In all forms of research, obtaining consent from participants is the part that exposes the researcher to legal liability, which means it’s definitely something you need to pay attention to. With remote research and recruiting from the Web, there are a number of laws surrounding contacting, observing, recording, and collecting information from people online and over the telephone. Don’t let these laws intimidate you, though. We’ll address some methods to cover your bases for a typical study in the United States, provide advice for the more complex world of international research, and tell you everything you need to know to form your own rigorous approach to legal consent in remote testing.

We’ll assume that you’re using all the info collected (both from recruiting and from the research) strictly for internal behavioral user research and that you’ll remain well within reasonable ethical boundaries of information gathering for those purposes—that you’re not doing evil things like collecting Social Security numbers, selling participant info to other companies, using participant quotes and recordings in your marketing, soliciting info that might be compromising, harmful, or humiliating to the participants, subjecting the participants to unethical or uncomfortable tasks, etc. We can’t help you there. We’ll also assume that you follow the best industry practices in securing your data—keeping it off any public networks and keeping any consumer information secure and password protected.

The first few sections of this chapter cover most typical studies; the later sections deal with the daunting special cases of international studies and studies involving minors.

Last important thing: even though we discuss some legal matters in this chapter and consulted informally with legal professionals while writing this chapter, we’re no legal experts ourselves, and as such we’re not claiming to dispense legal advice in any way, shape, or form. What we’re doing is describing a general approach that we’ve been comfortable with in the past for our own specific studies. It’s impossible to generalize about legal matters for every type of study, and the only 100% foolproof way to know your personal privacy and consent issues is to talk to a lawyer specializing in Internet law. Just saying.

If you’re going to be recruiting from your Web site, you need to make sure that your Web site (or the service that’s in charge of gathering the user data for recruiting) has a privacy policy. That’s not to say that every recruit has to read through it; this information just has to be somewhere fairly easily visible and accessible on the Web site. Such policies are pretty standard, as most Web sites that allow for user registration already have them.

Your privacy policy needs to tell your Web site’s visitors a number of things. It needs to detail exactly what info is being collected from recruits, what you do with the info, and how recruits can change the info, including any related means to contact the Web site administrators. If the way in which you’re using the visitors’ information changes at all from the time you collected their information, you need to be able to contact the recruits, informing them of the update to the privacy policy. The policy should also include your organization’s legal name, physical address, contact information, a statement indicating whether you’re for-profit or nonprofit, and the name and title of an authorized representative.

If your Web site doesn’t have a privacy policy that will enable you to recruit users, we highly recommend retaining the services of an attorney to draft one for you. A competent Internet law expert can whip up a simple one in an hour. (Software and online services do allow you to create a policy yourself, but this is a one-time expense, so why risk botching it?) You can find a generic sample privacy policy at the Better Business Bureau Online (BBBOnline) Web site at www.bbbonline.org/privacy/sample_privacy.asp. There are tons of additional rules if you’re going to be collecting any information from minors under age 13, and we’ll discuss that topic in Consent for Minors, later in this chapter.

As with any study, you need explicit consent from recruits to participate, especially if you’re going to be recording the session. You’ll really need consent if any of the information or data collected from users is sensitive in any way. And you’ll super-royale-with-cheese need it if you’re testing minors or international users. A consent agreement is a contract that makes the terms of the study clear (what participants will be required to do for the study and how they’ll be observed and recorded) and then obtains explicit agreement to those terms.

Obtaining consent for a remote study is not too different from obtaining consent for an in-person study. For studies within the United States, all you’ll need is a consent agreement statement, signed with some form of tangible and unambiguous consent that can be identified with the participants. It can come in the form of a signature, an explicit verbal agreement, or a clickwrap agreement, which is a form response that users submit to signal that they’re willing to agree to the terms of the study. (You’re probably familiar with the Terms of Service/EULA agreements that come up when you’re installing software or registering for Web services; those are examples of clickwrap agreements.) Since getting someone’s signature over the phone is not very easy, you’ll probably want to use a clickwrap to get a legal record of your participant’s consent. Clickwrap agreements have been held enforceable in court a number of times in the past and should provide enough legal traction to enable you to call users to participate in remote studies.

