Anchoring New Approaches in the Culture

After years of work, the results were impressive. A once inwardly focused and sluggish aerospace organization was now producing innovative new products at a rapid pace. Not all the offerings were winning in the marketplace, but enough were succeeding that over a five-year period divisional revenues had gone up 62 percent, while net income rose 76 percent; comparable figures for the previous five years were 21 percent and 15 percent, respectively. The division general manager retired, proud that he had helped make an important contribution to the business. He could have stayed a few more years but chose not to: The changes had been made, the results were impressive, the work was done.

At the time of the GM’s departure, I don’t think anyone fully realized that the new style of operating had never been firmly grounded in the division’s culture. If people did, they judged it to be a minor problem. After all, they would say, look at all the change. And look at the results.

Within two years of his retirement, both the new product introduction rate and the success of those products in the marketplace dropped precipitously. Nothing happened suddenly; the regression was all very incremental. At first, no one seemed to notice. After a year, the only top executive who expressed much alarm was a recent arrival from outside the company. Other top executives mostly ignored him.

Here is my postmortem. Some central precepts in the division’s culture were incompatible with all the changes that had been made. Yet that inconsistency was never confronted. As long as the division GM and the transformation program worked day and night to reinforce the new practices, the total weight of these efforts overwhelmed the cultural influence. But when the division GM left and the transformation program ended, the culture reasserted itself.

The primary shared value in that organization, a value firmly established in the business’s early years, was “developing our technology will solve all problems.” Like so much of corporate culture, this idea was never formally stated or written down. When confronted with the belief, most people would readily admit it wasn’t entirely true. But give a group of managers three or four beers and then listen to what they had to say, and you heard a lot that sounded like “developing our technology will solve all problems.”

Because this core value wasn’t diametrically in conflict with the change effort, the two coexisted, although uncomfortably. New practices forced attention first and foremost on customers. The core value would direct it to technology. The new practices were aimed at helping the firm move faster than competitors. The core value said to move at a pace dictated by rational internal technological development.

Someone sensitive to culture would have seen this tension in the company. But because the conflict was so subtle, most people wouldn’t have noticed anything. The communication of the vision, the reinforcement by management, the altered performance appraisal, and other influences strongly supported the new practices. You would have had to listen very closely to hear the underlying culture trying to assert itself: “Yes, but, blah-blah blah-blah, technology, blah-blah blah-blah.”

Because no one confronted this problem, little if any effort was made to help the new practices grow deep roots, ones that sank down into the core culture or were strong enough to replace it. Shallow roots require constant watering. As long as the GM and other change agents were there daily with the garden hose, all was well. Without that attention, the practices dried up, withered, and died. Other greenery that had been cut back, but that had deeper roots, took over.

Within six months of the division GM’s retirement, managers began to more frequently raise questions about business priorities and management practices. Evidence of technological inferiority was nonexistent, yet people said: “I’m afraid that we have been neglecting our technology. If we do that too long, we’ll really be in trouble.” Meetings among engineers, marketing personnel, sales personnel, and customers became controversial. “The engineers are spending so much time in committees outside their work groups, they’re losing their edge.” A competitor that ranked seventh in a group of ten on most performance measures suddenly became a standard for comparison. “I recently heard that they spend nearly 20 percent more than we do per employee on R&D. We’ve got to do something about this.”

Within twelve months of the GM’s retirement, dozens of little adjustments had been made in how the organization conducted business. Few of those changes were explicitly discussed and affirmed by top management. But the senior executives, with the notable exception of the recent hire, gave tacit approval. Within twenty-four months, some practices regressed to where they had been four years before. Shortly thereafter, the first major performance problems began to emerge.

Why Culture Is Powerful

Q: How could an intelligent group of top executives allow something like that to happen?

A: Because their electrical engineering educations, their MBA programs, and their corporate mentors didn’t teach them much about organizational culture, especially its powerful influence on behavior. Living in an overmanaged and underled company for most of their careers just reinforced this blind spot, because culture (and vision) tends to be more the province of leadership, just as structure (and systems) is more of a management tool.

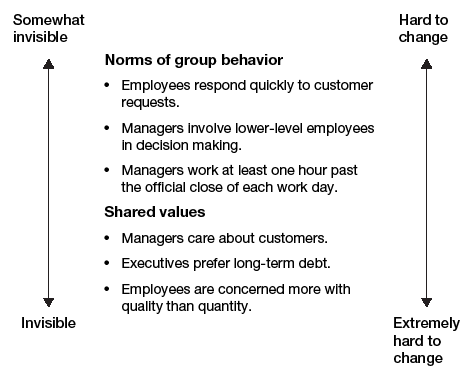

Culture refers to norms of behavior and shared values among a group of people. Norms of behavior are common or pervasive ways of acting that are found in a group and that persist because group members tend to behave in ways that teach these practices to new members, rewarding those who fit in and sanctioning those who do not. Shared values are important concerns and goals shared by most of the people in a group that tend to shape group behavior and that often persist over time even when group membership changes.

