Chapter 9. Application Integration, Testing, and Tuning

If you’ve been following the steps provided in Chapters 5 through 8, you know your goals; have a diagram of your reputation model with initial calculations formulated; and have a handful of screen mock-ups showing how you will gather, display, and otherwise use reputation to increase the value of your application. You have ideas and plans, so now it is time to reduce it all to code and to start seeing how it all works together.

Integrating with Your Application

A reputation system does not exist in a vacuum; it is small machine in your larger application. There are a bunch of fine-grained connections between it and your various data sources, such as logs, event streams, identity db, entity db, and your high-performance data store. Connecting it will most likely require custom programming to connect the wires between your reputation engine and subsystems that were never connected before.

This step is often overlooked in scheduling, but it may take up a significant amount of your total project development time. There are usually small tuning adjustments that are required once the inputs are actually hooked up in a release environment. This chapter will help you understand how to plan for connecting the reputation engine to your application and what final decisions you will need to make about your reputation model.

Implementing Your Reputation Model

The heart of your new reputation-infused application is the reputation model. It’s that important. For the sake of clarity, we refer to the software engineers that turn your model into operational code as the reputation implementation team and those who are going to connect the application input and output as the application team. In many contexts, there are some advantages to these being the same people, but consider that reputation, especially shared reputation, is so valuable to your entire product line that it might be worth having a small dedicated team for the implementation, testing, and tuning full time.

Appendix A contains a deeper technical-architecture-oriented look at how to define the reputation framework: the software environment for executing your reputation model. Any plan to implement your model will require significant software engineering, so sharing that resource with the team is essential. Reviewing the framework requirements will lead to many questions from the implementation team about specific trade-offs related to issues such as scalability, reliability, and shared data. The answers will put constraints on your development schedule and the application’s capabilities. One lesson is worth repeating here: the process boxes in the reputation model diagram are a notational convenience and advisory; they are not implementation requirements.

Tip

There is no ideal programming language for implementing reputation models. In our experience, what matters most is for the team to be able to create, review, and test the model code rigorously. Keeping each reputation process’s code tight, clean, and well documented is the best defense against bugs and vastly simplifies testing and tuning the model.

Rigging Inputs

A typical complex reputation model, such as those described in Chapters 4 and 10, can have dozens of inputs, spread throughout the four corners of your application. Often implementors think only of the explicit user-entered inputs, when many models also include nonuser or implicit inputs from places such as logfiles or customer care agents. As such, rigging inputs often involves engineers from differing engineering teams, each with their own prioritized development schedule. This means that the inputs will be attached to the model incrementally.

This challenge requires that the reputation model implementation be resilient in the face of missing inputs. One simple strategy is to have the reputation processes that handle inputs have reasonable default values for every input. Inferred karma is an example (see Generating inferred karma). This approach also copes well if a previously reliable source of inputs becomes inactive, either through a network outage or simply a localized application change.

Explicit inputs, such as ratings and reviews, take much longer to implement as they have significant user-interface components. Consider the overhead with something as simple as a thumbs-up/thumbs-down voting model. What does it look like if the user hasn’t voted? What if he wants to change his vote? What if he wants to remove his vote altogether?

For models with many explicit reputation inputs, all of this work can cause a waterfall effect on testing the model. Waiting until the user interface is done to test the model causes the testing period to be very short because of management pressure to deliver new features—“The application looks ready, so why haven’t we shipped?”

We found that getting a primitive user interface in place quickly for testing is essential. Our voting example can be quickly represented in a web application as two text-links: “Vote Yes,” “Vote No,” and text next to it that represented the tester’s previous vote: “(You [haven’t] voted [Yes|No].)” Trivial to implement, no art requirements, no mouse-overs, no compatibility testing, no accessibility review, no pressure to ship early, but completely functional. This approach allows the reputation team to test the input flow and the functionality of model. This sort of development interface is also amenable to robotic regression testing.

