77

STEP 1

NAME THE NEED

A man travels the world over

in search of what he needs

and returns home to find it.

George Moore

In 2005, disaster struck New Orleans. Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast and battered the Crescent City until there was practically nothing left. Flooding forced people to their roofs where they signaled to passing helicopters. Day after day, thousands of people cried out: Help!

Months before Katrina, a tsunami hit Indonesia killing thousands. Entire communities were destroyed. More than 212,000 people were swept away or killed by debris. Homes gone, infrastructure gone, and thousands of families torn apart.

Clearly, the victims of these catastrophes experienced grave fear, fear for their lives and for the lives of their loved ones. It’s not difficult to guess the immediate needs of the residents of New Orleans and Indonesia. None of us even needed to see the horrendous scenes on television, we knew instinctively what was required to help those poor souls: water, food, safety, and housing.

78

Thankfully, most of our crises are not so vast. They can be filled quickly and without the massive marshaling of troops and international support services. When it comes to asking for help, determining and defining the need are not so easily accomplished. The very nature of being in need keeps us in the dark and discourages us from exploring unknown pathways or novel approaches to fulfillment of our needs. Occasionally, what we think we need is not what we need at all.

Step 1: Name the Need

The very first step of the Mayday! process is focused on defining your need. When we feel the nervous angst of an unresolved problem, we want to eliminate that feeling almost immediately. We can’t wait to get it fixed fast enough. This is a natural first reaction. However, this step of the Mayday! process requires us to slow down and ask some questions. The intent is to get as clear about the need as possible and, at the same time, remain open to other possibilities. The following questions will move you toward clarity and openness.

What are your personal distress signals?

Sometimes when I don’t know I need help, others around me do know. They see me acting stressed and even out of control. Over time, I have learned to notice most of the warning signs, my personal distress signals. We all have them, and your friends, like mine, may perceive them before you do. These personal distress signals are designed to grab our attention and get us to acknowledge that we can’t do it on our own.

For example, you may notice an internal nervousness that resists being soothed. Maybe you have been more impatient than usual or perhaps your mood swings are fairly dramatic. Possibly, panic has found a way of creeping in at the start of your days, just before things get moving. Or maybe the anxiety captures you at night, just as you curl up in bed. Perhaps you experience crushing bouts of dissatisfaction with your current life and/or general pessimism about your future. You might even feel as though you are riding a giant pendulum, causing your emotions to swing from one side to the other.

79

Perhaps you’ve lost sleep because you wake up in the middle of the night, or you can’t drop off in the first place. Maybe your usual eating habits have changed for the worse. Did today’s lunch consist of microwaved popcorn noshed between appointments? You might have noticed a few more headaches. Perhaps, you can’t stop yawning—not because you are sleepy, but because you don’t seem to be able to get enough air. As for working out, forget it. And, of course, you don’t have to admit it to anyone, but maybe your libido just isn’t what it used to be.

There’s a chance too, that you seem to be whining more than usual. All you notice is what’s wrong, never what’s right. Maybe that’s something that your partner has pointed out—numerous times. The things that never used to bother you now send you into a rage. That voice in your head never gives you a break, as though its switch is stuck on auto-repeat. Perhaps too, you can’t seem to remember anything or keep your mind on the task in front of you. Maybe you’ve become so focused on the details you can’t see the big picture anymore, or vice versa.

Your body, mind, and emotions are trying to get your attention. These emotional, physical, and mental sensations are your personal distress signals—the warning signs that something is out of whack. With your mind on your problems, you might not see these signals at all—even if to others they seem like flashing strobe lights. These symptoms may have become such a regular part everyday of your life that they appear normal to you.

80

Do your shoulders feel tight, or your lower back knot up? Perhaps you are carrying too much of a load and you just need a little help with your burdens. Does your head hurt? Maybe you’ve been over-analyzing things; perhaps you need help finding time to play. Have you noticed that you’ve been grinding your teeth or that you regularly clamp your jaws shut? Perhaps you have wanted to tell someone something for a while and you need help getting the message across. The body doesn’t lie. We might be able to convince our minds and those around us that we’ll be all right, but the body knows better. It’s not going to let you get away with the overwork, the overstress, the doing it alone. Your body is going to send you signals until you do something about the help you need.

