The Big Three Financial Statements

In This Chapter

![]()

- A look at your P&L, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows

- Reviewing the big three to check your business health

- Correcting errors

As noted in Chapter 1, accounting can be thought of as a means of keeping score within your business. Therefore, financial reports can be thought of as the scorecards for different periods of time.

The financial reports discussed in this chapter—the P&L (or income statement), balance sheet, and statement of cash flows—consolidate transaction information from a variety of accounts in your accounting software. Most programs are already set up to generate these reports automatically, but you generally can customize them to suit your specific needs.

Because these reports gather key metrics that indicate the relative strength of your business, you might be asked to share them with lenders or investors when seeking a loan or capital investment, for example.

This chapter helps you learn about the key aspects of each report and how you can use the reports to interpret the health and status of your business.

The Profit and Loss, or Income, Statement

Although most financial reports are referred to by a single name, an income statement has several monikers. You might have heard the terms P&L, profit and loss, profit and loss statement, or just income statement. These are all names for the same report.

In essence, an income statement is a summary of revenues and expenses for a specific time period. Businesses usually run the P&L for both the current month and the calendar year to date.

A special characteristic of the income statement is that it’s reset to 0 at the start of each new fiscal year. However, this doesn’t mean your business’ income and expenses simply vanish. Your accounting software automatically moves the prior year’s income and expense activity into the Retained Earnings account on your balance sheet.

DEFINITION

The Retained Earnings account on your balance sheet reflects the accumulated net income your business has generated from inception to date, less any dividends or distributions that have been paid out to owners or shareholders. The Retained Earnings account is a required element in every set of books.

Included on the P&L are various types of accounts that reflect the money from all sources your business is earning from and offsetting expenses to—the places where your business is spending money. Sample income accounts might include Sales and Service Revenue. Sample expense accounts might include Salaries and Wages, Supplies, Rent, Utilities, Advertising, Depreciation, and Employee Benefits.

It’s important to note that when you start using a software program to track your business’s financial activity, there will likely be a list of accounts (called a chart of accounts, which we discussed in Chapter 4) available. You can add any account names appropriate for your business to that list. So for a pet boarding business, you’d add an account for Pet Food. You also can remove account names that don’t apply to your business.

The P&L is also a place where you reflect income that belongs to your business but actually isn’t part of your business purpose. Typically, income or expense in this category is placed at the very bottom of the P&L statement to highlight that it’s not part of income from the normal business operations. For example, if you have your extra money in an interest-bearing bank account or mutual fund, the interest or dividend earnings on that money appear on your P&L. Also, if you sell assets that belong to the business, like a company car, the profit or loss on that sale appears on the P&L.

Ideally, your income statement always reflects net income (more income than expenses) at the bottom, but you might sometimes reflect a loss when you have more expenses than income in a given period. The term P&L or profit and loss actually is a misnomer, because this report won’t typically reflect both a profit and a loss. A better name would be the profit or loss report, reflecting that your business either made a profit or incurred a loss.

The income statement typically reflects the activity for your business through the end of a fiscal year—which for most businesses, is a calendar year. At the start of each new fiscal year, say January 1, the income statement starts over at 0 and begins accumulating new information again.

The fiscal year is the year you use for tracking your business financial activity. As noted, for most companies, this is a calendar year. Some companies, however, can choose a year that’s more appropriate to the ebb and flow of their business activity. The federal government, for example, uses September 30 as the last day of its fiscal year, so the financial statements for the government cover the period from October 1 through September 30 instead of a calendar year.

Your income statement is a scorecard for a period of time that shows revenue you’ve generated and expenses you’ve incurred.

ACCOUNTING HACK

Many accounting software programs enable you to expand and collapse various levels and categories of information in generated reports to just what you want to see. Expanding or collapsing information does not affect the calculated subtotals and totals in the reports.

By nature, accountants tend to be pragmatic, so the balance sheet is aptly named. Simply put, it’s a listing of account balances at the end of a given time period. Balance sheets are broken down into three major sections:

Assets: This section contains the book balances of accounts of what your business owns or is owed.