Applied Outputs

The simplest output is reflecting explicit reputation back to users—showing their star-rating for a camera back to them when they visit the camera again in the future, or on their profile for others to see. The next level of output is the display of roll-ups, such as the average rating from all users about that camera. The specific patterns for these are discussed in detail in Chapter 7. Unlike the case with integrating inputs, these outputs can be simulated easily by the reputation implementation team on its own, so there isn’t a dependency on other application teams to determine if a roll-up result is accurate. One practice during debugging a model is to simply log every input with the changes to the roll-ups that were generated, giving a historical view of the model’s state over time.

But, as we detailed in Chapter 8, these explicit displays of reputation aren’t usually the most interesting or valuable; using reputation to identify and filter the best (and worst) reputable entities in your application is. Using reputation output to perform these tasks is more deeply integrated with the application. For example, search results may be ranked by a combination of a keyword search and reputation score. A user’s report of TOS-violating content might want to compare the karma of the author of the content to the reporter. These context-specific uses require tight integration with the application.

This leads to an unusual suggested implementation strategy—code the complex reputation uses first. Get the skeleton reputation-influenced search results page working even before the real inputs are built. Inputs are easy to simulate, the reputation model needs to be debugged as well as the application-side weights used for the search will need tuning. This approach will also quickly expose the scaling sensitivities in the system—in web applications, search tends to consume the most resources by far. Save the fiddling over the screen presentation of roll-ups for last.

Beware Feedback Loops!

Remember our discussion of credit scores, way back in Chapter 1? Though over-reliance on a global reputation like FICO is generally bad policy, some particular uses are especially problematic. The New York Times recently pointed out a truly insidious problem that has arisen as employers have begun to base hiring determinations on job applicants’ credit scores. Matthew W. Finkin, law professor at the University of Illinois, who fears that the unemployed and debt-ridden could form a luckless class said:

How do you get out from under it [a bad credit rating]? You can’t re-establish your credit if you can’t get a job, and you can’t get a job if you’ve got bad credit.

This mis-application of your credit rating creates a feedback loop. This is a situation in which the inputs into the system (in this case, your employment) are dependent in some part upon the output from the system.

Why are feedback loops bad? Well, as the Times points out, feedback loops are self-perpetuating and, once started, nigh-impossible to break. Much like in music production (Jimi Hendrix notwithstanding), feedback loops are generally to be avoided because they muddy the fidelity of the signal.

Plan for Change

Change may be good, but your community’s reaction to change won’t always be positive. We are, indeed, advocating for a certain amount of architected flexibility in the design and implementation of your system. We are not encouraging you to actually make such changes lightly or liberally. Or without some level of deliberation and scrutiny before each input-tweak or badge addition.

Don’t overwhelm your community with changes. The more established the community is, the greater the social inertia that will set in. People get used to “the way things work” and may not embrace frequent and (seemingly random) changes to the system. This is a good argument for obscuring some of its details. (See Keep Your Barn Door Closed (but Expect Peeking).)

Also pay some heed to the manner in which you introduce new reputation-related features to your community:

Have your community manager announce the features on your product blog, along with a solicitation for public feedback and input. That last part is important because, though these may be feature additions or changes like any other, oftentimes they are fundamentally transformative to the experience of engaging with your application. Make sure that people know they have a voice in the process and their opinion counts.

Be careful to be simultaneously clear—in describing what the new features are—and vague in describing exactly how they work. You want the community to become familiar with these fundamental changes to their experience, so that they’re not surprised or, worse, offended when they first encounter them in the wild. But you don’t want everyone immediately running out to “kick the tires” of the new system, poking prodding and trying to earn reputation to satisfy their “thirst for first.” (See Personal or private incentives: The quest for mastery.)

There is a certain class of changes that you probably shouldn’t announce at all. Low-level tweaking of your system—the addition of a new input, readjusting the weightings of factors in a reputation model—can usually be done on an ongoing basis and, for the most part, silently. (This is not to say that your community won’t notice, however; do a web search on “YouTube most popular algorithm” to see just how passionately and closely that community scrutinizes every reputation-related tweak.)

Testing Your System

As with all new software deployment, there are several phases of testing recommended: bench testing, environmental testing (aka alpha), and predeployment testing (aka beta). Note that we don’t mean web-beta, which has come to mean deployed applications that can be assumed, by the users, to be unreliable; we mean pre- or limited deployment.