In a big company, one typically finds that some of these social forces—the so-called corporate culture—affect everyone and that others are specific to subunits (for example, the marketing culture, the Detroit office’s culture). Regardless of level or location, culture is important because it can powerfully influence human behavior, because it can be difficult to change, and because its near invisibility makes it hard to address directly. Generally, shared values, which are less apparent but more deeply ingrained in the culture, are more difficult to change than norms of behavior. (See figure 10–1.)

When the new practices made in a transformation effort are not compatible with the relevant cultures, they will always be subject to regression. Changes in a work group, a division, or an entire company can come undone, even after years of effort, because the new approaches haven’t been anchored firmly in group norms and values.

To understand why culture can be so important, consider this scenario. You graduate from college, apply for jobs, and get three offers. One of the three companies is so enthusiastic about you, and you feel so comfortable with its employees, that you decide to go work there. As a naive twenty-one-year-old, you assume that you have been selected because of your track record, skills, sterling personality, and promise. You also assume you accepted their offer because the company, in an objective sense, was an excellent corporation. You are mostly oblivious to another major screening criteria: culture.

FIGURE 10-1

Components of corporate culture: Some examples

Source: From Corporate Culture and Performance by John P. Kotter and James L. Heskett. Copyright © 1992 by Kotter Associates, Inc. and James L. Heskett. Adapted with permission of The Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster.

Few if any of the people recruiting you explicitly said: “One of the big reasons we’re hiring you is because we think you will fit in, that you share our implicit values and beliefs, and that you will adjust easily to our norms.” They probably didn’t say this because they are unaware of how strongly they apply cultural criteria in hiring. In accepting their offer, you may also have been oblivious to the weight you were putting on value fit. The net result is that you and probably all your recently hired peers are easy candidates for what is called “socialization”—the inculcation of the company’s norms and values.

During your first year on the job, you’re eager to do well and so are particularly alert to clues about how people are accepted and promoted. As long as those practices don’t seem foolish or unethical, you try to adopt them. Often, the biggest lessons don’t come in a training session or a manual for new employees. The day your boss goes up in smoke over something you do—that is influential. The day you say something in a meeting and a stony silence comes over the group—that is influential. The day an older secretary pulls you aside and reads you the riot act—that is influential. The net result is that you learn and assimilate the culture.

For the next twenty years, you are promoted once every thirty to fifty months. During this time, the culture becomes more and more an instinctive part of you. Indeed, one of the reasons you’ve gotten promoted is because you fit in and get along with the people who decide on promotion. After a while, although you may not be aware of it, you are teaching the new hires the culture. Indeed, at age fifty, as a senior-level manager, you may be almost oblivious to the culture. You have lived in it for so long, and found it so compatible from the beginning, that you relate to the culture as a fish does to water. Because it is everywhere yet invisible, you just don’t think about it, despite the big influence it has on you. Fish get air and food from the water. You get a certain pleasing predictability, lots of positive reinforcement, and a strong emotional attachment to your organization through its culture.

To a large degree, most of the people of your generation in the firm have had similar experiences. Most of these men and women were selected for cultural compatibility. Most had hundreds or thousands of hours of experience in which the norms and values were taught and reinforced. Most now teach the younger employees.

Culture is powerful for three primary reasons:

1. Because individuals are selected and indoctrinated so well.

2. Because the culture exerts itself through the actions of hundreds or thousands of people.

3. Because all of this happens without much conscious intent and thus is difficult to challenge or even discuss.

Consultants, industrial salespeople, and others who regularly see firms up close without being employees know well how much culture operates outside of people’s awareness, even rather visibly unusual aspects of a culture. I can still remember going into a major publishing company about twenty years ago and finding that eight of the top eleven male officers were under 5'8" tall. (The firm’s founder was 5'6".) When I commented on that fact in an off-hand remark that certainly wasn’t meant to be disapproving, the others in the room looked at me as if I were a space alien. At another big company where the first major product had been an explosive and where safety had been an obsession for more than a century, I found that virtually all executives walked up or down stairwells clutching the handrail as if they were all ninety-nine years old.

Because corporate culture exerts this kind of influence, the new practices created in a reengineering or a restructuring or an acquisition must somehow be anchored in it; if not, they can be very fragile and subject to regression.

