3

Finding Your Corner of the Stock Photography Market

FIRST, FIND YOURSELF

Who are you? Photographers who are successful in selling their pictures have learned this marketing secret: Know thyself. That is, know your photographic strengths and weaknesses before you begin marketing your pictures.

You want to find your corner of the market. First, though, you must find out who you are, photographically. You can do that by completing the following simple exercise.

Photographically . . . Who Am I?

Save a Sunday afternoon to fill out this section—it will help you avoid spinning your wheels, which you’d be doing if you jumped into photomarketing without having the information in this chapter. If you’re reading this book a second time because your stock photography enterprise is sputtering and coughing and you’re wondering what went wrong, read this chapter carefully. Many photographers fail to do so and then fail. As the saying goes, “When all else fails, read the directions.”

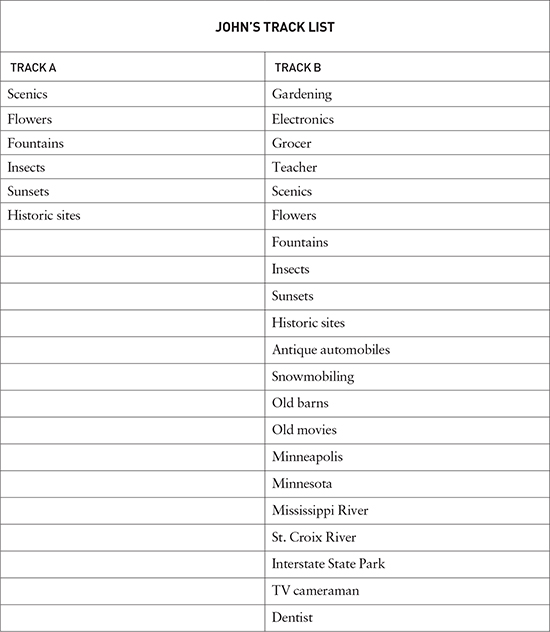

Take a sheet of paper and make two columns like the ones in Figure 3-1. Head the column on the left, Track A; the column on the right, Track B. The columns can extend the length of the page, or pages, if necessary.

Next, fill in the Track B column with one-line answers (in no special order) to these questions:

- What is the general subject matter of each of the periodicals you subscribe to, or would like to subscribe to (or receive free)? (For example, if you subscribe to Today’s Pilot, you would write “aviation.”) Write something for each magazine. Do you welcome catalogs in the mail? What are the subject matters? Write them down.

- What is your occupation? (If you’ve had several, list each one.) Also include careers you’d like to pursue or are studying for or working toward.

- When you’re on a photo-taking excursion, what subjects do you enjoy taking the most (e.g., rustic buildings, football, celebrities, sunrises, roses, waterfalls, butterflies, fall foliage, children, puppies, Siamese cats, hawks, social statements, girls)? Use as many blanks as you wish. The order is unimportant.

- List your hobbies and pastimes (other than photography).

- If you were to examine all of your slides, prints and digital files, would you find threads of continuity running through the images? (For example, you might discover that you often photograph horses, train stations, rock formations, physical fitness buffs, minority groups and so on.)

- What are your favorite armchair interests? (For example, if an interest is solar energy, astronomy or ancient warfare, write it down.)

- What is the city nearest you with a population of more than 500,000?

- What state or province do you live in?

- List any nearby (within a half-day’s drive) geographical features (e.g., ocean, mountains, rivers) and human-made interests (e.g., iron or coal mine, hot-air-balloon factory, dog-training school).

- What specialized subject areas do you have ready access to? (For example, if your neighbor is a bridge builder or a ballerina, a relative is a sky diver, or your friend is an oil-rig worker, list the person’s subject area.)

Figure 3-1

Now, if the list in Track B includes any of the following, draw a line through them: landscapes, birds, scenics, insects, plants, wildflowers, major pro sports, silhouettes, experimental photography, artistic subjects (such as the art photography in photography magazines), abstracts (such as those seen in photoart magazines and salons), popular travel spots, monuments, landmarks, historic sites, cute animals.