Liabilities: This section contains the balances of what your business owes to others.

Equity: This section reflects what would be distributed to stakeholders of your business should you close the business and liquidate your assets. The amount of equity is the difference between your assets and your liabilities.

Your balance sheet reflects what you own and owe. The difference between those two amounts is the net worth of the business, or the equity.

The historical nature of accounting reports means that the amounts you see in the assets section do not necessarily reflect the current reality. A building listed at a $500,000 book balance on the books might be worth a multiple of that amount, or a fraction, today. If a balance sheet reflects equity of $1,000,000, that doesn’t necessarily mean you can close up shop and pocket a million dollars.

In short, accounting records do not reflect current fair market value for assets. They only reflect fair market value at the point that an asset purchase is first recorded. After that, the value of the asset might rise or fall, but these fluctuations aren’t recorded in the accounting records until the asset is sold. The true value of your business equity can be determined only by appraising all the assets you own and then subtracting any liabilities presently due.

DEFINITION

The book balance of an asset on the balance sheet may differ from its fair market value. For instance, if your business owns a building, the book balance on your balance sheet is whatever you paid for the building less accumulated depreciation. The fair market value of an asset is the amount an unrelated third-party would willingly pay to purchase that asset.

The major headings within the balance sheet—Assets, Liabilities, and Equity—are further broken down into subcategories so you can get a better sense of what the business owns. Let’s look at a handful of typical balance sheet subcategories next.

Current Assets

This section reflects assets your business owns that can be converted to cash either immediately or fairly readily. Examples include bank balances, accounts receivable, inventory, employee loans, security deposits, and prepaid expenses.

Anything on your balance sheet that’s either cash or can be readily converted to cash is considered a current asset.

Long-Term Assets

This section reflects assets your business owns or is owed but that might take some time to convert to cash, including investments, real estate holdings, equipment, notes receivable, and construction in progress.

This section reflects amounts you’ll need to pay in the short term, typically within 1 year. You also might see these referred to as short-term liabilities. They include accounts payable and long-term debt that must be paid back within the current fiscal year.

Current or short-term liabilities represent money your business will be required to pay to others in the near future.

RED FLAG

When reviewing a balance sheet, ideally the Total Current Assets value should exceed the Total Current Liabilities line. Current assets represent the short-term liquidity of a business, meaning the ability to handily cover any bills that will come due in the near future. If current liabilities are close to or exceed current assets, it’s very likely that a cash crunch is imminent for your business.

Long-Term Liabilities

This section reflects amounts your business owes but won’t have to pay back until some point in the future. Subcategories here include things like mortgages and car loans.

This section reflects the net earnings or loss from inception to date, along with investments made into the company, less distributions made to owners. In other words, these types of equity items represent the book value owned by the owners of the business, which would be a starting point for valuing the business in the event the business was sold. Examples include capital contributions, common stock, and retained earnings.

Equity represents the book value of the business, a starting point for valuing the business as a whole.

DEFINITION

Within financial statements, book value is a theoretical figure that shows what the owners would get if the company was liquidated as of the financial statement date. We say theoretical, because items on the balance sheet could be sold for more or less than their book value. This differs from fair market value.

The Statement of Cash Flows

Accounting reports are all interrelated, in that no one report stands on its own. As we’ve seen, the net income or loss from an income statement rolls into the Retained Earnings section of your balance sheet. Although your income statement reflects the revenue and expenses for given periods, it doesn’t necessarily reflect the actual cash in and cash out for your business.

For example, when you make a loan payment, only a portion of that amount may affect your income statement. For a loan payment of $1,000, $200 might be interest and $800 would be principal. The $200 in interest appears on your income statement as an expense but the $800 principal amount does not appear there. Instead, this amount reduces a short-term liability on your balance sheet.

The statement of cash flows reflects cash in and cash out for a business.