When New Practices Are Grafted onto the Old Culture

In many transformation efforts, the core of the old culture is not incompatible with the new vision, although some specific norms will be. In that case, the challenge is to graft the new practices onto the old roots while killing off the inconsistent pieces.

For one leading manufacturer of industrial equipment, a “customer-first” attitude had always been at the center of its culture. During the early years, the practices surrounding this attitude were created by the founder and mimicked by everyone else. In the middle part of the twentieth century, with the founder long dead and the firm having a hundred-year history in helping customers, senior management decided to turn this knowledge into explicit procedures that could be taught more easily to an ever-increasing employee base. By 1980, these procedures filled six notebooks, each nearly three inches thick. At that point, “doing it by the book” was a deeply ingrained habit and cultural norm.

In 1983, a new CEO put the company through a major transformation process that was successful. By 1988, the old procedure manuals were no longer used, replaced by far fewer rules and a set of customer-first practices that made more sense in the 1980s. But the CEO realized that the old manuals, while not on people’s desks, were still very much in the corporate culture. So here is what he did.

When he took the stage for his keynote address at the annual management meeting, he had three of his officers stack the old manuals on a table next to the lectern. In his speech he said something like this:

These books served us well for many years. They codified wisdom and experience developed over decades and made that available to all of us. I’m sure that many thousands of our customers benefited enormously because of these procedures.

In the past few decades, our industry has changed in some important ways. Where there once were only two major competitors, we now have six. Where a new generation of products used to be delivered once every two decades, the time has now been cut to nearly five years. Where once customers were delighted if they could receive help from us in forty-eight hours, they now expect service within the course of an eight-hour shift.

In this new context, our wonderful old books began to show their age—they weren’t serving customers as well. They didn’t help us adapt well to changing conditions. They slowed us down. The first evidence we saw of this was in the late 1970s. Although we continued to try to do the right thing, those buying our products didn’t perceive it that way, and it began to show up in our financials.

In 1983, we decided that we had to do something about this—not only because the economic results were looking poor but even more so because we were no longer doing what we wanted to do and had done so well for so long: serve our customers’ needs in a truly outstanding way. We reexamined their requirements and in the last three years have changed dozens of practices to meet those needs. And in the process, we set these guys [pointing to the books] aside.

I think at times all of us worried about whether we were doing the right thing. Well, the evidence is pretty clear now.

He went on at length at this point to review customer satisfaction surveys that showed both improved ratings and clear linkages between those ratings and the new practices.

So I think we are living up to our heritage, despite a difficult competitive situation. I’m taking time to tell you all this today for a number of reasons. I know that there are a few of you in this room, each new to the company in the last couple of years, who think the books over here are a joke, bureaucratic mindlessness in the extreme. Well, I want you to know that they served this company well for many years. I also know that there are people in this room who hate to see the books go. You might not admit it—the logical case for what we’ve done is far too compelling—but at some gut level, you feel that way. I want you to join with me today in saying good-bye. The books are like an old friend who’s died after living a good life. We need to acknowledge his contribution to our lives and move on.

The speech, in its totality, took about thirty minutes. The tone was that of a eulogy. Here we see a man trying respectfully to bury an old set of practices while making sure that their replacements are firmly connected to the group’s core values. The analytical side of our brains has trouble seeing the need for this. If we were only analytical, such a speech wouldn’t be necessary. But human beings are also emotional creatures, and we ignore that reality at our peril.

From all I’ve seen, that speech and associated follow-up measures have been very successful. An almost kneejerk reaction to “do it by the book,” especially among older employees, has been replaced with support for a more sensible set of practices. That’s not a small accomplishment.

In the next few decades, I think we’ll have to be doing a lot more of this sort of limited cultural modification. The increased globalization of enterprises will present one variation on this problem a million times over. The new Korean (or Russian) subsidiary doesn’t have the same customer orientation (or attention to costs) as called for in the corporate vision. The problem is not that the new foreign entity is anticustomer (or anticost), and the solution is not to try to re-create New York in Seoul. The challenge will be to graft some key values onto already well-formed cultures.

Today, I don’t think there are many companies that are very good at this kind of activity. We either ignore norms and values or become cultural imperialists, trying to shove our practices in detail down people’s throats. In a globalizing economy, most of us will be forced to confront this issue in the not so distant future.

When New Practices Replace the Old Culture

Anchoring a new set of practices in a culture is difficult enough when those approaches are consistent with the core of the culture. When they aren’t, the challenge can be much greater.