Transfer all of the subjects that you just drew a line through to Track A.

You’ll find your best picture sales possibilities in Track B. Track A is a high-risk marketing area for you and you will likely spend a lot of time getting no results should you decide to market these photographs. Most photographers have spent a great deal of their time photographing in the Track A area, and because it’s so popular, photo buyers can find these pictures easily in micro-stock agencies and from other online sources (more about micro-stock in chapter twelve).

When you get off Track A and onto Track B, you’ll stop wasting time, postage and materials. You’ll get published, receive recognition for your specializations in photography and deposit checks. Let’s examine the Track B and Track A of one hypothetical photographer, John, whose interests are listed in Figure 3-1.

1.John subscribes to magazines dealing with gardening, electronics and antique automobiles. Not only do these reflect John’s interests, but the combined total of fees paid for photographs purchased by magazines and books in these three areas can exceed $150,000 per month. Yet John has put most of his picture-taking energy and dollars into Track A pictures, which have limited marketing potential for him because of the law of supply and demand.

2.John’s occupation is grocery store manager. The trade magazines in this area spend about $20,000 per month for photography. John could easily cover expenses to the national conventions each year, plus add an extra vacation week at the convention site, with income generated by his camera.

John is a former teacher and retains his interest in education. His experience gives him the insight and know-how to capture natural photographs of classroom situations. Such photos are big sellers to the education field, denominational press and textbook industry. A conservative industry estimate of the dollars expended each month for education-oriented pictures is $800,000.

3.In his picture-taking excursions John usually concentrates on scenics, flowers, fountains, insects, sunsets and historic sites. These all have limited marketability with the big agencies and top magazines for the independent freelancer without a track record. However, John could place some of these Track A pictures in stock agencies for periodic supplementary sales. A stock agency that specializes in insects, for example, would be interested in seeing the quality of John’s pictures. Some of John’s other Track A pictures belong in different stock agencies. (Chapter twelve tells how to research which agencies are right for which pictures on your Track A list.)

4.John’s favorite hobby is antique cars. He can easily pay for trips to meetings and conventions through judicious study of the market needs for photography involving antique cars. John also lists snowmobiling as a hobby. Publications dealing with winter fun in season spend more than $80,000 a month on photography.

5.John finds that he photographs picturesque old barns every chance he gets. The market is limited (Track A). One day he may produce a book or exhibit of barn pictures, but it will be a labor of love.

6.His armchair interest is old movies, which has no marketing potential unless placed in a specialized photo agency.

7, 8.Nearest city: Minneapolis. State: Minnesota. (Chapter eleven will explain how to capitalize on your travel pictures.)

9.The Mississippi and St. Croix rivers are nearby, plus several state parks (see chapter eleven).

10.John’s neighbor is a TV cameraman. John could get specialized access to TV operations and be an important source to photo buyers who need location pictures dealing with the TV industry. John has access to the field of dentistry through his brother, a dentist. Publications in each of these areas easily spend a combined $20,000 per month for pictures.

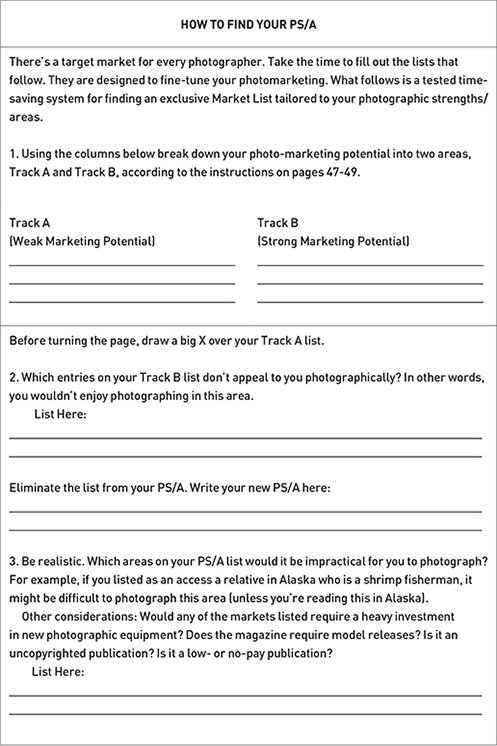

YOUR PS/A (PHOTOGRAPHIC STRENGTH/AREAS)

Let’s take a closer look at Tracks A and B.

