15

The Nature of the Change Process

CHAPTER OUTLINE

• Perspectives on Change for HRD

• Incremental versus Transformational Change

• Continuous versus Episodic Change

• Case Example: Organizational Change

• Sociotechnical Systems Theory

Focused Perspectives on Change

Introduction

Change has been a central concept in human resource development (HRD) from the beginning. Individual change and organizational change are the basic change perspectives in HRD.

Individual change models focus narrowly on ways that individuals change. While this may affect an organization, the primary emphasis is on the individual and helping the individual change herself or himself. Individual learning and expertise development through T&D can be seen as a particular type of change at the individual level, especially transformational learning. Career development specialists focus on helping people change their lives and jobs over a longer term. Adult development theory focuses on the many ways that adults change throughout their life. While none of these are usually thought of as change theory, change is the overarching construct that unites them within HRD.

Organization change models embrace the individual but within the larger context of changing the organization. Most of these models emerge from what is generically known as organization development (OD). OD professionals specialize in change, usually at the group, work process, or organization levels.

Thus, all HRD professionals can be seen as leading or facilitating change for the goal of improvement (Holton, 1997). This chapter’s purpose is to examine change as an organizing construct for human resource development in its effort to contribute to performance requirements. This chapter focuses on the core understandings of the change process that cut across all areas of practice and research and not the specific contexts of change.

PERSPECTIVES ON CHANGE FOR HRD

Change is a familiar concept but is seldom explicitly defined. It is important to understand what is meant by change.

Change as Individual Development Some definitions of change focus first on the fact that change in organizations always involves changing individuals: “Induction of new patterns of action, belief, and attitudes among substantial segments of a population” (Schein, 1970, 134). From this view, organizational change involves getting people in organizations to do, believe, or feel something different. It is this view of change that has dominated training-oriented change interventions.

Change as Learning The second definition of change speaks to how change occurs: “Change is a cyclical process of creating knowledge (the change or innovation), disseminating it, implementing the change, and then institutionalizing what is learned by making it part of the organization’s routines” (Watkins and Marsick, 1993, 21). This definition reminds us that change usually involves learning. “Learning and change processes are part of each other. Change is a learning process and learning is a change process” (Beckhard and Pritchard, 1992, 4). This fundamental relationship points out why change is one of the core constructs for the discipline of human resource development.

Change as Career Development Within career development, there is some disagreement about the exact definition of a career. Here are two leading definitions:

The evolving sequence of a person’s work experiences over time (Osipow and Fitzgerald, 1996, 51)

The combination and sequence of roles played by a person during the course of a lifetime (Super, 1980, 282; Super and Sverko, 1995, 23)

The point of agreement is that a career is conceptualized as the sequence of roles a person fills. The point of disagreement is whether those changes include just work roles or work and life roles. Regardless, career development is fundamentally concerned with change and evolution of a person’s roles.

Change as Internal Adult Development Another view of change comes from adult development theory. The generally accepted notion that adults continue to develop throughout the life span—biologically, psychologically, cognitively, and socially—links adult development with change (McLagan, 2017). “The concept of development, as with learning, is most often equated with change” (Merriam and Caffarella, 2006, p. 93). Adult development theory defines the types of internal changes that adults experience in their lives in contrast to career development theory, which defines the roles adults fill in society.

Change as Goal-Directed Activity The previous definitions offer little guidance toward the purpose of change. Other definitions suggest that change should have a purpose: “Change is a departure from the status quo. It implies movement toward a goal, an idealized state, or a vision of what should be, and movement away from present conditions, beliefs, or attitudes” (Rothwell, Sullivan, and McLean, 1995, 9). Change should therefore be directed at some goal or outcome that represents a vision of a more desirable end state. However, they remind us that not all change is good. Change can be in negative directions, resulting in a less effective organization if it is not focused on desired outcomes.

Change as Innovation Poole and Van de Ven (2004) define organizational change as “a difference in form, quality, or a state over time in an organizational entity (xi). Equally purposeful is the definition of innovation in organizations: “The innovation journey is defined as new ideas that are developed and implemented to achieve outcomes by people who engage in transactions (relationships) with others in changing institutional and organizational contexts” (Van de Ven, Polley, Garud, and Venkataraman, 2008, 7). Change in these definitions consists of new ideas implemented in a social process directed at achieving outcomes to change organizations.

Core Dimensions of Change

Two core dimensions of change are important to consider: the depth of change (incremental vs. transformational) and the tempo of change (continuous vs. episodic).

INCREMENTAL VERSUS TRANSFORMATIONAL CHANGE

The distinction between incremental and transformational change is concerned with the depth and scope of change. Incremental change deals with smaller, more adaptive changes, while transformational change requires major shifts in direction or perspective. This distinction is found in organization development and adult learning literature. Not surprisingly, the two are closely aligned.

OD and Planned Incremental Change A fundamental issue for OD has been the scope of change in which its tools are applied. The traditional focus of OD has been on planned incremental change. The OD approach is distinguished from other organization change approaches in this way:

OD and change management both address the effective implementation of planned change. They are concerned with the sequence of activities, processes and leadership issues that produce organizational improvements. They differ, however, in their underlying value orientation. OD’s behavioral science foundation supports values of human potential, participation, and development, whereas change management is more focused on economic potential and the creation of competitive advantage. As a result, OD’s distinguishing feature is its concern with the transfer of knowledge and skill such that the system is more able to manage change in the future. Change management does not necessarily require the transfer of such skills. In short, all OD involves change management, but change management does not involve OD. (Cummings and Worley, 2001, 3; emphasis added)

The change process that lends itself best to the values of human potential, participation, and development is incremental change. That is, change that “produces appreciable, not radical, change in individual employees’ cognitions as well as behaviors” (Porras and Silvers, 1991).

The traditional emphasis on planned incremental change has limited OD’s influence on organizational change. This presents a perplexing dilemma for HRD. The philosophical ideals of human potential, participation, and development embedded in the OD approaches to change are also ones traditionally embraced by HRD professionals. Most OD professionals have now embraced more holistic models of change (Poole and Van de Ven, 2004).

Transformational Change Transformational change has increasingly moved to the forefront of organizational and individual change and is defined as an:

extension of organization development that seeks to create massive changes in an organization’s structures, processes, culture, and orientation to its environment. Organization transformation is the application of behavioral science theory and practice to large-scale, paradigm-shifting organizational change. An organization transformation usually results in totally new paradigms or models for organizing and performing work. (French, Bell, and Zawacki, 1999, vii)

Indeed, transformational change goes well beyond the incremental change characterized by traditional OD and is the more recent addition to OD practice. Transformational change has five key characteristics (Cummings and Worley, 2001):

1. Triggered by environmental and internal disruptions—organizations must experience a severe threat to survival.

2. Systemic and revolutionary—the entire nature of the organization must change, including its culture and design.

3. Demands a new organizing paradigm—by definition, it requires gamma change (discussion to follow).

4. Is driven by senior executives and line management—transformational change cannot be a “bottom-up” process because senior management is in charge of strategic change.

5. Continuous learning and change—the learning process will likely be substantial and require considerable unlearning and innovation.

Clearly, this type of change does not lend itself to traditional OD methodologies. Sometimes transformational change threatens traditional OD values because it may entail layoffs or significant restructurings. In addition, it is not always possible to have broad participation in planning transformational change, and it is often implemented in a top-down manner.

More recent methods have emerged in an attempt to expand OD’s reach into large-scale whole-systems change in a manner that is consistent with OD values (Bunker and Alban, 1997). These include techniques such as future search (Weisbord and Janoff, 2007), open space technology (Owen, 2008), real-time strategic change (Jacobs, 1994), and the ICA strategic planning process (Spencer, 1989).

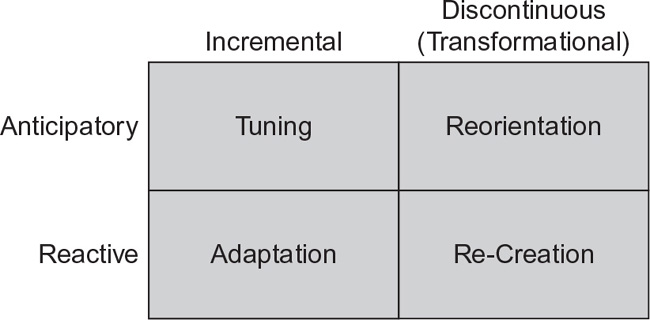

Incremental and transformational change can be implemented in reaction to events (reactive) or in a proactive way in anticipation of events that may occur (anticipatory) (Nadler and Tushman, 1995). Thus, Nadler and Tushman suggest four types of change: tuning, adaptation, reorientation, and re-creation (see figure 15.1). Adaptation, which is reactive incremental change, is probably the most common type of change and constantly occurs in organizations. Re-orientation, which is anticipatory transformational change, is the most challenging type to implement.