If you’re using the live recruiting methods we explained in the preceding chapter, it just so happens that you already have a viable clickwrap form: the recruiting screener. As we mentioned in Chapter 3, always include a clear Yes/No question that asks users if you may contact them to participate in the study. Again, the question we use is this:

“May we contact you right away to conduct a 40-minute phone interview?”

In the 10 years we’ve been doing this kind of research, we’ve never run into any problems using this phrase. It’s clear, unambiguous, and provides an easy way for users to signal their intent to consent. This question should have a required response, and the form entry should not default to having the “Yes” option selected.

A clickwrap won’t necessarily suffice for any agreement you want to put into the screener. You couldn’t, for example, ask people to consent to something ridiculously unreasonable like “I agree to waive all my rights to privacy during the session” and expect a clickwrap to cover you. However, it should be fine for gathering consent to be called to participate in a remote behavioral research study.

Note

WHEN CONSENT IS INVALID

Not everyone is legally capable of agreeing to a contract. You should be particularly concerned when the person signing the contract is

A child under the age of the jurisdiction required for a contract to be enforceable. This age varies from state to state in the United States; it’s usually at least as low as the legal age of marriage. (Duh.) For user research purposes, a parent or guardian can give permission for a child to participate, although this can get really messy for children under 13 (see Consent for Minors.).

Mentally impaired.

On medication or medical care that makes it difficult to make clear, fully informed choices (interviews after surgery, or injury, or while on medications that influence thinking).

Under considerable stress, making it more difficult to make clear, fully informed choices (interviews right after a disaster, for example).

Very old, to the point at which it’s reasonable to question whether consent is completely understood.

Not fully conversant in the language of the consent agreement.

Generally, a contract signed by someone without legal capacity is null and void, as if it never existed, so that even if you have a signed contract, it’s as if consent was never actually obtained. So make sure your participants are legally capable!

Children under 13 should already be screened out (see Consent for Minors later in the chapter), and in the other cases, you should be attentive to any communication difficulties during the introductory/warm-up phase of the session. If the recruit doesn’t seem reasonably lucid or responsive, it’s best to err on the side of caution and find another participant.

For many run-of-the-mill studies, verbal consent to participate should suffice; the users’ participation as shown in the recording should make clear their willingness to participate. Of course, sometimes you’ll want more heft in your consent form, spelling out all the terms in advance and gathering more information from the users that you can use to make their consent really ironclad. This is the case for any study in which the liability risk is higher than normal or in which you expect to be exposed to more personal information than usual— e.g., studies involving medical, financial, or government-related info; info about family and other individuals; religious or political info or opinions; or any info that could reasonably be considered “intimate.”