Track A: The Prognosis Is Guarded

These are the areas of formidable competition. Track A pictures are used in the marketplace all right, but it’s a closed market. Photo buyers have tons of these photos in inventory, they locate them easily from their favorite top pros, they click one from a clip-art disc or an online service, or they contact a stock agency that has thousands upon thousands of these photos to select from. If you want to concentrate your efforts in the Track A area of photography, I suggest you stop reading right here, because you’ll need to invest every minute of your time into making a go of it and even then you’d be hard pressed to make any headway. These days there are a plethora of agencies online that license Track A type photographs for as little as one dollar per photo.

If you’re not planning to concentrate on Track A pictures, but you still want to take them, one solution is to put your Track A shots into a stock photo agency and then not worry about how often they sell for you. I recommend against this though as it can be a huge drain on your time and energy. Every once in a while, you may get a nice surprise check. (Chapter twelve shows you how to determine which agencies are for you.) A second solution is to turn to producing decor photography (again, see chapter twelve). Keep in mind, though, that you can’t expect either of these solutions to result in regular sales. Decor photography is a labor of love; the big moneymaker at a stock agency is the agency director. Practically speaking, your forte and solid opportunity for immediate and consistent sales—in other words, your strong marketability areas—remain on Track B.

Track B: The Outlook Is Bright

Take time to completely fill out Track B, and you’ll find that you’ve sketched a picture of who you are photographically. This list is your PS/A, your Photographic Strength/Areas. You have vital advantages in these areas. You offer a valuable resource to photo buyers in these specialized subjects. You have access and an informed approach to pictures in these areas that many photographers do not have. Your competition in marketing Track B pictures is manageable. Throughout this book, I’ll constantly refer to your PS/A, your Track B list. You are already something of an expert in many of these Track B areas, and the subject matter appeals to you. Not all of your interests, of course, lend themselves 100 percent to photography, but you will be surprised how many do. For example, chess has spawned few periodicals that require pictures. However, pictures of people playing chess have varied applications—concentration, thinking, competition—good illustration possibilities for textbooks or for educational, sociological or human-interest magazines.

Figure 3-2

By purchasing more and more of your stock photos, photo buyers in the Track B markets will encourage you to submit pictures. Gradually you’ll receive higher fees—and eventually assignments. Pretty soon, you’ll consider graduating to higher paying markets in your specialization area(s). Your efforts and sales in the nuts-and-bolts areas of Track B may one day even justify the time you still may wish to give to Track A photos, which actually cost you money to try to market.

Within your PS/A you will become a valuable resource to photo buyers. I specialize in photographing law enforcement and prisons. It happens regularly that I will get a call from a photo buyer looking for an image but not knowing what they’re looking for. They might know that they need a photo of meth amphetamine to illustrate a textbook, but they don’t know what meth looks like. I do and I can submit a variety of photos showing various shapes, textures, colorations, etc. In these cases I’m an expert and the photo buyer relies on me to assist with finding the right photo. This is what I talk about when I say that you are, or will become, a valuable resource to the photo buyers you work with.

Throughout this book, when I refer to you, the photographer, I mean for you to adapt what I’m saying to your particular photographic strengths and approaches. Refer again to the photographic picture of yourself that you’ve outlined on Track B. When I say you, I won’t mean me, or any other reader of this book. Another photographer would fill out this chart differently. She also would be an important resource to certain editors, but rarely would the two of you compete for the attention of the same photo buyers. Your task will be to find your own mix of markets, based on the areas you like and know best, and then hit those markets with pictures they need.

This approach eliminates the drudgery associated with the admonition we often read in books and hear at lectures: “Study the markets!”