Bench Testing Reputation Models

A well-coded reputation model should function with simulated inputs. This allows the reputation implementation team to confirm that the messages flow through the model correctly and provides a means to test the accuracy of the calculations and the performance of the system.

Rushed development budgets often cause project staff to skip this step to save time and to instead focus the extra engineering resources on rigging the inputs or implementing a new output—after all, nothing like real data to let you know if everything’s working properly, right? In the case of reputation model implementations, this assumption has been proven both false and costly every single time we’ve seen it deployed. Bench testing would have saved hundreds of thousands of dollars in effort on the Yahoo! Shopping Top Reviewer karma project.

Besides accuracy and determining suitability of the model for its intended purposes, one of the most important benefits of bench testing is stress testing of performance. Almost by definition, initial deployment of a model will be incremental—smaller amounts of data are easier to track and debug and there are less people to disappoint if the new feature doesn’t always work or is a bit messy. In fact, bench testing is the only time the reputation team will be able to accurately predict the performance of the model under stress until long after deployment, when some peak usage brings it to the breaking point, potentially disabling your application.

Do not count on the next two testing phases to stress test your model. They won’t, because that isn’t what they are for.

Professional-grade testing methodologies, usually using scripting languages such as JavaScript or PHP, are available as open source and as commercial packages. Use one to automate simulated inputs to your reputation model code as well as to simulate the reputation output events of a typical application, such as searches, profile displays, and leaderboards. Establish target performance metrics and test various normal- and peak-operational load scenarios. Run it until it breaks and either tune the system and/or establish operational contingency plans with the application engineers. For example, say that hitting the reputation database for a large number of search results is limited to 100 requests per second and the application team expects that to be sufficient for the next few months—after which either another database request processor will be deployed, or the application will get more performance by caching common searches in memory.

Environmental (Alpha) Testing Reputation Models

After bench testing has begun and there is some confidence that the reputation model code is stable enough for the application team to develop against, crude integration can begin in earnest. As suggested in Rigging Inputs, application developers should go for breadth (getting all the inputs/outputs quickly inserted) instead of depth (getting a single reputation score input/output working well). Once this reputation scaffolding is in place, both the application team and the reputation team can test the characteristics of the model in it’s actual operating environment.

Also, any formal or informal testing staff that are available can start using the new reputation features while they are still in development allowing for feedback about calculation and presentation. This is when the fruits of the reputation designer’s labor begin to manifest: an input leads to a calculation leads to some valuable change in the application’s output. It is most likely that this phase will find minor problems in calculation and presentation, while it is still inexpensive to fix them.

Depending on the size and duration of this testing phase, initial reputation model tuning may be possible. One word of warning though: testers at this phase, even if they are from outside your formal organization, are not usually representative of your post-deployment users, so be careful what conclusions you draw about their reputation behavior. Someone who is drawing a paycheck or was given special-status access is not a typical user, unless your application is for a corporate intranet.

Once the input rigging is complete and placeholder outputs are working, the reputation team should adjust its user-simulation testing scripts to better match the actual use behavior they are seeing from the testers. Typically this means adjusting assumptions about the number and types of inputs versus the volume and composition of the reputation read requests. Once done, rerun the bench tests, especially the stress tests, to see how the results have changed.

Predeployment (Beta) Testing Reputation Models

The transformation the predeployment stage of testing is marked by at least two important milestones:

The application/user interface is now nominally complete (meets specification); it’s no longer embarrassing to allow noninsiders to use it.

The reputation model is fully functional, stable, performing within specifications, and is outputting reasonable reputation statement claim values, which implies that your system has sufficient instrumentation to evaluate the results of a larger scale test.

A predeployment testing phase is important when introducing a new reputation system to an application as it enables a very different and largely unpredictable class of user interactions driven by diverse and potentially conflicting motivations. See Incentives for User Participation, Quality, and Moderation. The good news is that most of the goals typical for this testing phase also apply to testing reputation models, with a few minor additions.

