy was under contract to his patent-medicine firm for the balance of 1904 at an annual salary of $16,000—a staggering sum. (Lasker’s six copywriters were then commanding something like $1,400 a year for their full-time services.) Shoop wrote that both he and Kennedy wanted to end the arrangement, and proposed that if Lord & Thomas would take over the contract for the balance of the year—$8,000—he would contribute half of that sum, or $4,000.13

Lasker agreed to take the proposal to Ambrose Lord and Daniel Thomas the next day. He told Kennedy that he “couldn’t conceive” that they would turn him down.14 With a tentative deal struck, Lasker and Kennedy then continued their discussion until well past midnight.

Lasker guessed that Ambrose Thomas (whom he called a “Scotch Yankee”) would be astounded at the price tag, but unable to resist the 50 percent subsidy offered by Shoop. He was right: Thomas agreed to the deal, but on one condition—that he “never have to see the fellow.” During the subsequent two years, Thomas had almost no contact with the high-priced talent that Lasker had brought under his roof.15

As soon as Kennedy signed on, Lasker asked him for a tutorial in the theory of advertising. He confessed that he felt like “the fellow who uses electricity but doesn’t know what force it is. Sometimes he doesn’t get the right results; sometimes he does.”16 Kennedy agreed, and so for the next year, they did their respective jobs during the day—with Kennedy mostly writing at home—and met for “classes” after hours. Kennedy was uncomfortable speaking to groups, but he was a superb teacher one-on-one. No doubt it was gratifying to Kennedy’s considerable ego to have a brilliant student catering to him and hanging on his every word.

Somewhere along the line, the lessons turned into short essays written by Kennedy. The first essay defined advertising as “salesmanship in print.”17 The second focused on the application of this principle—a lesson that Kennedy called “Reason Why in Copy.” Advertisers, Kennedy wrote disapprovingly, seemed to believe consumers should buy their goods because it was good for the advertisers—and this arrogant attitude came through loud and clear in their copy. Nonsense, said Kennedy: advertisers had to give consumers a “reason why” they should buy the advertised goods.

Again, more than a hundred years after the fact, this sounds elementary. And it was far from a new idea: the patent-medicine vendors had for many years been concocting spurious reasons why consumers should purchase their dubious products. (One ad for Dr. Chase’s Recipe Book—an 1867 book aimed at “merchants, grocers, saloon-keepers, physicians, druggists, tanners, shoe makers, and harness makers,” among others—was titled “Reasons Why.”18) Like everyone else who had trained in the patent-medicine field, Kennedy understood that “medicines were worthless merchandise until a demand was created.”19 And reasons why created that demand. Lasker, who craved “the Big Idea,” felt that he was gaining profound insights into his trade, and this gave him newfound confidence.

That confidence came in handy when, not many months later, J. Walter Thompson—the legendary head of the New York agency that bore his name—demanded an audience with Lord & Thomas. Thompson had seen an article in Judicious Advertising, the Lord & Thomas house organ, celebrating the hiring of Kennedy at $16,000 per year, and felt the need to straighten out his Chicago-based competitors.

Thompson arrived at Lasker’s office, “white whiskered [and] fiercely mustachioed.”20 As a starstruck Lasker later recalled the encounter, Thompson delivered a stern lecture: “He said, ‘Young man, I have come out here with no interest for you, but because it happens that our interests are identical. I have got to give you good advice to save myself. What is all this foolishness that you are doing—paying $16,000 to a copywriter! Now, you are just going to ruin the line. There isn’t any copywriter born ever worth over $3,000!’”21

But Lasker, believing that he was on the right track, wasn’t intimidated. When he was with Kennedy, he felt he was “in the presence of a great man.” Yes, Kennedy was “eccentric, egocentric, utterly inconsiderate of everyone else”—and expensive—but he held the key for which Lasker had been searching. And history ultimately proved that Lasker’s faith in the power of copy was well placed. The J. Walter Thompson agency, as Lasker noted years later, was eventually taken over Stanley and Helen Resor, “than whom there have never been greater copywriters.”22

![]()

Sometime in the early summer of 1904, Lasker heard that the Nineteen Hundred Washer Company—a manufacturer of washing machines in Binghamton, New York, that sold exclusively by mail order—might be shopping for a new ad agency.23 Lasker and Kennedy sat down and analyzed the company’s recent campaigns.

