Tackling the General Ledger

In This Chapter

![]()

- Why the general ledger matters

- Understanding general ledger transactions

- Working with misplaced transactions

- Recording noncash and nonposting transactions

- When you shouldn’t change your general ledger

The essence of your accounting records, or your books, is a report known as the general ledger. This comprehensive report records every transaction that affects your accounting records.

As you’ll see in this chapter, most but not all transactions you enter into your accounting software are recorded in the general ledger. Your accounting software takes care of most of the work for you as you prepare invoices for customers, issue paychecks to employees, and pay bills to vendors. However, you’ll need to use a special transaction type known as a general journal entry to record certain activities that affect your books or to correct misposted entries.

The Importance of the General Ledger

At first, your general ledger might feel a bit overwhelming, because depending on the number of transactions you have in a given month, the report can easily run dozens or even hundreds of pages. The report is always arranged in the order of your chart of accounts, which we discussed in Chapter 4, and includes all of your accounts that have activity. You might not see accounts that have a 0 balance or haven’t ever had any transactions posted to them; this varies by accounting software.

Each account reflects the following information:

- Account number (if you choose to use account numbers within your software)

- Account name

- Beginning account balance

- Transaction type, such as invoice, bill, payment, check, journal entry, and so on

- Customer, vendor, or employee name, when applicable

- Transaction date

- Descriptive information, such as a memo or item description (Your accounting software might automatically provide this when you enter the transaction, or you can add it manually.)

- Some accounting programs include a column that shows you the other side of a given transaction; -SPLIT- in this column signifies that the transaction affected three or more general ledger accounts instead of just two (The desktop and online versions of QuickBooks show this, but not all programs do.)

- Debit and credit columns (remember: debit = left, credit = right)

- Ending account balance

RED FLAG

Some accounting programs go to great lengths to simplify accounting procedures and reports—sometimes too far. For example, Xero’s General Ledger report doesn’t include any transaction activity and is actually what most accountants would call a trial balance report, which we discuss in Chapter 17. If the general ledger in your software doesn’t provide as much detail as we describe here, look for an alternative, such as the Account Transactions report in Xero.

This general ledger report from the desktop version of QuickBooks is pretty typical of what you’ll see in other programs.

Typically, your accounting software lets you see the detail of any general ledger entry when you click or double-click it. For example, if the amount you see in the ledger originated with a check you wrote, you can click on the amount and the actual check will open. The transaction activity will identify a customer, vendor, or employee, if applicable, along with any descriptive text you entered when you recorded the transaction.

In QuickBooks desktop, double-clicking the check issued to Gregg O. Schneider in the preceding figure shows the actual transaction where the check was written.

By having both the general ledger entry and the full transaction detail, you have two different means to make corrections to misposted transactions.

Updating Transactions Directly

Let’s say you find a mistake in your books where a transaction is in the wrong account. In many cases, you can simply click or double-click the transaction amount to display the original document window and make your corrections.

Be careful when changing dollar amounts of transactions if you’ve already reconciled the bank or credit card account for that period. Modifying a cleared transaction can throw your previous reconciliation out of balance, which will carry forward to your current reconciliations. (We discuss reconciliations in detail in Chapter 8.)

However, you’re not stuck if you encounter a transaction you can’t fix directly, thanks to general journal entries.

Adjusting Journal Entries

You can use an adjusting journal entry to correct account balances in your books. This is a standard operating procedure.

Such transactions are typically dated as of the last day of a month, but you can use any date in the month if necessary. At the very least, you or your accountant will make journal entries at the end of the year to properly close the books (as discussed in Chapter 17). Typical year-end journal entry adjustments include recording depreciation (addressed later in this chapter and in Chapter 17). Your accounting software automatically generates a hidden journal entry that zeroes out your income statement.

BOTTOM LINE

At the end of each fiscal year, all your revenue, cost of goods sold, and expense accounts reset to 0. It might be disconcerting to see beginning balances for your assets, liabilities, and equity at the start of the new year but not the other types of accounts. This is to be expected, as your income statement starts over at 0 at the beginning of a new year, while your balance sheet accounts carry their balances forward perpetually.