TRY THIS NOTICING YOUR OWN DISTRESS SIGNALS

Remember back to a time when you wanted to cry Mayday! What were the personal distress signals that let you know you needed help?

- What happened to your forehead when you were puzzling over a problem?

- What happened to your voice? Did it get higher pitched, lower, louder, softer?

- What happened to your jaw? Did it tighten or clamp down?

- What happened to your shoulders or upper back? Did they tighten up?

- What do you do with your hands? Did you shake them, bite your nails, drum your fingers, or crack your knuckles?

- What happened to the pace of your heart? Did it speed up or slow down?

- What happened to your breathing? Did it become shallow, deeper, slower, or faster?

- What happened to your overall posture? Did you slump over or stand tall?

- What happened to your eating habits? Did you eat more? Less?

- What happened to your exercise regimen? Did it increase or decrease?

- What happened to your relationships? Did they go through a “rough patch?”

81

“It will pass,” is a common phrase. Instead of seeing these behaviors and actions as indicators that something is wrong, we perceive them as annoyances or inconveniences. We are all smart enough to know that sometimes these symptoms won’t just “pass.” The body, mind, and emotions will return to balance only when we face our needs and deal with them.

What Is Your First Guess?

Once we notice our own personal distress, we instinctively take a guess at the best solution to our problem. This natural, almost instantaneous, reaction makes sense—we are thinkers. We live mostly in our heads. Our minds are rarely at rest, so they often go into overdrive when a need presents itself.

In business today, it’s common for a manager to warn her staff, “Don’t come to me with a problem unless you know how to solve it.” This admonition was originally created to lessen the burden on management and to encourage independent thought within the ranks of the workforce. On the one hand, the warning can be helpful. On the other hand, if a solution isn’t apparent, this same caution can send us spiraling toward the fear of shame. “How can I go to her with this problem? She’ll think I’m stupid for letting it happen and even more stupid because I don’t know how to solve it.”

82

Not only that, but when our distress signals are active, our thoughts are usually muddled because the riptide of fear is pulling for control. Fear does nothing to promote creativity of thought. Instead it crushes inspiration before it has a chance to start. Creative problem solving is best achieved when our heads are clear, when our bodies are calm, and when our emotions are optimistic. I don’t know about you, but when I’m struggling with an issue, the images in my mind blast through at a rapid pace. My body refuses to relax and my emotions head toward the dark side. In this state, I’ll never generate the ideas I need to release me from my dilemma.

Remember, fear, by its very nature, seeks to deceive. All fears try to convince us that the status quo is better than moving into the unknown. It doesn’t want us to see the possibilities that exist just beyond our sight. When we experience fear, no matter what kind, that list of possibilities is immediately restricted. We see only what fear wants us to see.

So before you ask for the help you need, remind yourself that your suggested resolution is only that, a suggestion. Your helpmate may have a much better idea.

Allan, a small business owner, was reeling from a market downturn. His revenues had dropped substantially, and he worried that he would have to begin laying off his employees. Over the years, Allan had created a support group of men and women who were also running their own small businesses. He knew they weren’t doing any better than he was. Each month, they would meet for breakfast and commiserate about the state of the economy. Each month, Allan would walk away feeling even more depressed and downhearted.

Allan came to me, asking me to help him find a way to invigorate his business. I answered, “It seems to me that what you need right now is a new support group, not a new business plan.”

83

Confused, Allan listened as I explained that his continued focus on what was missing in his business could be the real problem. Having an informal monthly pity-party wasn’t helping. It wasn’t much of a support group if he felt lousy afterward. Perhaps what he needed was a new set of voices and ideas. “Perhaps what you need every month is something or someone to inspire you to go back to your office with a better attitude and optimistic outlook.”

