2

What Photos Sell and Re-Sell?

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A GOOD PHOTO AND A GOOD MARKETABLE PHOTO

What kind of photo can you be sure will sell for you—consistently? And what kind of photo will disappoint you—consistently?

You may be surprised at the answer to these two questions. The heart of the matter is that one type is a good photo, and the other type is a good marketable photo. It’s surprising because the good photos seem like they ought to be marketable; we see them everywhere, looking at us from billboards, magazine covers, brochures, advertisements and greeting cards. These good pictures are lovely scenics, beautiful flower close-ups, sunsets and dramatic silhouettes—those excellent Kodak-ad shots and contest winners. These photos also could be called “standard excellent pictures.”

“But why do they consistently ring up no sale when I try to market them?” you ask. Because the ad agencies, graphic design studios and top magazines who use these standard excellent shots don’t need them; 99 percent of the time their photo buyers have hundreds, indeed thousands, of these beauties at their fingertips—in inventory, at their favorite stock photo agencies, or from the list of stock photographers they’ve worked with and know are reliable. Ninety-nine percent of the “good” pictures you see published in major newsstand magazines or in calendars, brochures or posters are obtained from one of those two sources: stock photo agencies or top established professionals.

The established professional usually has a better supply of standard excellent pictures than the average photographer or serious amateur, even though the latter may have been photographing for years. Professionals have work schedules and assignments that afford them hundreds of opportunities to supplement their stock files. The professionals can shoot more easily and less expensively because an assignment already has them in an out-of-the-way, timely or exotic location, and they can piggyback stock-file photos with their original assignments. Getting the same shots could cost you a great deal in travel and operations expense. Moreover, when buyers of these photos want a good photo, they don’t turn to a photographer with a limited—albeit excellent—stock file who’s unknown to them and has a limited or nonexistent track record.

The best place for your standard excellent photos, then, is in a midsized stock agency. You may need to start in one or more small agencies and work your way gradually into a major agency. This, too, is a form of sweepstakes marketing, but chances are that even amid the tough competition (by virtue of the sheer number of photos), you’ll find that a sale now and then nicely complements the sales from your own direct marketing efforts. The key phrase here is now and then. It’s not a case of the checks just rolling in once you put your photos in an agency.

I realize there are a dozen books on the market that report that you can sell the standard excellent picture to buyers. There also are books that assert that you can write a blockbuster novel, write a top-forty hit song and make a hit record that sells a million copies. I don’t doubt that the authors of these books have hit the jackpot themselves or know someone who has. However, you open yourself up to two disadvantages when you attempt to appeal to the common denominator of the public’s taste.

- First, the romance and appeal of commercial stock photography soon fades after you’ve snapped an angle of the Washington Monument or a sunset in Monterey Bay for the twentieth time, likewise with a standard symbol of power (ocean waves), hope (sunlight streaming through rolling dark clouds) and so on.

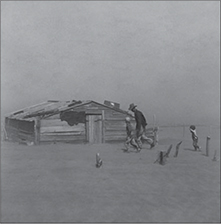

Illustration 2-1.

Illustration 2-2.

The original exhilaration of stock photography diminishes when you realize that you’re following someone else’s tracks, when you know the identical pictures are in other photographers’ files. On the one hand, it can be money in the bank when you snap the standard shot of the Maroon Bells in Colorado, but it’s disheartening to discover tripod marks or chewing gum wrappers in a spot where you had thought you were experiencing a moment of discovery. Eventually you come back to your starting point and say, “There must be more to stock photography than this.”

If you were to continue to snap these exquisite clichés as your standard stock in trade, what would you have after two or three decades? Would a publisher aggressively seek you out to publish an anthology of your work? Not if your photos were cookie-cutter versions of standard subject matter, making you indistinguishable from hordes of other commercial stock photographers.

- The second disadvantage is economic. The law of supply and demand indicates that it’s dangerous to count on consistent sales to the markets that buy the standard “excellents.” The market is so flooded with these pictures—in commercial stock agency catalogs, CD-ROM “click art” and online digital portfolios—that the idea that your particular versions would hit every time, or most of the time, enters the realm of high optimism—admirable perhaps, but not too practical. No viable business can survive on the occasional sale, so even though it might be useful to take the old cliché photo should the opportunity present itself, don’t count on these kinds of images for your bread-and-butter sales.

I like to call these exquisite clichés “unbelievable.” Although the elements of a marketable picture are there, they are missing one major element: believability.