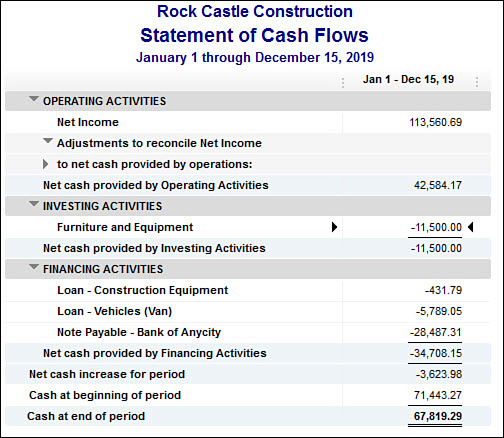

Thus, the statement of cash flows helps you follow the money. The report starts out with your ending cash balance as of the previous accounting period, typically the prior month. It then has three sections: cash flow from operations, cash flow from investing activities, and cash flow from financing activities.

Cash Flow from Operations

The cash flow from operations (Operating Activities in the preceding figure) is the actual net cash in or out of your business. This isn’t necessarily equivalent to the Net Income line amount at the bottom of your income statement. Indeed, net income in your income statement may reflect invoices customers haven’t paid yet, bills from vendors you haven’t paid yet, noncash accounting adjustments such as depreciation and amortization (see Chapter 7 and the later “Depreciation on Fixed Assets” section for more about depreciation), and the current month’s portion of a prepaid expense.

From an accounting perspective, income and cash flow are two very different measurements.

Cash Flow from Investing Activities

Cash flow from investing activities (the Investing Activities section in preceding figure) includes money related to ownership stakes in your business, such as contributions you make to get the business started or to fund ongoing operations or distributions you make to yourself and other owners to share profits from the business.

Cash Flow from Financing Activities

Cash flow from financing (called Financing Activities in the preceding figure) reflects cash in or out of your business related to money you’ve borrowed to help fund the business. This section includes both new money you’ve borrowed as well as monies you’ve paid back, such as money borrowed on or repaid for a credit card, activity related to a working capital line of credit, funds borrowed on or repaid to car loans and mortgages, and money you or a related party loan to the business temporarily.

Reviewing Your Financial Statements

Each report derived from your accounting software gives you insight into your business from a different perspective.

For example, the balance sheet shows what you own, what you owe, and what the book net value (as opposed to the fair market value) of your business is. Reviewing the balance sheet is helpful to understand where things stand, but another purpose for reviewing financial statements is to catch accounting errors. In this section, we review some common issues you might find when reviewing your financial statements.

We assume you’re going to be using accounting software. Further, we assume you’ll be viewing your financial reports on-screen. Your accounting software certainly allows you to print reports on paper, but the primary benefit to viewing reports on-screen is that corrections are just a click or two away. Most accounting programs allow you to drill down into an underlying transaction so you can view the source of that information. If you find that you’ve put all or part of a transaction in the wrong spot in your books, you can fix it easily.

RED FLAG

Be sure to review your financial reports regularly and in a timely fashion. Corrections you make within a month or so of the end of the accounting period have little to no ramifications. Finding errors down the road means you could end up paying more or less income tax than you should, so the impact can be magnified. Indeed, depending on the magnitude of the correction, it’s possible you could have to file an amended income tax return, which could lead to unintended and unwanted regulatory scrutiny. Corrections are always easiest if you haven’t yet filed your income tax return.

Reviewing Your Income Statement

Your income statement starts over again at 0 at the start of each fiscal year, so the effect of any errors you make on the income statement are limited to affecting a single accounting year. However, it’s still important to perform a review to ensure that your records are in order.

First, you’ll want to be able to compare your financial results from one month to the next, as well as one year to the next. Over time, this can help you identify trends and determine which of the products and services you offer are doing well and which are starting to lag.

Second, the amount of federal and state income tax you pay each year is predicated by your income statement. Errors on this report can result in over- or underpaying your income taxes. Overpaying is simply a monetary penalty, but underpaying due to poor accounting can result in criminal prosecution.

