12

Stock Photo Agencies and Decor Photography

OUTLETS FOR TRACK A

Stock photo agencies can offer opportunities or headaches. There was a time when it was fairly easy to place photographs with stock agencies. Photographers placed their “grab shots” with agencies, and the agencies happily accepted most of what they could get. Gradually the agencies became more and more selective as volume increased and the demands for high-quality stock images became more frequent.

That trend continues today, making it harder to get into a top agency. The agencies are becoming even more selective as to the quantity of images, kinds of images and number of new photographers they accept.

Stock agencies are going one of two ways: Either they become huge and broad (generic), or they become small and highly specialized (niche). Unless you’re a recognized name in the industry, the smaller, more specialized agency is likely to be a better option for you rather than the huge agency where it’s easy to become just a number amongst dozens of others.

It used to be that the vast majority of agencies were located in, or were very close to, New York City. Not so anymore. While it’s still true that a great many stock agencies are in Manhattan, more and more smaller agencies—I call them “micro agencies”—are popping up all over the country. These micro agencies are most often very specialized and deal with only a handful of subject areas.

For the photo buyers, this great plethora of agencies is a good thing. If a photo buyer is looking for something generic, she looks to a big, generic agency. If she’s looking for something highly specific, thanks to the Internet, she turns to a micro agency or to an individual photographer.

Photo buyers use agencies for all kinds of photo needs. The reason many photo buyers would rather deal with an agency than an independent photographer is that they think they will be sure to receive professional treatment. If you show these photo buyers that you can present them images of equal quality as the agency does, with equal reliability and professionalism, chances are the photo buyers will turn directly to you instead. Photo buyers who use stock agencies range from book and magazine publishers to ad agencies and public relations firms. These photo buyers have one thing in common: They can pay the high fee that stock agencies demand.

Everything New Under the Sun

If your goal is to supply generic pictures to a stock agency, take note of the kinds of pictures in current newsstand magazine ads. Two other indicators of what buyers are currently after are the websites of major stock agencies such as Corbis and Getty Images. Also check out the major catalogs such as the Black Book, American Showcase, Klikk and Workbook, and the websites of Comstock, Corbis Stock Market, SuperStock and Alamy.

Keep in mind that commercial stock photography is much like the fashion industry. What’s popular today is “old hat” tomorrow. So your research on the style and content of the pictures you see online or in catalogs may be useful to you for only a short while. It’s an ongoing, ever-changing process. While the “standard current images will always have a chance to sell, remember that buyers like to find innovative, creative photo suppliers, too.

Brian Yarvin, www.brianyarvin.com, an experienced commercial stock photographer from Edison, New Jersey, says, “Generic pictures are available as clip art (royalty free, or RF) these days, so few agencies would try licensing generic images as rights-protected. Today’s successful agency stock photographer knows his market and shoots for that market with great creativity. Agencies are going more and more toward targeting the commercial stock photo market.

“Signing on with an agency is like signing any other business agreement. Do your research ahead of time and make sure that you do business with the agency that’s right for you. When you do your research you might find out that you need to sign up with several agencies to get what you want, and there’s certainly nothing wrong with that,” Yarvin says.

What should you submit to an agency? You should edit your work ruthlessly and send only your best work, at least for the initial submission. The good news is that these days, basically any format goes.

“Agencies are much more open to reviewing different formats these days, and I’m not talking just different-size transparencies. Digital, prints, Polaroid transfers, virtually anything is possible,” says Yarvin.

“You should check with your agency prior to submitting anything other than what they state they accept, but you might be surprised to learn how open most agencies are these days to submissions that are a bit out of the ordinary.”

Prepare to Share Your Profit

Stock agencies do demand high fees. They can afford to because they offer the photo buyers something they can’t get anywhere else—a huge selection at their fingertips. It’s this fact, so attractive to photo buyers, that is your disadvantage. If your picture of a windmill or frog or seagull is being considered for purchase among dozens and dozens of others in the same agency—never mind competing agencies—your chance of scoring is minimal.

Even against this reality, however, the chances of that kind of Track A picture selling are greater at an agency than if you tried to market such shots yourself.

Does big money await you when you go with an agency? As Brian Yarvin says, it depends on how well you choose your agencies and how often you supply them with your targeted photos. Agencies will tally their sales for you on a monthly, quarterly or semiannual basis and send you a check. Although this check is for only 40 to 50 percent of the agency’s sales fee (the agency retains the remainder), it’s always welcome. (From $40 to $150 is the current range of your share of an average sale.) Most photographers, whether they are service or editorial stock photographers, count on agency sales only as a supplement to the rest of their photography business.

So how much money can you expect from the agency you have selected to work with? It used to be $1 for every photograph you have in the agency, per year. This is no longer true. There are too many variables these days to give a general figure. However, if one of your images makes it into the agency’s paper catalog, figure around $1,000 per that image per year. If an image makes it onto the website of an agency, figure around $500 per such image per year. These figures are based on what the larger, established agencies are making, and if the agency you have chosen is a modest size or isn’t as well established, you can expect to make less than the above.