Enduring Images

Look at the two editorial pictures on page 29 (Illustrations 2-1 and 2-2). Can you read into these pictures? Do they evoke a mood? When they were first made in the thirties, few photo buyers considered them blockbusters. Instead, photo buyers at the time probably were purchasing the standard decorative photos of the day. Today, the pictures endure and are included in anthologies. Are you aiming your stock photography activities at pictures that will endure and create long-term value?

If you’ve been spinning your wheels and getting frustrated in your photomarketing efforts, this chapter will be worth the price of this book many times over; it’s a blueprint for the kinds of pictures you can start taking and selling—today.

Good Marketable Photos

What, then, are the good marketable photos that will be the mainstay of your photomarketing success and will supplement your retirement income as well as be an asset to pass on to your heirs? These pictures are the consistent marketing bets—the photos you can count on to be dependable sellers. These photos have buyers with ample purchasing budgets eager to purchase them right away and over and over.

NO-RISK MARKETING

These good marketable pictures are the ones photo buyers need. Let the pictures in the magazines and informational books in your local library and on the websites of these publishers be your guide. These editorial (nonadvertising or noncommercial) photos show ordinary people laughing, thinking, enjoying, crying, working, playing, sharing, helping each other, and building things or tearing them down. The world moves on and on, and our books, magazines and online media provide us with a chronicle. About fifty thousand such photo illustrations are published every day. They are pictures of all the things people do at all ages, in all stations of life, and in all the countries of the world. These pictures are what editors need constantly. These are good, marketable stock photos—the best-sellers. They may not sell for $750 apiece, but if you plan your marketing system wisely, you can easily sell ten for $75 each.

To clarify the difference in your chances of selling these good marketable pictures compared with standard excellent pictures, consider the Los Angeles or Boston Marathon. Out of thousands of dedicated runners, there’s only one winner. The trophy goes to the top professional who practices day in and day out, rain or shine, and who makes running a full-time occupation. Anyone can get lucky, so I can’t deny that you might win the Boston Marathon—that is, you might score with one of your standard excellent pictures in a national magazine. However, for someone just starting out, the odds weigh heavily against you.

The first step, then, toward consistent success in marketing your photographs is to get out of the marathon and start running your own race.

I once asked a photo buyer, “Why do newcomers always submit standard excellent pictures, instead of on-target, marketable pictures?” His answer: “I think the photography industry itself is partly at fault. Their multimillion-dollar instructional materials, their ads, their video programs, are always aimed at how to take the ‘good picture.’ Photographers believe they have reached professional status if they can duplicate that kind of picture.”

Well-meaning advice from commercial stock photographers sometimes adds to this misconception. In their books, seminars and conversations, successful stock photographers sometimes forget how many years they spent paying their dues before they could sell standard “excellents” consistently. Successful people in any field—medicine, theater, professional sports, photography—often dispense advice based on the opportunities open to them at their current status. They fail to put themselves in the shoes of a newcomer who has yet to establish a track record.

In running your own race, you’ll be up against competition, too, but it’s manageable competition. As you’ll discover in chapter three, you’ll target your pictures to specific markets and take pictures built around your particular mix of interests, your expertise and what you have access to.

THE ROHN ENGH AND MIKAEL KARLSSON PRINCIPLE FOR PRODUCING A MARKETABLE PHOTO EVERY TIME

You can discover the secret to producing good, marketable, editorial stock photos in the markets themselves—the books, magazines, periodicals, websites, CD-ROMs, brochures, ads and other entities and materials that the publishing industry produces every day.

Use this test: Tear pages of photographs (editorial photos, not photos in advertisements) from magazines, periodicals, booklets, and so on, and spread them out on your living room floor. Now place copies of your own black-and-white or color prints on the floor, or project your color slides.1 Do an honest self-critique. Do you see a disparity in content and appearance between the published photos and your own work? If so, how could you improve your pictures? If your pictures blend in, matching the quality of the published photos, you’ll be leaps ahead of the competition. The key is to be fully honest with yourself. Compare your photos with the published photos, fair and square.

Next, give yourself a quick course in how to take marketable photos: Select any of the published photo illustrations, and then go out and take photos as similar to them as you can set up. Use a digital camera to give yourself fast, on-the-spot checks for how you can improve your picture quality.