When I first began marketing my photographs, I also heard “Study the markets!” I’ve always associated the word study with tedium, but it was something I needed to do, if only ever so briefly. I was writing an article for a Swedish magazine about street gangs in the U.S. When I started to look for stock photos to illustrate the article, I realized very few were available and those that were were either dated, plain bad or both. I’ve had a lot of experience writing about law enforcement and prisons all over the world, so I was already an expert on the topics and they were indeed what my personal PS/A were made up of. The rule of thumb is for you to have some connection to the subjects you photograph. It rang true then and it rings true today: If it wasn’t in my PS/A, I had no business either studying it or photographing it.

The Majors and the Minors

Do you know any successful photographers? Success eludes concrete definition. We all know that it’s irrelevant to judge people’s success by their net worth, where they live or the fame they have attained. When I refer to success in this book, interpret it not in terms of some stereotypical level of achievement, but in terms of the goals that are meaningful to you.

The major markets for your stock photos may not necessarily be the major markets for the stock photographer next door. Your neighbor’s major markets may be your minor markets.

Will you have to change your lifestyle or your photography to apply the marketing principles in this book? Not at all. Moreover, breaking in won’t put a dent in your pocketbook. Your major markets need not be in New York: They might be in your backyard.

The length of your Track B list will give you a good idea of the breadth of the market potential for your photography. Some stock photographers thrive in a very limited marketplace. Others find it necessary, because of the nature of their photographic interests, to seek out many markets. The personnel in the publishing world stay in a state of flux. New photo editors come and go, but the theme of the publishing house generally remains the same. As long as your collection of photos matches that theme, you have a lifelong market contact with that publishing house.

How to Use the Reference Guides, Directories and the Internet

Once you know your photographic strengths, you’ll find your corner of the market more easily. Several excellent market guides exist that will point you in the right direction. Keep in mind that, because of publishing lead time, directories, even telephone directories, are up to one year older than the date on the cover. Use your directories to give you a general idea of potential markets for your photographic strengths. For specific names, titles, updated addresses and phone numbers, keep your directories current by making personnel changes whenever you learn of them through your correspondence,

phone calls, newsletters or online resources.

Treat your directories like tools, not fragile glassware. Keep them handy, scribble in them, paste in them, add pages or tear pages out. Your directories are a critical resource for moving forward in your photomarketing. If you’re computerized, begin to maintain a photo buyer database. (See chapter seventeen for ideas on how software can help you organize your Market List.)

You can find outdated directories at your local library’s spring book sale. Usually the cost of a seventy-five-dollar directory is fifty cents to a dollar. However, don’t automatically assume that addresses, names of photo editors, phone numbers, fax numbers and so on are still accurate. Consult an up-to-date directory for that information. Outdated directories can be useful for checking to see how long a business has been around.

| DIRECTORIES |

|---|

| Advertising REDBOOKS |

| P.O. Box 1514, Summit, NJ 07902 |

| American Book Trade Directory |

| R.R. Bowker Co., 630 Central Ave., New Providence, NJ 07974 |

| www.bowker.com |

| American Hospital Association Directory |

| One North Franklin, Chicago, IL 60606 |

| www.aha.org |

| ASMP Stock Photography Handbook |

| 150 N. Second St., Philadelphia, PA 19106 |

| www.asmp.org |

| Association for Education Communications Technology |

| 1025 Vermont Ave. NW, Suite 820, Washington, DC 20005 |

| Audio Video Market Place |

| R.R. Bowker Co., 630 Central Ave., New Providence, NJ 07974 |

| www.bowker.com |

| Bacon’s Publicity Checker |

| Bacon’s Publishing Company, 332 S. Michigan Ave., Chicago, IL 60604 |

| Broadcast Interview Source |

| 2233 Wisconsin Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20007 |

| Canadian Almanac & Directory |

| Grey House Publishing Canada, 555 Richmond St. W, Suite 512, Toronto, Ontario M5V 3B1 |

| Canada |

| www.greyhouse.ca |

| Cassell’s Directory of Publishing in Great Britain, the Commonwealth and Ireland |