Washers in that day were clumsy, hand-cranked machines—only slight improvements over tubs and washboards (some “washing machines,” in fact, were little more than tubs with washboards attached). Motorized machines were still several years in the future. Doing the family wash, therefore, was hard labor, requiring hours of exertion and leading to aching muscles and chapped hands. Monday was washday in many households—the origin of the phrase “Blue Monday.”

The main selling point of the Nineteen Hundred machine was a set of “perfectly adjusted ball-bearings” that supposedly minimized wear and tear on both the housewife and her family’s clothes. To Kennedy’s eye, the company’s ads were dreadful. They depicted a haggard-looking woman, hair askew, who appeared to be dragging a washing machine behind her, by means of an enormous chain attached to the small of her back. “Are you chained to the wash tub?” demanded the headline. “Whether a housekeeper does her own washing or not, the worry and work connected with ‘Blue Monday’ literally chain her to the wash tub. We can sever the chain.”

Kennedy ticked off the many failings of the concept. The chain metaphor was negative and would drive away any woman who didn’t want to think of herself as an oppressed drudge. The ad said almost nothing about what the Nineteen Hundred could do—it provided no reason why—and had no news interest. And finally, it offered the washer on an installment plan, of which most consumers were still highly suspicious. “Otherwise,” Kennedy sniffed, “it is all right.”24

Lasker and Kennedy talked their way through alternatives. Then they took a train to Binghamton, where Lasker successfully sold the account. During that trip, Lasker and Kennedy learned that Nineteen Hundred was “keying” its advertisements to different newspapers to show the response rates pulled by different ads in different areas. None of their current ads, company officials complained, were paying for themselves. If things didn’t turn around soon, they told the team from Lord & Thomas, Nineteen Hundred would be in trouble.

Back in Chicago, Kennedy struggled to come up with a new approach. Lasker, watching the master at work, discovered that writing did not come easily to Kennedy:

He had to think everything out laboriously, with labored pains. I imagine he corrected an advertisement . . . 25 to 50 times before he would release it. And to write his key ad, which is the first ad of the campaign, might take him a month or six weeks. . . .25

He would be lost to the world for two hours, thinking out a paragraph of 50 or 60 words. Then, laboriously, he would underline and scratch out until . . . maybe half or three-quarters of the words were taken out. He would hunt for the shading of a word, and then seek to polish the sentence so that its impact was not to be resisted.26

When Kennedy’s concept for the Nineteen Hundred finally arrived, it was brilliant. The new ad still featured a woman and a machine. This time, though, the woman sat in a rocking chair next to the washer. Her hair was perfectly arranged in a Sunday-go-to-meeting bun. Her face was serene—eyes closed, as if in prayer. Her right hand sat languidly on the machine’s crank. “Let this machine do your washing free,” read the headline. Then followed some thirty paragraphs of detailed description, in two parts. The first described how the machine actually worked—with “motor springs” and paddles doing all the hard work “in from six to ten minutes by the clock.” The second part attempted to rehabilitate the concept of installment-plan buying, arguing that having the housewife send 50 cents a week until the machine was paid for was actually less than “what the machine saves you every week.”

The ad was stiff and wordy by today’s standards. But the paragraphs and sentences were short and studded with the underlined and capitalized words that emerged as Kennedy’s trademarks. Reasons why abounded: Do twice the wash in half the time. Let our machine pay for itself. Use the washer four weeks at our expense. And a concluding note of urgency: “This offer may be withdrawn at any time it overcrowds our factory.”