Am I suggesting that you copy someone else’s work? Yes, and if they will admit it, professionals will tell you that’s how they originally learned many of the nuances of good photography. However, the word copy is a no-no in the creative world. (Unfortunately, purists place undue derogatory emphasis on the word. There is a significant difference between when you re-create an idea and when you just copy it. For instance, it’s perfectly okay for you to re-create a photograph that you’ve seen in a magazine. If you scan the same photograph and claim that it’s now your work, however, that’s not okay.) If, because of conditioning, the word copy doesn’t sit well with you, try re-create. Remember, you’re only copying (re-creating) to learn or improve a technique.

When you check the content and style of published photo illustrations, you’ll find that they consistently feature a reasonably close-up view and a bold, posterlike design. Magazine covers are good examples of stock photography.

A stock photo is successful when the viewer can (1) read into it and (2) sense a mood. To enable the viewer to see what’s going on requires a close look. The viewer shouldn’t have to work hard at studying the picture to perceive what it’s trying to say, so a medium or close-up view works best. Bring the main subject or person in close. Most newcomers to stock photography improve their pictures 100 percent when they move toward their subjects for a tighter composition.

Like the background, the composition of your pictures should be simple and uncluttered. Strive for a clean and posterlike design, a picture that conveys in one glance its reason for being. Be careful not to allow the background to steal attention from the main subject in the picture.

Try not to think of yourself as a photographer, but instead as a graphic designer who happens to use photography as his medium. Try also to keep in mind that you make pictures rather than take pictures.

The Principle

This four-step principle is guaranteed to produce marketable photo illustrations every time:

P = B + P + S + I

PICTURE equals BACKGROUND plus PERSON(S)

plus SYMBOL plus INVOLVEMENT.

Most of the successful stock photos you come across in your research will contain these elements. There are always exceptions to the rule, and we’ll go into some of those after we explore the formula in detail. Of course, as we learned in esthetics, all works of art have both form and content. You’re able to learn how to produce the format of a painting, poem, or photograph, but producing the content, the spirit, is another matter. That talent is unique to you.

Step 1: Background. Choose it wisely. Too often a photographer doesn’t fully notice the background until she sees her developed pictures. The background you choose can often make a difference between a sale and no sale. For example, if you are photographing a pilot, don’t just snap a picture by a corner of a hangar that could be in any building. Search the airport area for a background that says “aviation.” Similarly, an office shot could include a desk or computer to set the scene. A stock brokerage could show a wall screen with numbers in the background.

These background clues should be noticeable but not obtrusive, and the picture should not be cluttered with other objects. The background is crucial to how successfully your picture makes a single statement. Your illustration is more dramatic and more marketable if it expresses a single idea—and does it with economy. As you plan your stock photo, ask yourself, “What can I eliminate in this composition while still retaining my central theme?” Simplicity and clarity are always better than hard-to-find clues and subtle suggestions about what an image is supposed to evoke or deliver.

EVOKE A MOOD

Your central theme doesn’t always have to be describable in words; it can be a mood you wish to convey—a feeling that, if expressed with simplicity, actually lends itself to a variety of interpretations by different viewers. This is a marketing advantage to you because if the picture lends itself to, say, ten different moods or interpretations, you’ve increased its marketability ten times.

By eliminating unnecessary distractions, you guide the viewer to a strong response to your photograph. A clean, simple background usually is available to you. Remember, you have 360 degrees to work with. Maneuver your camera position until the background is uncluttered.

Employ your knowledge of design, color and chiaroscuro (the play of darks against lights and vice versa). If the pilot is wearing a light uniform, shift your camera angle to include a dark mass behind him for contrast. If he’s wearing a dark uniform, choose a light background. This technique will give your stock photos a three-dimensional quality.

Step 2: Person(s). Now that you have a suitable background, maneuver your models or yourself (in some cases, you’ll have to do the maneuvering because the models won’t or can’t move for you) so that the background and models are in the most effective juxtaposition. The models themselves must be interesting looking and appealing. Choose them, when possible, with an eye to their photogenics.2

If your pictures will be used for commercial purposes, such as advertising, promotion or endorsement, you will need your models to sign a model release (consent to be photographed). For pictures that will be used for editorial purposes, such as textbooks, magazines, encyclopedias and newspapers, a model release in most cases is not necessary. (See chapters six and fifteen for more on models and model releases.)

Your photos are illustrations, not posed portraits, so the people you show must be engrossed in doing or observing something. We are all people watchers, and stock photos always are more interesting when the people in them are genuinely involved in some activity. An anthropologist once told me, “Watching other humans was probably the first form of entertainment for early man.”

