Successful Change and the Force That Drives It

People who have been through difficult, painful, and not very successful change efforts often end up drawing both pessimistic and angry conclusions. They become suspicious of the motives of those pushing for transformation; they worry that major change is not possible without carnage; they fear that the boss is a monster or that much of the management is incompetent. After watching dozens of efforts to enhance organizational performance via restructuring, reengineering, quality programs, mergers and acquisitions, cultural renewal, downsizing, and strategic redirection, I draw a different conclusion. Available evidence shows that most public and private organizations can be significantly improved, at an acceptable cost, but that we often make terrible mistakes when we try because history has simply not prepared us for transformational challenges.

The Globalization of Markets and Competition

People of my generation or older did not grow up in an era when transformation was common. With less global competition and a slower-moving business environment, the norm back then was stability and the ruling motto was: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” Change occurred incrementally and infrequently. If you had told a typical group of managers in 1960 that businesspeople today, over the course of eighteen to thirty-six months, would be trying to increase productivity by 20 to 50 percent, improve quality by 30 to 100 percent, and reduce new-product development times by 30 to 80 percent, they would have laughed at you. That magnitude of change in that short a period of time would have been too far removed from their personal experience to be credible.

The challenges we now face are different. A globalized economy is creating both more hazards and more opportunities for everyone, forcing firms to make dramatic improvements not only to compete and prosper but also to merely survive. Globalization, in turn, is being driven by a broad and powerful set of forces associated with technological change, international economic integration, domestic market maturation within the more developed countries, and the collapse of worldwide communism. (See figure 2–1.)

No one is immune to these forces. Even companies that sell only in small geographic regions can feel the impact of globalization. The influence route is sometimes indirect: Toyota beats GM, GM lays off employees, belt-tightening employees demand cheaper services from the corner dry cleaner. In a similar way, school systems, hospitals, charities, and government agencies are being forced to try to improve. The problem is that most managers have no history or legacy to guide them through all this.

Given the track record of many companies over the past two decades, some people have concluded that organizations are simply unable to change much and that we must learn to accept that fact. But this assessment cannot account for any of the dramatic transformation success stories from the recent past. Some organizations have discovered how to make new strategies, acquisitions, reengineering, quality programs, and restructuring work wonderfully well for them. They have minimized the change errors described in chapter 1. In the process, they have been saved from bankruptcy, or gone from middle-of-the-pack players to industry leaders, or pulled farther out in front of their closest rivals.

FIGURE 2-1

Economic and social forces driving the need for major change in organizations

Source: From The New Rules: How to Succeed in Today’s Post-Corporate World by John P. Kotter. Copyright © 1995 by John P. Kotter. Adapted with permission of The Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster.

An examination of these success stories reveals two important patterns. First, useful change tends to be associated with a multistep process that creates power and motivation sufficient to overwhelm all the sources of inertia. Second, this process is never employed effectively unless it is driven by high-quality leadership, not just excellent management—an important distinction that will come up repeatedly as we talk about instituting significant organizational change.

The Eight-Stage Change Process

The methods used in successful transformations are all based on one fundamental insight: that major change will not happen easily for a long list of reasons. Even if an objective observer can clearly see that costs are too high, or products are not good enough, or shifting customer requirements are not being adequately addressed, needed change can still stall because of inwardly focused cultures, paralyzing bureaucracy, parochial politics, a low level of trust, lack of teamwork, arrogant attitudes, a lack of leadership in middle management, and the general human fear of the unknown. To be effective, a method designed to alter strategies, reengineer processes, or improve quality must address these barriers and address them well.

All diagrams tend to oversimplify reality. I therefore offer figure 2–2 with some trepidation. It summarizes the steps producing successful change of any magnitude in organizations. The process has eight stages, each of which is associated with one of the eight fundamental errors that undermine transformation efforts. The steps are: establishing a sense of urgency, creating the guiding coalition, developing a vision and strategy, communicating the change vision, empowering a broad base of people to take action, generating short-term wins, consolidating gains and producing even more change, and institutionalizing new approaches in the culture.

FIGURE 2-2

The eight-stage process of creating major change

Source: Adapted from John P. Kotter, “Why Transformation Efforts Fail,” Harvard Business Review (March–April 1995): 61. Reprinted with permission.

The first four steps in the transformation process help defrost a hardened status quo. If change were easy, you wouldn’t need all that effort. Phases five to seven then introduce many new practices. The last stage grounds the changes in the corporate culture and helps make them stick.