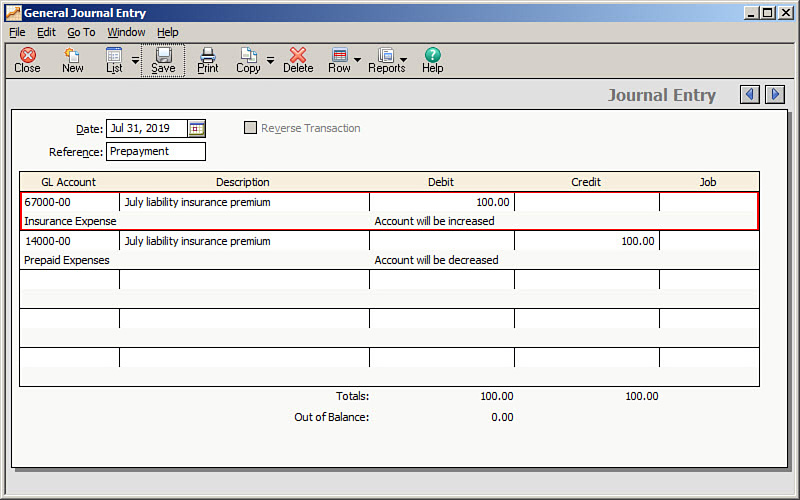

In addition to year-end journal entries, there may be times when an adjusting journal entry is required to correct an error or affect a necessary change. For example, if you paid for insurance expense for the year and recorded a prepared asset (debit) of $1,200 reflecting the entire insurance payment, then each month you’re going to make a journal entry to reduce (credit) the prepaid asset by $100 and expense (debit) that month’s share of the insurance cost.

This Sage 50 transaction moves $100 from Prepaid Expenses to Insurance Expense for the month of July.

ACCOUNTING HACK

If you have more than one bank account, you might sometimes need to record a transfer of funds between the accounts. Some accounting programs have a Transfer command that allows you to easily record the movement of funds. However, in any accounting software, you can always use a journal entry to post the transfer. You’ll debit the cash account receiving the funds and credit the account the funds come out of. Take the time to document the reason for the transfer within the journal entry so you can remember later when reconciling your bank account or reviewing your general ledger.

You might discover that transactions were entered incorrectly into your books. Maybe inventory items were set up incorrectly, which can in turn affect how revenue, cost of goods sold, or inventory amounts are recorded in your books. As covered in Chapter 5, when selling physical goods, you must specify general ledger accounts that indicate where to post the sale of an item, the item cost for the item, and your inventory account on your balance sheet. It’s all too easy to inadvertently choose the wrong accounts when setting up an item.

Let’s say you use the same general ledger account for both the Cost of Goods Sold and Inventory account fields. As you sell items, your accounting software posts a debit and a credit to the very same account, resulting in a 0 impact in your books. Normally when you sell items, cost of goods sold should increase and inventory should decrease. Some cloud-based programs, such as QuickBooks Online and Xero, prevent you from making such a mistake, but many desktop programs don’t have such built-in protections.

As shown in Sage 50, the Cost of Goods Sold Account for this item should not be Inventory but rather an expense account.

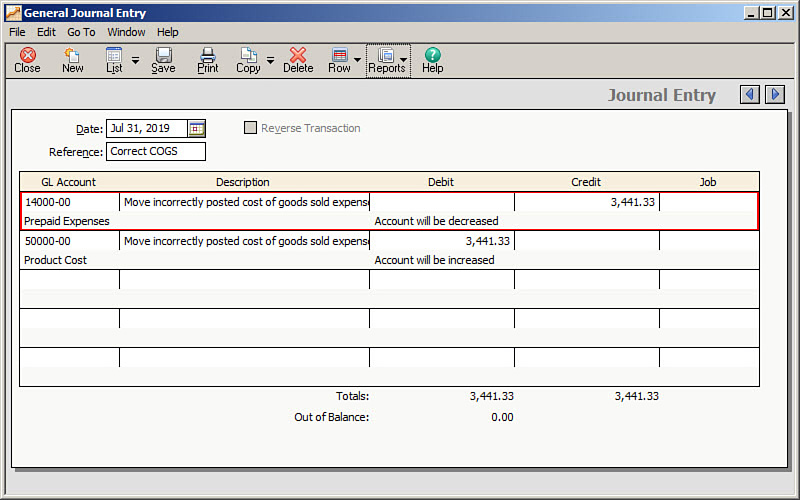

Maybe dozens or even hundreds of invoices were posted incorrectly in this fashion. Because your accounting software automatically posts inventory-related transactions in the background, correcting such mistakes isn’t as easy as you might hope. Fortunately, accounting rules allow you to correct mistakes. To do so, you’ll record a journal entry in your books to adjust the account balances in question to their actual amounts, as shown in the following figure.

This adjusting entry in Sage 50 moves activity double-posted to Inventory to the Cost of Goods Sold account, which corrects both accounts.