Agencies: A Plus with Limitations

As I mentioned, most experienced photographers expect agency sales to only be a supplement to the rest of their photography business. Many newcomers to photomarketing (and some not so new) sometimes think they can relax once their pictures are with an agency. They believe that now they can concentrate on the fun of shooting and printing and check cashing, and let the agency handle the administrative hassles of marketing.

It just doesn’t work that way. Most stock photographers still have to market images themselves as well.

However, making money through the agencies is a bit like gambling. You can increase your chances of making regular sales through agencies if, as at the baccarat table, you study the game.

Agencies offer the pluses of good prices and lots of contacts, but they have limitations that affect the sale of your pictures. One is that monumental competition faced by any one picture. Another is that no agency is going to market your pictures as aggressively as you do yourself. The agency has something to gain from selling, yes, but it spreads its efforts over many photographers.

Another limitation, which you can turn into a plus once you’re aware of it, is that different agencies become known among photo buyers as good suppliers in some categories of pictures but not in others. Like art galleries, agencies tend to be strong in certain types of pictures. Sometimes, however, an agency will accept photos in categories outside its known specialties. If you place your pictures in the wrong agency, your images won’t move (sell) for you.

THE SPECIALIZATION FACTOR

When a photo buyer at a magazine or book publishing house needs a picture, he assigns the job of obtaining that picture to a photo researcher, a person (often a freelancer) who is adept at finding pictures quickly for a fee. The researcher checks the Internet or makes a beeline for a local agency that she knows is strong in the category on the needs sheet.

If a book publisher, for example, is preparing a coffee-table book on songbirds, the researcher will know which agency to visit, and it might not be an agency you or I have ever heard of. It might not even be in New York.

Photo researchers know that agencies, like magazine and book publishers, have moved toward specialization. By going to an agency that she knows is strong in songbirds, the researcher knows she’ll have not a handful of pictures to choose from, but several hundred. Often the picture requirements will demand more than simply “a blackbird.” It will specify the background, the type (Brewer’s or red-winged), the time of the year (courtship, nesting, plumage changes), the action involved (in flight, perching or a certain close- up position)—and the wide selection will be particularly necessary.

Researchers feel that they’re doing their clients justice in choosing agencies they know will have a wide selection. If your pictures of birds or alligators are in a different, more generalized agency, they may never be seen.

The first order of business in regard to agencies, then, is to research the field and pick the right ones for your mix of categories. You can have your pictures in several agencies at once, as Brian Yarvin mentions. Choose them on the basis of geographical distribution (an agency in Denver, one in Chicago and one in New York) and on the basis of picture-category specialization (scenics at one, African wildlife at another, horses at the third).

HOW TO FIND THE RIGHT AGENCY

If your photography is good, just about any agency will accept it, whether or not they’re looked to by photo buyers as strong in your particular categories. That’s where the danger lies. How, then, can you find the right agency—or agencies—for you?

It takes time, but here’s one approach. Part of your task on the second weekend of your Five-Weekend Action Plan (see chapter four) is to separate your pictures into Track A categories on the one hand and your PS/A on the other. Take both your Track A and PS/A lists, and narrow them down to the areas where you have the largest number of pictures.

Let’s invent an example. Say that in Track A (the “standard excellents”) you isolate three areas in which you are very strong: squirrels, covered bridges and underwater pictures. In your Track B PS/A, you isolate five strong areas: skiing, gardening, camping, aviation and agriculture. Taking your Track A pictures first, do some research and find which agencies in the country are strongest in each of your three categories, rather than placing all three Track A categories with one general agency.

You might find that your covered-bridge pictures land in a prestigious general agency in New York or Seattle that happens to have a strong covered-bridge library. You will supply that agency with a continuing fresh stock of covered bridges, and they will move your pictures aggressively. Your underwater pictures might land in a small agency in Colorado that is noted for its underwater collection. Again, your pictures should move, since photo researchers will know to look to this agency for underwater shots.

Your covered bridge pictures fall into Track A; you would probably have difficulty marketing them on your own. But how about your Track B pictures, like your camping or agriculture shots? Should you place them in an agency, too? Or will you be competing against yourself since you will be aggressively marketing your Track B pictures to your own Market List?

Your answer will depend on your Track B pictures themselves, their particular categories and your Market List. If your own marketing efforts are fruitful, you will do best to continue to market your Track B categories yourself. If certain of your Track B pictures move slowly for you, you might find it advantageous to put them in an agency. (If you do, place your slower-moving Track B categories in different agencies with the same forethought you gave to your Track A categories.)

RESEARCHING THE AGENCIES

Determining the strengths of individual agencies will take some research on your part. The magazines, books and websites that are already using pictures similar to yours will be your best aid. As an example, let’s take your Track A squirrel pictures.