People under pressure to show results will often try to skip phases—sometimes quite a few—in a major change effort. A smart and capable executive recently told me that his attempts to introduce a reorganization were being blocked by most of his management team. Our conversation, in short form, was this:

“Do your people believe the status quo is unacceptable?” I asked. “Do they really feel a sense of urgency?”

“Some do. But many probably do not.”

“Who is pushing for this change?”

“I suppose it’s mostly me,” he acknowledged.

“Do you have a compelling vision of the future and strategies for getting there that help explain why this reorganization is necessary?”

“I think so,” he said, “although I’m not sure how clear it is.”

“Have you ever tried to write down the vision and strategies in summary form on a few pages of paper?”

“Not really.”

“Do your managers understand and believe in that vision?”

“I think the three or four key players are on board,” he said, then conceded, “but I wouldn’t be surprised if many others either don’t understand the concept or don’t entirely believe in it.”

In the language system of the model shown in figure 2–2, this executive had jumped immediately to phase 5 in the transformation process with his idea of a reorganization. But because he mostly skipped the earlier steps, he ran into a wall of resistance. Had he crammed the new structure down people’s throats, which he could have done, they would have found a million clever ways to undermine the kinds of behavioral changes he wanted. He knew this to be true, so he sat in a frustrated stalemate. His story is not unusual.

People often try to transform organizations by undertaking only steps 5, 6, and 7, especially if it appears that a single decision—to reorganize, make an acquisition, or lay people off—will produce most of the needed change. Or they race through steps without ever finishing the job. Or they fail to reinforce earlier stages as they move on, and as a result the sense of urgency dissipates or the guiding coalition breaks up. Truth is, when you neglect any of the warm-up, or defrosting, activities (steps 1 to 4), you rarely establish a solid enough base on which to proceed. And without the follow-through that takes place in step 8, you never get to the finish line and make the changes stick.

The Importance of Sequence

Successful change of any magnitude goes through all eight stages, usually in the sequence shown in figure 2–2. Although one normally operates in multiple phases at once, skipping even a single step or getting too far ahead without a solid base almost always creates problems.

I recently asked the top twelve officers in a division of a large manufacturing firm to assess where they were in their change process. They judged that they were about 80 percent finished with stage #1, 40 percent with #2, 70 percent with #3, 60 percent with #4, 40 percent with #5, 10 percent with #6, and 5 percent with #7 and #8. They also said that their progress, which had gone well for eighteen months, was now slowing down, leaving them increasingly frustrated. I asked what they thought the problem was. After much discussion, they kept coming back to “corporate headquarters.” Key individuals at corporate, including the CEO, were not sufficiently a part of the guiding coalition, which is why the twelve division officers judged that only 40 percent of the work in #2 was done. Because higher-order principles had not been decided, they found it nearly impossible to settle on the more detailed strategies in #3. Their communication of the vision (#4) was being undercut, they believed, by messages from corporate that employees interpreted as being inconsistent with their new direction. In a similar way, empowerment efforts (#5) were being sabotaged. Without a clearer vision, it was hard to target credible short-term wins (#6). By moving on and not sufficiently confronting the stage 2 problem, they made the illusion of progress for a while. But without the solid base, the whole effort eventually began to teeter.

Normally, people skip steps because they are feeling pressures to produce. They also invent new sequences because some seemingly reasonable logic dictates such a choice. After getting well into the urgency phase (#1), all change efforts end up operating in multiple stages at once, but initiating action in any order other than that shown in figure 2–2 rarely works well. It doesn’t build and develop in a natural way. It comes across as contrived, forced, or mechanistic. It doesn’t create the momentum needed to overcome enormously powerful sources of inertia.

Projects within Projects

Most major change initiatives are made up of a number of smaller projects that also tend to go through the multistep process. So at any one time, you might be halfway through the overall effort, finished with a few of the smaller pieces, and just beginning other projects. The net effect is like wheels within wheels.

A typical example for a medium-to-large telecommunications company: The overall effort, designed to significantly increase the firm’s competitive position, took six years. By the third year, the transformation was centered in steps 5, 6, and 7. One relatively small reengineering project was nearing the end of stage 8. A restructuring of corporate staff groups was just beginning, with most of the effort in steps 1 and 2. A quality program was moving along, but behind schedule, while a few small final initiatives hadn’t been launched yet. Early results were visible at six to twelve months, but the biggest payoff didn’t come until near the end of the overall effort.