Figure 15.1: Types of Organizational Change

CONTINUOUS VERSUS EPISODIC CHANGE

Another critical dimension of change is its tempo, defined as the rate, rhythm, or pattern of the change process. The first tempo, continuous change, is described as “a pattern of endless modifications in work processes and social practices. . . . Numerous small accommodations cumulate and amplify” (Weick and Quinn, 1999, 366). Continuous change has historically been closely related to incremental change but is actually a different construct, which has an important implication in today’s fast-changing world.

The second tempo, episodic change, is defined as “occasional interruption or divergence from equilibrium. . . . It is seen as a failure of the organization to adapt its deep structure to a changing environment” (Weick and Quinn, 1999, 366). Episodic change tends to be infrequent and occurs in short-term episodes. In this view, organizations have a certain amount of change inertia until some force triggers them.

While this description is close to the definition of incremental versus transformational change, considering tempo of change (continuous vs. episodic) separately from the scope of change (incremental vs. transformational) is useful. The problem is that deep change is defined as episodic. In today’s world, companies like internet-based firms have to make continuous transformational change, which is not even contemplated in the original definitions. The notion that transformational change only occurs episodically has been true historically but is increasingly challenged today. Furthermore, it is also possible for organizations to make an episodic change that is only incremental rather than transformational. Corporate management teams are viewed as most likely to lead to incremental change—even when attempting strategic change—that ultimately causes them to overlook disruptive changes, technological and otherwise, that threaten their business (Christensen, 1997).

Change Outcomes

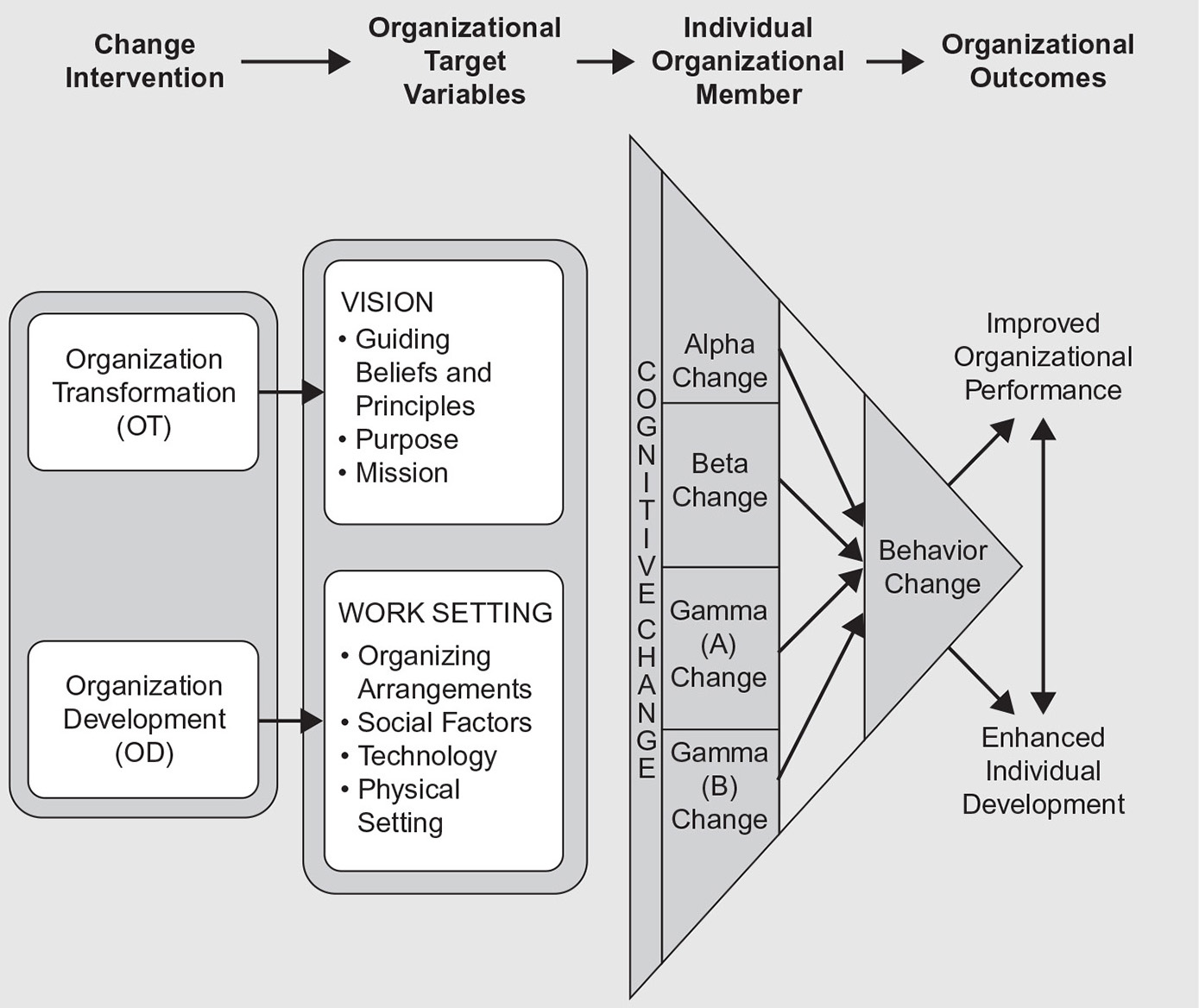

When considering the multitude of individual, process, group, and organizational dimensions that can be affected, the possible outcomes from change are enormous. A more fundamental way to describe outcomes from change is through four basic types of change (Porras and Silvers, 1991, 57):

• Alpha change—change in the perceived levels of variables within a paradigm without altering their configuration (e.g., a perceived improvement in skills).

• Beta change—change in people’s view about the meaning of the value of any variable within an existing paradigm without altering their configuration (e.g., change in standards).

• Gamma(A) change—change in the configuration of an existing paradigm without the addition of new variables (e.g., changing the central value of “production-driven” paradigm from “cost containment” to “total quality focus”). This results in the reconfiguration of all variables within this paradigm.

• Gamma(B) change—the replacement of one paradigm with another that contains some or all of new variables (e.g., replacing a “production-driven” paradigm with a “customer-responsive” paradigm).

General Theories of Change

In this section, three general theories of change are discussed. Most other theories or models of change processes can be located within these three basic frameworks.

FIELD THEORY

The classic general theory of change is Kurt Lewin’s (1951) field theory. This theory has influenced most change theories. The essence of field theory is deceptively simple and enduring.

The most fundamental construct in this theory is the field. According to Lewin, “All behavior is conceived of as a change of some state of a field in a given unit of time” (xi). For individuals, he says this is “the ‘life space’ of the individual. This life space consists of the person and the psychological environment as it exists for him” (xi). It is helpful to realize that a field also exists for any unit of social structure or organization. Thus, a field can be defined for a team, department, or organization.

The field or life space includes “all facts that have existence and excludes those that do not have existence for the individual or group under study” (xi). This is vitally important in considering change because individuals or groups may have distorted views of reality or may not see certain aspects of reality. What matters to the person or group and what shapes their behavior is only what they see.

CASE EXAMPLE: ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE

Suppose you are dealing with an organization with declining performance (e.g., profits) requiring some organizational change. An example of alpha change would be for them to focus on doing a better job at what they are already doing, perhaps by eliminating errors and waste. Beta change would result if the organization realized that the industry had become so competitive that their previous notions of what high performance meant had to be revised upward. An example of gamma(A) change might be introducing enterprise software to run their business more effectively but requiring a reorganization of their work processes. Gamma(B) change would result if they discarded their old business model of selling through retail stores and replaced it with one selling through the internet.

This case is helpful because these different types of outcomes clearly would require different change strategies. These are portrayed in the model shown in figure 15.2 (Porras and Silvers, 1991). Note that they begin with two basic types of change interventions discussed earlier: organization development (incremental) and organization transformation. The target variables are those at which interventions are aimed. As a result of the interventions on these target variables, alpha, beta, or gamma cognitive change results in individual members leading to enhanced individual development and improved organizational performance.

Figure 15.2: Model of Change Outcomes

Source: Porras and Silvers, 1991, 53. Used with permission.