Being a squirrel photographer, you naturally gravitate to pictures of squirrels. If you see one in a newspaper, encyclopedia, website or textbook, it attracts your eye. Make a note of the credit line (if there is one) on each squirrel photograph. It will be credited with a photographer’s or an agency’s name in about a third of the cases. (Picture credits are sometimes grouped together in the back or front of a magazine or book.) If, after six months of this kind of research, the same stock photo agency name keeps popping up, your detective work is paying off. (Sometimes, depending on your Track A category, two or three agency names will appear. This is a plus. It means you can be choosy about whom you eventually contact, basing your decision on how long each agency has been in business, its location, whether it has an impressive website and so on.) Locate the photo agency’s address in a directory such as Photographer’s Market or through an Internet search engine. You can research the needs of a variety of stock photo agencies by consulting the latest edition of Photographer’s Market. You’ll also learn what formats the agency accepts as well as payment terms.

You also can check agencies out by contacting the Picture Agency Council of America (PACA). It has 150 members. Send $15 plus an SASE for a list showing members’ specialties. (This list will help you locate agencies and the categories of pictures they carry, but you’ll learn more about where photo buyers go, and for what, through your own research.) Contact PACA at 3165 S. Alma School Road, #29-261, Chandler, AZ 85248, (714) 815-8427, www.pacaoffice.org.

Signing up with an agency is just like signing any business agreement/contract. You have to do your research and make certain that the agency you’re signing up with is solid, honest and will meet your expectations. The best, and possibly easiest, way to check out an agency is to ask them for some references of other photographers who have been with the agency for at least a couple of years. If the agency refuses to give you any references, forget them and move on.

Ask a lot of questions before signing up with an agency, but make sure you ask them in a letter or an e-mail. This gives the agency a chance to respond when they can, rather than trying to force a rapid response over the phone.

How to Contact a Stock Photo Agency

Agencies, like photo buyers, expect a high reliability factor from you. If you’re certain that you have discovered an agency that is strong in one or more of your categories, contact the agency with a forceful letter.

Your first paragraph should make the agency director aware that you have been doing some professional research and that you aren’t a fly-by-night who just happened to stumble onto the agency’s address.

Let the agency know the size and format of the collection you are offering. If you place special emphasis on a certain category or if you live in or photograph in a unique environment, state this also.

Impress upon the agency that your group of pictures is not static, that you continually add fresh images. (Some photographers hope to dump an outdated collection on an agency.)

Tell the director that you’re considering placing this particular collection in a stock house. Give the impression that you’re shopping, not that you’re expecting or wishing to place your pictures with him.

If your research is accurate and your letter professional in tone and appearance, the photo agency will welcome your contribution to its library. More important, your pictures will be at an agency known for a specialty that happens to be your specialty.

In some cases you can make a personal visit to an agency instead of writing a letter. A few agencies in the large cities designate one day of the week as a day when photographers can come in to display their photos for consideration.

Categorize your pictures before you step into an agency. The director will want to see the best you have on the subjects that interest him. Be ruthless in your editing to make sure you really put your best foot forward. Directors at agencies see a lot of photos, and the easier you can make their job, the better.

Once an agency says, “Okay, we’ll carry your pictures,” how many should you leave for their files? If it’s a highly specialized agency a smaller number of high-resolution digital images or slides (two vinyl sheets if the agency is still accepting slides) is acceptable. A general agency would expect ten to fifteen of your vinyl pages or several hundred high-resolution digital images. The digital format most often requested is jpg. You would be expected to update this selection with twenty to forty new photos at a time, every six months to a year.

The agency will specify how your pictures should be identified and keyworded. For example, on slides most agencies want the agency’s name at the top and the caption information at the bottom. Your identification code, name, address and telephone number should appear on the sides. They’ll want to know which pictures have a model release (MR) or a model release possible (MRP).

Agencies will send you their standard contract form in which they’ll stipulate, among other things, that they will take 50 (sometimes 40, sometimes 60) percent of the revenue from picture sales. Expect them to require you to keep your pictures on file with them for a minimum of five years. (If after a period of time you want your pictures returned, an agency may take up to three years to get them back to you.)

The Timely Stock Agencies

A few editorial picture agencies deal in current photojournalism and sell for the service photographer who supplies fresh, news-oriented pictures. These agencies, again, are based in New York, and they send individuals or teams to trouble spots or disaster areas, much as a local or regional TV camera crew covers news of immediate interest. Most of these agencies, with channels or sometimes headquarters in Europe, sell single photographs and provide feature assignments around the globe for their top-ranking photographers. If you happen to photograph a subject, situation or celebrity that you think has timely national or international impact, contact one of the following agencies:

Black Star; www.blackstar.com.

Contact Press Images; www.contactpressimages.com.

Sygma/Corbis; www.corbisimages.com.

Getty Images; www.gettyimages.com.