“That makes sense,” he replied. “If all I ever notice is what I don’t have, I won’t pay attention to any of the good things I do have.” Allan went back to his office determined to remain confident and upbeat. He found new people to listen to. He cut back on his breakfasts with the old crowd. It seemed to do the trick. His business rebounded well before anyone else’s on his “support” team.

Allan’s first guess at what he needed was a good one, but it wasn’t the right one. So deep in his need, Allan couldn’t see any other option than to change his business strategy. No matter how much he changed his strategy, his attitude would still have gotten in the way.

How many times have you confused what you want with what you need? How many times have you insisted that you knew exactly what had to happen in order for you to get your needs met? How many times have you subsequently realized that maybe what you thought you needed wasn’t really necessary? Your first solution is only one of many possibilities. Do not believe that because you came up with it, it is the only or the best solution.

Am I Attached to the Solution?

It is not unusual for us to become attached to our first guess. We decide that this solution is the one and only one that will get us the results we want. Insisting that we know what is best may be shortsighted and could limit our discovery of other creative solutions.

84

“Unattachment is the release of need or expectation associated with a specific outcome,” notes Cherie Carter-Scott in her book If Life Is a Game, These Are the Rules. “We become attached to the way we envision something working out, and struggle to make circumstances bend to our desires. Life, however, often has its own agenda, and we are destined to suffer unless we give up our attachment to things working out exactly as we would like.” If we truly need help, then we may be suffering already. Why add more anguish to the situation by forcing a conclusion?

Maggie and Colin were having troubles in their marriage. Maggie was sure they needed counseling, but Colin resisted it. Maggie just couldn’t let go of the idea that an experienced counselor would provide the help they needed to better understand each other. Colin, on the other hand, thought they could work it out themselves. The fears of surrender and shame nagged at him. He didn’t like the idea of involving an unfamiliar person in their marriage, and he certainly didn’t want anyone to think they couldn’t solve their own problems. Long arguments ensued over which solution was the best. They needed help.

One afternoon, while they were visiting Colin’s family, Maggie sat down with Colin’s mother. The two women got to talking about Colin and his particular style of communicating. Unbeknownst to Maggie, Colin was, at the same time, talking with his brother. Maggie and Colin were quiet on the ride home. Settling down for the evening, they slowly began to talk to each other. The insight they received from Colin’s mother and brother was enough to break the impasse they had created. Maggie realized that wisdom can arrive in very different forms, and Colin understood that an additional perspective can prove valuable.

85

Part of Maggie’s and Colin’s difficulty came from their attachment to their original choices for help. Maggie believed wholeheartedly that counseling was the way to go; Colin thought that they already had the tools they needed to resolve their differences. Neither was true.

Maggie and Colin missed seeing how their attachment to different resolutions was creating new problems. Those who answer your cry for help are capable adults accustomed to making decisions and living full and productive lives, just like you. They don’t need to be told what to do and they don’t usually respond well if you do. Now is not the appropriate time to remain resolute, especially when you are under the spell of the riptides. Respect your helpmate’s experience and strength. You’ll get more commitment and support if you remain open to new possibilities.

What Is the Gap?

As technical as it might sound, a gap analysis will also help you narrow down your specific need. A management tool used in many different disciplines including skill development and business assessment, gap analysis is simply a comparison of the current state with the desired future state. If our current situation is unacceptable, we assume that there is a better way, a better existence. The gap is that space between what is and what is better. That is the need that we seek help with.

Juan was an artist trapped in the body and life of a construction foreman. His dream was to spend his days working in his studio, watching the light fall on live models and painting until night arrived. But Juan also had responsibilities to his family and to his employer. He came to me seeking counsel because his boss had just offered him a promotion. Normally considered a good thing, Juan didn’t want this upgrade. “It will mean more time on the road, more time dealing with personnel issues, more time away from what I love doing,” he explained.

