Creating the Guiding Coalition

Major transformations are often associated with one highly visible individual. Consider Chrysler’s comeback from near bankruptcy in the early 1980s, and we think of Lee Iacocca. Mention Wal-Mart’s ascension from small-fry to industry leader, and Sam Walton comes to mind. Read about IBM’s efforts to renew itself, and the story centers around Lou Gerstner. After a while, one might easily conclude that the kind of leadership that is so critical to any change can come only from a single larger-than-life person.

This is a very dangerous belief.

Because major change is so difficult to accomplish, a powerful force is required to sustain the process. No one individual, even a monarch-like CEO, is ever able to develop the right vision, communicate it to large numbers of people, eliminate all the key obstacles, generate short-term wins, lead and manage dozens of change projects, and anchor new approaches deep in the organization’s culture. Weak committees are even worse. A strong guiding coalition is always needed—one with the right composition, level of trust, and shared objective. Building such a team is always an essential part of the early stages of any effort to restructure, reengineer, or retool a set of strategies.

Going It Alone: The Isolated CEO

The food company in this case had an economic track record between 1975 and 1990 that was extraordinary. Then the industry changed, and the firm stumbled badly.

The CEO was a remarkable individual. Being 20 percent leader, 40 percent manager, and the rest financial genius, he had guided his company successfully by making shrewd acquisitions and running a tight ship. When his industry changed in the late 1980s, he tried to transform the firm to cope with the new conditions. And he did so with the same style he had been using for fifteen years—that of a monarch, with advisors.

“King” Henry had an executive committee, but it was an information-gathering/dispensing group, not a decision-making body. The real work was done outside the meetings. Henry would think about an issue alone in his office. He would then share an idea with Charlotte and listen to her comments. He would have lunch with Frank and ask him a few questions. He would play golf with Ari and note his reaction to an idea. Eventually, the CEO would make a decision by himself. Then, depending on the nature of the decision, he would announce it at an executive committee meeting or, if the matter was somehow sensitive, tell his staff one at a time in his office. They in turn would pass the information on to others as needed.

This process worked remarkably well between 1975 and 1990 for at least four reasons: (1) the pace of change in Henry’s markets was not very fast, (2) he knew the industry well, (3) his company had such a strong position that being late or wrong on any one decision was not that risky, and (4) Henry was one smart fellow.

And then the industry changed.

For four years, until his retirement in 1994, Henry tried to lead a transformation effort using the same process that had served him so well for so long. But this time the approach did not work because both the number and the nature of the decisions being made were different in some important ways.

Prior to 1990, the issues were on average smaller, less complex, less emotionally charged, and less numerous. A smart person, using the one-on-one discussion format, could make good decisions and have them implemented. With the industry in flux and the need for major change inside the firm, the issues suddenly came faster and bigger. One person, even an exceptionally capable individual, could no longer handle this decision stream well. Choices were made and communicated too slowly. Choices were made without a full understanding of the issues. Employees were asked to make sacrifices without a clear sense of why they should do so.

After two years, objective evidence suggested that Henry’s approach wasn’t working. Instead of changing, he became more isolated and pushed harder. One questionable acquisition and a bitter layoff later, he reluctantly retired (with more than a small push from his board).

Running on Empty: The Low-Credibility Committee

This second scenario I have probably seen two dozen times. The biggest champion of change is the human resource executive, the quality officer, or the head of strategic planning. Someone talks the boss into putting this staff officer in charge of a task force that includes people from a number of departments and an outside consultant or two. The group may include an up-and-coming leader in the organization, but it does not have the top three or four individuals in the executive pecking order. And out of the top fifteen officers, only two to four are members.

Because the group has an enthusiastic head, the task force makes progress for a while. But all of the political animals both on and off this committee figure out quickly that it has little chance of long-term success, and thus limit their assistance, involvement, and commitment. Because everyone on the task force is busy, and because some are not convinced this is the best use of their time, scheduling enough meetings to create a shared diagnosis of the firm’s problems and to build trust among the group’s members becomes impossible. Nevertheless, the leader of the committee refuses to give up and struggles to make visible progress, often because of an enormous sense of dedication to the firm or its employees.

After a while, the work is done by a subgroup of three or four—mostly the chair, a consultant, and a Young Turk. The rest of the members rubber-stamp the ideas this small group produces, but they neither contribute much nor feel any commitment to the process. Sooner or later the problem becomes visible: when the group can’t get a consensus on key recommendations, when its committee recommendations fall on deaf ears, or when it tries to implement an idea and runs into a wall of passive resistance. With much hard work, the committee does make a few contributions, but they come only slowly and incrementally.