Payment for your picture or picture story is based on several factors: (1) exclusivity (has the rest of the world seen it yet?), (2) impact (would a viewer find your picture(s) of interest?), (3) your name (if your name is Rick Smolan, add 200 percent to the bill), (4) timeliness (is it of immediate interest?). The following agencies will accept the kind of pictures and picture stories mentioned above, but they also will accept non-deadline human-interest pictures and stories:

The Associated Press (AP); www.ap.org

United Press International (UPI); www.upi.com

Stock Agency Catalogs

Many of the major stock agencies produce print catalogs. In most cases you’ll have to pay, by the photograph, to be included. All things being equal, the venture generally turns out profitable for the photographer. Some agencies also produce a catalog on CD-ROM. As online galleries become more popular, CD-ROM catalogs may lose their effectiveness.

Possible Problems in Dealing with Stock Agencies

In dealing with a stock photo agency, remember: You are the creator, you are in control and you own your picture.

Investigate as thoroughly as possible all agencies you’re thinking of joining before you sign anything.

CONTRACTS

Read any stock agency contract very carefully. Most photo agency contracts ask you to sign with them exclusively. Some stipulate that if you market any picture on your own, 50 percent of those revenues become theirs. Some agencies ask that you shoot stock pictures on a regular basis and send the results to them. If you fail to do so, they assess a maintenance charge to your account.

Treat contracts as agreements to be modified by both parties. Draw a line through any section in the contract that you disapprove of, and initial it. If your pictures aren’t returned to you shortly thereafter, you’ll know that the agency values the opportunity to market your pictures more than having you agree on the point or points you deleted from the contract. (Be prepared for possible negotiation and sharing of concessions with the agency.)

CONFLICTS

Some photo agencies may express wariness of a possible sale conflict—say, two competing greeting card companies buying the same picture—if the agency, plus you, plus one or two other agencies in the country are marketing your pictures. Explain to the agency that you have placed your pictures by category with agencies that are strong in these differing categories, and that you have not placed the same picture (or a duplicate) in competing agencies and don’t intend to.

Could a problem still arise on a major account where significant dollars are involved? In such a case, the art director would thoroughly research the pictures with you for releases, history of the picture, previous uses of it and so on before it is used. Any inadvertent duplication or possible sales conflict would come to the fore at that time.

In any case, if you’ve signed up on a nonexclusive arrangement with a stock agency, you put the burden of follow-up on the history of sales of a particular picture on the stock agency that handles your photos, not on yourself.

DELAYS

You’ll be more likely to run across a problem in the area of delays. By far the highest percentage of complaints that used to come into the PhotoSource International office are about the slowness of stock agencies to move pictures. (“I know they could sell my stuff, but they don’t try. They don’t actively keep my pictures moving for sales. They’re selling other photographers’ work, but not mine!”)

Rohn followed up on every complaint and found that in all cases the grief could have been avoided. The problem usually lies in the eagerness of both parties.

The eagerness of stock photo agencies to supplement their stock of pictures by accepting categories of photos outside their known strength areas can be likened to the well-run garage that keeps its well-paid mechanics busy. They accept any job, any make of vehicle, foreign or domestic. They pride themselves on their versatility. The fact is, no one is that versatile. Someone usually loses—more likely than not, that somebody is the customer. With a little research, the auto owner could have found the right garage for his car and his pocketbook.

By the same token, the eagerness of photographers to have their photos accepted into a prestigious stock photo agency for the sake of the name, rather than on the basis of research showing the agency as being strong in their specific categories, gives rise to the complaint, “They don’t aggressively move my material!”

If your pictures of Alaskan wildlife, for example, were placed in the ABC Agency, a well-known, prestigious agency, a photo researcher seeking wildlife pictures would bypass that agency if it were not known for a strong wildlife selection. Instead, the researcher would head for the smaller Accent Alaska agency, for example, which is strong on wildlife. Do your research and choose your agencies with care.

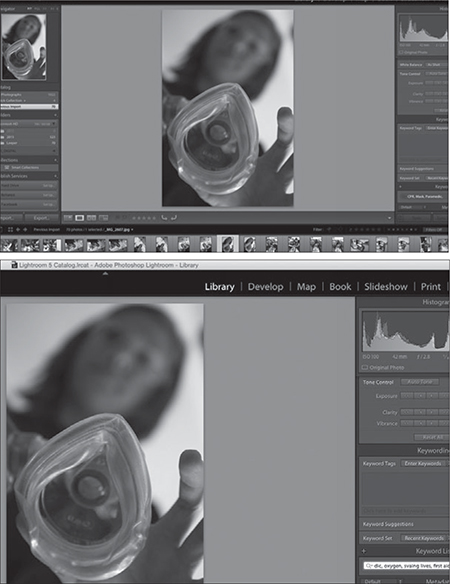

Figure 12-1. This is a screen shot of what the caption screen looks like in Adobe® Photoshop® Lightroom. Lightroom is a versatile piece of software that you can use to develop your RAW photos (see chapter seventeen), catalog your photos, resize and caption your photos and much more.

HONESTY

There are other complaints and problems. I often hear them in this form: “Are they honest? I’m not receiving checks for all the pictures of mine the agency is selling.”