Juan had a need. A gap existed between what he wanted—a life of beauty and artistry—and what he had—a life devoted to contractors and blueprints. The question now, was how to close the gap?

We began by prioritizing the important elements of his life. Here is his list:

- My family

- My employer

- Me, my painting

Juan’s gap analysis clearly defined the current situation and his desired future state. With his three priorities, it became easy for the two of us to brainstorm a solution. At first, Juan was pretty sure he’d lose his job if he refused the promotion. After some discussion, he realized that was the fear of separation talking. He knew he was a great asset to the company and that his boss would be crazy to let him go. So Juan went to his boss and asked him for help keeping his life intact. He explained that the new role was not what he wanted. To soften the blow, Juan offered to find someone to fill the new position. “You should have seen his face when I said no to the promotion. But, then you should have seen mine afterward. I was so relieved.” Juan achieved his goal of supporting his family by continuing in his role as foreman. He may not have fully satisfied his employer, but Juan continued to be an effective site leader. This gave him time to continue to paint and to satisfy his need for creativity.

87

TRY THIS WHAT IS YOU RGAP?

- Describe the situation as you see it. What are problems this situation is causing you or about to cause you?

- Describe the ideal scenario. What would be different?

- What are your priorities?

- Now, record your first guess at how to best resolve your issue.

Do I Have a Need or a Want?

Now that you’ve explored the gap, ask yourself one more question: Is this what I need or what I want? The dictionaries provide a variety of definitions for both need and want, but here’s a good shorthand description: A need is something that you have to have, a want is something that you’d like to have. A need is a requirement, a want is an option. The definitions are simple to understand but not always so simple to apply.

Consider Juan’s situation. Some would read his story and think he had it all wrong. Choosing to paint instead of earning more money for his family sounds like Juan put his wants over his needs. For Juan, painting is a need. He wasn’t a dabbler. No, he felt a compulsion to pick up a brush every day. He was financially stable and his wife earned a good income. Money wasn’t the issue, satisfying his creativity was. For Juan, the choice was the right one.

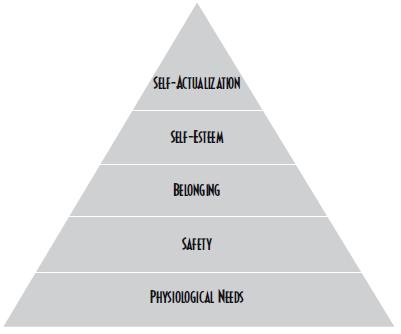

In working with Juan, we could have used Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. In the 1940s, noted psychologist Abraham Maslow identified a range of needs from the lowest, such as food, water, and breathing, to the highest level of personal self-actualization. Juan had achieved the basics: physiological needs, safety, love/belonging, and self-esteem. Now, it was time for him to focus on self-actualization.

88

HIERARCHY OF NEEDS

Abraham Maslow, 1943

“A Theory of Human Motivation”

TRY THIS IS IT A NEED OR A WANT?

As you consider the gap, distinguish between need and want. Spend time thinking about this, not just reacting to the itch to resolve it. Ask yourself:

- Have I taken care of other more urgent needs? (Those at the bottom of the model.)

- Is the help I seek necessary for me and my loved ones to be healthy and safe?

- How long could I go without it?

- Will having it make me feel better about myself?

- Can I achieve that another way?

- What are the consequences of not getting this need resolved?

- How will those consequences affect me and those I love?

If you suspect that the help you seek is “nice to have,” then treat it that way. Ask for help in satisfying it, and at the same time, understand that your want is ultimately less important than your need. Do your best to avoid behaving as though fulfillment of your desire is critical. Those who answer your mayday calls will want to know whether they are working toward fulfilling a requirement or an option.

We can be so hard on ourselves. What if we gave ourselves permission not to know how to solve everything? If it were that easy to think our way out of problems, don’t you think we would have already? What if we remained open to other suggestions, other ways of meeting our needs? The burden would shift from one set of shoulders to at least two. Go ahead and take a guess, but remember, it is only a guess.