CHAPTER 4

Trust and the Crisis of Institutional Legitimacy

There are moments when you meet someone and your perspective on life changes forever. For me, that person was Jin Naibing, then the vice mayor for culture, health, and education for the city of Kunshan, in southeastern China near Shanghai. From the instant that we were introduced in 2007, Jin demonstrated an outsized understanding of global disruption—its causes, its dangers, its likely repercussions—that was astounding for someone who had never lived outside China and who had an unabashed loyalty to her relatively small city. Indeed, her particular foresight about why global institutions are failing everywhere and her clear analysis of why people distrust institutions perfectly presaged the contours of the ADAPT framework I would soon develop. Jin’s analysis gave me a much more penetrating platform with which to study institutions and how they can be made to serve us better. She bemoans her own dour conclusions about institutions because, like me, Jin believes in their value (particularly the importance of great universities) in tethering towns, regions, and nations while elevating their prospects.

Now in her late fifties, she came of age in the latter stages of Mao Zedong’s reign, when the Gang of Four and the Cultural Revolution were in full swing—closing universities, burning books, banishing people from the cities to work in the fields, and promoting reeducation campaigns. Although Jin hasn’t spoken to me about that period, the social and political positions she has staked out for her community are the antithesis of the Cultural Revolution’s tenets.

Jin’s family was relatively poor when Jin was growing up. The small town of Kunshan relied on agriculture and products fired in primitive kilns for its marginal economy. But by 2003, when Jin was named Kunshan’s vice mayor, the city’s limited manufacturing base had been transformed into an electronics factory hub with at its peak more than four thousand, mostly Taiwanese, companies (including Foxconn, which makes Apple products). Kunshan’s population had swelled, chiefly with the addition of migrants who poured into the city from rural areas in central China to work in these plants.

Jin saw the bustling economic activity in Kunshan as a golden opportunity to improve the town in crucial ways that would put it on the path toward becoming a world-class city. She believed Kunshan would be making a mistake if it assumed that its manufacturing activity would be enough to ensure a thriving future; global economic conditions change, she thought, and a city that isn’t continuously taking advantage of its good fortune to make marked improvements in its residents’ quality of life and social and economic prospects is in effect going backward, no matter how many factories dotted its downtown. This was not a common position for local public officials in China, either then or now; officials tend to be more conservative in their approach to enhancing local conditions, or they may use a post to advance their progress through the system, most often to another city. But Jin is unique and she has an uncommonly deep devotion to Kunshan, which grows out of a profound belief that an abiding loyalty to one’s community and its people is an obligation, not merely an option.

Four of Jin’s initiatives from the early 2000s are noteworthy. First, she created an education system and better housing stock for migrant workers, improving their conditions so they were on par with Kunshan’s native population. Jin felt it was wrong to do otherwise. Second, she dedicated the upper story of the well-respected art museum in Kunshan to works and performances produced by the city’s children, including migrants, and put on competitions to raise the profile of Kunshan’s cultural output throughout the region. This effort to teach and encourage creativity among Kunshan’s kids was designed to make up for the failings of China’s education system and its misguided emphasis, as Jin saw it, on rote learning. It would be almost another decade before the rest of the country began to adopt new teaching strategies that more closely reflected Jin’s policies in Kunshan. Third, she upgraded the quality of local healthcare facilities by seeking out private hospitals from around the world. Fourth, her most ambitious project, Jin attracted an elite American university to Kunshan.

That’s what brought me to Kunshan. In 2007, just before becoming a dean at Duke University, I toured China seeking a location to establish a campus of the Fuqua School of Business. A Canadian consultant hired by Jin to help her find a university for Kunshan learned about my trip and encouraged me to meet with her. Jin’s response to my introductory remarks reshaped my thinking in a profound way. In describing the reasons why she felt Kunshan needed a respected American university, Jin insightfully and deftly foreshadowed today’s crisis of institutional legitimacy, which had only begun to sprout at the time.

Jin’s prescient analysis of a university’s value to Kunshan validated the continuing importance of institutions in the world, while simultaneously exposing the global shortcomings that lead individuals to increasingly distrust institutions and view them as irrelevant at best and malevolent at worst. Years before my conversations with people in myriad regions about their deepest worries, Jin had the uncanny sagacity to begin to sketch out the categories of the ADAPT framework—the pronounced concerns that people everywhere had—which would grow out of those exchanges. Jin’s argument was so compelling and fresh that I came bearing an American business school for her city and she ended up getting an entire first-class university, dubbed Duke Kunshan.