Kennedy’s ad ran in selected publications for a total of $715. In the first seven days, it generated 1,547 inquiries, for a per-inquiry cost of 47 cents. The Nineteen Hundred Company, accustomed to paying upwards of $20 dollars per inquiry, was ecstatic. In addition, the quality of the inquiries was unprecedented. From the pile of more than 1,500 responses, the Nineteen Hundred Washer Company’s treasurer, R. L. Bieber pulled 200 at random. Of those, 119 asked the company to send a washer with no questions asked.

What did Lasker think of this coup, which increased his client’s business sixfold in four months, and more than validated his faith in the mysterious stranger from the North? “I had learned,” he said.27

One of the things that he learned from Kennedy—which the Canadian in turn had learned from his days in the patent-medicine trade—was the power of keyed advertising, which used coupons, unique return addresses, or other devices to track responses. It wasn’t enough simply to write what you thought was great copy; you had to test that copy to see if your instincts were right. Kennedy had enormous confidence in his abilities; nevertheless, he believed that talent and intuition weren’t enough. Put your best ideas out there, he argued, and then see what works.

Briefly, Lord & Thomas ran parallel ads for the Nineteen Hundred washers in the same magazines—one ad written by Kennedy, and one not—to see which pulled better. (On a cost-per-inquiry basis, Kennedy’s were five times as effective.) Kennedy welcomed this kind of scrutiny, and he and Lasker tried a similar approach with several other accounts. Using keyed ads, they experimented with different copy approaches and carefully tracked responses. Lasker began assembling what came to be called his “Record of Results.” The information contained in that wall of black filing cabinets served as the basis for training generations of copywriters.

Kennedy then began writing the first of a series of twelve short essays for publication in Judicious Advertising. The premise of the essays was that all advertising should be tested in these ways. Each article began with a fairly specific challenge—how to test mail-order advertising, for example—and offered ways to respond to that challenge. In most cases, the proposed solution involved pitting the advertiser’s current ads against “reason-why” advertising that would be prepared, naturally enough, by Lord & Thomas. At the end of each article came a pitch for the agency: “Let us talk the Saving process over together, in a personal interview.”28

This writing exercise proved to be more difficult than anticipated. Lasker believed that his resident genius could crank out a dozen essays on advertising with little difficulty. After all, wasn’t Kennedy the world’s leading expert on the subject? But Kennedy’s genius quickly ran dry. As one Lasker associate later commented: “I think he was to do twelve articles for Judicious Advertising. He wrote five of the twelve. He could find nothing new or any resourcefulness in his makeup to enable him to carry on.”29

It is unclear who wrote the remaining articles. What is clear, though, is that Lasker ultimately put them to very effective use. He gathered the articles together and published them in a pamphlet titled The Book of Advertising Tests. He then persuaded a number of friendly magazines and newspapers to donate space, which he used to advertise the availability of the pamphlet to anyone who was interested. The response, according to Lasker, was overwhelming: “In response to these advertisements, it was nothing for us to receive hundreds of letters a week from leading manufacturers all over the United States. I doubt if there were 10 percent of the big manufacturers and advertisers of America who didn’t write us at that time.”30

Like Lasker, America was hungry to learn more about advertising. Lasker used the outpouring of interest generated by The Book of Advertising Tests to change the Lord & Thomas client base:

I immediately switched our business . . . Kennedy and I agreed to get mail order business, and we got it to the extent of about 35 percent of our volume.

We kept a record of the results. Every week, the clients would send us the papers and how they paid, and every Tuesday morning we would go over how the papers were doing, and order repeat insertions or not, depending on how the paper paid out.