Performance: Testing scale

Although the maximum throughput of the reputation system should have been determined during the bench-testing phase, engaging a large number of users during the beta test will reveal a much more realistic picture of the expected use patterns in deployment. The shapes of peak usage, the distribution of inputs, and especially the reputation query rates should be measured and the bench tests should be rerun using these observations. This should be done at least twice: halfway through the beta, and a week or two before deployment, especially as more testers are added over time.

Confidence: Testing computation accuracy

As beta users contribute to the reputation system, an increasingly accurate picture of the nature of their evaluations will emerge. Early during this phase the accuracy of the model calculations should be manually confirmed, especially double-checking an independently logged input stream against the resulting reputation claim values. This is an end-to-end validation process, and particular attention should be paid to reputation statements that contain inputs that were reversed or manually changed (due to abuse mitigation or other circumstances). Once a reputation model is in full deployment, this verification process will become significantly more expensive, so the beta test is usually the last chance to cheaply find bugs and conversely reinforce confidence in the system.

Application optimization: Measuring use patterns

Reputation systems change the way applications display content. Those changes add elements to the user interface that require additional space and new user behavior learning, and change the flow of the application significantly. A good example of this effect is when search URL reputation (page ranking) replaced hand-built directories as the primary method for finding content on the Web.

When a reputation-enabled application enters predeployment testing, tracking the actions of users—their clicks, evaluations, content contributions, and even their eye movements—provides important information to optimize the effectiveness of the model and the application as a whole.

Feedback: Evaluating customer’s satisfaction

Despite our focus on measuring the performance and flow of user interaction, we’d like to caution that pure quantitative testing can lead to faulty conclusions about the effectiveness of your application, especially if the metrics are not as positive as you expected. Everyone knows that when metrics are bad, all the tell you is that you’ve done something wrong, not what it is. But that is also often true for good metrics—a lot of page-views doesn’t always mean you have a healthy or profitable product. Sometimes it’s quite the contrary, controversial objects generate a lot of heat (in the form of online discussion) but can create negative value to the provider.

In the beta phase, explicit feedback is required to help understand how users perceive the application, especially the reputation system. Besides multiple opt-in feedback channels, such as email or a message boards, guided surveys are strongly recommended. In our experience, opt-in message formats don’t accurately represent the opinions of the largest group of users—the lurkers—those that only consume reputation and never explicitly evaluate anything. At least in applications that are primarily advertising supported, the lurkers actually produce the largest chunk of revenue.

Value: Measuring ROI

During the predeployment phase the instrumentation is used to regularly measure the effect on revenue and/or other critical success metrics, such as engagement and customer satisfaction. After deployment the daily, weekly, and monthly reports of these business metrics will become the bible for driving the application and model designs forward, so getting them established during this phase is critical to getting management to understand why the investment in reputation is worthwhile. The beta test phase will not demonstrate that reputation has been successful/profitable, but it will establish the means for determining when it becomes so.

Tuning Your System

Sometime in the latter half of the testing phase, the reputation system begins to operate sufficiently well enough to gauge the general effect it will have on the application and early indications of its likely success against the original goals. This is when the ongoing process of reputation model tuning can begin.

Tuning for ROI: Metrics

The most important thing the reputation team can do when implementing and deploying a reputation system is to define the key metrics for success. What are the numerical measures that a reputation-enabled application is contributing to the goals set out for it? For each measure, what are the target values? Is there a predicted lift in user contributions? Should there be more page-views? Is there an expected direct effect on product revenues? Is the model expected to decrease customer care costs? By how much? All of these metrics allow both the application and reputation teams to identify areas for tuning. Sometimes just the application will need to be adjusted, other times just the model will, and (especially early on) sometimes it will all need tuning.

Certainly the reputation team should have metrics for performance, such as the number of reputation statement writes per second and a maximum latency of such-and-such milliseconds for 95% of all reputation queries, but those are internal metrics for the system and do not represent the value of the reputation itself to the applications that use it.

Every change to the reputation model and application should be measured against all corporate and success-related metrics. Resist the desire to tune things unless you have a specific goal to change one or more of your most important metrics.