With that background in mind, let’s look at some typical income statement issues.

If you have multiple income accounts, you’ll want to ensure that items are categorized properly in each account. For example, if your business offers both consulting and training services, you’ll likely have a Consulting Income account as well as one or more Training Income accounts. Ensuring that amounts are classified correctly gives you the ability to monitor trends based on each of these lines of service.

Also, when reviewing expenses, be on the lookout for accounts that don’t show any expense when they should. For instance, let’s say your company’s monthly health insurance premium is paid by credit card. If you forget to reconcile your credit card statement in a given month, you might not have a health insurance premium amount. This can give you the false impression that your net income is higher than it truly is. Plus, you potentially miss out on a valuable income tax deduction if you don’t record every expense for your business in a timely fashion.

RED FLAG

Some accounting programs let you enter transactions without specifying an account on each line. The intent is to simplify data entry, but this convenience comes with potential problems. Transactions entered this way get lumped into either Uncategorized Income or Uncategorized Expense on your income statement, and as a result, you can’t meaningfully compare revenue and expenses by type from one period to the next. Also, say you write a check for a security deposit. This is an asset to you—money you’ll get back at some point in the future. However, if it’s lumped into Uncategorized Expenses, you won’t carry the asset on your books and will claim an invalid income tax deduction on it.

Now, let’s move on to the balance sheet and look at some typical corrections you might need to make. Unlike the income statement, your balance sheet never gets zeroed out until you liquidate your business, so any errors here could potentially linger for years.

Cash account: The cash balance on your balance sheet should always be reconciled with your bank statement. (Chapter 8 covers reconciliation.) No matter how closely you think you’re watching your cash, it’s easy to miss transactions. Here are some common occurrences:

- You record a payment or deposit twice.

- You forget to record an automatic withdrawal from your account, such as bank fees or an automatic payment.

- You neglected to record an ATM transaction.

- If you’re fortunate enough to have customers who pay invoices by Automated Clearing House (ACH), you might not notice when a payment posts to your bank account so you didn’t record it in your books.

- You handwrite a check, and when posting it into your accounting software, you enter it into the wrong bank account.

Fortunately, you’ll catch all these issues when you reconcile your bank account, so cash account errors on your balance sheet usually take care of themselves.

Accounts Receivable: Accounts Receivable represents the amount your customers owe you. The amount in your Accounts Receivable account on your balance sheet should always match the bottom line total on your Aged Accounts Receivable report. Typically, your accounting software takes care of this for you. However, your Accounts Receivable account can get out of balance.

For example, when recording customer invoices in your accounting software, you might post a line item detail transaction to the Accounts Receivable account. In other words, the invoice amount automatically increases your Accounts Receivable account in your software, but when you enter the description of what this income is for, it’s easy to forget and post the offsetting amount to Accounts Receivable as well. This results in a debit and a credit to the same account, which in effect fails to record the revenue and results in a 0 amount transaction on your books, even though the invoice itself reflects an amount due.

Also, be especially careful when recording journal entries that affect your Accounts Receivable account. Only in rare instances should you need to force activity into your Accounts Receivable account with a journal entry. This account should only be affected by posting invoices, credit memos, and customer payments. If your Aged Receivables Report doesn’t match your Accounts Receivable account on your balance sheet, something’s gone awry in your books.

One way to track down an error is to review the detail of the Accounts Receivable account in your general ledger and look at the Type (or Transaction Type) column. The exact transaction type codes might vary based on your accounting software, but valid transactions in the Accounts Receivable account typically appear as one of these items:

- Invoice (sometimes abbreviated IN)

- Credit memo (sometimes abbreviated CM)

- Customer payment (sometimes abbreviated PMT)

- Check (sometimes abbreviated CK; any checks that post to this account should solely be to issue a refund to a customer)

RED FLAG

Transactions that have a type of general journal or that look anything like general journal entry should be scrutinized closely, as journal entries cannot affect the Aged Accounts Receivable report. Your general ledger report typically includes a Transaction Type column, and general journal entries typically are indicated by the abbreviation GJ or the word Journal. This differs from accounts receivable related indicators like INV (Invoice), CHK (Check), PMT (Payment), or RCPT (Receipt).