Finally, field theory acknowledges that behavior is not dependent on what happened in the past or what is expected to happen in the future but rather on the field as it exists in the present. Lewin did not ignore the effects of history or anticipated events. Instead, he said that it is how those past or anticipated events manifest themselves in the present that affects behavior. In other words, it is how those events are perceived today that is part of a person’s field and influences the person’s behavior today.

According to field theory, change is the result of a constellation of psychological forces in a person’s field at a given point in time. Driving forces are those that push a person toward a positive outcome while restraining forces are those that represent barriers. Driving forces push a person toward movement, while restraining forces may inhibit locomotion. Forces in a person’s field create tension. If the driving and restraining forces are equal and opposite, conflict results and no motion is likely to result. Thus, to understand a person or group’s likelihood of changing, driving forces have to be stronger than restraining forces. A field where the forces are approximately in balance results in a quasi-equilibrium state where no change is likely.

Perhaps the best-known part of Lewin’s field theory is his three-step change process: unfreezing, movement, and refreezing. However, it is rarely discussed in field theory, which is the most helpful way to understand it.

From the preceding discussion, it would appear that all one has to do to invoke change is to increase driving forces or decrease restraining forces, and a proportional change would result. According to Lewin, this is not the case. Social systems in a quasi-equilibrium develop an inner resistance to change, which he calls a social habit or custom. In force terms, the equilibrium level acquires a value itself, becoming a force working to maintain that equilibrium. Furthermore, “the greater the social value of a group standard the greater is the resistance of the individual group member to move away from this level” (227).

To overcome this inner resistance, Lewin says that “an additional force seems to be required, a force sufficient to ‘break the habit,’ to ‘unfreeze’ the custom” (225). In other words, to begin the change process, some larger force is necessary to break the inherent resistance to change. The unfreezing force will result in a less than proportional movement, but it will begin movement toward a new equilibrium. Lewin also notes that this is one reason group methods are so powerful in leading change. Because the inner resistance is often group norms, change is more likely to happen if the group can be encouraged to change those norms themselves.

Lewin goes on to note that change is often short-lived. After exerting the effort to unfreeze a group, change may occur, but then people revert to the previous level. Therefore, equal attention must be paid to what he called freezing, usually referred to today as refreezing, rather than just moving people to a new level. Lewin defines freezing as “the new force field is made secure against change” (229). Freezing involves harnessing the same power of the social field that acted to prevent change in the beginning by creating new group norms that reinforce the changes.

SOCIOTECHNICAL SYSTEMS THEORY

Sociotechnical systems theory was developed by Eric Trist and was based on work he did with the British coal mining industry while he was at the Tavistock Institute (Fox, 1995). First presented in the early 1950s (Trist and Bamforth, 1951), it, too, has stood the test of time and remains at the core of most organizational development change efforts. Trist and Bamforth were studying a successful British coal mine when most of the industry was experiencing a great deal of difficulty, despite large investments to improve mining technology. They observed that this particular mine had improved the social structure of work (to autonomous work teams), not just to the technology. They realized that the cause of much of the industry’s problems was a failure to consider changes in the social structure of work to accompany the technical changes being made. While this may sound obvious, the same mistake is still being made today. For example, many organizations have struggled to implement software systems mainly because they have approached them as a technology problem without considering the people aspects.

From that work emerged the relatively simple but powerful concept that work consists of two interdependent systems that have to be jointly optimized. The technical system consists of the materials, machines, processes, and systems that produce the organization’s outputs. The social system is the system that relates the workers to the technical system and each other (Cooper and Foster, 1971). Usually, organizational change initiatives emphasize one more than the other. Typically, the technical system is highlighted more than the social system because it is easy to change computers, machines, or buildings and ignore the effect of the change on people.

Sociotechnical systems have remained a loosely defined metatheory without detailed explication. Instead, the intent and elements of sociotechnical systems theory are present in detail in many change models, such as total quality management reengineering (Shani and Mitki, 1996) and the enterprise model (Brache, 2002). Thus, sociotechnical systems provide a handy framework for organizational analysis and change.

TYPOLOGY OF CHANGE THEORIES

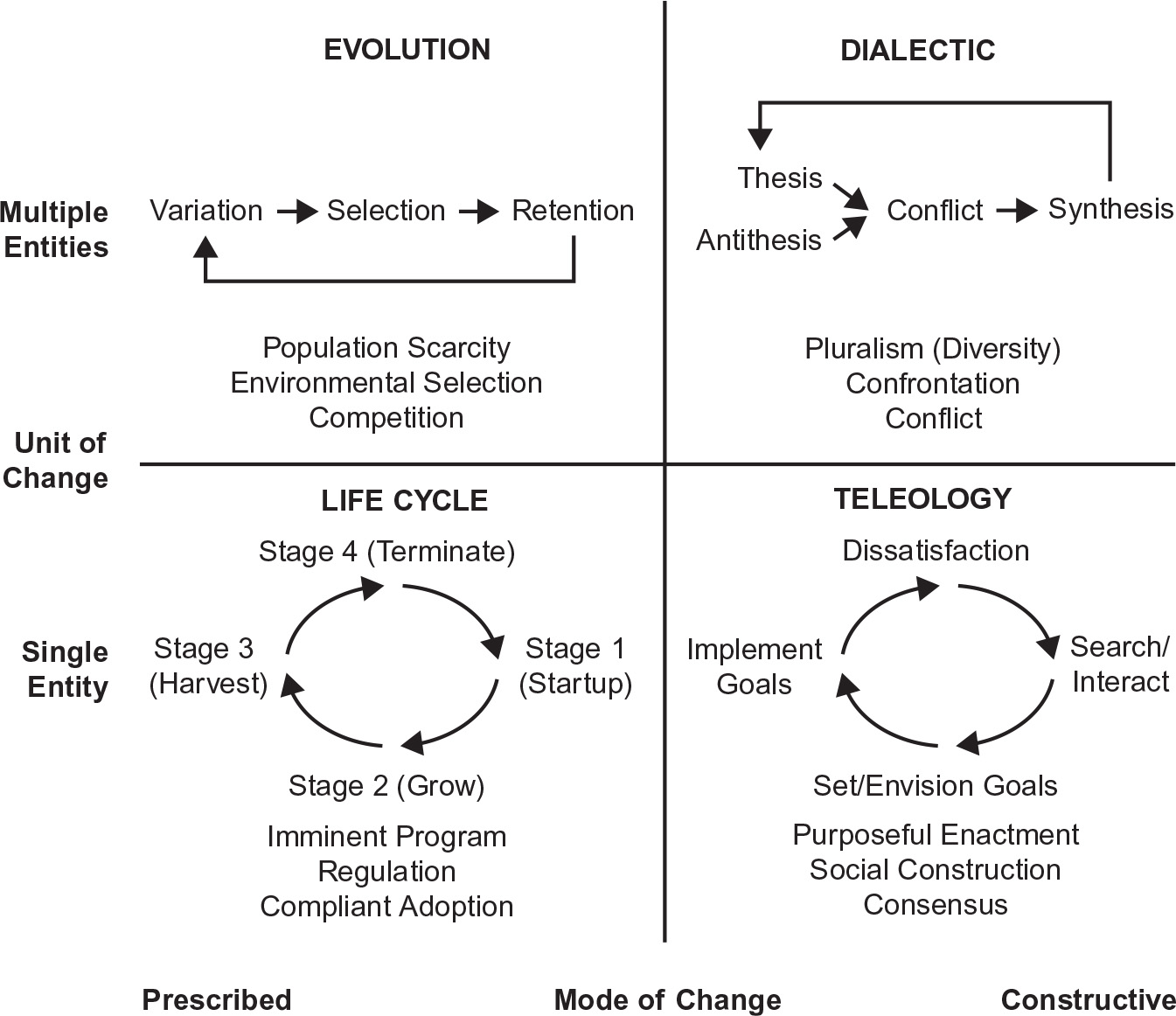

Van de Van and Poole (2005) present four basic process theories of change that they say underlie change in the social, biological, and physical sciences. They contend that these four schools of thought about change are distinctly different and that all specific theories of organizational and individual change can be built from one or a combination of these four. As a result, these four offer a more parsimonious explanation of organizational change and development. “In each theory: (a) process is viewed as a different cycle of change events, (b) which is governed by a different “motor” or generating mechanism that (c) operates on a different unit of analysis, and (d) represents a different mode of change” (520).

Figure 15.3: Process Theories of Organizational Development and Change

Source: Van de Ven and Poole, 1995, 520. Used with permission.

This four-part framework is beneficial for understanding the variety of change theories in the literature (figure 15.3). Using these four general theories, you can find the commonalities among diverse approaches. It is helpful in practice because it enables one to understand the multiple forces for change that occur. Van de Ven and Poole (2005) also identify sixteen possible combinations of these four theories that represent logically possible composite theories.