Model tuning

Initially any moderately complex reputation model will need tuning. Plan for it in the first weeks of the post-deployment period. Best guesses at weighting constants used in reputation calculations, even when based on historical data, will prove to be inaccurate in the light of real-user interaction.

Tip

Tune public reputation, especially karma, as early as possible.

This does two useful things:

If the changes required are significant, such as making large adjustment to incentive weights, the change will have the smallest impact on your community as possible.

Establishing the pattern that reputation can, and will, be changing over time helps set expectations with the early adopters. Getting them used to changes will make future tuning cause less of a community disruption.

End users won’t see much of the tuning to the reputation models. For example, corporate reputations (internal-only) such as Spammer-IP can be tuned and returned with impunity—actually it should be tuned regularly to compensate for improved knowledge and as abusers learn to work their way around the system.

When tuning, an A-B test where the proposed changes and the old model can be tested side by side would be ideal, but most application and metrics environments make this cost-prohibitive. Alternatively, when tuning a reputation model, keep a backup snapshot of both the model code and the values of the critical metrics of the original for comparison. If after a few days or weeks, the tuned model under-performs against the previous version, it will be less painful to return to the backup.

Application tuning

There are a number of application- and reputation-system related problems that will probably come to light only once a community of real users has been using the application for an extended duration of time. You might see hints of these misunderstandings or mis-comprehensions during early-stage user testing, but you’ll have little means of gauging their severity until you analyze the data in bulk. Forgive us an extended example, again from the world of Yahoo! Answers. But it illustrates the kind of back-and-forth tune-observe-tune rhythm that you may need to fall into to improve the performance of the reputation-related elements of your application.

Once upon a time, the Yahoo! Answers interface featured a simple, plain “Star”mechanism associated with a question. The original design intent for the star was to act as a sort of lightweight endorsement of an item, somewhat akin to Facebook’s “Like” control. Star-vote totals were to be displayed next to questions in listings, and also feed into a “Most Starred” widget (actually, a tab on a widget, displayed alongside Recent and Popular questions) at the top of the site. When viewing a particular question, you could see a listing of all other users that had “starred” that question.

As a convenience for users, there was one more feature: Answers would keep a list of all the questions that you had “starred,” and display those on your Profile for others to see (or, you could opt to keep them private, for your eyes only). It was this final feature that may have tipped the utility for some users away from seeing stars primarily as a voting mechanism and instead toward seeing them as a kind of quasi-bookmark for questions.

Up to this point, a user’s profile had only ever displayed questions that she’d asked or answered. There was no facility for saving an arbitrary question posed by anyone on the site. Stars finally gave this functionality to Answers users. One might think that this shouldn’t be a problem, right? It’s just a convenient and emergent use of the Star feature. As William Gibson said, “The street finds it own use for things.” (See more about emergence in Emergent effects and emergent defects.)

But the ancillary, downstream reputation effects of those star-votes were still being compiled, and still being applied to some very prominent listings on the site. Remember, those stars votes completely determined the placement of questions in the Most Starred listing. Over time, a disconcerting effect started to take place: users who were, in good faith, reporting bad content as abusive (see Reporting Abuse) would subsequently Star those very same questions, to save them for later review. (Probably to come back later and determine whether their complaints had been acted upon by Yahoo! moderators.)

As a result, the Most Starred tab, featured at a high and prominent level of the site, was—with alarming regularity—filling up with the absolute worst content on the site! In fact, the worst of the worst, this was the stuff that users felt strongly enough about to report it to Yahoo!. And, given the unbearable time-lags between reporting and moderation on Answers in those days, these horrible questions were actually being rewarded with higher visibility on the site for a prolonged period of time.

The Star feature had backfired entirely. When measured against the original metrics laid out for the project (to encourage easier identification of high-quality content on the site), it was evident that a redesign was called for.