The Type column for your Accounts Receivable account within your general ledger helps you identify misposted transactions.

Inventory: Another account you should never affect by way of a general journal entry is your Inventory account. Your ending inventory balance on your balance sheet should always match the inventory valuation report your accounting software provides. Always use transaction forms in your accounting software to record the purchase, sale, and write off of inventory.

Discrepancies in inventory balances can be tracked down in the same fashion as misposted accounts receivable transactions. If you use a journal entry to try to make a correction to your inventory account balance, the other inventory management reports your software provides will no longer tie back to the ending inventory balance on your balance sheet.

Now, let’s go back to our pet boarding business example. It’s the end of the year, and you find that you still have some pet food on the shelves that’s expired, or perhaps a bag tore and the food spoiled. Your accounting software has a means you can use to record an inventory adjustment, which removes the unsalable food from your books and record an expense. In this case, what was an asset—the bag of pet food—has become an expense.

Always ensure that you use inventory adjustments and not journal entries to make corrections to inventory balances.

Prepaid Expenses: Most accounting programs don’t offer a means of reconciling prepaid expenses, so you might want to use a spreadsheet to maintain supporting schedules. Examples of prepaid expenses include insurance premiums you pay in advance, such as for a vehicle.

DEFINITION

Your Aged Accounts Receivables report is an example of a supporting schedule, which provides additional detail a standard accounting report isn’t suited to display.

Let’s say you get a discount for paying $1,200 for a full year of insurance in advance. You wouldn’t post the entire $1,200 in a single month, as this is really 12 monthly expenses of $100 each. Instead, when you pay the initial bill for your vehicle insurance, you’ll post the transaction to a Prepaid Expenses account. Then, each month by way of a journal entry, you’ll debit Insurance for $100 and credit Prepaid Expenses for $100. At the end of 12 months, the Prepaid Expenses account should have a balance of 0.

Typically, you can use a single Prepaid Expenses account to temporarily store all your prepaid expenses in one spot. However, because the prepaid expenses will likely be amortizing over different time periods, you might want to maintain a spreadsheet where you can log and reconcile the ins and outs of the prepaid expenses account. We provide an example of such a schedule in Chapter 22.

Fixed Assets: Economists like to use the term durable goods to describe appliances and equipment consumers purchase. Fixed assets are much like durable goods for your business.

It’s important to properly account for these items, which usually have a longer life within your business and a greater expense than day-to-day purchases like office supplies. The federal or state tax codes that apply to your business might require that you not record the expense for these items all at once, but rather over a period of years. Further, your local government might assess a personal property tax, sometimes referred to as an ad valorem tax, on such items.

When reviewing your fixed assets, be sure equipment such as office furniture, laptops, cash registers, machinery, and so on have been categorized properly on your balance sheet. Otherwise, your operating expenses may be improperly distorted.

Depreciation on Fixed Assets: The theory behind depreciation is that the cost of major expenditures relates to a period of time longer than the current year. If you purchase a piece of equipment, say for $3,000, there’s an assumption that you’re going to use the equipment to generate income for several years. So you should expense the cost of the equipment over those same years to present a fair picture of your income, offset by appropriate expenses.

We use depreciation expense to represent the wearing down or the usage of fixed assets over a period of time. Ideally, that period of time relates exactly to how long the asset is expected to last, but in reality, some assets last seemingly forever, like a building or a file cabinet.

The IRS has taken the guesswork out of determining the life of an asset by preparing tables that tell you how much to depreciate and over how many years the depreciation should occur. You can view online or request a printed copy of IRS Publication 946: How to Depreciate Property. It gives you the life expectancies and depreciation options for all your fixed assets.