A postmortem of the affair shows that the task force never had a chance of becoming a functioning team of powerful people who shared a sense of problems, opportunities, and commitment to change. From the outset, the group never had the credibility necessary to provide strong leadership. Without that credibility, you have the equivalent of an eighteen-wheeler truck being propelled by a lawn mower engine.

Meanwhile, as this approach fails, the company’s competitive position gets a little weaker and the industry leader gets a little farther ahead.

Keeping Pace with Change: The Team

The central issue in both of these scenarios is that neither firm is taking into account the speed of market and technological change. In a less competitive and slower-moving world, weak committees can help organizations adapt at an acceptable rate. A committee makes recommendations. Key line managers reject most of the ideas. The group offers additional suggestions. The line moves another inch. The committee tries again. When both competition and technological change are limited, this approach can work. But in a faster-moving world, the weak committee always fails.

In a slow-moving world, a lone-ranger boss can make needed changes by talking to Charlotte, then Frank, then Ari and reflecting on what they say. He can go back to each of them for more information. After making a decision, he can communicate it to Charlotte, Frank, and Ari. Information processing is sequential and orderly. As long as the boss is capable and time is available, the process can work well. In a faster-moving world, this ponderous linear activity breaks down. It is too slow. It is not well enough informed with realtime information. And it makes implementation more difficult.

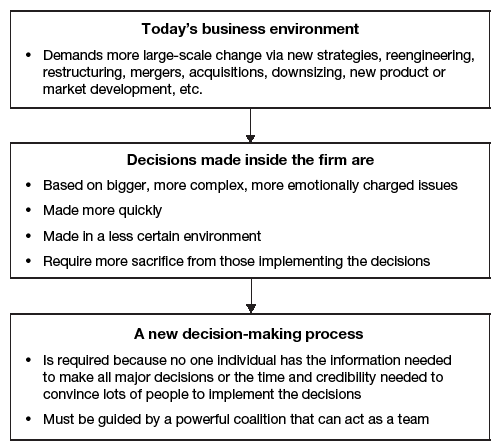

Today’s business environment clearly demands a new process of decision making (see figure 4–1). In a rapidly moving world, individuals and weak committees rarely have all the information needed to make good nonroutine decisions. Nor do they seem to have the credibility or the time required to convince others to make the personal sacrifices called for in implementing changes. Only teams with the right composition and sufficient trust among members can be highly effective under these new circumstances. This new truism applies equally well to a guiding change coalition on the factory floor, in the new-product development process, or at the very top of an organization during a major transformation effort. A guiding coalition that operates as an effective team can process more information, more quickly. It can also speed the implementation of new approaches because powerful people are truly informed and committed to key decisions.

FIGURE 4-1

Decision making in today’s business environment

So why don’t managers use teams more often to help produce change? To some degree, a conflict of interest is involved. Teams aren’t promoted, individuals are, and individuals need unambiguous track records to advance their careers. The argument “I was on a team that. . .” doesn’t sell well in most places today.

But to an even greater degree, the problem is related to history. Most senior-level executives were raised managerially in an era when teamwork was not essential. They may have talked “team” and used sports metaphors, but the reality was hierarchical—typically, a boss and his eight direct reports. Having seen many examples of poorly functioning committees, where everything moves slower instead of faster, they are often much more comfortable in sticking with the old format, even if it is working less and less well over time.

The net result: In a lot of reengineering and restrategizing efforts, people simply skip this step or give it minimum attention. They then race ahead to try to create the vision, or downsize the organization, or whatever. But sooner or later, the lack of a strong team to guide the effort proves fatal.

Putting Together the Guiding Coalition

The first step in putting together the kind of team that can direct a change effort is to find the right membership. Four key characteristics seem to be essential to effective guiding coalitions. They are:

1. POSITION POWER: Are enough key players on board, especially the main line managers, so that those left out cannot easily block progress?

2. EXPERTISE: Are the various points of view—in terms of discipline, work experience, nationality, etc.—relevant to the task at hand adequately represented so that informed, intelligent decisions will be made?

3. CREDIBILITY: Does the group have enough people with good reputations in the firm so that its pronouncements will be taken seriously by other employees?