The crux of Jin’s argument about institutional failure grew out of her farsightedness concerning four troubling developments:

- The negative consequences of disruption. Technological disruption would soon have a devastating effect on Kunshan and other midtier cities in developing nations. The economic success of Kunshan and its ilk was based on a low-cost, high-skilled labor model that was about to become less desirable as artificial intelligence and robotics took jobs away from local workers. (Indeed, in 2016, Foxconn cut its Kunshan workforce in half from 110,000 to 50,000, due to the introduction of robots and as many as six hundred major Kunshan companies say they have similar plans). Jin was rightfully worried that the new wave of technology would concentrate in larger cities with major universities, access to capital, and a technology-savvy employee pool, cities like Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Beijing. Not only would technological disruption destroy the economic pillars of places like Kunshan, it would also turn their residents into second-class citizens, with all of their towns’ growth and progress over the recent decades overlooked and their prospects slipping.

From an institutional perspective, Jin knew that the existing institutions in Kunshan, established to support a large, human-intensive industrial model, would require a complete overhaul for the city to maintain its prominence against other, more dominant urban areas in China, particularly as disruption changes the social and economic landscape. Kunshan would need a comprehensive strategy to install new infrastructure; attract more technologically-savvy talent, venture capitalists, and entrepreneurs who would start up new businesses and industries; retool and upgrade the existing population’s skills; and build a truly smart city. To do this, Jin concluded, and not become another forgotten locale, Kunshan needed a world-class, twenty-first-century university to build around.

- The negative consequences of global fracturing. Jin and I were both admirers of Samuel P. Huntington’s book The Clash of Civilizations, in which the author argues that in the post–Cold War era, deeply embedded cultural (and in some cases religious) identity would determine the seats of conflict in the world.1 In this telling, China and the United States would, among other regions, vie for economic and political power based on very different cultural views of political, social, and civic structure. The risk was that this fracturing would lead to a very unstable world fraught with risks without the international institutions to manage it. As the world fractures in this way, Jin believed that institutions that could cross borders would be desperately needed to allow debate, seek agreement, and understand the comparative strengths and weaknesses among countries. She hoped that Duke, with its history of encouraging and protecting open dialogue, would fulfill that role in China, allowing for collegial and candid conversations where otherwise they were necessarily inhibited. At the same time, Jin anticipated that American students attending the university would get a more balanced and accurate picture of Chinese life, customs, beliefs, and politics than if they attended a school in the United States. In short, Jin’s goal was to develop generations of young people who had a deep appreciation for the differences between the world’s major societies and a respect for those distinctions.

- The negative consequences of demography. Jin’s third thought was targeted more at why Duke would want to set up shop in Kunshan, rather than at the reason Kunshan needed Duke. She pointed out that demography was going to put great pressure on education systems around the world. In the United States, Europe, Canada, and Australia, populations were aging and the number of domestic students applying to universities in these countries was declining. Hence, universities in these countries had become dependent on foreign student enrollment to pay the bills. Jin believed that this strategy would ultimately fail. As education systems improve in other countries and as nationalism takes hold, there would be fewer foreign students available to these schools. Opening a campus in China, one of the world’s most populous countries and an attractive destination for students from around the globe, would help mitigate impending student shortages for a large university, Jin said. She was actually making a much larger point about the impact of demography on all of our rickety institutions. Education systems have too few or too many people. Taxes increasingly depend upon diminishing population pools to provide revenue for basic services and social systems. Public job development programs and the private sector are unable to keep up with demand for good-paying positions in places where the number of young people is exploding.

- Institutional inertia. Perhaps most important, as a close observer of institutions, Jin recognized that the Chinese education system as currently structured would resist the types of change needed for China to compete in a world being transformed by new technological advances. The existing system still had many elements of the Soviet educational approach it was modeled on, in which universities were generally expected to graduate students who could be put to work at state-owned enterprises, in heavy manufacturing, or at some government leaders’ pet projects. In general, these activities were heavily influenced by the past—not by a future that will bear very little similarity to previous generations.