Life cycle theory depicts change as progressing through stages governed by a natural or logical “law” that prescribes the stages. For example, life cycle theories of organizations (Adizes, 1988) project certain critical stages that every firm experiences as it grows from a small company to a larger, more complex organization.

Teleological theory also operates within a single entity but offers constructive rather than prescribed stages of change. Teleological theory views development as a cycle of goal formulation and implementation. Individuals within the entity construct these goals. Strategic planning could be a classic example of this theory whereby an organization sets goals for its future and works to implement them. Career planning might be an individual-level teleological theory.

Evolutionary theory differs from the previous two in that it operates on multiple entities. This model views change as occurring out of competition for scarce resources within the entity’s environment. As a result, entities within the population go through cycles of variation, selection, and retention. That is, some grow and thrive; some decline or die. These cycles are somewhat predictable, so the change process is prescribed in these theories. Theories of organization development that focus on external competitive forces and how firms thrive or die within competitive environments fall within this theory.

Dialectic theory also operates on multiple entities but with constructed change processes. In this model, change arises out of conflict between entities espousing opposing thesis and antithesis. Change occurs through the confrontation and conflict that results. Many instances of organizational change that arise due to changes in societal norms fit within this framework. For example, changes in the workplace reflecting racial, gender, and ethnic diversity often arise out of dialectical tensions.

Resistance to Change

“All change requires exchanging something old for something new. People have to unlearn and relearn, exchange power and status, and exchange old norms and values for new norms and values. These changes are often frightening and threatening, while at the same time [are] potentially stimulating and providers of new hope” (Tichy, 1983, 332). The notion of exchange is particularly important because there are costs and benefits to each side of the exchange. Ultimately, the benefits have to outweigh the costs for change to succeed.

NATURE OF RESISTANCE

Resistance to change is a universal phenomenon, whether one is implementing a new strategy in an organization or helping individuals lose weight. In fact, without resistance, change would not be difficult, and many change interventions and models would be greatly simplified. It is resistance that shapes most change strategies and makes effective change leaders so valuable. If the causes of resistance are understood, then strategies to overcome them become clearer.

Resistance is a multidimensional phenomenon. Piderit (2000) summarizes the resistance-to-change literature and proposes that resistance to change consists of three dimensions:

• Cognitive—beliefs about the change

• Emotional (affective)—feelings in response to change

• Behavioral—actions in response to change

This three-part view of resistance is particularly important because a person may not be consistent on all three dimensions. If a person is negative on all three dimensions, resistance occurs. If positive on all three dimensions, support for change occurs. However, it is not uncommon for a person to be conflicted. For example, a person may believe change is needed (cognitive) but still fear it (affective). Or, a person may not believe in it and fear it but act as if they support the change. Piderit (2000) calls this ambivalence, defined as the state where two alternative perspectives are both strongly experienced (787). She also suggests that this phenomenon may be more widespread during change than is acknowledged.

Tichy (1983) approaches organizational change from three aspects of organizational reality: the technical, political, and cultural views. The technical perspective focuses on organizing to get the work accomplished most effectively. The political view focuses on power and the allocation of rewards. The cultural view focuses on the norms and values in the organization.

FORMS OF RESISTANCE

Probably the most vexing question in the literature is why resistance to change occurs. King and Anderson (1995) suggest four fundamentally different views of causes of resistance in the literature. We will explore each in the following sections.

Resistance as Unavoidable Behavioral Response This is probably the dominant view of resistance to change. In this view, individuals resist change simply because it represents a move into the unknown. Therefore, resistance is a natural and unavoidable response. The fact that individuals have a strong need to hold onto what is familiar is a powerful force, a point that has been neglected in the change literature (Tannenbaum and Hanna, 1985). This deep-seated need to hold on may be the root cause of much resistance to change. Tannenbaum and Hanna (1985) suggest that there are four primary reasons for this need:

• Change is loss, requiring us to let go of something familiar and predictable.

• Change is uncertainty, requiring us to move from the known to the unknown.

• Change dissolves meaning, which in turn affects our identity.

• Change violates scripts, disrupting our unconscious life plans.

Change leaders who understand the natural psychological process individuals undergo can facilitate letting go and moving on. Those who ignore it encounter resistance to change that may seem insurmountable.

Resistance as Political and Class Struggle The most radical of the four views, this view holds that resistance stems from the fundamentally inequitable relationship between workers and the organization. Because workers often feel alienated and exploited, they sometimes resist change that benefits the organization. King and Anderson (1995) suggest this type of resistance may be more prevalent among labor groups who feel most alienated from management and the organization. For example, some unions have been known to resist change because it is perceived to exploit workers. Also, one of the chief criticisms of corporate restructuring is that it has exploited employees in organizations and rewarded top executives (Economist, 2008). As a result, many employees were reluctant to embrace other changes proposed in those organizations.

Resistance as Constructive Counterbalance From this view, resistance may not always be a bad thing but instead acts as a counterbalance to change that is ill-conceived, poorly implemented, or viewed as detrimental to the organization. Resistance to change has most often been discussed from a managerial point of view whereby resistance is seen as a barrier employees present to management’s change initiatives and something that must be overcome. However, implicit in that traditional view is that management is “right” and employees are “wrong” when it comes to change. Yet, management’s change initiatives frequently may not be the right course of action, and resistance is a healthy response by the organization to ill-conceived change. Thus, resistance may not be harmful but instead serve as a check-and-balance system to prevent poorly conceived change from destroying the organization.

This is supported by evidence that employees are increasingly cynical about change (Reichers, Wanous, and Austin, 1997). According to Reichers, Wanous, and Austin, cynicism about change is different from resistance in that it involves a loss of faith in leaders of change due to a history of failed attempts at change. It is related to poorer job attitudes and motivation. A common cause of this is a history of “program-of-the-month” types of change efforts. Cynicism may lead to resistance, which is usually viewed negatively by employees. However, if an organization has a history of “program-of-the-month” change efforts, then resistance may be a valuable counterbalance to force management to think more carefully before proposing new change.

Resistance as Cognitive and Cultural Restructuring In this perspective, resistance is conceived as a byproduct of restructuring cognitive schemas at the individual level and as a recasting of organizational culture and climate at the organizational level. The paradox is that individuals and organizations seek both change and stability (Leana and Barry, 2000). Individual schemas help people maintain a sense of identity and meaning in their day-to-day activities. Yet, change is also necessary to prevent boredom. Organizational schemas are necessary for efficient daily operation and help perpetuate successful practices. Continuous change is required to adapt to fast-changing environments. Thus, there is always a tension between maintaining schemas and changing them when necessary.

The focus on individual schema has increased, in part due to Senge’s (1990) earlier popular work on the learning organization in which he cites mental models (a closely related term) as one of his five disciplines. He defines mental models as “deeply held internal images of how the world works, images that limit us to familiar ways of thinking and acting” (174). In other words, mental models are the cognitive structures that arise from an individual’s experiences. While they help employees become more efficient, they also impede change because many people resist changes that do not fit their mental model, particularly if change involves restructuring long or deeply held schema.

Argyris (1982, 1999) describes two fundamental theories (mental models) that people use to guide action in organizations. Model I, as he calls it, has four governing values: (1) achieve your intended purpose, (2) maximize winning and minimize losing, (3) suppress negative feelings, and (4) behave according to what you consider rational. This theory leads people to advocate their positions and cover up mistakes, which he calls defensive routines. Defensive routines are blocks to individual and organizational learning. Model II, on the other hand, is predicated on the open sharing of information and detecting and correcting mistakes. As a result, defensive routines are minimized, and genuine learning is facilitated. The ability to change the schema or mental models has been linked to a firm’s ability to engage in strategic change and renewal (Barr, Stimpert, and Huff, 1992). Unfortunately, model I is predominant in most organizations, serving as a fundamental source of resistance to change. Conversion to model II usually requires double-loop learning.

Similarly, the role of organizational culture in blocking or facilitating change is widely recognized. Changing culture remains one of the most difficult challenges in organizational change. Organizational culture, which is usually deeply rooted, can be a tremendous source of resistance to change. It represents organizational mental models of shared assumptions about how the organization should function.

As Schein (2010) points out, “changing something implies not just learning something new but unlearning something that is already there and possibly in the way” (116). He equates the unlearning process to overcoming resistance to change. In the case of major change, such as changing culture, change has to begin with some disconfirmation such that survival anxiety exceeds learning anxiety. If so, then cognitive redefinition results for the learner.