Remember, the sum of the debits for every journal entry you record must match the sum of the credits. We’ve seen numerous accounting software users attempt to create what’s referred to as a one-sided journal entry, in which they want to force one account to be a certain amount without affecting any other accounts. You can’t do this in your accounting software. When you touch one account with a journal entry, you have to ensure you also touch at least one other account for balance.

As you can see, there’s a lot to accounting and entering transactions. You don’t want to allow just anyone to enter journal entries—only knowledgeable users well versed in accounting should do so. Likewise, you shouldn’t allow your employees to simply double-click and change the original entry because the traceability (sometimes called the audit trail) is gone forever. The proper use of a journal entry documents why the transaction is being changed. If you’re ever unsure about a journal entry, consult an accountant or your tax adviser.

Your accounting software gives you several ways to determine if any journal entries have been added, and in some cases by whom:

General Journal Entry transaction window: Your accounting software might provide an on-screen list of recent journal entries when you go to add a new entry. This can help you avoid inadvertently recording the same entry twice.

QuickBooks desktop always gives you an easy glance at previous journal entries.

General Journal report: This report, if available in your accounting software, is simply a list of all journal entries recorded in your books during a specific timeframe. In cloud-based programs such as QuickBooks Online and Xero this is considered an advanced report.

In QuickBooks desktop, you can filter the Journal report to show only journal transactions.

Audit Trail report: Most accounting programs offer a report that records the date, time, username, and details of all new and changed transactions in your books. This can be helpful when you need to figure out why a certain entry is in your books or who put it there.

Xero’s equivalent of an Audit Trail report is called History and Notes.

Sometimes you might find mistakes in your books that were made last year or even earlier. For example, maybe you incorrectly posted an amount to an expense account that actually belongs in a balance sheet account. In such cases, you can’t post the correction directly to the expense account, because doing so distorts your current year financial statements. Also, the change should have affected prior year books, so correcting entries in prior years that affect revenue, cost of goods sold, or expense accounts must use your Retained Earnings account as the offset instead.

A typical example of a prior period adjustment is a journal entry to correct an error in depreciation. Suppose you miscalculated the depreciation on a new piece of equipment—you should have taken an extra $500 in depreciation expense—but your books for the year are already closed (as discussed in Chapter 17).

A journal entry to depreciation expense is inappropriate at this point because the error is on last year’s expense, not this year’s, and last year’s income and expenses have already been zeroed out and combined with your retained earnings account on your balance sheet. You need to make a prior period adjustment.

Instead of debiting depreciation expense for the $500, you’ll debit retained earnings. The offsetting credit goes to accumulated depreciation because that account isn’t closed out at the end of the year.

Note that you’ll also have to make this change on your tax return for last year. If you’ve already filed the return, you might need to amend it to make the correction. At least make a note in your tax file so there’s a record of the additional deduction.

Finding Misplaced Transactions

Your eyes might glaze over when looking at your full general ledger. That’s understandable. To gain more insight from the general ledger, including finding misplaced transactions, consider modifying the report options within your general ledger to only view selected accounts. This can help sharpen your focus.

Or export the report to a spreadsheet, such as Microsoft Excel. In Chapter 22, we discuss using the Filter feature to collapse a report based on specified criteria.

You also could print the report and make notes with a pen and highlighter. You might use a significant amount of paper, but the change of venue from your screen to a printed page can help make issues in your general ledger easier to spot.

Another option is using the transaction search feature in your accounting software. Desktop-based programs often have a Find command on the Edit menu. Cloud-based programs may have a magnifying glass icon you can click to display a search window.

Finally, some accounting programs, such as the desktop version of QuickBooks, offer centralized screens for customers, vendors, employees, and inventory. These allow you to quickly scan through transactions posted for a specific customer or a particular amount.

Noncash Transactions

Your accounting software provides easy-to-use transaction screens for any activity that records money going into or out of your business. However, there are certain transactions you only can post in the form of journal entries.

For example, IRS Publication 946 explains in great detail how to depreciate property. The journal entry itself is simple enough: you’ll debit a Depreciation Expense account and credit an Accumulated Depreciation account. What isn’t necessarily simple is determining the amount of depreciation to record.

Many small businesses outsource depreciation calculations to their accountant or tax adviser, but some programs, such as Xero, have a built-in feature for calculating depreciation and posting the amounts to your books. Other programs get you part of the way there. QuickBooks, for example, allows you to create a list of fixed assets, but you must use either the Accountant or Enterprise version to calculate depreciation and automatically record the corresponding journal entries.