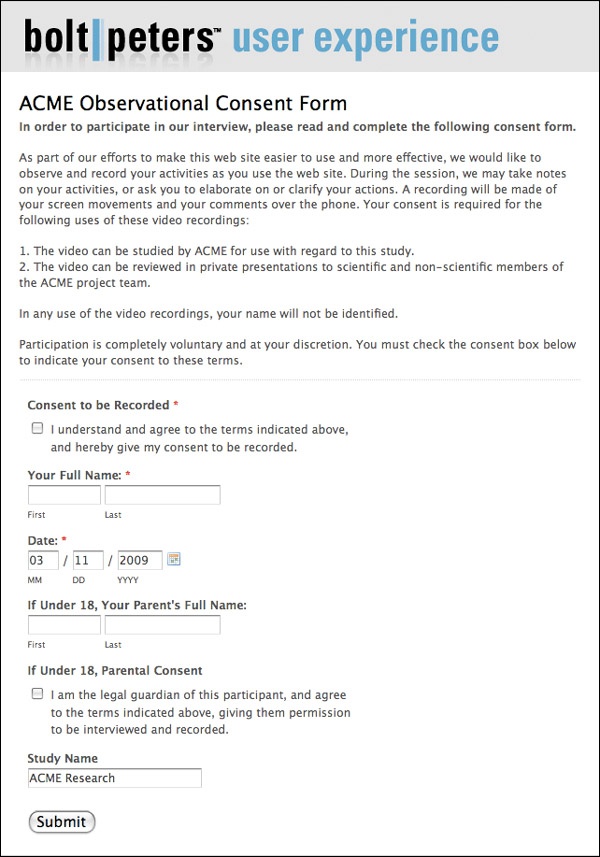

For these studies, you’ll want to make details about the study explicit to the users in a consent agreement statement (see Figure 4-1). You can include this statement in the body of your screener, either embedding it or linking to it on a separate page. Or if you want to keep the screener brief, you can also wait until you’ve contacted participants before you direct them to the full consent statement. You can simply follow the usual recruiting process to contact users, and after you’ve got them on the phone and have asked them whether they’d be willing to participate in the study, direct them to a page with a form that lays out the details of the study in plain, unambiguous terms. (See the following text for examples.)

Figure 4-1. A sample Wufoo-generated extra-strength observational consent form. You can direct the participant to this form either by sending a link or by reading the Web address aloud.

When you’re drafting your own consent statement, there are a few stylistic guidelines you can follow. Clarity is key. Short sentences and paragraphs are easier to read than long blocks of text. Organize the sentences and paragraphs to lead readers through the issues, using headings if the statement gets longer than 250 words. Use simple language. It has to be understandable at an eighth-grade reading level. Don’t use words like “aforesaid,” “said” (as in “said recordings”), “hereinafter referred to as,” “hereunder,” “thereunder,” “witnesseth,” or “for good and valuable consideration, receipt of which is hereby acknowledged.” Those words are all confusing and vague; plus, they make you look pretentious and lame.

In the United States, there are federal and state laws regarding the legality of recording telephone conversations.

Note

ONE-PARTY AND TWO-PARTY STATES

In the United States, there is a federal law that states that in a telephone conversation between two or more parties, at least one of the parties must consent to be recorded in order to legally record the conversation.

Beyond that, there are individual state laws as well. States can be either “one-party” or “two-party” states. One-party states require the consent of only one of the parties in the conversation to be recorded, whereas two-party states require the consent of everybody who’s in the conversation. When you call across state lines, if either side of the conversation is in a two-party state, you need to abide by the laws of the two-party state. The two-party states are Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Washington. In Michigan, anyone who’s participating in the conversation can record the conversation, but any outside party listening in on the conversation needs to get the consent of all participating parties. All other states are one-party states.

For more info on telephone recording, consent, and wiretapping, check out the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press Web site at www.rcfp.org/taping.

If you’re recording the session in any way, you should get explicit consent for all the different recordings you’re doing. We’re not aware of any laws specifically regarding the recording of other people’s computer screens and webcam feeds, but it’s just good common sense to get at least the same level of explicit consent that you’re getting for the telephone recordings.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) describes three ways to get permission to record a telephone conversation:

You get verbal or written consent to record from all parties before the conversation begins;

or

You give the participant verbal notification about the recording, which is recorded at the beginning as part of the call, by whoever is recording (i.e., you);

or

You play a “beep tone” sound at regular intervals over the course of the conversation, indicating that the session is being recorded.

For the sake of thoroughness, we recommend both of the first two options, asking for permission to record both before and immediately after the recording has begun. We like to start the recording by saying

“Okay, so now the recording has begun, and I’m able to see your screen. Can I reconfirm with you that you agree to participate in this remote research study, and that you understand that both the conversation and your computer desktop will be recorded for research purposes, until the end of the session? The recording won’t be used for anything other than our own research, and we won’t share it with anyone else.”