For China’s educational system to respond effectively to the forces of global disruption, Jin foresaw that it would have to change radically both in terms of what was taught and researched and how it was taught and researched. It would have to be well-suited to training students for careers in private entrepreneurship, technology, and service businesses, with a focus on rapidly evolving areas of specialty such as healthcare, analytics, the environment, and new forms of biology and material science. Jin hoped to bring Duke in as a catalyst for Chinese universities, compelling them by example to adapt and provide Chinese students with the knowledge and tools they would need to navigate and innovate in a world of new dynamic technologies. Fortunately for Jin, the Chinese deputy minister of education responsible for the regulation of foreign universities agreed with her on the need for such an outside stimulus. Duke’s agreement with China includes a variety of governance rules to ensure that the university’s academic standards and freedoms are no different in China than in the United States. Duke was meant to be an exception that informed the whole.

Jin’s insights about institutions and detrimental global trends are all the more remarkable when you consider that they came before the economic crash would worsen the fissures in the world, before the rise of neopopulist movements, before the rapid growth in disparity that marked the past ten years, before the unraveling of a consensus focused on initiatives designed to serve the global good, before the emergence of US–China tensions, before trade wars, and before the aging of China’s and America’s populations highlighted the threats of demographics. By pointing to the way institutions, such as a university, can serve a valuable public good that goes well beyond merely offering a degree, Jin was also challenging institutions to be dynamic and responsive to changing trends and conditions—to safeguard traditional civic norms and to be sufficiently malleable to reshape their own roles for the better as norms shift.

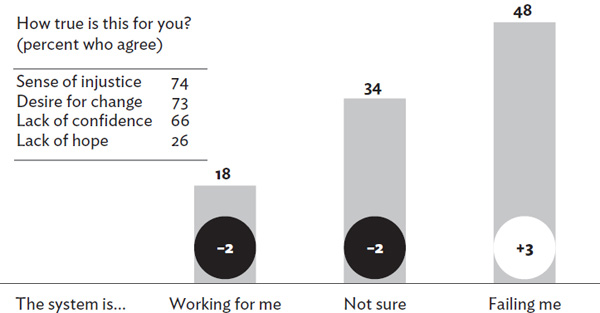

Unfortunately, Jin’s worst fears about global institutional sclerosis have been borne out. In different ways all institutions that are designed to make our societies work are in crisis—the international order, most political systems, health systems, financial systems, legal and policing systems, tax systems, and the fourth estate. The most direct evidence of this crisis was captured by the 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer (Figure 4.1). In this survey, which measured attitudes toward institutions and social and political systems in twenty-six countries, less than one person in five said that the system is working for them and nearly three-quarters of respondents expressed a sense of injustice about the world they live in and a desire for change.

Institutions are struggling to navigate a contradiction. Typically, being slow to adapt is a plus for institutions central to the effective functioning of society. Without a stable police force, for example, we do not have security. Without a stable financial system, organizations, products, and services cannot get formulated and built, and business cannot be conducted. Without a stable tax system, governments do not have the money to run themselves. Without a stable education system, the population cannot learn, grow, and adapt. Traditionally, we trust and rely on institutions because they in fact provide stability.

FIGURE 4.1 Percentage of population who feel that the system is working for them. SOURCE: 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer.

But in a time of severe technological disruption, economic uncertainty, cynical political disinformation campaigns, racial and social fracturing, questions being raised about whether schools are providing the type of education that students need and mounting worries among so many people that the system as a whole is leaving them behind, institutions must be more agile and adapt to help minimize the harm that these and other trends can inflict. How long can political discourse be infected by false information on social media before democracy and fair elections are permanently undermined? Can police forces defy calls for more transparency when communities, rightly or wrongly, believe they are under siege from the police themselves, their presumed protectors?

The challenge for institutions is for them to be able to change rapidly without inciting insecurity in the society they are designed to serve and without damaging the essential oversight that makes them stable forces in the world. If institutions change too fast, or in the wrong way, they risk disenfranchising the people they are designed to serve. However, if they change too slowly, they risk irrelevance. To examine this difficult balancing act more closely—and, really, the inability of institutions to manage it well—it is useful to more closely analyze how institutional failure in an age of disruption is playing out through the lens of essential institutions in our societies.