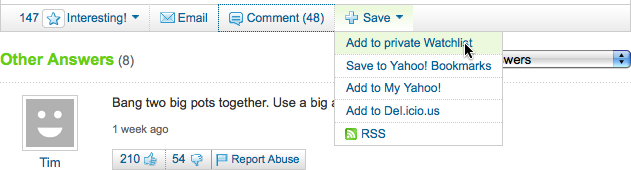

In response, the Answers team put some features in place to actually facilitate this report-then-save behavior that it was noticing, but in a way that did not have downstream reputation ramifications. The approach was two-pronged: first, they clarified the purpose and intent of the star-vote (adding the simple label “Interesting!” to the Star button was a huge improvement); second, they provided a different facility for saving a question—one intended to be personal-only, and not displayed back to the community. (And with no observable downstream reputation ramifications.) “Watchlists” on Answers now let a user mark something for future reference, but doesn’t assume any specific judgment about the quality of the question being watched (Figure 9-1).

Conditions like these are unlikely to be uncovered during early-stage design and planning, nor will their gravity be easily assessed from small-scale user testing. These are truly application tweaks that will only start to come to light under the load of a public beta. (Though they may crop up again at any time once the application is in production!) Stay nimble, keep an eye on metrics, and pay attention to how folks are actually using the features you’ve provided.

See Chapter 10 for an in-depth case study on a more comprehensive project to not only keep bad content on Answers subdued, but actually clean it up and remove it altogether, with much greater accuracy and speed.

Tuning for Behavior

There are many useful sources for reputation input, but source stands out among all others: the user. The vast majority of content on the Web is user-generated, and user feedback generates the reputation that powers the Web. Even every search engine is built on evaluations in the form of links provided not by algorithms, but by people.

In an effort to optimize all of this people-powered value, reputation systems have come to play a large part in creating incentives for user behavior: participation points, top contributor awards, etc. Users then respond to these incentives, changing their behavior, which then requires the reputation systems to be tuned to optimize newer and more sophisticated behavior (including adjustments for undesirable side effects: aka abuse). The cycle then repeats, if you’re lucky.

Emergent effects and emergent defects

It’s quite possible that—even during the beta period of your deployment—you’re noticing some strange effects starting to take hold. Perhaps content items are rising in the ranks that don’t entirely seem…deserving somehow. Or maybe you’re noticing a predominance of a certain kind of content at the expense of other types. What you’re seeing is the character of your community shaking itself out, finding its edges, and defining itself. Tread carefully before deciding how (and if) to intervene.

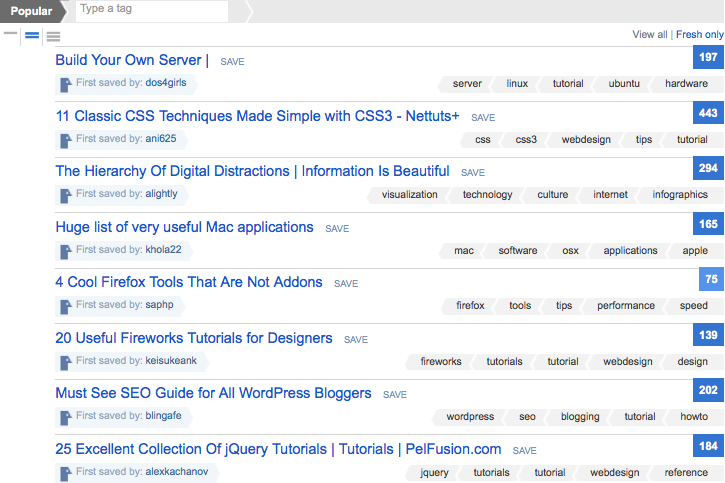

Check out Delicious’s Popular Bookmarks ranking for any given week; we bet you’ll see a whole lot of “Top N” blog articles (see Figure 9-2). Why might this be? Technology essayist Paul Graham posits that it may be the users of the service, and their motivational mindset, that explain it: “Delicious users are collectors, and a list of N things seems particularly collectible because it’s a collection itself.” (Graham explores the “List of N Things” phenomenon to some depth at http://www.paulgraham.com/nthings.html.) The preponderance of lists on Delicious is a natural offshoot of its context of use—an emergent effect—and is probably not one that you would worry about, nor try to control in any way.