If it’s any consolation, I have heard of only one documented case in which it turned out that a major stock photo agency purposely attempted to carry out this scenario. I know it happens, but I believe it rarely happens on purpose. Stock agencies trade on their own reliability factor, just as you do.

As a free-agent stock photographer, you place yourself at the mercy of the basic honesty of all the contacts you make in the world of business. That’s one of the disadvantages of being a freelancer, and it’s probably a good reason that there aren’t too many of us. Before you place your pictures with a stock photo agency, find out as much as you can about the agency. If it’s a good match, then take a leap of faith.

Do You Need a Personal Rep?

What stock photo agencies do for photographers on a collective basis, representatives do on an individualized basis. A rep earns a living by securing the best price for your single pictures and the best fee for your photographing services. There’s an old saying in the business, “You’ll know if you qualify for a rep because the rep will come to you—just when your photography has finally arrived and you don’t need a rep anymore.”

Can a rep be of benefit to you? Yes, especially by freeing you from the confinements of administering your sales. You’ll have more time to take pictures. However, reps can be expensive. Depending on the services they provide to you, they take from 20 to 50 percent of the fee. Most reps are in New York and Los Angeles, where so many commercial photo buyers are located.

Unless you live in a city with a population of over a million and your name is well established in the industry, you and a rep would not find each other mutually beneficial.

Using a Stock Agency

Photo buyers have the choice of dealing with a massive agency (Corbis for Getty Images, for example) or a small specialty agency. Depending on where you choose to place your pictures, the photo buyer will find your agency. If you choose to set up your own website and develop a highly specialized collection of photos, you may fare better than if you join a massive agency.

Start Your Own Mini-Agency

If a stock agency or a rep is not for you, but you want the photo agency system for marketing your pictures (i.e., you want someone other than yourself to handle the selling), and you want a more aggressive approach to the sale of your photographs than you get with a regular agency, then establish a mini stock photo agency of your own to handle your pictures. You can do this on an individual basis, or get together with one or more other photographers to form a co-op agency. Both forms of mini-agencies (sometimes called “micro agencies”) have advantages. Both can be set up as websites.

THE INDIVIDUAL AGENCY

Find a person (friend, neighbor, spouse or relative) who has spare time, an aptitude for elementary business procedures and a desire to make some money. An interest in photography is helpful but not necessary. More important, the person should have the temperament for record keeping and the ability to work solo.

Your job will be to supply the finished pictures. Your cohort’s job will be to search out markets, handle inquiries, send digital previews, send out photos, keep the records and process e-mail and postal mail. From the gross sales each month, subtract the expenses off the top and split the net fifty-fifty. (There won’t be many expenses: postage, phone, mailing envelopes, stationery, invoice forms and miscellaneous office supplies such as rubber bands and paper clips.)

Before you start up your mini-agency, decide on a name and design a letterhead and invoice form. Open a business checking account. Work up a letter of agreement with your colleague that in effect will say the following:

- You will split the proceeds fifty-fifty after business expenses. All pictures, transparencies and the name of the agency will revert to you, the photographer, in case of termination of your business arrangement. Also, the back of your prints will show your personal copyright—not the agency’s.

- Bookkeeping records will be kept by your colleague, who will pay you from the business checkbook. Major purchases will be mutually agreed upon and the cost divided between the two of you. (Should you incorporate at this point? Probably not, but it depends on many variables that only you can answer. See the list of business information books in the bibliography.)

- Your colleague also may collect other photographers’ work to market. Reason? IRS rules state that if other photographers’ work is also represented, then your colleague is not an employee of yours (which requires employment records), but rather an independent contractor, which requires no government paperwork on your part. Your colleague fills out his own tax forms. You fill out Form 1099 for him.

The success of your mini-agency will depend on the efficiency of your retrieval system—designed for the convenience of both the office help and the walk-ins (i.e., photo researchers looking for pictures). Pictures should be categorized and filed with attention to physical ease of retrieval. Chapter thirteen will help you with this.

For business reasons, as a mini-stock agency you may want to explore joining the following organizations. (Membership can add credibility on your business stationery, and both provide newsletters with information from the picture-buying point of view, which can be valuable to your operation.)

Picture Agency Council of America (PACA), 3165 S. Alma School Road, #29-261, Chandler, AZ 85248, (714) 815-8427, www.pacaoffice.org.

American Society of Picture Professionals (ASPP), 409 S. Washington Street, Alexandria, VA 22134, www.aspp.com.

If you’ve chosen a good, aggressive colleague, once your one-person agency is set up and rolling, you’ll find that you’ll be able to concentrate more on picture-taking and less on administration.

THE CO-OP AGENCY

Some photographers prefer to band together and form a cooperative agency, an establishment in which nonphotographer members handle the administration and photographers handle the picture-taking. The nonphotographers share office-sitting chores, and they are compensated on a total-hours-contributed basis.

I have watched the demise of many micro agencies, and the failure always can be traced to a concept problem: They attempted to be a general agency servicing local accounts. This seems logical enough, but a local account figures if it’s going to pay national prices, it ought to get its pictures from a national source—and it does. Using the Internet or convenient express services, such as UPS and FedEx, it bypasses the local agency.