In summary, resistance to change is a complex but vitally important change construct. Whether viewed from the individual, group, or organizational level, addressing resistance to change is a central concern for theory and practice.

Focused Perspectives on Change

Numerous middle-range theories have arisen alongside the general theory of change to describe change from a particular perspective or lens. Each lens is instructive and valuable for understanding change in more depth. This section is not intended to be a comprehensive review but rather to present several focused theories representative of major perspectives.

ORGANIZATIONAL THEORIES

Four theories are presented here: organizations as performance systems, the Burke-Litwin model, innovation diffusion theory, and the organizational communications approach.

Organizations as Performance Systems Thinking about the organization as a performance system functioning within the larger environment and as a collection of subsystems has been the work of numerous organizational scholars, including Senge’s (1990) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization and Wheatley’s (1999) Leadership and the New Science: Learning about Organization from an Orderly Universe. Both influential pieces have minimal direct connections of their theories to the substantive work of change.

In contrast, Rummler and Brache’s (1995) and Brache’s (2002) holistic and systemic views of the organization as a performance system intricately bridge the theory-practice gap. The entire model is discussed in more detail in chapter 9. They begin by viewing organizations as adaptive systems.

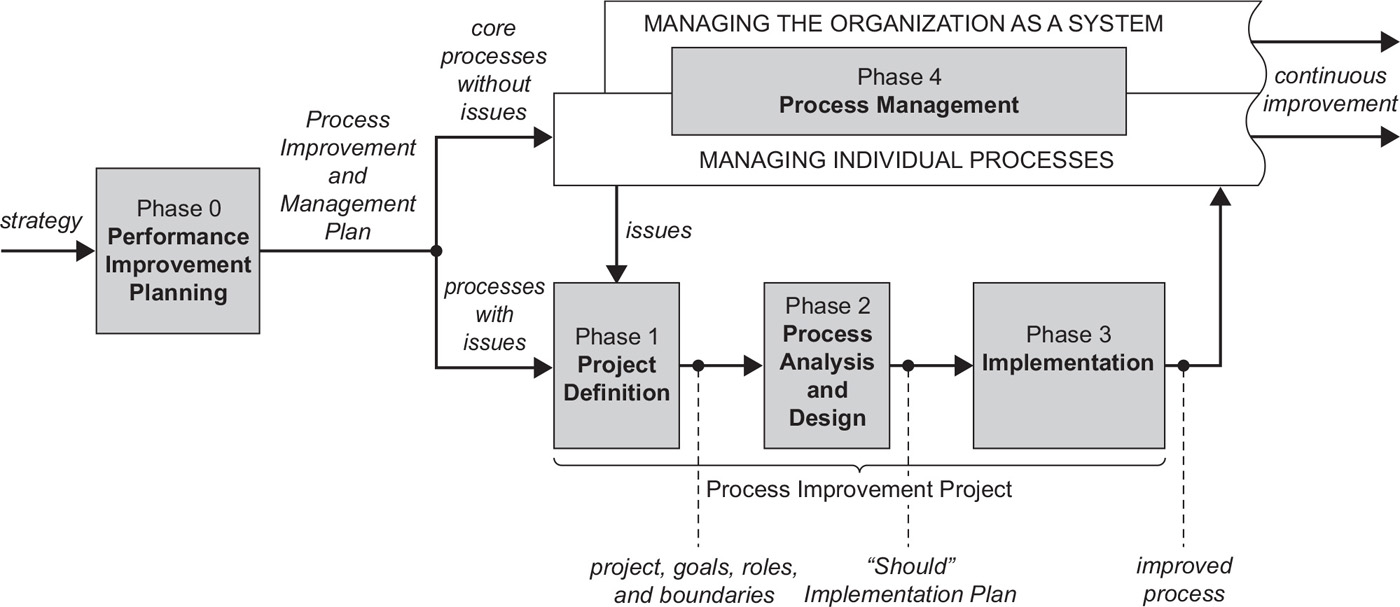

As the Rummler and Brache inquiry model unfolds, the organization, work process, and individual contributor performance levels are laid out. In addition, the three performance needs of goals, design, and management are specified. The resulting 3 × 3 matrix creates nine performance cells (see figure 15.4). Together they create a framework for thinking about the performance variables that impinge upon change. Their overall methodology is portrayed in figure 15.4.

The Rummler and Brache change process is aimed at organizational performance, and it is both a theoretically sound organization development change process (see Wimbiscus, 1995) and one that has been proven in practice. It combines thinking models, systemic relationships, tools, and metrics to guide the change effort. More than most change models, the Rummler and Brache model requires the OD consultant and the improvement team to be serious students of the organization, its larger environment, and the inner working of the organization’s processes and people.

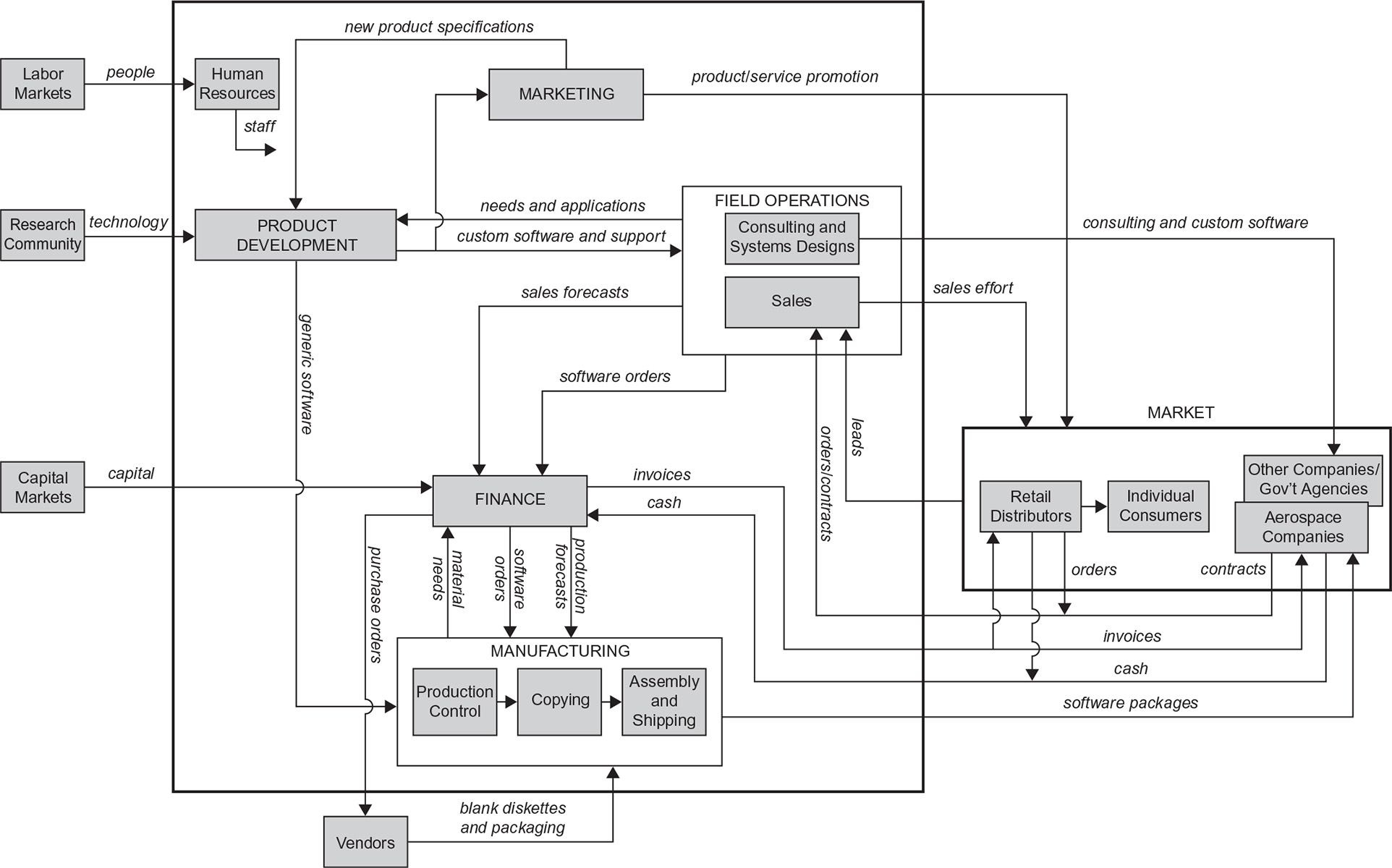

A relationship map of a hypothetical computer company is presented in Figure 15.5 to illustrate an early analysis step of their change process.