| Villiers House 41/47, Strand, London WC2N 5JE England |

| Encyclopedia of Associations |

| Gale Group |

| 27500 Drake Road, Farmington Hills, MI 48331 |

| www.galegroup.com |

| Gebbie Press All-In-One Media Contact Directory |

| P.O. Box 1000, New Paltz, NY 12561 |

| www.gebbieinc.com |

| IMS Directory of Publications and Broadcast Media |

| Gale Group, 27500 Drake Road, Farmington Hills, MI 48331 |

| www.galegroup.com |

| Library and Book Trade Almanac |

| R.R. Bowker Co., 630 Central Ave., New Providence, NJ 07974 |

| www.bowker.com |

| Literary Market Place |

| www.literarymarketplace.com |

| O’Dwyer’s Directory of Public Relations Firms |

| J.R. O’Dwyer Co., 271 Madison Ave., New York, NY 10016 |

| www.odwyerpr.com |

| Patterson’s American Education |

| Educational Directories Inc., P.O. Box 68097, Schaumburg, IL 60168 |

| Photographer’s Market |

| North Light Books |

| 10151 Carver Road Suite 200, Blue Ash, OH 45242 |

| www.northlightshop.com |

| SATW (Society of American Travel Writers) Member Directory |

| 50 S. Main St., Suite 200, Naperville, Illinois 60540 |

| www.satw.org |

| Ulrichsweb Global Serials Directory |

| www.ulrichsweb.com |

| The World Almanac and Book of Facts |

| www.worldalmanac.com |

| Writer’s Market |

| Writer’s Digest Books, 10151 Carver Road Suite 200, Blue Ash, OH 45242 |

| www.writersdigest.com |

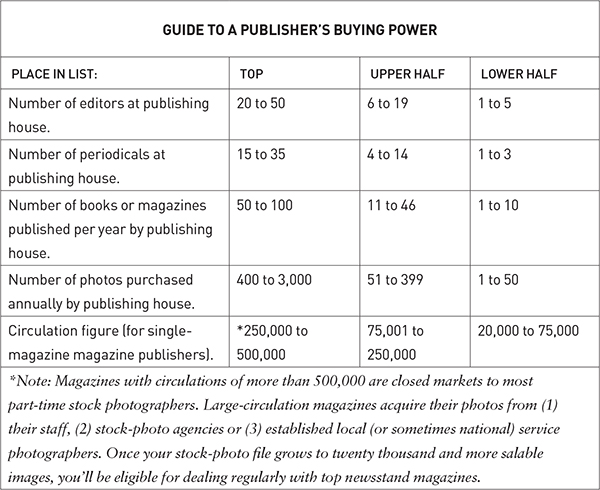

Table 3-1 lists the names and addresses of published directories. You’ll find most of these at any large metropolitan library, and your local public library or a college library in your area will stock many of them.

Which directories are best for you? You’ll find out by matching the subject categories in your Track B list with the market categories covered by the different directories. The most popular directory among newcomers to stock photography is Photographer’s Market (published by North Light Books), an annual directory that lists two thousand up-to-date markets including magazine and book publishers. This directory not only tracks down personnel changes in the industry, but it also lists the fees photo buyers are willing to pay for stock photos and, in some cases, assignments.

Using Your Local Interlibrary Loan Service

Some directories may be too expensive for you. They also may be too expensive for your community or branch library. Ask the librarian to borrow such a directory through the interlibrary loan service (or its equivalent in your area). If the book isn’t available at a regional library, the service will locate it at the state level. It generally takes two weeks to get a book. Since the books you order will be reference manuals, your library will probably ask that you use them in the library. However, you can photocopy the pages you’ll need, thanks to the fair use doctrine of the U.S. Copyright Act (revised 1978). (See chapter fifteen for more on copyright.)

Using the Internet

Internet search engines such as Google (www.google.com), Lycos (www.lycos.com), Ask (www.ask.com), Yahoo (www.yahoo.com) and Dogpile (www.dogpile.com) can be invaluable when it comes to building your Market List. If you key “gardening magazines” into Google, for instance, chances are you’ll be amazed at the results. If you don’t have access to the Internet, you can use computers with Internet access at your local college or library.