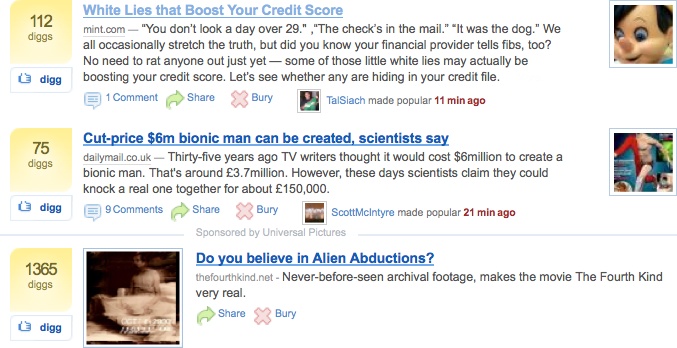

But you may also be seeing the effects of some design decisions that you’ve made, and you may want to tweak those designs now before wider deployment. Blogger and social media maven Muhammad Saleem noticed one such problem with voting on socially driven news sites such as Digg:

We are beginning to see a trend where people make assumptions about the contents of an article based on the meta-data associated with the submission rather than reading the article itself. Based on these (oft-flawed) assumptions, people then vote for or against the stories, and even comment on the stories without having read the stories themselves.

We’ve noticed a similar tendency on some community-voting sites we’ve worked on at Yahoo! and have come to consider behavior like this to be a type of emergent defect: behavior that is homegrown within the community and may even become a de facto standard for interacting, but is not necessarily valued. In fact, it’s basically a bug and a failing of your system or—more likely—user interface design.

In instances like these, you should consider tweaking your design, to encourage the proper and appropriate use of the controls you’re providing. In some ways, it’s not surprising that Digg users are voting on articles based on only surface appraisals; the application’s very design in fact encourages this (see Figure 9-3).

Of course, one should not presuppose that the Digg folks think of this behavior (if it’s even as widespread as Saleem indicates) as a defect. Again, it’s a careful balance between the actual observed behavior of users and your own predetermined goals and aspirations for the application.

It’s quite possible that Digg feels that high voting levels—even if some percentage of those votes are from uninformed users—are important enough to promote voting at higher and higher levels of the site. From a brand perspective alone, it certainly would be odd to visit Digg.com, and not see a single place to Digg something up, right?

Defending against emergent defects

It’s hard to anticipate all emergent defects until they…well…emerge. But there are certainly some good principles of design that you can follow that may defend your system against some of the most common ones:

- Encourage consumption

If your system’s reputations are intended to capture the quality of a piece of content, you should make a good-faith attempt to ensure that users are qualified to make that assessment. Some examples:

Early on in its lifetime, Apple’s iPhone App Store allowed any visitor to rate an application, whether they’d purchased it or not! You can probably see the potential for bad data to arise from this situation. A subsequent release addressed this problem, ensuring that only users who’d installed the program would have a voice. It doesn’t guarantee perfection, but a gating mechanism for rating does help dampen noise.

Digg and other social voting sites provide a toolbar that follows logged-in users out to external sites, encouraging them to actually read linked articles before clicking the toolbar-provided voting mechanism. Your application could even require an interaction like this for a vote to be counted. (More likely, you’ll simply want to weight votes more heavily when they’re cast in a guaranteed-better fashion like this.)

Think of ways to check for consumption in a media-specific way. With videos, for example, perhaps you should give more weight to opinions cast about a video only once the user has passed a certain time-threshold of viewing (or, perhaps, disable voting mechanisms altogether until that time).

- Avoid ambiguous controls

Try not to lard too much input overhead onto reputable entities, and try to keep the purpose and primary value of each clear, concise, and nonconflicting. If your design already calls for a Bookmarking or Favorites features, carefully consider whether you also need a Thumbs Up or “I Like It.”

In any event, provide some cues to users about the utility of those controls. Are they strictly for expressing an opinion? Sharing with a friend? Saving for later? The downstream effects may, in fact, be that one control does all three of these things, but sometimes it’s better to suggest clear and consistent uses for controls than let the community muddle along, inventing its own utilities and rationales for things. If a secondary or tertiary use for a control emerges, consider formalizing that function as a new feature.