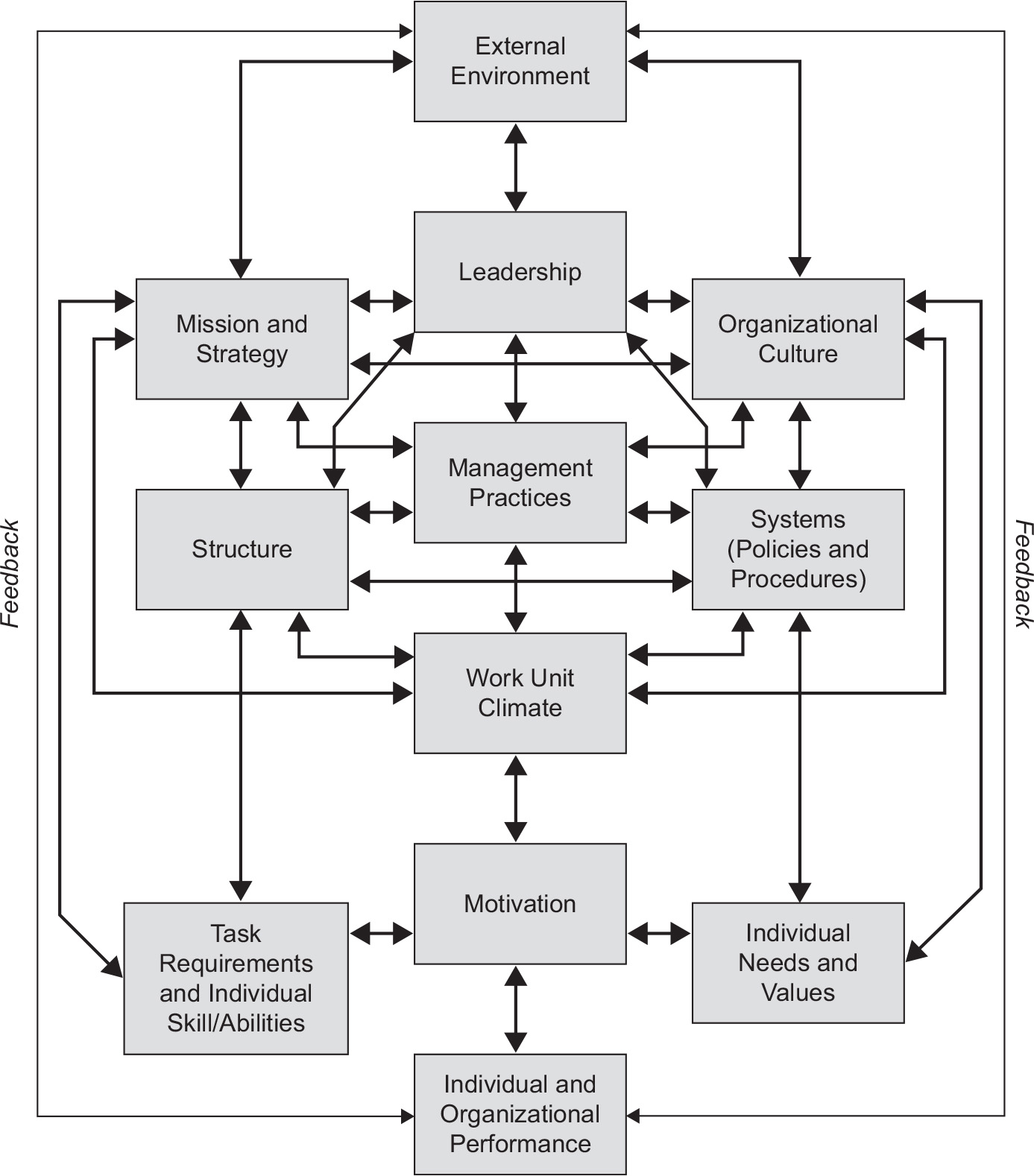

Burke-Litwin Model of Organizational Performance and Change One of the more complex but comprehensive models of organizational change is the Burke–Litwin (1992) model. Burke and Litwin attempted to capture the interrelationships of complex organizational variables and distinguish between transformational and transactional dynamics in organizational change (Burke, 1994). Furthermore, the model portrays the primary variables or subsystems that predict and explain performance in an organization and how those subsystems affect change. Figure 15.6 shows the complete model.

Figure 15.4: Process Improvement and Management Methodology

Source: Rummler and Brache, 1995, 117. Used with permission.

Figure 15.5: Relationship Map for Computec, Inc.

Source: Rummler and Brache, 1995, 38. Used with permission.

The top part of the model shows the transformational subsystems: leadership, mission and strategy, and organizational culture. Change in these areas is usually caused by interaction with the external environment and requires entirely new behavior by the organization. For organizations that need significant change, these are the primary levers. The lower part of the model contains the transactional subsystems: management practices, systems, structure, work unit climate, motivation, task requirements and individual skills/abilities, and individual needs and values. Change in these areas occurs primarily through short-term reciprocity among people and groups. For organizations that need a fine-tuning or improving change process, these subsystems are the primary levers. The arrows in the model represent the causal relationships between the major subsystems and the reciprocal feedback loops. Burke and his associates have also developed a diagnostic survey that can assess and plan change using the model.

Figure 15.6: Model of Organizational Performance and Change

Source: Burke and Litwin, 1992, 528. Used with permission.

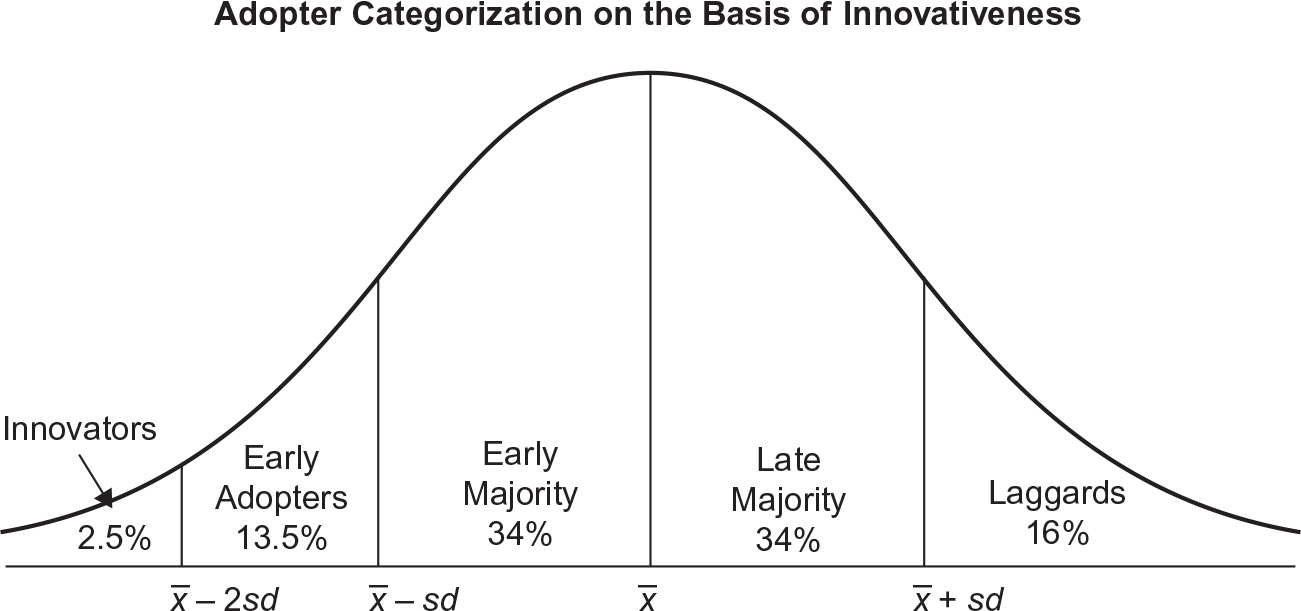

Innovation Diffusion Theory Diffusion research focuses on factors influencing the rate and extent to which change and innovation are spread among and adopted by members of a social system (e.g., organization, community, society, etc.). Rogers (1995) offers the most comprehensive and authoritative review of diffusion research. He defines diffusion as “the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among members of a social system” (10). The four key components of a diffusion system embedded in this definition are innovation, communication channels, time, and the social system.

The body of research on diffusion is immense and is often overlooked by HRD professionals. An instrumental part of this research is the rate at which change is adopted in social systems. It turns out that the rate is reasonably predictable and almost always follows a normal distribution, as shown in figure 15.7.