Remember: You are making a picture, not taking one. The only thing you should take is your time.

Step 3: Symbol. In stock photography anything that brings a certain idea to mind is a symbol, sometimes referred to as an icon. Symbols are everywhere in our visually oriented world. They are used effectively as logos or trademarks in business, for example. In a stock photo, a symbol can be anything from a fishing pole to a tractor to a stethoscope. In the case of a pilot, the pilot’s uniform and cap, an airplane, a propeller, a wind sock, are all symbols. Including an appropriate symbol will make your illustration more effective. Use your object symbols as you would a road sign—to tell your viewers where you are. However, be careful that your symbol is not so large or obvious that it overpowers the rest of your photo; symbols are most effective when they’re used subtly. Avoid the temptation to use such mundane symbols as a pitchfork for a farmer, a sombrero for a Mexican musician or a net for an Italian fisherman. The goal is to clue in your viewer to what is going on, but not to knock him over the head with it. Let him experience some discovery as he looks at your picture. Next time you’re perusing pictures in a magazine or book, watch for the “road signs” and note how, and how often, symbols are used in stock photos.

Step 4: Involvement. The people in your photo should be the subject of the picture (showing enjoyment, unhappiness, fear and so on); or they should be interacting, helping each other, working with something, playing with something, and so on; or they should be absorbed in watching or contemplating some object, scene or activity. Marketable photo illustrations have an involvement, a dynamism, about them that’s distinct from the portrait or scenic quality of standard excellent pictures.

Become a Monopoly

“A monopoly?” you ask. “Me, become a monopoly?” My Webster’s tells me that a monopoly is a “commodity controlled by one party . . . ” Translated to our stock photography industry, that means if you have an extensive file on one single subject, you have a minimonopoly.

When photo buyers are facing a deadline and are up against a stone wall trying to locate a specific picture, you become a hero when you can supply them with that highly specific photo.

Monopolies already exist in stock photography. Photographer Flip Schulke has a near-monopoly of photos of Martin Luther King Jr. When photo buyers need photos of the civil rights leader, guess whom they turn to? I myself have a monopoly of photographs of law enforcement and prisons, which means I enjoy frequent sales to book publishers, magazines, newspapers and a wide variety of different websites—anything from police departments and prison agencies to federal agencies and manufacturers of products used by law enforcement or prison officers.

You may already have an emerging monopoly of highly specialized photos: insects, daffodils, table tennis, giraffes and so on.

In the world of commerce, marketing people say, “Find a need and fill it.” In the creative world, we say, “Determine what I love to photograph, and find buyers who need that.” In other words, if wild horses couldn’t pull you away from your avid interest in some subject area, you’ve discovered where you can easily become a monopoly. Why? Because you don’t have to worry about failing at it. You’ll fail sometimes, but you won’t quit. If you really love what you’re doing, you won’t mind failing until you get it right.

Begin now to ask yourself where your interest areas are. If it’s animals, examine your collection. Do you lean toward certain animals? Domestic, wild, North American, European, African, Asian? Be specific. When photo buyers come calling, they’ll be looking for a specific animal (Abyssinian cat, pileated woodpecker, dromedary camel and so on), not animals in general. When photo buyers can target their search, they will avoid large, general stock photo agencies or websites that probably won’t have a deep selection for them anyway. They’ll go to you with your highly specific file with its up-to-date depth of coverage and variety of choices. This approach results in automatically developing an in-depth historical collection. Once you become an expert in your field, photo buyers will find that you can offer them what no big agency can offer: expert advice and topic-specific knowledge.

Because of space and storage considerations, most massive stock agencies throw away or delete outdated pictures. You have the capability to save the photos, let them mature, and feature them later as historical photos.

How do you know when you’ve achieved monopoly status? When you find your marketing posture has switched from an “us-to-them” mode to a “them-coming-to-us” mode, you have achieved it.

You may find that you have three or four monopolies. You can build your files in those areas. Caution: If you develop too many specialties, you’ll land back where you started, being a generalist.

Photos That You Can Read Into—Using the Principle

Illustrations 2-3 through 2-9 show the formula at work.

Symbols can underscore what your photograph is attempting to portray. You will often find objects readily available at the location where you’re photographing. Once you find a nondistracting background, position your model(s) for the best light and so on, then you can add dimension to your photograph with appropriate symbols.