THE MICRO AGENCY ON THE RISE

If recent editions of the popular annual directory Photographer’s Market can be used as a benchmark, midsize to small stock agencies (micro agencies) are on the rise, not the decline.

Our guess would be that despite the introduction of royalty free (RF) and the influence of Corbis and Getty Images, micro stock agency entrepreneurs have seen a niche opening up for them. In other words, Budweiser, Miller and Coors don’t have the entire beer market wrapped up; the micro breweries found their niche, just as small stock agencies are doing.

Although these micro agencies are two- and three-person operations in many cases, and many as yet have not turned a profit, they are a sign that increasing numbers of photo buyers are seeking specialized images that more precisely match the scope and theme of their publishing enterprises.

It may be that part of your photo files might belong in agency X, another part in agency Y and yet another in agency Z. You could market your remaining images (or digital duplicates) yourself.

| Year | Number of Stock Agencies in Photographer’s Market |

| 1996 | 181* |

| 1997 | 202* |

| 1998 | 174* |

| 1999 | 200** |

| 2000 | 230** |

| 2001 | 235*** |

| 2002 | 240*** |

| 2003 | 240 |

| 2005 | 227 |

| 2009 | 141 |

| 2013 | 148 |

| 2015 | 144 |

* Majority were general agencies.

** Transition: larger agencies are decreasing; smaller specialized agencies are increasing.

*** Majority are small to midsized specialized agencies. Only a few general agencies.

Photographer’s Market, F+W Media Inc.

THE MICRO AGENCY

The solution for a small regional agency is to specialize and become a

micro agency. For example, a small agency in Nebraska might specialize in submarines, an agency in Vermont might specialize in things Mexican and an agency in Florida might specialize in pro-football celebrities. In today’s world, where distance has been annihilated by electronic delivery, express mail and computers, there’s little reason for a Montana agency to specialize in the obvious—cowboys. It’s more important for an agency to be a mini-expert in one particular field, such as outdoor recreation, and if possible specialize in one of the subcategories of that field—snowboarding, for example. You’ll then gather the pictures from all over the country, and the world, if need be.

The local clients might continue to ignore your micro agency, but not when they need your specialty. When they do need what you can provide, you’ll find them standing in line with the rest of your national and international accounts.

How many pictures should you have on file to start your micro agency? At least five thousand when you specialize. How do you find qualified stock photographers? A few will come out of the woodwork locally. A good resource is the Web. At your favorite search engine, type in two words, your subject, and the word photo. Depending on the specialization, potential photographers’ names will come up. Other sources are directories (see Table 3-1 on pages 56-57) such as Literary Market Place, ASPP, APA and ASMP membership directories. List your agency in Photographer’s Market, and photographers who specialize in the subject you wish to cover will come to you.

Before you launch your micro agency, think like a marketer. Ask yourself, “Will my agency have customers?”

To find out the answer, use the power of the Web. Here’s how. Let’s say you’re interested in antiquity, and your specialty will be archaeology. Using a search engine, type in “associations.” For example, the Directory of Business and Trade Associations in Canada lists 19,000 Canadian and foreign associations. You’ll find fourteen archaeological societies and organizations listed worldwide.

Next step is to contact them to find the conventions and conferences these associations hold.

You’ll choose a conference to attend, and you’ll set up a display booth for your stock agency’s images. The experience will not only pay for the cost of your exhibit (don’t forget it’s a write-off on your taxes), but it also will provide you with long-term contacts that will result in first-name basis working relationships with many of your clients.

When you decide on a specialization, don’t choose a broad topic, such as health care. Instead, choose nursing, fitness, disabilities, nutrition and so on. You’ll be rewarded with many sales because you have pinpointed your client’s specific needs. They won’t have to look further than your agency to find the photos they require.

Decor Photography: Another Outlet for Your Standards

As a stock photographer, you’ll find that many of your Track A pictures lend themselves to decor photography (or photo decor, decor art, wall decor or fine art, as it’s sometimes called)—photographs that decorate the walls of homes, public places and commercial buildings. In contrast to your work in stock photography, you will be selling prints, not slides.

The two basic ways to sell photography for decoration are (1) single sales (yourself as the salesperson) and (2) multiple sales (an agent as the salesperson). In either case you, or the person you appoint to select your prints for marketing, should have a feel for the art tastes of the everyday consumer. You’re headed for disaster if you choose to market prints that appeal only to your sophisticated friends. You’ll ring up good decor sales if you can match the kind of photos found on calendars, postcards and greeting card racks.

I suggest that, as a beginner, you offer your photo decor on consignment. You can expect to receive a 50 percent commission from your retail outlets for your decor photography.

SINGLE SALES

Art shows, craft shows and photo exhibits of all kinds are typical outlets for single sales of your decor photography. Aggressively contact home designers, architects, remodelers and interior decorators. They are in constant need of fresh decorating ideas. Your pictures can add a local touch. Gift shops, frame shops and boutiques can be regular outlets.