Rogers defines five categories of adopters (of change or innovation):

• Innovators—venturesome with a desire for the rash, daring, and risky

• Early adopters—are respected by peers and are the embodiment of successful, discrete use of new ideas; often the opinion leader

• Early majority—tend to deliberate for some time before completely adopting a new idea but still adopt before the average person

• Late majority—approach innovation with a skeptical and cautious air and do not adopt until most others in the system have

• Laggards—tend to be suspicious and skeptical of innovations and change agents; the last to adopt and most resistant to change

Figure 15.7: Adopter Categories

Source: Rogers, 1995, 262. Used with permission.

Organizational Communications Approach Communication is central to any successful change effort. Surprisingly, few OD change models have focused on this aspect of change. Armenakis and his colleagues (Armenakis, Harris, and Mossholder, 1993; Armenakis, Harris, and Field, 1999) are a notable exception to this, offering an organizational change model built around the change message. In their view, “all efforts to introduce and institutionalize change can be thought of as sending a message to organizational members” (Armenakis, Harris, and Field, 1999, 103). The change message must have five key components that address five core questions organizational members have about the change:

Message Element | Question Answered |

Discrepancy | Is the change really necessary? |

Appropriateness | Is the specific change being introduced an appropriate reaction to the discrepancy? |

Efficacy | Can I/we successfully implement the change? |

Principal support | Are formal and informal leaders committed to successful implementation and institutionalization of the change? |

Personal valence | What is in it (the change) for me? |

Their model is considerably more complex than this, but the change message is the unique component. Also included in the model are seven generic strategies to transmit and reinforce the message: active participation, management of external and internal information, formalization activities, diffusion practices, persuasive communication, human resource management practices, and rites and ceremonies. These strategies and the message combine to move people in the organization through stages of readiness, change adoption, commitment to the change, and institutionalization.

WORK PROCESS THEORIES

The quality improvement revolution of the 1980s was led by two elderly scholar–practitioners—Dr. Joseph M. Juran and Dr. W. Edwards Deming. Both were called to help rebuild the Japanese economy after World War II and then again by the captains of American industry in the 1980s to help save the faltering economy. Their basic thesis was that producing quality goods and services ends up costing less money, increases profits, delights customers who will return for more, and provides satisfying work to people at all levels in the organization

Both of these men began their journey in the realm of change at the work process level. In addition, they started at a time when the rate of change was much slower. Over the years, they expanded their process improvement models—up to the leadership level and down to the individual worker level. Even so, the core of their work has been anchored at the work process level. A few defining features from each are highlighted here.

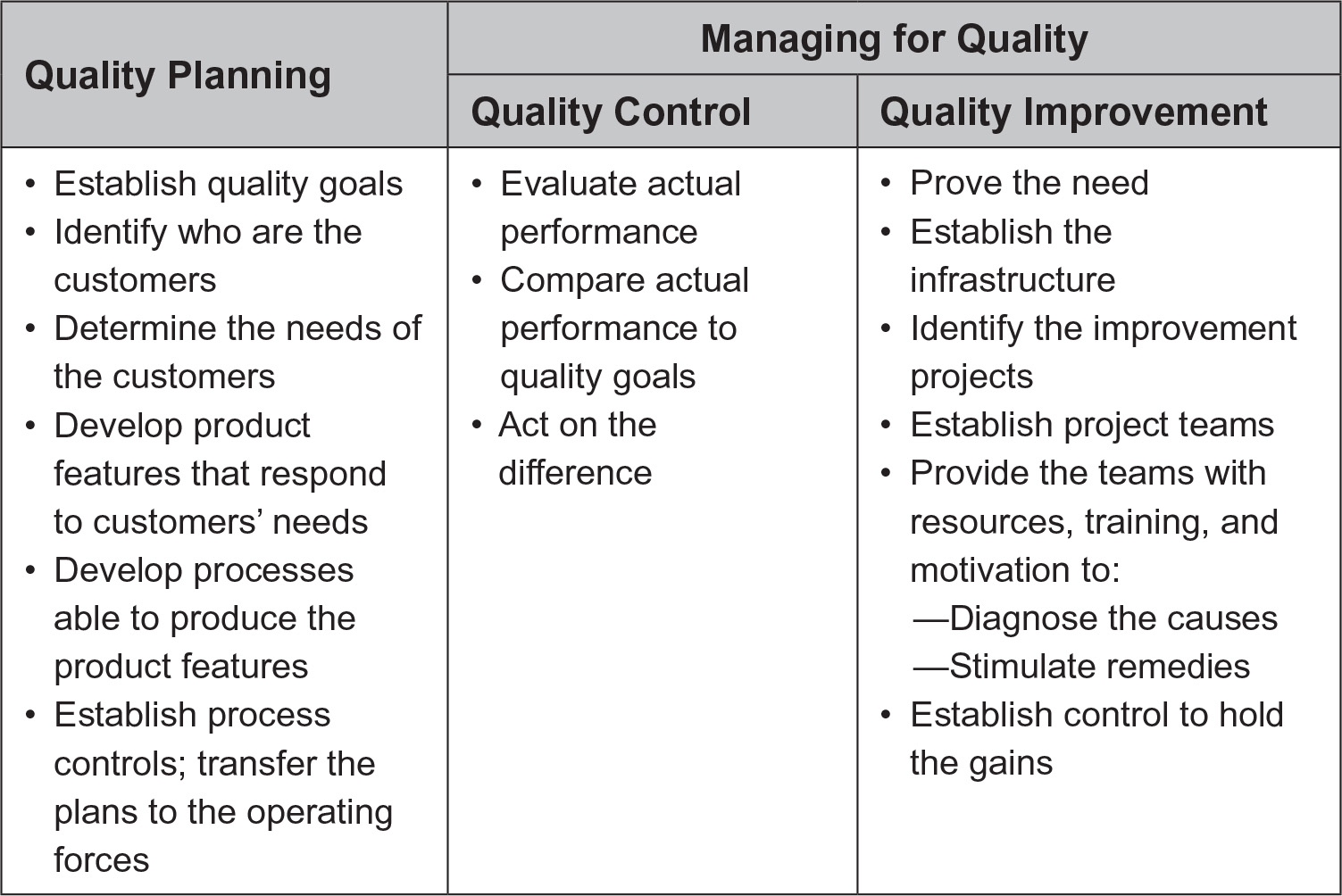

Juran’s Quality by Design At the process level, Juran (1992) defines process control and process design as follows: “Process control is the systematic evaluation of performance of a process, and taking of corrective action in the vent of nonconformance” (509). “Process design is the activity of defining the specific means to be used by the operating forces for meeting product quality goals” (221).

At the overall level, Juran identified three universal processes of managing for quality: quality planning, quality control, and quality improvement (figure 15.8).

Deming’s Fourteen Points for Management Like Juran, Deming was a statistician who relied heavily on hard data to make decisions about process improvement. He believed in documenting processes to the point that many of the flaws in the work process would simply reveal themselves. While he generally distrusted work processes that informally emerge and evolve in the work-place, he trusted numbers from good measures of those processes as the basis of improving them. He also trusted human beings and human nature—the people who work in the processes. Over time, Deming became better known for his fourteen points for management that he believed would produce saner and more productive workplaces. They are as follows:

Figure 15.8: The Three Universal Processes of Managing for Quality

Source: Juran, 1992, 16. Used with permission.

1. Create constancy of purpose for improvement of product and service.

2. Adopt a new philosophy.

3. Cease dependence on inspection to achieve quality.

4. End the practice of awarding business on price tag alone. Instead, minimize total cost by working with a single supplier.

5. Improve constantly and forever every process for planning, production, and service.

6. Institute training on the job.

7. Adopt and institute leadership.

8. Drive out fear.

9. Break down barriers between staff areas.

10. Eliminate slogans, exhortations, and targets for the workforce.

11. Eliminate numerical quotas for the workforce and numerical goals for management.

12. Remove barriers that rob people of pride in workmanship. Eliminate the annual rating or merit system.

13. Institute a vigorous program of self-improvement for everyone.

14. Put everybody in the company to work to accomplish the transformation. (Deming, 1986)

GROUP THEORIES

Group dynamics researchers have long been interested in how groups change and evolve. The result has been a plethora of sequential stage theories describing predictable stages that groups move through as they grow and develop. While they appear different on the surface, there is more agreement than disagreement among them.

Probably the best-known group change theory is described by the following five stages (Tuckman,1965; Tuckman and Jensen, 1977):

• Forming—As the group comes together, a period of uncertainty prevails as members try to find their place in the group and the group’s rules are worked out.