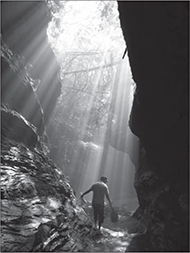

“Involvement” in your photo illustrations sometimes means your models convey serenity. Why is Illustration 2-4 so successful?

B = Background is uncluttered and lends itself to story line.

P = Person is included in story line.

S = Symbol (rays of light) highlights the mood of contemplation or serenity.

I = Involvement is real.

Illustration 2-3.

Illustration 2-4.

Illustration 2-5.

Illustration 2-6.

Illustration 2-7.

Illustration 2-8.

Illustration 2-9.

Illustration 2-10.

THE MISSING LINK

Meaningful pictures happen when you take an active hand in your composition. A snowy road through the forest is picturesque, but when you add the riders fighting against the terrain (the people), a new dimension evolves (Illustration 2-10). Try to think of your photography in these terms—in reverse. Find your symbol or background first, then the other elements: people, involvement and either background or symbol. The resulting photo illustrations will be more marketable.

With just one of the elements in slightly different alignment, or with one or more of the principle elements missing, the photo wouldn’t be a good marketable picture. Remember these elements when taking your photos.

You Are an Important Resource to Photo Buyers

This, then, is what marketable, editorial stock photography is all about. These are the kinds of good marketable pictures that allow you to run your own race.

To restate the problem with generic clichés: While you might hit a calendar or magazine cover with one of these photos now and then, to depend on this type of shot for consistent sales is a mistake. Each buyer has hundreds of this kind of picture in inventory, or she gets buried in these shots if she puts out a request for them. National Geographic, for example, will not let us run a listing for them asking for photos of a bald eagle. They know they would be deluged with bald eagles. The editors know they could find a CD-ROM filled with eagles or shout out the window and have fifty photographers respond with bald eagle photos. However, you will find plenty of National Geographic listings for people interacting with the environment or for wildlife from specific parts of the world.

For every one of those “good pictures” that finally hits, you’ll sell hundreds of good marketable pictures. One sunset at the beach might finally sell to an ad agency for a nice $500, but you won’t sell it again for three or five years. Meanwhile, one picture of a boy chasing a bubble will sell scores of times—and bring more return in the long run.

Don’t rely on wishful thinking. A few stock photographers do get lucky, but by and large, those who are on top and stay there are those who have recognized the overwhelming odds in the marathon route and have switched to what I call “Track B” (see the next chapter). There’s competition in that race, too, but it’s manageable enough to keep you healthily striving for excellence. You may win a blue ribbon for one of your sunsets, but the real judge of marketable photography is the photo buyer who signs the check.

Whether you sell and re-sell your pictures is not up to the photo buyers, but to you, the stock photographer. You control whether you sell or don’t sell—by controlling the content of your pictures.

When you’re out on your next photographing excursion, keep two guidelines in mind:

- Shoot discriminately. Treat each piece of film or each digital image as a finished product that will one day be on a photo buyer’s desk.

- As you prepare to take a shot, ask yourself, “Is it marketable?” (One photographer I know taped this question to the back of her camera.)

I’m not suggesting that you get involved in areas of photography that don’t appeal to you. As I explain in the next chapter, you have assets, photographically, that are individual to you. In the course of this book, I’ll show you how to match your photographic interests with the needs of buyers who are on the lookout for the kind of pictures you can easily supply.

For example, if you live in New Mexico, there’s a lot of picture-taking and selling to be done that a person in another state can’t do and vice versa. Your geographic location is only one advantage that you have over other photographers. You may be into sailing or raising hunting dogs. You may be an armchair geologist. Your hobbies and interests, and your knowledge and your career field, are assets. So I say to persons new in the field of photomarketing, “You can position yourself where the competition is manageable.” With your own PS/A (Photographic Strength/Areas), which we’ll learn to identify in the next chapter, you can be an important resource to buyers who are, right now, waiting for your pictures.

Your aim is to sell the greatest number of pictures with the least amount of lost motion (i.e., unsuccessful submissions). Why take unnecessary risks? Photomarketing is a business. Now that you know the difference between a good picture and a good marketable picture, your sales will start to soar.

A GALLERY OF STOCK PHOTOS

Stock photos and stock photographers come from all walks of life. Here is a selection of pictures from fellow photographers. All of these photographers zero in on their own PS/A and supply their own corner of the market.

Photo by Jamie DeAnne

Photo by Breanna Loebach

Photo by Jamie DeAnne

Photo by Jamie DeAnne

Photos by Carole Albertson

carolealbertsonphotography.com