Technological Disruption: The Erosion of the Fourth Estate

Without real intervention, existing critical institutions are either maladaptive to a technology-based world or undermined by it. Consider the plight of the media, which we touched on in chapter 1. Complaints about the accuracy of the press have always been with us, but at least since colonial times and the rise in influence of institutionalists like Edmund Burke it was generally accepted that the press’s essential role in society was to help ensure an informed citizenry.2 Without an informed populace, democracy cannot thrive, because under that system people have to make decisions about the future of their countries—and without accurate information, they cannot make good choices. The problem is, many people don’t believe any more that the media is an honest broker. For instance, according to a Pew Foundation survey in the United States, 46 percent more Democrats than Republicans believe that the press acts in the interest of the public. Even more alarming, only 16 percent of Republicans highly engaged in the news trust what the press produces, compared with 91 percent of Democrats.3

In other words, the press today is seen as serving the public good by only half of the population—and politically a very specific half. Similar results emerge from surveys in Europe with trust in press at the lowest point among people who consider themselves middle class and residents of southern European countries that are not performing as well as their northern counterparts. Finally, throughout the world people who do not support their current governments are more likely to feel that the media is not covering political issues fairly.

With these survey results, it should come as little surprise that twelve of the top fifteen polarizing brands in the United States are media companies, according to Morning Consult.4 Trump Hotels, Smith and Wesson, and Nike are the sole nonmedia organizations on that list. I suspect everyone can predict the two media firms that are most polarizing: CNN and Fox News. Living in the United States and being unable to avoid seeing what is on these two stations from time to time, it is easy to conclude that some parts of the media are indeed extremely tilted. I have had dozens of conversations with people who have expressed concerns that competing views of politics are causing conflict in their families, among spouses, parents, children, and siblings. When I ask them where they get their news and information, it is clear that they are starting from completely different bases of fact—invariably one watches Fox News and the other CNN. I usually suggest they find a more neutral source they can agree on as a starting point for their discussions. Most cannot find one.5 It is naïve to believe that media was ever really “neutral” in the absolute sense of the word, but journalistic balance in reporting and lack of bias in presenting a story seem to be disappearing at an alarming rate.

The combination of three interwoven elements best explain press polarization. First is the general loosening of regulations that require media to be balanced in its coverage. Second, there are so many more news options across the political spectrum to choose from as lower barriers to entry create dozens of new information channels on the Web, TV, radio, and podcasts. Third are commercial opportunities. In the scramble among new and existing news organizations for profitability, the winners are media organizations that can attract a large audience cohort from the vast disintermediated group of eyeballs and ears seeking information. In that environment, finding and maintaining a large following is difficult without a compelling and hard-to-resist sales pitch. As it turns out, the most irresistible option for people are echo chambers that confirm their political beliefs rather than oblige them to question their version of the truth.

Global Fracturing: The Decay of Multilateral Institutions

Budding national insularity—countries digging in to defend social, cultural, and political differences rather than endeavoring to forge compromise across differences—splinters the world into dozens of separate, unyielding parts. This causes a more profound issue: fracturing is depriving us of the cooperative global institutions we need to address problems at an international level. This splintering is undoubtedly under way now. For instance, meetings such as the G7 and G20 once played a valuable part in providing nations with informal means to help steer through challenging issues across the globe. This was on full display in 2007–2008, when the G20 finance ministers used the goodwill and consensus of their group to right the global financial system after the market crash. Lately, however, G-level meetings have become less effective as countries and leaders pursue their own self-interest over seeking a collective global agenda, be it on climate change, trade, or any other pressing issue.6 In many ways the G-summits have abetted the rise of populism, nationalism, and political polarization and have been decreasingly successful because of that.

But the G20 is not the only significant multilateral institution that is on the ropes today. In 2016, South Africa withdrew from the International Criminal Court, a twenty-year-old organization formed to prosecute international transgressions, including genocide and war crimes. Burundi, The Gambia, and Russia soon followed. The World Trade Organization has been unable to agree on its latest liberalization of global trades rules, known as the Doha Development Agenda, an effort that has been under way for two decades. And perhaps the most prominent illustration: in 2019 in the UK, the Conservative Party won a decisive victory in the General Election on a clear anti-EU platform that ended three years of uncertainty and accelerated the government’s plan to take the UK out of the EU. These are just a few examples, as the list is indeed very long.

Since multilateral institutions are voluntary, there are two primary requirements for them to be successful: all parties must abide by their decisions and they should appear to perform the functions they were designed for.7 Neither of those requirements hold very often anymore. Only two countries are abiding by the Paris Climate Accord; there were two more vetoes in the UN Security Council in the past five years than in the entire decade from 1990 to 2000 and were only two less than there were between 2000 to 2010. A host of countries are completely ignoring the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty.