Keep great reputations scarce

Many of the benefits that we’ve discussed for tracking reputation (the ability to highlight good contributions and contributors, the ability to “tag” user profiles with awards or recognition, even the simple ability to motivate contributors to excel) can be undermined if you make one simple mistake with your reputation system: being too generous with positive reputations. Particularly, if you hand out reputations at the higher end of the spectrum too widely, they will no longer be seen as valuable and rare achievements. You’ll also lose the ability to call out great content in long listings; if everything is marked as special, nothing will stand out.

It’s probably OK to wait until the tuning phase to address the question of distribution thresholds. You’ll need to make some calculations—based on available data for current use of the application—to determine how heavily or lightly to weight certain inputs into the system. A good example is the Gold/Silver/Bronze medal system that we developed at Yahoo! to reward active, quality contributors to UK Sports Message Boards.

We knew that we wanted certain inputs to factor into users’ badge-holder reputations: the number of posts posted, how well the community received the posts (i.e., how highly the posts were rated, and so on. But, at first, our guesses at the appropriate thresholds for these activities were just that—guesses.

Take, for instance, one input that was included to indicate dedication to the community: the number of posts that a user had rated. (In general, we caution against simple activity-level indicators for karma, but remember—this is but one input into the model—weighted appropriately against other quality-indicators like community response to your own postings.) We arbitrarily settled on the following minimum thresholds for badge-earners:

Bronze Badge—5 posts rated

Silver Badge—20 posts rated

Gold Badge—100 posts rated

These were simply stabs in the dark—placeholders, really—that we fully expected to tune as we got closer to deployment.

And, in fact, once we’d done an in-depth calculation of project badge numbers in the community (based on Message Board activity levels that were already evident before the addition of badges), we realized that these estimates were way too low. We would be giving out millions of Bronze badges, and, heck, still thousands of Golds. This felt way too liberal, given the goals of the project: to identify and reward only the most active and valued contributors to boards.

By the time the feature went into production, these minimum thresholds for rating others postings were made much higher (orders of magnitude higher) and, in fact, it was several months before the first message board Gold badge actually surfaced in the wild! We considered that a good thing, and perfectly in-line with the business and community metrics we’d laid out at the project’s outset.

Tuning for the Future

There are sometimes pleasant surprises when implementing reputation systems for the first time. When users begin to interact with reputation-powered applications, the very nature of the application can change significantly; it often becomes communal—control of the reputable entities shifts from the company to the people.

This shift from a content-centric to a community-centric application often leads to inspirational application designs to be built on the lessons drawn from the existing reputation system. Simply put, if reputation works well for one application, all of the other related applications will want to integrate it, yesterday!

Though new reputation models can be added only as fast as they can be developed, tested, integrated, and deployed, the application team can release new uses for existing reputations without coordination and almost instantaneously—it already has access to the reputation API calls. This suggests that the reputation team should continuously optimize for performance against its internal metrics. Expect significant growth, especially in the number of reputation queries. Even if the primary application, as originally implemented, doesn’t grow daily users by an unexpected rate, expect the application team to add new types of uses, such as more reputation-weighted searches, or to add more pages that display a reputation score.

Tuning reputation systems for ROI, behavior, and future improvements is a never-ending process. If you stop this required maintenance, the entire system will lose value as it becomes abused, slow, noncompetitive, broken, and eventually irrelevant.

Learning by Example

It’s one thing to describe and critique currently deployed reputation systems—after they’ve already been deployed. It’s another to prescribe a detailed set of steps that are recommended for new practitioners, as we have done in this book.

Talk is easy; action is difficult. But, action is easy; true understanding is difficult!

—Warrior Proverb

The lessons we presented here are the direct result of many attempts—some succeeded, some failed—at reputation system development and deployment. The book is the result of successive refinement of those lessons, especially as we refined it at Yahoo!. Chapter 10 is our proof-in-the-pudding that this methodology works in practice; it covers each step as we applied them during the development of a community moderation reputation model for Yahoo! Answers.