Art fairs provide an opening into the decor-photography market. Offer your pictures at modest fees. (Most visitors come to an art fair expecting to spend no more than a total of $60–70. Let this be your guide.) You’ll find that you can make important contacts at art fairs that will lead to future sales. Pass out your business cards vigorously.

There are two categories of decor photographers at major art fairs: those who net $40 for the weekend, and those who net $4,000. The former group wears work jeans and relaxes at their booths in beach chairs. The latter group consists of equally excellent photographers who have studied the needs of consumers, present their work in a professional-looking booth and are aggressive salespersons.

Miller Outcalt, writing in PhotoLetter, says that exhibitor entrance fees at art fairs range from $25 to $250, with the average being $90. Most fairs are held on weekends, usually from 10:00 A.M. to 5:00 P.M. Setup time is usually at 7:30 A.M.

RESOURCES

Photo galleries offer important exposure and sales opportunities for your decor photography. The Photographic Resource Center at Boston University, 832 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, (617) 975-0600, produces aids for photographers, including The Photographer’s Guide to Getting and Having a Successful Exhibition. Support organizations can be found at Art-Support.com. Several books on the subject of art and decor marketing are available from North Light Books, an imprint of F+W Media Inc., (10151 Carver Road, Blue Ash, Ohio 45242, (513) 531-2690), www.artistsnetwork.com.

The single-print sales system that requires person-to-person contact can be time-consuming, cutting into your profits. However, if you enjoy the excitement and camaraderie of art fairs and public art exhibits, it can be rewarding. Probably the most lucrative market channel for single sales would be architects and interior designers. They are in a position to sell your pictures for you.

WHAT MAKES A MARKETABLE DECOR PHOTOGRAPH?

Answer: One that makes your viewers wish they were there. Choose a view or subject you would enjoy looking at 365 days a year. If you don’t like the view or subject, chances are your customers won’t either. Keep in mind that most buyers of decor photography enjoy pictures of pleasant subjects because they find in such pictures an escape from the hassle and routine of everyday living.

That’s why, for this market, it’s important to take your scenics without people in them. Your viewers would like to imagine themselves strolling through the meadow or along the beach. Figures that are recognizable as humans in your picture are an intrusion on the viewer’s own quietude and privacy. In addition, people included in decor photography can date the pictures with their clothes, hairstyles and so on.

Here are some excellent standards that sell over and over again for decor-photography purposes:

Nature close-ups. Zooming in on the details of the natural world at the correct f-stop always produces a sure seller. These subjects rarely become outdated: dandelion seeds, frost patterns, lichen designs, the eye of a peacock feather, the quills of a porcupine or a crystal-studded geode. Decor-photography buyers tend to buy easily recognizable subjects. An antique windmill would consistently sell better than an antique wind generator (the kind with propeller blades); a still life of a daisy would sell better than a still life of potentilla.

Keep your photography salable by keeping your subject matter simple. Feature only one thing at a time, or one playing off another, rather than a group of things.

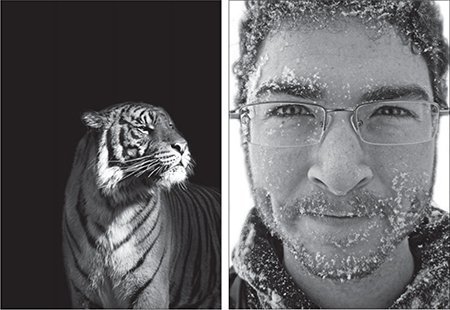

Animals. Both wild animals and pets are perennially popular. Choose handsome and healthy subjects. Keep the background simple so it will enhance, rather than overpower, your subject.

Dramatic landscapes. Shoot landscapes in all seasons, especially with approaching storms, complete with lightning and rolling thunderclouds. If you lean toward Photoshop digital enhancement, take care. Overly enhanced images often have an effect on viewers opposite from what you anticipated. The effects of ice storms are always popular, as are New England pathways in the fall, and rural snow scenes.

Nostalgia. Snap a photo of a rustic pioneer’s cabin or an antique front-porch swing; historical sites with patriotic significance, such as Paul Revere’s home or Francis Scott Key’s Fort McHenry are popular; compose still lifes containing memorabilia such as Civil War weapons or whaling ship artifacts.

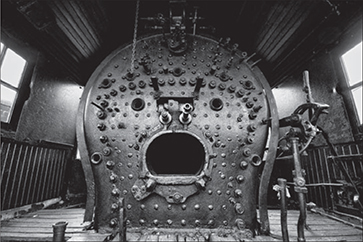

Abstracts. Your pictures can range from bold, urban shadow patterns to the delicate network of filaments in a spider’s web. Abstracts, whether analog or digital, lend themselves well to waiting rooms, attorneys’ offices and professional buildings as well as homes.