When an organization is in a crisis, the first change project within a larger change process is often the save-the-ship or turnaround effort. For six to twenty-four months, people take decisive actions to stop negative cash flow and keep the organization alive. The second change project might be associated with a new strategy or reengineering. That could be followed by major structural and cultural change. Each of these efforts goes through all eight steps in the change sequence, and each plays a role in the overall transformation.

Because we are talking about multiple steps and multiple projects, the end result is often complex, dynamic, messy, and scary. At the beginning, those who attempt to create major change with simple, linear, analytical processes almost always fail. The point is not that analysis is unhelpful. Careful thinking is always essential, but there is a lot more involved here than (a) gathering data, (b) identifying options, (c) analyzing, and (d) choosing.

Q: So why would an intelligent person rely too much on simple, linear, analytical processes?

A: Because he or she has been taught to manage but not to lead.

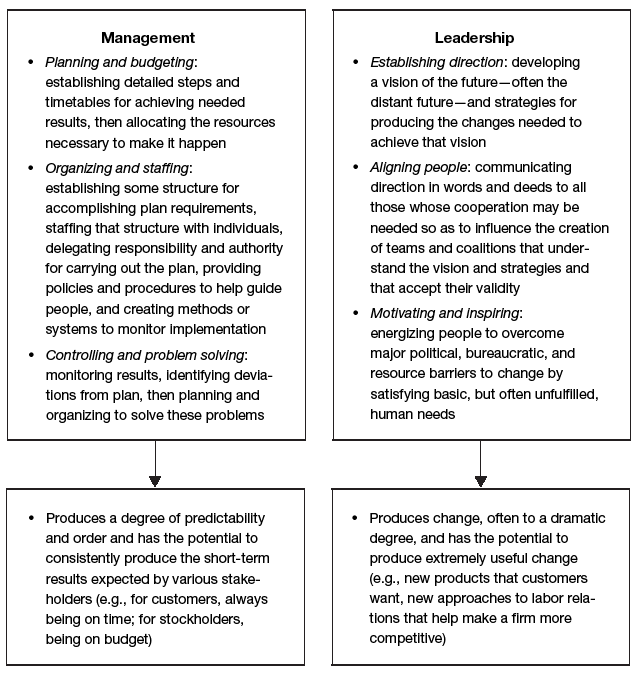

Management versus Leadership

Management is a set of processes that can keep a complicated system of people and technology running smoothly. The most important aspects of management include planning, budgeting, organizing, staffing, controlling, and problem solving. Leadership is a set of processes that creates organizations in the first place or adapts them to significantly changing circumstances. Leadership defines what the future should look like, aligns people with that vision, and inspires them to make it happen despite the obstacles (see figure 2–3). This distinction is absolutely crucial for our purposes here: A close look at figures 2–2 and 2–3 shows that successful transformation is 70 to 90 percent leadership and only 10 to 30 percent management. Yet for historical reasons, many organizations today don’t have much leadership. And almost everyone thinks about the problem here as one of managing change.

For most of this century, as we created thousands and thousands of large organizations for the first time in human history, we didn’t have enough good managers to keep all those bureaucracies functioning. So many companies and universities developed management programs, and hundreds and thousands of people were encouraged to learn management on the job. And they did. But people were taught little about leadership. To some degree, management was emphasized because it’s easier to teach than leadership. But even more so, management was the main item on the twentieth-century agenda because that’s what was needed. For every entrepreneur or business builder who was a leader, we needed hundreds of managers to run their ever-growing enterprises.

FIGURE 2-3

Management versus leadership

Source: From A Force for Change: How Leadership Differs from Management by John P. Kotter. Copyright © 1990 by John P. Kotter. Adapted with permission of The Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster.

Unfortunately for us today, this emphasis on management has often been institutionalized in corporate cultures that discourage employees from learning how to lead. Ironically, past success is usually the key ingredient in producing this outcome. The syndrome, as I have observed it on many occasions, goes like this: Success creates some degree of market dominance, which in turn produces much growth. After a while, keeping the ever-larger organization under control becomes the primary challenge. So attention turns inward, and managerial competencies are nurtured. With a strong emphasis on management but not leadership, bureaucracy and an inward focus take over. But with continued success, the result mostly of market dominance, the problem often goes unaddressed and an unhealthy arrogance begins to evolve. All of these characteristics then make any transformation effort much more difficult. (See figure 2–4.)

Arrogant managers can overevaluate their current performance and competitive position, listen poorly, and learn slowly. Inwardly focused employees can have difficulty seeing the very forces that present threats and opportunities. Bureaucratic cultures can smother those who want to respond to shifting conditions. And the lack of leadership leaves no force inside these organizations to break out of the morass.