Once you’ve jumped through these hoops, you’re free to begin testing.

Note

CONSENT HELPS BUILD TRUST

All this fuss about consent isn’t just to cover your own ham hocks; it’s also there to give your participants some peace of mind about your trustworthiness. At this point in time, most people aren’t used to being called right away after filling out forms on the Internet, so when you get consent from users, you’re also helping to assure them that you’re not going to take over their computers, abuse their information, or do anything else underhanded.

At any rate, you’ll still be amazed that most users are totally willing to participate in these kinds of studies without hesitation. Since they’ve already filled out the screener that prepares them to be contacted, it’s not as if you’re cold-calling them. We’ve found they’re usually pleasantly surprised at being contacted.

Testing internationally is trickier for two main reasons: language differences can make it harder to gather informed consent, and consent laws vary for every single country. Covering every single case for every single country for every set of research goals wouldn’t just take a whole book; it would fill a whole law library. In the following sections, we’ll touch on general approaches for getting participants in other countries, pointing out the considerations where it’s important to have due diligence in your consent gathering.

The first thing we’ll acknowledge about international consent is that it can be easier to obtain consent by recruiting through other methods than do-it-yourself live recruiting. The simplest option is to hire a recruiting agency or research facility to find the participants. There are international services that do this kind of recruiting, and also companies native to the country you’re testing in. We’ve gone through Apogee Group Recruitment to find users all the way over in Hong Kong, Acorn Marketing and Research Consultants in Singapore, and Cooper-Symons Associates in Australia. (You can probably find what you’re looking for by googling “research participant recruiting agency [city/country name].”)

Many research services will also assume the responsibility for obtaining participation consent and arranging incentives so that you don’t have to deal with international money transfers yourself. That’s a big plus.

Another way to approach recruiting is to contact a qualified lawyer in your testing region, preferably one who specializes in privacy and consent law, to draft an international consent form in the native language, tailored to the goals of your study, which you can place online for recruits to fill out. We’re told that drafting a consent form for a typical UX study would require a few hours of work.

Here are some bits of info you should be prepared to discuss with the lawyer:

Your research objectives.

What kinds of information will be collected (especially recordings and personal info).

How the information will be used, applied, and stored.

Who will have access to the information.

Who will be contacted to participate, and how they will be contacted.

What participants will be expected to do during the research session.

How participants will be compensated.

How participants will be able to contact you with any questions afterward.

It never hurts to reach out to other research practitioners in the country you’re testing in to ask them what they think the major consent and privacy issues of the region are, or whether they know of any useful resources or legal experts to refer to if you want to learn more. UX practitioners can be found working as consultants, working for large companies, or on professional networks like LinkedIn. Don’t be shy about contacting market researchers and academic researchers too, since they encounter many of the same issues. As always, use due diligence to determine whether the practitioners are reputable.

Note also that, though local practitioners may know plenty about testing within their country, they may not be aware of the issues surrounding testing between countries (and there are usually plenty). So this is more of an extra step than a complete strategy for learning everything you need to know.

[Note: We’ve adapted most of this info about Safe Harbor laws into lay-speak from the Department of Commerce’s Web site, at http://export.gov/safeharbor.]

If you plan on striking out on your own, here’s an example of the kinds of rules and regulations you can expect to learn about. The U.S. Department of Commerce maintains a set of principles called “Safe Harbor,” dictating the privacy standards all U.S. organizations must comply with when dealing with people in the European Union. You need to adhere to the seven Safe Harbor principles and then certify your adherence.

The seven principles are summarized as follows:

Notice. You need to let your recruits know about the purposes for which you’re collecting and using their information, providing them with information about how they can contact you with inquiries or complaints, any third parties to which you’ll be disclosing the information, and all the choices and means you’ll be offering the recruits for limiting the use and disclosure of their info.