Alternatively, income tax programs like TurboTax, TaxAct, or H&R Block may allow you to perform the calculations, but you’ll most likely have to enter the transactions in your books manually. This can lead to a circular situation in which you can’t complete your tax return until you calculate depreciation in the tax software, post the entries in your books, and update your financial results in the tax software again.

Many small business owners question the need to depreciate assets because doing so doesn’t have any effect on the operation of the business. Unfortunately, some amount of paper shuffling is endemic to accounting. The aforementioned Publication 946 has 114 pages of guidance on depreciation alone. What’s more, your business might need to maintain two sets of depreciation schedules—one for book purposes and a second for tax purposes. Accounting rules require you to record depreciation for your books, but there can be tax advantages involved in maintaining a second set of depreciation schedules.

The U.S. Tax Code spans thousands of pages, so clearly we can’t get very deep into many tax aspects in this book. With that said, a knowledgeable tax adviser likely can save you much more than you pay him or her in fees on your income tax bill—and provide the peace of mind of knowing your books are compliant with both IRS and general accounting rules.

In some cases, you can record depreciation for an asset all in one year, often referred to as Section 179 depreciation. Under certain circumstances, the IRS enables you to take a current year tax deduction for the entire purchase price of equipment and software you use in your business instead of spreading the cost over several years. As of this writing, most small businesses can deduct up to $25,000 of equipment and software that’s placed in service by the end of the year. But exceptions abound, so consult your tax adviser for current Section 179 limits. Journal entries to record Section 179 depreciation debit Depreciation Expense for up to the permissible limit and credit Accumulated Depreciation by the same amount.

Nonposting Transactions

You may have heard an accountant or bookkeeper state they “posted a transaction to the books.” This simply means they recorded the transaction in the accounting software. However, there are three types of transactions you won’t ever see posted in your general ledger: estimates or quotes, sales orders, and purchase orders. Each of these is a placeholder transaction that eventually leads to activity on your books.

As mentioned in Chapter 6, you might prepare an estimate for a customer who’s considering your products or services. No money changes hands as the result of this request for pricing, so you won’t see the estimate listed in your general ledger. When the customer approves the estimate, your accounting software likely allows you to convert the estimate to either an invoice or a sales order.

Invoices appear immediately in your general ledger, but sales orders are simply a request for you to deliver products or services. Again, no money has changed hands yet. Once you fulfill all or part of the sales order, you’ll create an invoice that will then appear on your books.

Purchase orders work in the same fashion, except in this case, you’ve placed a request with a vendor for products or services that haven’t yet been fulfilled.

Your accounting software enables you run a report that shows open estimates, sales orders, and purchase orders. You can use these reports to stay abreast of pending transactions awaiting action.

When Not to Use Journal Entries

You might be thinking journal entries are the magic cure for anything that ails your books. Journal entries do make it easy to make corrections on your books, but you can compromise your books by using journal entries in the wrong situations.

Here are a few instances when you shouldn’t use journal entries:

In Chapter 13, we show you the correct way to write off invoices that customers cannot or will not pay. Instead of journal entries, you use credit memos to offset these invoices so your Accounts Receivable balance always matches your balance sheet account.

Similarly, we show how to use vendor credit memos in Chapter 13 to write off bills from vendors that you’ve either entered twice or purposefully won’t be paying. Using a journal entry to force your Accounts Payable balance down can result in your balance sheet not reconciling with your Aged Payables report.

You periodically might need to write off inventory that’s spoiled, been damaged, or gotten lost. We referred to this as shrinkage in Chapter 5, where we also showed you the proper method for adjusting your inventory balance. Be sure to use the inventory adjustment feature offered in your software; journal entries cannot record changes in quantity on hand in your inventory records.

If you use your accounting software to process payroll, as we discuss in Chapter 9, always use payroll transactions to record adjustments to an employee’s paycheck. Your accounting software only takes actual payroll transactions into account when you generate payroll tax returns and reports, as we discuss in Chapter 18. Adjustments that you make by way of journal entries can result in misstatements on your payroll tax returns.

The Least You Need to Know

- The general ledger houses every single financial transaction that occurs in your business.

- Adjusting journal entries are used to enter certain noncash transactions and correct errors in the general ledger.

- Prior period adjustments are used to correct errors and make changes that affect accounting years that have already been closed.

- Your accounting software offers multiple ways for you to find misplaced transactions.

- Certain transactions such as sales orders, purchase orders, and estimates never post to the general ledger.

- You should not use journal entries for transactions such as invoice and inventory write-offs; however, journal entries are the only way to post noncash entries such as depreciation and amortization.