Sports. Capitalize on the nation’s avid interest in sports and sports personalities. Close-ups sell best. Scenes of sporting events lend themselves to game rooms and family playrooms. Keep in mind that many sports teams aggressively guard their perceived right to market images of their teams and players exclusively.

Patriotism. These appeal to government (state, county and federal) offices as well as to corporations.

Portraits. Model releases are necessary. Close-ups sell best. Exotic, interesting, quizzical, yet pleasant (Mona Lisa) faces sell to legal suites and corporation offices.

Erotic. Eroticism finds a market in private clubs. Subject matter can range from newsstand pornography to esoteric nude studies.

Industrial. Sell your best industrial scenes to engineers’ offices. Pictures should be well composed, visually exciting but easy to look at, and of high technical quality. Visually appealing abstract patterns, close-ups of computer chips, laborers in meaningful work or factories at sunset after a fresh rainfall are appealing. De-emphasize the negative aspects of industry.

Underwater. The quietude and exotic nature of underwater scenes are appealing to consumers. For a how-to book on underwater photography, read Jim Church’s Essential Guide to Nikonos Systems by Jim Church or The Underwater Photography Handbook by Annemarie and Danja Köhler.

WHAT TO CHARGE

Prices depend on whether you sell in volume or individually. In either case, the buying public will pay about $50 for an 11" × 14" (28cm × 36cm) and $30 for an 8" × 10" (20cm × 25cm), after markup. Before you decide on your own price, see what the local department stores are getting for similar decor photography. Also check out fees online and in catalogs from sellers of fine art and decor photography.

Limited editions are another question: Can you demand a higher fee? Of course, if you keep a couple prints for the grandchildren, they just might become heirs to very valuable prints. How do you limit the edition? As with other printmaking (silkscreen, digital, etching or lithography), you usually destroy the original after making one hundred to five hundred prints.

What should you charge for limited editions? Keep in mind the professional artist who once said, “If you are going to price your watercolor at $15, you’ll find a $15 buyer. If you price it at $75, you’ll find a $75 buyer. And if you price it at $850, you’ll find an $850 buyer. Just takes time.” The going rate for a 16" × 20" (41cm × 51cm) color limited-edition photograph is between $100 and $175 with a basic frame.

BLACK AND WHITE OR COLOR?

Black-and-white prints often sell well as decor photography if they are sepia toned. However, color probably has the edge over black and white. As a stock photographer, you’ll also want to market your color through regular publishing channels, and they generally require digital high-resolution files. If you so wish, you can buy a film scanner, software and a professional-grade printer, and print your own images. It’s a lot of work, but it might save you a buck or two in the long run, and you will have greater control and more opportunities than if you farmed the printing out. The initial investment can be rather large though.

DIGITAL CONSIDERATIONS

There’s no denying that film-based decor art (analog) is fast becoming an artifact. As digital technology moves into the decor field, less and less analog (film) prints will be produced, making them a valuable commodity. However, in the short term, digital production will bring quicker monetary reward. It’s easier, quicker, and, produced with quality equipment, cheaper. Another advantage: Rather than have a decor print produced at great expense via lithography, an equally fine print can now be made through “on demand” short-run technology.

SIZE

If you sell your prints on a single-sales basis, you’ll find that the larger 16" × 20" print (41cm × 51cm) (and higher fee) will result in more year-end profit than smaller 11" × 14" (28cm × 36cm) or 8" × 10" (20cm × 25cm) prints (and lower fees). On the other hand, if you go to multiple sales and smaller prints, and you aim for the volume market in high-traffic areas such as arts-and-crafts fairs or shopping malls, you can be equally successful.

FRAMES

Framing or matting your print definitely enhances its appearance and salability. You can improve some prints by using textured or silk- finish print surfaces. Dry-mounting materials, glass and hinge mattes are available everywhere. Some processors offer protective shrink wrap (a thin, close-fitting, clear plastic covering). Check photography magazines for advertisements for do-it-yourself frames. How-to series often are featured in photo and hobby-and-craft magazines; search the Web or consult your library’s Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature for back issues. If all else fails, team with a frame shop and split the profits.

PROMOTION

This is the key to your selling success. If you’ve sold a series of prints to one bank in town, let the other banks know about your decor photography. Look for ways and places to exhibit your pictures often. Sign your prints or mattes for added promotion and referrals. Offer your services as a guest speaker or local TV talk-show guest. Produce brochures, flyers or catalogs of your work. Here are two helpful books: The Executive’s Guide to Handling a Press Interview by Dick Martin and DIY PR: The Small Business Guide to “Free” Publicity by Penny Haywood. (For more hints on self-promotion, see chapter ten.)

LEASING

Start your own leasing gallery. Businesses know that leasing anything can be charged against expenses. By leasing decor photos to corporations, small businesses or professionals, you’ll get more mileage out of your photos.

Decor-photography and stock photo agencies both offer opportunities as outlets for your Track A pictures. The main message of this chapter has been to emphasize that success with these two secondary marketing channels takes research and time on your part. If you’re willing to give it what it takes, you can realize rewards.