4. LEADERSHIP: Does the group include enough proven leaders to be able to drive the change process?

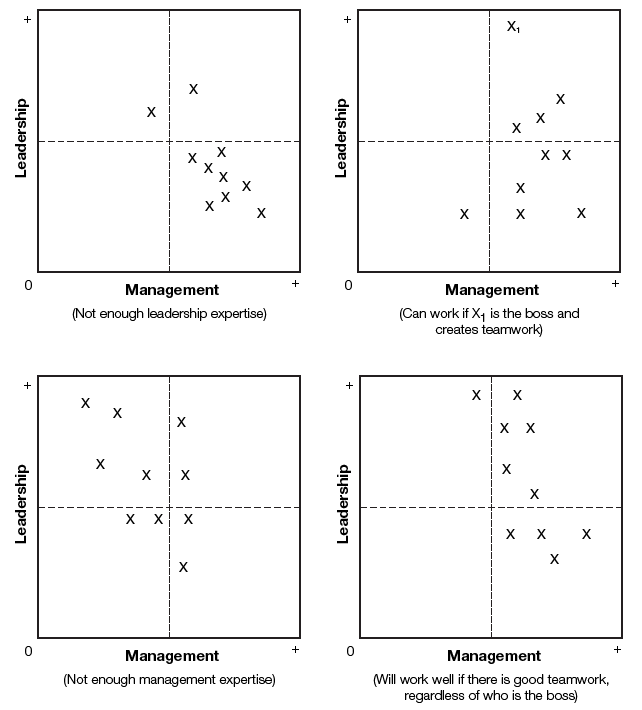

This last concern, about leadership, is particularly important. You need both management and leadership skills on the guiding coalition, and they must work in tandem, teamwork style. The former keeps the whole process under control, while the latter drives the change. (The grids in figure 4–2 depict various combinations of leadership and management that may or may not work.)

FIGURE 4-2

Profiles of four different guilding coalitions

A guiding coalition with good managers but poor leaders will not succeed. A managerial mindset will develop plans, not vision; it will vastly undercommunicate the need for and direction of change; and it will control rather than empower people. Yet companies with much historical success are often left with corporate cultures that create just that mindset that rejects both leaders and leadership. Ironically, great success creates a momentum that demands more and more managers to keep the growing enterprise under control while requiring little if any leadership. In such firms, much care needs to be exercised or the guiding coalition will lack this critical element.

Missing leadership is generally addressed in three ways: (1) people are brought in from outside the firm, (2) employees who know how to lead are promoted from within, or (3) employees who hold positions requiring leadership, but who rarely lead, are encouraged to accept the challenge. Whatever the method chosen to get there, the end result—a team with leadership skills—must be the same. Never forget: A guiding coalition made up only of managers—even superb managers who are wonderful people—will cause major change efforts to fail.

The size of an effective coalition seems to be related to the size of the organization. Change often starts with just two or three people. The group in successful transformations then grows to half a dozen in relatively small firms or in small units of larger firms. In bigger enterprises, twenty to fifty may eventually need to be signed up.

Qualities to Avoid—or Manage Carefully

Two types of individuals should be avoided at all costs when putting together a guiding coalition. The first have egos that fill up a room, leaving no space for anybody else. The second are what I call snakes, people who create enough mistrust to kill teamwork.

At senior levels in most organizations, people have large egos. But unless they also have a realistic sense of their weaknesses and limitations, unless they can appreciate complementary strengths in others, and unless they can subjugate their immediate interests to some greater goal, they will probably contribute about as much to a guiding coalition as does nuclear waste. If such a person is the central player in the coalition, you can usually kiss teamwork and a dramatic transformation good-bye.

Snakes are equally disastrous, although in a different way. They damage the trust that is always an essential ingredient in teamwork. A snake is an expert at telling Sally something about Fred and Fred something about Sally that undermines Sally and Fred’s relationship.

Snakes and big egos can be extremely intelligent, motivated, and productive in certain ways. As such, they can get promoted to senior management positions and be logical candidates for a guiding coalition. Smart change agents seem to be skilled at spotting these people and keeping them off the team. If that’s impossible, capable leaders watch and manage these folks very carefully.

Another type of individual to at least be wary of is the reluctant player. In organizations with extremely high urgency rates, getting people to sign on to a change coalition is easy. But since high urgency is rare, more effort is often required, especially for a few key people who have no interest in signing on.