Polarization makes sustaining multilateral institutions increasingly difficult, as national leaders are focused on the particular interests of their own country to the exclusion of broader global interests. What is most disturbing is that there are still issues at a global scale that require engaged coordinated action, such as climate change, management of infectious diseases, nuclear proliferation, military conflicts, and elements of trade and job growth. Without effective multilateral organizations, these issues will not be resolved.

Demographic Dilemma: The Shortcomings of Education

Demographic trends are seriously impacting educational systems. In more economically developed countries, where population growth has slowed, there is less revenue available to improve educational opportunities, in part because tax receipts and the number of applicants are in decline. And in generally less well-heeled countries, where the cohort of young people as a percentage of the population is skyrocketing, the need for stellar educational programs starting from elementary school could not be more urgent, but the financial wherewithal and the ability to develop these programs are lacking.

In truth, educational systems as indispensable institutions have failed us for quite some time; the consequences are just more perilous today. For instance, most of the best precollege private schools and universities are off-limits to less wealthy people unless the student can fight through the chain of obstacles that stand in the way of good scholarships. This advantage for richer families continues in the graduate school realm: the universities providing the greatest opportunities after graduation disproportionately admit wealthy students. All of this produces a vicious cycle in which wealth provides access to better education and improves education outcomes.8 This often leads to more wealth and more educational opportunities for the next generation of the top 1 percent families.

To interrupt this cycle, sufficient funding of public education at the elementary to high school and university levels is required. That, however, is nearly impossible today. Part of the problem is another flagging institution: tax systems. The current forms and levels of taxation are leading to sharp reductions in the overall amount of money available for critical social needs like education. In most countries today, tax policies tend to favor the rich, deriving proportionately less money from the top 1 percent than the rest of the population. This is in sharp contrast to tax-paying ratios of the mid-twentieth century and is worsening along with income disparity.

Equally problematic, sales or value-added tax (VAT) are a larger burden for those on the lower rungs of the economic ladder because poorer people spend a higher percentage of their wealth than their richer counterparts. Property taxes also tilt toward the wealthy, who typically own valuable property, but relative to their overall wealth, any one piece of real estate is proportionately less of their total assets than for the typical homeowner.

By depending so heavily on the lower economic strata to cover revenue needs, governments at all levels are setting themselves up for cash flow shortfalls. In fact, since 2000, tax revenue as a percentage of GDP has declined in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Israel, Norway, Sweden, and the United States.9 With less money in government coffers, education and other social needs like infrastructure improvements or upskilling job training are by necessity starved. Regressive tax systems—in name or in actuality—ultimately pit the rich against the poor, creating a resentment gap between people who have the money to pay for whatever they need and less wealthy people who are unable to save to cover, say, college tuition. In the context of education, fewer tax receipts results in inadequate schools, which turn out graduates who are ill-prepared to contribute to technological innovation, organizational breakthroughs, and cultural creativity that are needed to juice economic growth. As the economy ebbs, tax yields fall in concert.

Without sufficient tax revenue to fund public universities, an alternative is to raise tuition at these schools. But that is not a viable option anymore, in part because of the demographic crisis. This is particularly true in Western countries where the population is aging and thus the number of domestic students is declining. Increasing prices is obviously not an answer to falling demand. With the deeper international relationships formed by globalization slowly fracturing, fewer overseas students are applying to nondomestic schools; indeed, some of them are restricted from doing so by immigration policies promulgated by nationalist governments. Perhaps most important, raising public university tuition may not be a good idea under any circumstances: it harms the students these schools are most intended to help get an education as the least well-off enrollees are either shut out by higher costs or have to incur high amounts of debt to pay their way through school, leaving them further behind upon graduation.

Finally, universities could potentially solve some of the revenue shortfall by developing programs that target the lifelong learning needs of adults, especially in a period of technological disruption when reskilling is an imperative for many. But few schools have even begun to consider this potential group of students and big institutions are slow to change; the exceptions are the few fortunate enough to have leaders like Jin Naibing to put themselves on the line in the service of radical transformation.

![]()

When functioning well, our institutions make us stronger; they provide the social goods and essential services that make society work. And they are at risk. If they were businesses, we could simply let them fail to eventually be replaced by something else. The problem is they are critical elements of society that provide the basic fabric that makes things work. Thus their potential failure, or even significant performance problems, is a crisis for society that needs to be addressed across a broad swath of our institutions by the people responsible for those institutions at the local, regional, and national levels. We only miss the glue that holds things together when it is gone. When we really notice institutions are not working, it may be too late.