In other words, Lasker and Kennedy refined their craft on the client’s nickel, and delivered increasingly effective advertising to those clients. Lasker later referred to this early mail-order effort—which tracked the agency’s work for some three hundred accounts—as a “great laboratory,” and it was one of the foundations upon which Lasker’s genius as a business consultant was based.31

Ultimately, however, it proved to be a self-limiting experiment. After about six years, Lasker quietly shut down his laboratory. Mail order, he had decided, was like working summer stock—good practice, but only a warm-up. “The reward,” he concluded, “is on Broadway.”32

![]()

The flood of inquiries that resulted from The Book of Advertising Tests overwhelmed Lord & Thomas’s small copy department. The agency had offered itself up as an expert, and the world had responded eagerly—but Lasker couldn’t meet its demands.

Kennedy’s unpredictability heightened the challenge. When it came time to negotiate his contract for 1905, the gifted Canadian announced that he was willing to sell only three days a week of his time to Lord & Thomas, as he wanted to reserve the balance for freelance activities. Lasker took what he could get. He gave Kennedy a $4,000 raise—to $20,000—and then prorated that figure to $10,000 to reflect Kennedy’s half-time status. Somewhat astoundingly, Kennedy then began advertising his freelance services in Judicious Advertising:

After January 1st, half my time is my own. The other half belongs to Lord & Thomas, Chicago. I am reserving half my time to write Copy for a few advertisers who are willing to pay for Results.33

Kennedy’s half-time status put a strain on the copywriting department, which was compounded by Lasker’s awareness that he should get out of the writing end of the business. He knew that his strengths lay in editing rather than writing.34 He had assessed his copywriting skills, as compared with Kennedy’s, and decided that he wasn’t good enough.

Still another factor squeezed the agency’s copywriting resources: the creation in 1905 of the “Outdoor Advertising Department.” This specialized group sold ad space inside streetcars, on billboards along streetcar lines, and on the main roads traversed by carriages. Although this was primarily a selling effort—approximately a dozen men sold these ads from offices in New York and Chicago—there was still writing involved, and the new department put even more pressure on Lasker’s small staff of writers.

So Lasker approached Ambrose Thomas with yet another bold request: to expand the copywriting department:

I said, “I have been upstairs and I have measured that we can take out all the files against the north windows and all the files against half of the west windows, and we can make nine offices eight by ten each. I want you to let me put up nine offices that will cost about $2,000 to build the partitions, and advertise for nine young newspaper men, and Kennedy and I will start training them, because out of the nine we might only get three or four.”35

Although Thomas remained skeptical of the power of advertising copy, he couldn’t deny the business generated by Lasker and Kennedy. They discussed the price tag associated with this daring new venture—primarily the additional copywriters—and Lasker came up with an estimate of up to $5,000 a head.36 Thomas gave his blessing, and Lasker set out to recruit his copywriters.

In subsequent recountings of this episode, he often claimed that Lord & Thomas was the first agency to set up a copywriting department, but this was another case of Lasker’s enthusiasm overwhelming the facts. N. W. Ayer established its “Copy Department” in 1900, a few years before Lasker built up his expanded staff.37 Cincinnati-based Procter & Collier began claiming in 1896 that it had copywriting “specialists” on its payroll.38 But at this early date, the top agencies were only dipping their toes in the copywriting waters. Even at the end of the decade, Ayer was cautioning against the industry’s “tendency toward copy exaltation.”39 Lasker felt no such reticence, and pursued his vision with a particular ferocity. By 1906, Lord & Thomas had nine copywriters—nominally headed by Kennedy, but directed by Lasker. Because Kennedy was awkward in front of even small groups, Lasker conveyed the master’s insights to them. “We had a class at least twice a week, for three or four years,” Lasker later recalled, “and the sessions would last four or five hours at a stretch.”40

The department was the “sensation of the advertising world,” Lasker boasted. But from the inside, it often looked less than sensational. Kennedy’s inability to work with groups hampered Lasker, who had account-servicing responsibilities that often took him out of town. Not surprisingly, the department’s output sometimes proved unsatisfactory. There was no easy way to replicate the Kennedy magic. “It was less easy than I anticipated,” Lasker admitted, “to implant the genius of Kennedy in other brains . . . Whenever Kennedy did it, it was perfect, but where the other nine men tried, we failed, nine times out of ten, and they failed ridiculously. It was one thing to have a technique, and another thing to learn the application.”41