• Storming—Conflicts begin to arise as members confront and work out their differences.

• Norming—The group reaches some consensus regarding the structure and norms for the group.

• Performing—Group members become proficient at working together.

• Adjourning—The group disbands.

These stages are a fundamental part of organizational life and HRD. They help explain critical features of group dynamics and help practitioners work effectively with groups.

INDIVIDUAL THEORIES

Two groups of theories, adult development theory and career development theory, represent significant change theories at the individual level.

Adult Development Theory Adults do not grow up overnight—they undergo a developmental process. Researchers now understand that development does not end when adulthood is reached but instead continues to progress in various ways. Adult development theories have a profound influence on thinking about learning and change because adults’ learning behavior varies considerably due to developmental influences. It is unclear exactly how it changes—mainly because adult development theory is still mostly an array of untested models. This section provides only a brief overview of adult development theory. Readers seeking a more complete discussion of adult development should consult Knowles, Holton, and Swanson (1998), Bee (1996), Tennant and Pogson (1995), Knox (1986a), or Merriam and Caffarella (2006).

Overview of Adult Development Theories Adult development theories are generally divided into three types: physical changes, personality and life span role development, and cognitive or intellectual development (Merriam and Caffarella, 2006; Tennant, 1997). Role development theory’s primary contribution is to help explain how adults change in life roles. Cognitive development theories help explain key ways adults’ thinking changes over their life.

Bee (1996) characterizes development theories as varying along two dimensions. First, theories vary in whether they include defined stages or no stages. Stage theories imply fixed sequences of sequentially occurring stages over time. Stage theories are quite common, while others offer no such fixed sequence of events.

Second, some theories focus on development, while some focus on change during adult life. Change theories are merely descriptive of typical changes experienced by adults. There is no normative hierarchy intended, so one phase is not better than another. They merely seek to describe typical or expected changes. Many of the life-span role development theories fit into this category. The premise of these theories is that certain predictable types of changes occur throughout an adult’s life. Here are some examples of these:

• Levinson’s (1978, 1990) life stage theory, which divides adult life into three eras with alternating periods of stability and transitions. Each era brings with it certain predictable tasks, and each transition between eras certain predictable challenges.

• Erikson’s (1959) theory of identity development, which proposes that an adult’s identity develops through the resolution of eight crises or dilemmas.

• Loevinger’s (1976) ten-stage model of ego development progressing from infancy to adulthood.

The contribution of all life span theories to HRD is similar. First, they say that adult life is a series of stages and transitions, each of which pushes the adult into unfamiliar territory. Second, each transition to a new stage creates a motivation to learn.

Development theories imply a hierarchical ordering of developmental sequences, with higher levels being better than lower levels. They include a normative component, which suggests that adults should progress to higher levels of development. Many of the cognitive development theories fit into this category. The core premise of cognitive development theories is that changes occur in a person’s thinking processes over time. The foundation of most adult cognitive development theories is the work of Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget. Piaget hypothesized that children move through four stages of thinking: sensory motor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operations. Formal operations, at which a person reaches the ability to reason hypothetically and abstractly, is considered the stage at which mature adult thought begins—though many adults never reach it. Because Piaget was a child development specialist, his model implies that cognitive development stops upon reaching adulthood. Adult development theorists dispute that idea, focusing on various ways that cognitive development continues beyond formal operations.

Though few of the theories about adult development have been thoroughly tested, they have persisted because most adults intuitively recognize that change and growth continue throughout life. The implications of the adult development perspective for HRD are immense because adult learning is inextricably intertwined with adult development. We tend to agree with the prevailing thinking that there is no one theory that is “best.” Instead, adult development should be viewed as consisting of multiple pathways and multiple dimensions (Daloz, 1986; Merriam and Caffarella, 2006).

Career Development Theory While McLagan (1989b) defines career development as one of the three areas of practice for HRD (see chapter 2), in recent decades, it has had a declining influence within HRD. HRD has increasingly coalesced around personnel training and development and organization development as the primary fields of practice. Career development functions as an extension of the development component of T&D.

This shift in responsibility for career development is due to changes in the workplace, where the notion of long-term careers with single organizations is mostly gone. Individuals have taken control of their career development where organizations once had prevailed.

Career development has been slighted as a contributor to HRD. Career development theories about career choice among young people are less important to HRD because they do not fit traditional venues for HRD practice. However, career development theories that describe adult career development are vital contributors to HRD practice because they describe adult progression through work roles—a primary venue for HRD practice (see chapter 20). Fundamentally, these theories are a special type of change theory at the individual level. Two streams of research are beneficial to HRD: Super’s life span, life space approach to careers, and Dawis and Lofquist’s theory of work adjustment. Readers wishing more information on these theories are encouraged to consult Brown and Brooks (1996), Osipow and Fitzgerald (1996), Super and Sverko (1995), and Dawis and Lofquist (1984).

Super’s Life Span, Life Space Approach Super’s theory developed over a lifetime of research. Currently, the theory consists of fourteen basic propositions (Super et al., 1996). Because it is the most complex career development theory, many elements are included in the propositions. Fundamentally, it includes these basic components:

• Self-concept—Development through life is a process of defining, developing, and implementing one’s self-concept, which will change over time.

• Life space—A person’s life is composed of a constellation of work and nonwork roles, the balance of which changes over life.

• Life span—Life also consists of a macrostructure of developmental stages as described in adult development theory.

• Role changes in life—A person’s self-concept changes as life roles change, resulting in career changes as a person fits work to the changes in life roles and self-concept.

Unlike more traditional trait approaches to career choice and development, Super’s theory is focused on change. Super sees adult life as built upon change and development (the adult development perspective), which changes a person’s self-concept. A person’s work and career is, then, a place where the self-concept is acted out.

The power of this theory for HRD is that it directly explains many of the work-related changes adults undergo. A large portion of the demand for HRD in organizations is influenced by adults changing roles and acting out their changing needs at work. Furthermore, adults often turn to HRD to help them make career changes outlined in this theory. Thus, because this theory is change-oriented, it is a powerful career development theory for HRD.

Theory of Work Adjustment This theory is built on the process of individuals and organizations adjusting to fit each other (Dawis and Lofquist, 1984). According to this theory, individuals and organizations have needs, and they interact to meet these needs through the other. When the interaction is mutually satisfying, the person and environment are said to correspond with each other. Correspondence will mean that workers are satisfied, and they are satisfactory to the organization because they possess the necessary skills and expertise. This is called person–environment correspondence.

What makes this a change-oriented theory is that correspondence rarely lasts because the needs of the worker and the organization are constantly changing (Morris and Madsen, 2007). Thus, work and a career are an ongoing process of the organization and the worker providing feedback. Both may attempt to make changes to accommodate the other, called adjustment behaviors. A person’s perceptions of needed adjustments are influenced by their self-concept. This adjustment often takes the form of development as capabilities are expanded to meet organizational requirements.

Like most good theories, it is deceptively simple to describe but powerful in practice. It describes the fundamental systemic dynamics underlying much of the employee–organization interaction. Again, many of the adjustments made as a result of the interactions lead directly to HRD interventions. For example, changes in skills needed by the organization will result in developmental opportunities for employees. Similarly, changes in individual employee needs will often lead to HRD assistance for changing work roles. When combined with Super’s work, these theories provide valuable insights to change dynamics at the individual level in organizations.

Leading and Managing Organization Change

Of primary interest to the study of change has been the development of prescriptive process models to help change agents understand the best approach to leading change. These models provide specific tasks that change agents must accomplish to lead change successfully. Many different process models have developed, and while each has various nuances, at the core, most are quite similar.

Five key activities for contributing to effective change management have been proposed: motivating change, creating a vision, developing political support, managing the transition, and sustaining momentum (Cummings and Worley, 2001, 155). A more detailed eight-stage model for creating significant change is shown in figure 15.9.

Figure 15.9: Stages of Change Phases

Source: Kotter, 1996. Used with permission.

Conclusion

By understanding the complexities of change, HRD professionals can be more effective in organizations. The integration of learning, performance, and change under one umbrella discipline makes HRD unique and powerful. These three constructs are central to organizational effectiveness and will continue to become even more important in the future.

Reflection Questions

1. Why is change an important organizing construct for OD?

2. How can HRD become more of a change leader in organizations rather than a change facilitator?

3. What similarities and differences do you see among the organization, work process, group, and individual change theories?

4. Can all change theories be captured in one type or a combination of types within Van de Ven and Poole’s typology? Explain.

5. What is the responsible connection between change and performance?

Internet Resources. Instructional support materials for this chapter can be found on this website: www.texbookresources.net