The combination of cultures that resist change and managers who have not been taught how to create change is lethal. The errors described in chapter 1 are almost inevitable under these conditions. Sources of complacency are rarely attacked adequately because urgency is not an issue for people who have been asked all their lives merely to maintain the current system like a softly humming Swiss watch. A powerful enough guiding coalition with sufficient leadership is not created by people who have been taught to think in terms of hierarchy and management. Visions and strategies are not formulated by individuals who have learned only to deal with plans and budgets. Sufficient time and energy are never invested in communicating a new sense of direction to enough people—not surprising in light of a history of simply handing direct reports the latest plan. Structures, systems, lack of training, or supervisors are allowed to disempower employees who want to help implement the vision—predictable, given how little most managers have learned about empowerment. Victory is declared much too soon by people who have been instructed to think in terms of system cycle times: hours, days, or weeks, not years. And new approaches are seldom anchored in the organization’s culture by people who have been taught to think in terms of formal structure, not culture. As a result, expensive acquisitions produce none of the hoped-for synergies, dramatic downsizings fail to get costs under control, huge reengineering projects take too long and provide too little benefit, and bold new strategies are never implemented well.

FIGURE 2-4

The creation of an overmanaged, underled corporate culture

Source: From Corporate Culture and Performance by John P. Kotter and James L. Heskett. Copyright © 1992 by Kotter Associates, Inc. and James L. Heskett. Adapted with permission of The Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster.

Employees in large, older firms often have difficulty getting a transformation process started because of the lack of leadership coupled with arrogance, insularity, and bureaucracy. In those organizations, where a change program is likely to be overmanaged and underled, there is a lot more pushing than pulling. Someone puts together a plan, hands it to people, and then tries to hold them accountable. Or someone makes a decision and demands that others accept it. The problem with this approach is that it is enormously difficult to enact by sheer force the big changes often needed today to make organizations perform better. Transformation requires sacrifice, dedication, and creativity, none of which usually comes with coercion.

Efforts to effect change that are overmanaged and underled also tend to try to eliminate the inherent messiness of transformations. Eight stages are reduced to three. Seven projects are consolidated into two. Instead of involving hundreds or thousands of people, the initiative is handled mostly by a small group. The net result is almost always very disappointing.

Managing change is important. Without competent management, the transformation process can get out of control. But for most organizations, the much bigger challenge is leading change. Only leadership can blast through the many sources of corporate inertia. Only leadership can motivate the actions needed to alter behavior in any significant way. Only leadership can get change to stick by anchoring it in the very culture of an organization.

As you’ll see in the next few chapters, this leadership often begins with just one or two people. But in anything but the very smallest of organizations, that number needs to grow and grow over time. The solution to the change problem is not one larger-than-life individual who charms thousands into being obedient followers. Modern organizations are far too complex to be transformed by a single giant. Many people need to help with the leadership task, not by attempting to imitate the likes of Winston Churchill or Martin Luther King, Jr., but by modestly assisting with the leadership agenda in their spheres of activity.

The Future

The change problem inside organizations would become less worrisome if the business environment would soon stabilize or at least slow down. But most credible evidence suggests the opposite: that the rate of environmental movement will increase and that the pressures on organizations to transform themselves will grow over the next few decades. If that’s the case, the only rational solution is to learn more about what creates successful change and to pass that knowledge on to increasingly larger groups of people.

From what I have seen over the past two decades, helping individuals to better understand transformation has two components, both of which will be addressed in some detail in the remainder of this book. The first relates to the various steps in the multistage process. Most of us still have plenty to learn about what works, what doesn’t, what is the natural sequence of events, and where even very capable people have difficulties. The second component is associated with the driving force behind the process: leadership, leadership, and still more leadership.

If you sincerely think that you and other relevant people in your organization already know most of what is necessary to produce needed change and, therefore, are quite logically wondering why you should take the time to read the rest of this book, let me suggest that you consider the following. What do you think we would find if we searched all the documents produced in your organization in the last twelve months while looking for two phrases: “managing change” and “leading change”? We would look at memos, meeting summaries, newsletters, annual reports, project reports, formal plans, etc. Then we would turn the numbers into percentages—X percent of the references are to “managing change” and Y percent to “leading change.”

Of course the findings from this exercise could be nothing more than meaningless semantics. But then again, maybe they would accurately reflect the way your organization thinks about change. And maybe that has something to do with how quickly you improve the quality of products or services, increase productivity, lower costs, and innovate.