Choice. Recruits must be given the opportunity to “opt out” of having their information disclosed to a third party or used in some manner other than the one for which it was originally collected or subsequently authorized by these individuals (i.e., screening and contacting the recruits for the study). When sensitive information is involved, you need the users’ explicit “opt-in” consent if you’re going to disclose their info to a third party or use it for something other than screening or contacting for the study.

Onward Transfer. To disclose information to a third party, first you have to apply the Notice and Choice principles. You can transfer information to a third party only if you make sure that the third party subscribes to the Safe Harbor principles or is subject to the Directive or another adequacy finding. Another option is to enter into a written agreement with the third party, requiring that it provide at least the same level of privacy protection for the recruits’ information as the Safe Harbor principles require.

Access. All recruits have to be able to access the personal information you’ve gathered about them and then be able to correct, amend, or delete that information where it’s inaccurate, unless the burden or expense of providing this access would be disproportionate to the risks to these individuals’ privacy or where the rights of persons other than the recruits would be violated.

Security. You have to take “reasonable” precautions to protect personal information from loss, misuse and unauthorized access, disclosure, alteration, and destruction.

Data Integrity. The personal information you collect has to be relevant for the purposes for which it is to be used, which in the case of recruiting means that all the screener questions need to relate to your study goals. You should take “reasonable” steps to ensure that the data you collect is reliable for its intended use and also that it is accurate, complete, and current.

Enforcement. You’ll need to have three things to make the Safe Harbor principles enforceable. First, you need readily available and affordable mechanisms that allow individuals to file complaints and have damages awarded. Second, you need procedures for verifying that the commitments companies make to adhere to the Safe Harbor principles have been implemented. Finally, you need to have a plan to remedy problems arising out of any failure to comply with the principles. The sanctions must be rigorous enough to ensure your compliance. You need to provide annual self-certification letters to the Department of Commerce to be covered by Safe Harbor.

To certify your adherence to the Safe Harbor principles, you can either join a self-regulatory privacy program that adheres to the Safe Harbor requirements (BBB OnLine, TRUSTe, AICPA WebTrust, etc.), or you can self-certify. To self-certify, you’ll have to submit a four-page Safe Harbor application form (which can be found on the Web site) to the Department of Commerce, along with a $200 registration fee. As long as you want to be covered by Safe Harbor, you’ll also need to recertify every year, which costs $100.

And that’s just the basics. Kinda complicated, huh? But that’s the kind of stuff you’ll have to brush up on if you’re going to brave the waters of international testing for the first time, all by yourself. Nobody said it’d be easy. Once again, complete details about Safe Harbor can be found at http://export.gov/safeharbor.

Note

WHAT’S MY LIABILITY?

Failure to disclose the terms of your information gathering and usage in sufficient detail may expose you to claims of fraud, deception, invasion of privacy, and intentional infliction of emotional distress.

Breaking privacy or consent laws can subject you to really breathtaking fines from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), Department of Commerce, or other government agencies. On top of that, if you’re using the information or consent for illegal purposes (spying on users, selling off personal info, etc.), you can get fined far worse than that.

For broadcasting without informing the people being recorded, the FCC can fine you up to $27,500 for a single offense and no more than $300,000 for continuing violations.

And violating COPPA (see the following section), probably the touchiest of all these legal concerns, can cost tens of thousands of dollars in the minor cases, and up to $1 million in the most serious case yet (Xanga in 2006).

Please stick to the law.

At last, we’ve reached the infamous liability snake pit: minors. In the United States, there’s a law called the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 (COPPA), which lays out the requirements for Web sites that collect personal information from children. So first, the good news: COPPA covers only children under 13 years of age, so testing teenagers (age 13–17) isn’t much different than usual. Still, we urge you to take precautions with teenagers, less for the sake of liability and more because you don’t want parents to get anxious about their children talking to strangers on the phone. Make an extra-strength clickwrap agreement for both the participant and the participant’s parent to fill out. The participant’s parent should consent to having his/her child participate in a 30–40 minute research study, with the understanding that the child will be observed by the moderator with screen sharing software. You should also encourage the parent to observe the session if he/she wishes.