Turnover was high, and having high-priced talent coming and going resulted in a lot of stomach-churning for Lasker. Too often, the best of these young people were stolen by competitors who offered them up to five times their Lord & Thomas salary. Meanwhile, of course, the bad ones—the ones who “failed ridiculously”—had to be let go. That job fell to Lasker, who despite his energy and brashness hated confrontation. “It made a terrible strain on me,” Lasker later admitted.42

A related strain was riding herd on his resident genius: “I had been working overwhelmingly, establishing this copy department. And this man Kennedy! If I had nothing else, just managing him was a man-breaking job, because you just had to sit on top of him to get the work out. He had very long lapses when he couldn’t work at all.”43

Kennedy turned out to be a basketful of contradictions. On first blush appearing to be an extrovert, he was in fact bashful, sensitive, and introverted—“hard to know, hard to talk to,” according to Lasker.44 Lord & Thomas’s half-time genius lived a life of extremely productive highs and miserably lows. He lost interest in accounts almost as soon as he had solved their initial challenge, leaving Lasker to struggle with the client, whose expectations now had been elevated by Kennedy’s talent. “He was like a bee,” Lasker complained. “He went and sipped the pollen out of a flower, and if he got it, his interest was gone. He wanted to try another flower.”45

As with many aspects of the Lasker story, alcohol played a prominent role. Kennedy was “pickled in liquor,” Lasker recalled—a “champion drinker.”46 He would work almost nonstop several days running, then disappear on a binge for weeks on end. Caring little about money but enamored of sailboats and other expensive luxuries, Kennedy often required advances even on his princely salary.

Alcohol fueled Kennedy’s eccentricities. One time, Lasker went looking for his troubled and inebriated genius, finally tracking him down at a shooting gallery on South State Street. Kennedy agreed to return to work, but first insisted on demonstrating his sharpshooting prowess to his boss. Right-handed, he hefted a rifle in his left hand, turned one eye away from the metal pigeon targets that were rolling by on a track—and picked off every one of them.47

Finally, Kennedy was suspicious and paranoid—“a man whom it was impossible to get along with,” as Lasker put it. In fact, Lasker believed that he was the only person who ever got along with Kennedy. “But that was my business—to get along with him,” added Lasker. “And it was worth the price to me.”48

The price eventually became too high. When Lasker most needed a reliable ally, bulwark, and stand-in, Kennedy proved to be fundamentally unreliable. He “couldn’t be managed,” Lasker concluded. Sometime in 1906, Kennedy and Lord & Thomas parted company. Given the enormous impact Kennedy had had on Lasker, it is remarkable how little time he actually spent at the firm. He arrived in Chicago in mid-1904, cut himself back to half-time in 1905, and left in 1906 to take a position with the advertising firm of Ethridge-Kennedy in New York.

The parting appears to have been reasonably amicable. When Lasker opened a Lord & Thomas office in New York in 1910, Kennedy rejoined the payroll there—a “re-recruitment” coup that Lasker later boasted about. But Lasker sensed that Kennedy had peaked and the magic was gone: “He had one big message to give, and from the day he left, he retrogressed steadily. He had done his big work. It is like some animals you read about who reproduce themselves . . . and then lie down and die.”49

Kennedy, Lasker concluded, was not a “born advertising man.” That was one reason why he had to work so hard at his copywriting. Of course, not being born into the business gave Kennedy advantages, as well. It forced him to articulate the business for himself and, by extension, for Lasker, Lord & Thomas, and the larger advertising community. It fell to others to extend Kennedy’s powerful concepts, and put them to their fullest use.

Kennedy eventually relocated to Los Angeles, where he became involved in real estate. He died in 1926, long forgotten by most people in the advertising industry. But he was not forgotten by Lasker, who for the rest of his life referred to Kennedy as the “father of modern advertising”—a title that he could reasonably have claimed for himself.