Consider a firm founded in 1928. The key experience that shaped its culture was the Great Depression, and as a result, conservative—if not risk-averse—norms and values permeated the company. When the firm stumbled badly in the late 1980s and a new top management team engineered major changes, the tensions between its take-a-risk practices and the old culture were gigantic. Even after top management communicated 100 percent support for the new methods and the evidence began to accumulate that they were working, the old culture refused to die, especially in one part of the company.

What did these managers do? Briefly:

1. They talked a great deal about the evidence showing how performance improvements were linked to their new practices.

2. They talked a great deal about where the old culture had come from, how it had served the firm well, but why it was no longer helpful.

3. They offered those over fifty-five an attractive early retirement program and then worked hard to convince anyone who embraced the new culture not to leave.

4. They made doubly sure that new hires were not being informally screened according to the old norms and values.

5. They tried hard not to promote anyone who didn’t viscerally appreciate the new practices.

6. They made sure that the three candidates being considered to replace the CEO had none of the Depression-era culture in their hearts.

Even with all of these efforts, killing off the old culture and creating the new one was difficult to accomplish. Shared values and group norms are persistent, especially the former (see figure 10–1). When shared values are supported by the hiring of similar personalities into an organization, changing the culture may require changing people. Even when there is no personality incompatibility with a new vision, if shared values are the product of many years of experience in a firm, years of a different kind of experience are often needed to create any change.

And that is why cultural change comes at the end of a transformation, not the beginning.

Cultural Change Comes Last, Not First

One of the theories about change that has circulated widely over the past fifteen years might be summarized as follows: The biggest impediment to creating change in a group is culture. Therefore, the first step in a major transformation is to alter the norms and values. After the culture has been shifted, the rest of the change effort becomes more feasible and easier to put into effect.

I once believed in this model. But everything I’ve seen over the past decade tells me it’s wrong.

Culture is not something that you manipulate easily. Attempts to grab it and twist it into a new shape never work because you can’t grab it. Culture changes only after you have successfully altered people’s actions, after the new behavior produces some group benefit for a period of time, and after people see the connection between the new actions and the performance improvement. Thus, most cultural change happens in stage 8, not stage 1.

This does not mean that a sensitivity to cultural issues isn’t essential in the first phases of a transformation. The better you understand the existing culture, the more easily you can figure out how to push the urgency level up, how to create the guiding coalition, how to shape the vision, and so forth. Nor does this mean that changing behavior isn’t a key part of the early stages of a transformation. In step 2, for example, you are typically trying to alter habits and create more teamwork among a guiding coalition. Nor does this mean that some attitudinal changes are not a part of step 1, where complacent worldviews are attacked. But the actual changing of powerful norms and values occurs mostly in the very last stage of the process, or at least the very last stage in each cycle of the process. So if one of the change cycles in a larger transformation effort is associated with a reengineering project in department X, that project will end with an effort to anchor the work in the department’s culture.

A good rule of thumb: Whenever you hear of a major restructuring, reengineering, or strategic redirection in which step 1 is “changing the culture,” you should be concerned that it might be going down the wrong path.

Both attitude and behavior change typically begin early in a transformation process. These alterations then create changes in practices that help a firm produce better products or services at lower costs. But only at the end of the change cycle does most of this become anchored in the culture.

I’ve seen a dozen cases over the past decade in which the senior VPs of human resources were assigned to “change the culture” in firms with no overall transformation process or in firms with a project that was run independently or ahead of bigger change efforts. Typically, these HR managers struggled along for a few years trying hard to do something useful. They would produce statements of desired values or group norms. They would hold meetings to communicate this information. Sometimes they would launch training programs to “teach” the values. But as staff executives, they were in a weak position to introduce a major change that would affect the entire organization. And the basic conception of the proposal—to get in there and hammer that culture into shape—made success virtually impossible from the outset.

TABLE 10-1

Anchoring change in a culture

| • | Comes last, not first: Most alterations in norms and shared values come at the end of the transformation process. |

| • | Depends on results: New approaches usually sink into a culture only after it’s very clear that they work and are superior to old methods. |

| • | Requires a lot of talk: Without verbal instruction and support, people are often reluctant to admit the validity of new practices. |

| • | May involve turnover: Sometimes the only way to change a culture is to change key people. |

| • | Makes decisions on succession crucial: If promotion processes are not changed to be compatible with the new practices, the old culture will reassert itself. |

Some observers are dismissive of these cases and the people associated with them. But I’ve found these executives are usually smart, dedicated, and hard-working individuals. Their failures tell us less about them than about the extraordinary difficulty of changing corporate culture. (See table 10–1, which sums up the key features of anchoring cultural change.)

It is because such change is so difficult to bring about that the transformation process has eight stages instead of two or three, that it often takes so much time, and that it requires so much leadership from so many people.