So, then, what to do about minors under 13? Our legal guy said this: “Every single time I’ve had a client who was starting a Web site and wanted to contact children under the age of 13, 100% of the time I have convinced them not to do it. From an administrative standpoint, it’s really, really painful.” There you have it, gentle readers. Hiring a recruiting agency to deal with contacting minors can lift the tremendous burden of contacting, recruiting, screening, and gathering informed consent from minors and their parents.

But, okay, what if you wanted to do your own recruiting, for whatever reason? We’ll tell you one thing: you probably won’t be able to do “live recruiting” in the sense that you can intercept the user in the middle of a natural task. Gathering the proper consent will most likely take a considerable amount of interruption, since it involves getting a lot of heavy-duty parental identification and consent. Recruiting over the Web with a screener, however, is still an option; you’ll just have to switch up your approach. A clickwrap isn’t gonna cut it here, and neither is an email from the parents’ email address telling you that they consent. To comply with COPPA, you need rock-solid “verifiable parental consent” (see the sidebar). You shouldn’t even bother targeting the minors directly. Instead, your screener should target parents who may be willing to allow their children to participate in a remote study, or else it should direct any minors who might see the form to get their parents to fill it out for them.

In short, recruiting minors under 13 is a colossal migraine, a lot of work, and incredibly liability prone (fines begin in the tens of thousands and go up past the million dollar mark). If you don’t have the budget for a recruiting agency, you’re bound to follow COPPA rules. See the FTC’s “How to Comply with The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule” (www.ftc.gov/bcp/edu/pubs/business/idtheft/bus45.shtm).

Most generic privacy policies state that the Web site doesn’t collect information from minors under 13. If you are collecting such information, though, you have to make a bunch of amendments to your privacy policy. The complete set of rules, “Drafting a COPPA Compliant Privacy Policy,” is at www.ftc.gov/coppa. The gist of it is that your Web site has to do six things:

Link prominently to a privacy policy on the homepage of the Web site and from wherever personal information is collected.

Explain the site’s information collection practices to parents and get verifiable parental consent before collecting personal information from children (with a few exceptions).

Give parents the choice to consent to the collection and use of a child’s personal information for internal use by the Web site and then allow them to opt out of having the information disclosed to third parties.

Provide parents with access to their child’s information and the opportunity to delete the information and opt out of the future collection or use of the information.

Not make a child’s participation in the study require disclosing more personal information than is reasonably necessary for the activity.

Maintain the confidentiality, security, and integrity of the personal information collected from children.

As before, we strongly recommend getting a legal expert to either draft such a policy or to look over your draft to make sure everything checks out.

Not even verifiable parental consent will necessarily allow you to record minors. In some states there have been cases in which the parents’ consent for the minors to be recorded on behalf of the minors—“vicarious consent”—hasn’t held up in court (like Williams v. Williams in Michigan, 1998), so you just don’t want to risk it. We advise capturing your sessions the old-fashioned way: take really good notes.

For a remote study, you need to obtain various forms of consent for contacting recruits, getting people to participate, and recording the session. There are important additional requirements for international users and minors.

In order to collect any data from Web site visitors, your site needs to have a Privacy Policy.

You can obtain participation consent for a typical domestic nonminor user study by using an online Consent Agreement clickwrap form. Make sure the user can give valid consent and that you’re not collecting sensitive information.

We recommend obtaining consent to record the session by confirming verbal consent both before and after the recording has begun.

Learning the ins and outs of international consent is simpler if you consult recruiting agencies, lawyers, and user researchers who work in the region you’re testing in.

When testing minors aged 13–17, obtain an extra-strength clickwrap consent from both the participants and their legal guardians. Testing minors under 13 is tremendously inconvenient and requires verifiable parental consent and compliance to COPPA laws. Don’t record minors.