BOTTOM LINE

Depreciation is a complicated area and one most small business owners turn over to their accountant because there are many different ways items can be depreciated and choices to make. Typically your accountant calculates the depreciation for you and gives you a journal entry to make monthly or once a year.

Other Assets: This catch-all category reflects assets that don’t fit into the other categories on your balance sheet, such as security deposits that have been refunded.

When a landlord or utility company refunds a security deposit, be sure to zero out the amount that appears on your balance sheet. If you record the deposit on your income statement as revenue, you’ll inadvertently pay income tax a second time on money you’ve already paid income tax on once.

Current Liabilities: When reviewing your balance sheet, be sure to reconcile the Accounts Payable account in the same way we described for Accounts Receivable. In some cases, you might enter a bill to be paid later but then in haste write a check you post as an expense without applying it to the unpaid bill. If you’ve paid the bill separately but the liability remains, this can result in double-counting one or more expenses. Such transactions distort your net income and could result in an improper income tax deduction.

As with Accounts Receivable, you should never try to make an adjustment to your Accounts Payable account with a general journal entry. Doing so puts your balance sheet out of step with the supporting schedule.

Other issues that can arise in the current liabilities section of the balance sheet report are mismatched payroll tax liabilities. Your accounting software is designed to handle most of the payroll tax tracking for you, but if you work outside the built-in forms, you can end up with discrepancies.

Similarly, if you remit a payroll tax amount but use the Payroll Tax Expense account for your check instead of a liability account like Federal Withholding, you’ll end up with a double-counted expense as well as a fictitious liability on your books.

Long-Term Liabilities: Many small businesses won’t have long-term liabilities if they’ve used short-term financing options such as credit cards or contributed capital. However, if you do have some sort of long-term financing, when reviewing your balance sheet, be sure to compare the balance of any long-term debt with the associated amortization schedule for the loan.

DEFINITION

An amortization schedule shows how each loan payment you make is allocated between principal and interest. Principal reduces the remaining balance of the loan; interest is an expense for holding someone else’s money. We show how you can create an amortization schedule on your own in Chapter 22.

Equity: You shouldn’t have to make entries in this section very often. However, one thing to be on the lookout for is your retained earnings amount dropping below 0. This can signify that your business is consistently losing money, or that the ownership of a profitable business is making excessive distributions.

Typically, a business should only distribute any net income that remains after all expenses are recorded, although in certain circumstances, you might temporarily overdistribute to meet external cash requirements or fulfill previous commitments.

If you review your financial reports on a monthly basis, you’ll typically catch issues immediately and can fix them in the same accounting period. In other cases, it could be months or years before you realize a mistake was made in a prior accounting period. The actions you take will be driven by the amount of the error as well as the type of account:

Income statement accounts: If the incorrectly reported activity is in your current fiscal year, simply fix the transaction. If the activity is in a previous fiscal year, you’ll need to decide whether it’s material enough to fix. If you determine that the activity is material, a journal entry is necessary to make the correction.

DEFINITION

Materiality means is the amount significant enough to have a meaningful impact on the financial statements. The concept of materiality varies from one business to another.

Balance sheet accounts: These accounts never get zeroed out until you close down and liquidate your company, so mistakes you leave in place on your balance sheet can haunt you into the foreseeable future. The balance sheet is intended to be a clear picture of what your business owns, is owed, and has earned over the years. Always make corrections to the balance sheet so you have a clear picture of your financial standing.

The Least You Need to Know

- Financial reports interrelate to each other, and your accounting software consolidates information from various accounts to create them.

- The profit and loss, or income, statement is a summary of revenues and expenses for a specific time period.

- The balance sheet is a listing of account balances at the end of a time period and is intended to be a picture of what your business owns, is owed, and has earned.

- The statement of cash flows reflects cash in and cash out for a business.

- Review your financial statements to find and correct any underlying errors, both for accuracy and to avoid any resulting concerns such as tax liabilities.