Chart Your Course . . . Build a Personalized Market List

Now that you’ve defined your photographic strengths and focused in on accessible subject areas, you’re ready to chart your market course.

Successful businesspeople in any endeavor aim to reduce the possibility of failure by reducing or eliminating no-sale situations. Why attempt to sell your pictures to a market where the no-sale risk is high? By using the procedure that follows, you will build a no-risk Market List and begin to see your photo credit line in national circulation.

Consult all of the directories available to you, and build a list of potential markets for your material by combing through the categories that match your photographic strengths. This might take several evenings of effort, but the investment of time is worth it.

I have a Market List I have built over the years since I moved to the U.S. from Sweden in 1998. I make sure it is up to date all the time. This Market List is like a treasure: Every time I use it I get a great response from almost everyone on the list.

SETTING UP YOUR MARKET LIST

Make a list in Word or similar. Include on your list information about the photo buyers you deal with at each market—title: nickname, phone, fax, e-mail address, former position or title, plus a note or two about their photo-buying procedures, fee range, preferences, dislikes and assignment possibilities. Keep code designations of your promotional mailings to them (see chapter ten) and changes of address, title or personnel up to date.

Chances are that you’ll need more space rather than less space in your database, so choose systems wisely. Be it index cards or software, pick a system that’s easily upgradeable when you need the extra space or additional capabilities. Your system should allow you to delete, repair (e.g., make changes of address or spelling corrections) or alphabetically add names easily.

You can start your personal Market List from the directories, but you can discover additional markets for your pictures at newsstands, doctors’ waiting rooms, reception rooms and business counters.

Your list is now tailored to your exact areas of interest. If you have several areas of interest, should you make several lists? My advice would be to keep one master list. Color-code the categories, or use the capabilities of your database software. Then, when you repair or replace a listing, you need do it only once. (For more on record keeping, see chapter thirteen.)

THE SPECIALIZATION STRATEGY

Now that you have charted your course to sail straight for your corner of the market, you’re bypassing the hordes of photographers on Track A, and you’re moving along Track B, where the competition is manageable.

As you work with this system, you will discover that you can define your target markets even more specifically and improve the marketability of your pictures 100 percent through a strategy used by all photographers who are successful at marketing their pictures: the strategy of specialization.

Figure 3-3

We live in an age of specialization. Once we leave school, whether it be high school or medical school, we are each destined to become a specialist in something. In today’s world, with the immense breadth of knowledge, technology and diversification, it’s impossible for one person to be expert in all aspects of even a single chosen field. In our culture, buyers of a person’s services prefer dealing with someone who knows a lot about a specific area rather than with someone who spreads himself too thin.

The same holds true for photo buyers. They know the discerning readers of their specialty magazines expect pictures that reflect a solid knowledge of the subject areas. Understandably, then, buyers seek out photographers who not only take excellent pictures but also exhibit familiarity with and understanding of the subject matter of their publications.

Technical knowledge alone is not sufficient to operate successfully in today’s highly specialized milieu. Marketing people have found that consumers often buy an image rather than a product. Their success at image- creating to sell cars, insurance and beer attests to the power of images to move the buying public. Since most magazines (and to a lesser extent books) are extensions of their advertisers or supporting organizations, photo editors, directed by the publisher’s editorial board, constantly seek out photographs and photographers who can capture the publication’s image in pictures. The image projected in a yachting magazine will be subtly different than that projected in a tennis magazine. The image projected by a magazine called Organic Fruit Growing will be radically different from that projected by one called Chemical Fertilizers Today.

These nuances are important for you to be aware of. (In chapter nine I’ll discuss these nuances further and show you an effective query letter for reaching photo editors.) Go over the list of markets you’ve compiled for yourself. Familiarize yourself with the publications (write for copies or find them at the library) to educate yourself on their individual themes. Often the book or magazine publisher will supply you with photo guidelines. If you can’t get a handle on the image of some of the markets, put them at the bottom of your list. Keep the areas you’re more sure of at the top. You have now fine-tuned your list; you can be more selective in your choices. The top of your list has your target markets, the ones that best reflect who you are photographically, the ones that fall within your personal photomarketing strengths. Editors have specific photo needs, and the sooner you match your subjects and interest areas with buyers who need them, the sooner you’ll receive checks.