Jerry is an overworked division-level CFO in a major oil company. Conservative by nature, he is more manager than leader and is naturally suspicious of calls for significant change because of the potential disruption and risk. But after having performed well at his corporation for thirty-five years, Jerry is too powerful and too respected to be ignored. Consequently, his division head has devoted hours over a period of two months attempting to convince him that major change is necessary and that Jerry’s active involvement is essential. Halfway through the courtship, the CFO still makes excuses, citing his lack of both time and qualifications to help. But persistence pays off, and Jerry eventually signs up.

It can be tempting to write off people like Jerry and try to work around them. But if such individuals are central players with a lot of authority or credibility, this tactic rarely works well. Very often the problem with signing up a Jerry goes back to urgency. He doesn’t see the problems and opportunities very clearly, and the same holds for the people with whom he interacts on a daily basis. With complacency high, you’ll never convince him to give the time and effort needed to create a winning coalition.

When people like Jerry have the qualities of a snake or big ego, a negotiated resignation or retirement is often the only sensible option. You don’t want them on the guiding coalition, but you also can’t afford to have them outside the meeting room causing problems. Organizations are often reluctant to confront this issue, usually because these people have either special skills or political support. But the alternative is usually worse—having them undermine a new strategy or a cultural renewal effort.

Afraid to confront the problem, we convince ourselves that Jerry isn’t so bad or that we can maneuver around him. So we move on, only to curse ourselves later for not dealing with the issue.

In this kind of situation, remember the following: Personnel problems that can be ignored during easy times can cause serious trouble in a tougher, faster-moving, globalizing economy.

Building an Effective Team Based on Trust and a Common Goal

Teamwork on a guiding change coalition can be created in many different ways. But regardless of the process used, one component is necessary: trust. When trust is present, you will usually be able to create teamwork. When it is missing, you won’t.

Trust is absent in many organizations. People who have spent their careers in a single department or division are often taught loyalty to their immediate group and distrust of the motives of others, even if they are in the same firm. Lack of communication and many other factors heighten misplaced rivalry. So the engineers view the salespeople with great suspicion, the German subsidiary looks at the American parent with disdain, and so on. When employees promoted up from these groups are asked to work together on a guiding coalition during a change effort, teamwork rarely comes easily because of the residual lack of trust. The resulting parochial game playing can prevent a needed transformation from taking place.

This single insight about trust can be most helpful in judging whether a particular set of activities will produce the kind of team that is needed. If the activities create the mutual understanding, respect, and caring associated with trust, then you’re on the right road. If they don’t, you’re not.

Forty years ago, firms that tried to build teams used mostly informal social activity. All the executives met one another’s families. Over golf, Christmas parties, and dinners, they developed relationships based on mutual understanding and trust.

Family-oriented social activity is still used to build teams, but it has a number of serious drawbacks today. First, it is a slow process. Occasional activity that is not aimed primarily at team building can take a decade or more. Second, it works best in families with only one working spouse. In the world of dual careers, few of us have enough time for frequent social obligations in two different organizations. Third, this kind of group development process tends to exert strong pressures to conform. Political ideas, lifestyles, and hobbies are all pushed toward the mean. Someone who is different has to conform or leave. Groupthink, in the negative sense of the term, can be a consequence.

Team building today usually has to move faster, allow for more diversity, and do without at-home spouses. To accommodate this reality, by far the most common vehicle used now is some form of carefully planned off-site set of meetings. A group of eight or twelve or twenty-four go somewhere for two to five days with the explicit objective of becoming more of a team. They talk, analyze, climb mountains, and play games, all for the purpose of increasing mutual understanding and trust.

The first attempts at this sort of activity, about thirty years ago, were so much like a kind of quick-and-dirty group therapy that they often did not work. More recently, the emphasis has shifted to both more intellectual tasks aimed at the head and bonding activities aimed at the heart. People look long and hard at some data about the industry and then go sailing together.

A typical off-site retreat involves ten to fifty people for three to six days. Internal staff or external consultants help plan the meeting. Much of the time is spent encouraging honest discussions about how individuals think and feel with regard to the organization, its problems and opportunities. Communication channels between people are opened or strengthened. Mutual understanding is enlarged. Intellectual and social activities are designed to encourage the growth of trust.

Such team-building outings much too often still fail to achieve results. Expectations are sometimes set too high for a single three-day event, or the meeting is not planned with enough care or expertise. But the trend is clear. We are getting better at this sort of activity.

For example: Division president Sam Johnson is trying to pull together a group of ten people into an effective change coalition for his consumer electronics business. They include his seven direct reports, the head of the one department in the division that will probably be at the center of the change effort, the executive VP at headquarters, and himself. With great difficulty, he schedules a week-long meeting for all ten of them. They start with a two-day Outward Bound type of activity, in which the group lives together outdoors for forty-eight hours and undertakes strenuous physical tasks like sailing and mountain climbing. During these two days, they get to know one another better and are reminded why teamwork is important. On days three to five, they check into a hotel, are given a great deal of data about the division’s competitors and customers, and are asked to produce a series of discussion papers on a tight time schedule. They work from 7:30 a.m. to 7:00 p.m., mostly in ever-shifting, but not randomly chosen, subgroups. From 7:00 to 9:30 each evening they have dinner and talk about their careers, their aspirations, and other more personal topics. In the process, they get to know one another even better and begin to develop shared perspectives on their industry. The increased understanding, the relationships built on actual task achievement, and the common perspectives all foster trust.

Recognizing that this successful week-long activity is just the beginning of a process, Sam hosts another three-day event for the group a few months later. Two years after that, with turnover and promotions changing the makeup of his group, he puts together yet another carefully planned retreat. Just as important, in between these very visible activities, he takes dozens of actions designed to help build the trust necessary for teamwork. Rumors that might erode goodwill are confronted with lightning speed and accurate information. People who know each other least well are put together on other task forces. All ten are included as often as is practical in social activities.

Q: Was this easy to do?

A: Hardly.

Two of the ten in this case were very independent individuals who couldn’t fathom why they should all go climb mountains together. One was so busy that scheduling group activities seemed at times an impossibility. One had a borderline big ego problem. Because of past events, two didn’t get along well. Yet Sam managed to overcome all of this and develop an effective guiding coalition.

I think he succeeded because he wanted very much for the division to do well, because he was convinced that major change was necessary to make the business a winner, and because he believed that that change couldn’t happen without an effective guiding coalition. So in a sense, Sam felt he had no choice. He had to create the trust and teamwork. And he did.

When people fail to develop the coalition needed to guide change, the most common reason is that down deep they really don’t think a transformation is necessary or they don’t think a strong team is needed to direct the change. Skill at team building is rarely the central problem. When executives truly believe they must create a team-oriented guiding coalition, they always seem to find competent advisors who have the skills. Without that belief, even if they have the ability or good counsel, they don’t take needed actions.

Beyond trust, the element crucial to teamwork seems to be a common goal. Only when all the members of a guiding coalition deeply want to achieve the same objective does real teamwork become feasible.

The typical goal that binds individuals together on guiding change coalitions is a commitment to excellence, a real desire to make their organizations perform to the very highest levels possible. Reengineering, acquisitions, and cultural change efforts often fail because that desire is missing. Instead, one finds people committed to their own departments, divisions, friends, or careers.

Trust helps enormously in creating a shared objective. One of the main reasons people are not committed to overall excellence is that they don’t really trust other departments, divisions, or even fellow executives. They fear, sometimes quite rationally, that if they obsessively focus their actions on improving customer satisfaction or reducing expenses, other departments won’t do their fair share and the personal costs will skyrocket. When trust is raised, creating a common goal becomes much easier. Leadership also helps. Leaders know how to encourage people to transcend short-term parochial interests.

TABLE 4–1

Building a coalition that can make change happen

| Find the right people |

| • With strong position power, broad expertise, and high credibility |

| • With leadership and management skills, especially the former |

| Create trust |

| • Through carefully planned off-site events |

| • With lots of talk and joint activities |

| Develop a common goal |

| • Sensible to the head |

| • Appealing to the heart |

Making Change Happen

The combination of trust and a common goal shared by people with the right characteristics can make for a powerful team (see table 4–1). The resulting guiding coalition will have the capacity to make needed change happen despite all the forces of inertia. It will have the potential, at least, to do the hard work involved in creating the necessary vision, communicating the vision widely, empowering a broad base of people to take action, ensuring credibility, building short-term wins, leading and managing dozens of different change projects, and anchoring the new approaches in the organization’s culture.

Again, in a slower-moving, more oligopolistic, less globalized economic environment, all of this effort isn’t usually necessary. But the trends are clear. Today, and more so in the immediate future, we will be seeing many additional attempts to transform organizations. Yet without a powerful guiding coalition, change stalls and carnage grows.