You’ll also be building a reputation among the photo buyers who need your specialized photography. Photo buyers pass the word.

KEEPING ON TOP WITH NEWSLETTERS

Another way to discover additional markets for your list and to keep abreast of current market trends is to read the newsletters in the field.

You can find information about photo-oriented newsletters on the Web or at your local library. Sample copies usually are available for less than $5. For names and addresses of the best in the field, see the bibliography on page 313.

Figure 3-4

The Total Net Worth of a Customer

The effort it takes to locate your markets results in far more than a limited series of sales. You are in effect locating sources of long-term annuities. When you use the marketing methods outlined in this book, you’re developing a potential long-term relationship with a portion of your markets or customers, whether they are corporations, public relations firms or publishing houses. Publishing houses particularly lend themselves to a long-term affiliation because of the stability of their focus and emphasis. In my experience ten years is a reasonable average length of time you can expect to stay with a publishing house. Sometimes it’s much longer.

This idea of the long-term value to you of a customer can be stated as the total net worth of that customer to your business. To determine a customer’s total net worth to your specific operation, average your total sales, also factoring in those markets you contact that you don’t achieve sales with. For example, using a worst-case scenario: Taking only low-budget customers and figuring extremely conservatively that a customer may last only one year, you find you could spend up to $100 to acquire that one customer and still break even. (You’d break even because $100 is the net profit you could reasonably expect from one customer for one year at the low-budget level.) Since your promotional package to prospective photo buyers would cost about $1 (an industry average), you could afford to contact one hundred potential customers (100 × $1 =$100). If out of those one hundred that you contact you land two, three or five steady customers, you’re in the black. With experience gained through analyzing your data, you’ll learn how many contacts you need to make, on the average, to land one consistent customer. Then you’ll know the least amount you can afford to spend at the low-budget level to acquire a new customer.

Naturally several contingencies are involved. For example: Does your prospect mailing list match your PS/A? Is your promotional package professional looking? (Consult your mailing package checklist on page 156 in chapter nine.)

If you acquire just one consistent customer (just 1 percent) in your promotional campaign to one hundred prospects, you will break even. If you acquire ten (10 percent), you can make a potential (conservative) net profit of $1,000 for the year, and ultimately $10,000, based on the total net worth of each customer over a ten-year span.

Analyze your own Market List. How many markets have bought from you once, twice, five times, twenty times in one year? What is the average for one year? How many years have they stayed with you? What average net profit do you get from each sale? If you’re just starting out, keep track of this information to refine your educated guesses until you gradually accumulate your averages.

Long-Term Value

I have presented this system conservatively. Actually, if you’re aggressive and confident of the quality of your work and targeted value of your mailing list, you could lose money on your promotional campaigns and still come out ahead. The long-term income from your acquired customers would eventually eliminate the loss you initially experienced in acquiring them.

POSITION YOURSELF

If you’re interested in making money from your photographic talent, you will want to follow a basic business concept: positioning. If your collection of photos is strong in, say, education, position yourself so that you become a valuable resource to editors who are in continual need of education photos. I know photographers who have positioned themselves so well in their specialty area that they can call editors collect.

When you position yourself, you lock yourself into publishing houses that produce visual materials relating to one theme. This may be auto racing, gardening, hang gliding, medicine and so on. When you submit your first selection of photos to such a publishing house, spark the photo buyer to say, “This photographer speaks my language.” Once you sell your first photo to a theme publisher, you will find it much easier to make subsequent sales.

The total net worth principle presents you with a model of your business, a mathematical relationship as to how your business works and what works. Moreover, it provides you with a warning signal before you make a bad decision. Once you have done the tedious initial work of tracking and analyzing your customers, further analysis is easy and simple. A computer will help, and you can use most database and spreadsheet programs to process the information. This total net worth principle will help you guide your business ship with far more precision.