SEVEN

Can Relevance and Rigor Coexist?

THE DEBATE ABOUT RELEVANCE and rigor in research is a favorite topic for academics. For as long as I can remember, this debate has been vigorous but inconclusive. This discussion is not limited to the focus of academic research and methodological preferences but also about the way the results of our research are communicated. Many practitioners find the language of academic journals overly (and often unnecessarily) complicated. Further, there is seldom an action bias in academic research. The next steps, for example, What can a manager do with these conclusions? How can she operationalize the results of academic research? have often remained unanswered. I have, over the past 25 years, avoided this debate about rigor and relevance. Early in my research career I made a clear choice: My primary audience was practitioners. My research, as a result, was focused on what I felt was relevant to managers and I chose outlets for my work that were practitioner oriented. Viewed from this perspective, I have been an academic “outlier.” I believe that was probably the reason that the organizers of this workshop invited me to write a chapter in this book. They asked me to reflect on my personal journey as a researcher.

The Research Focus

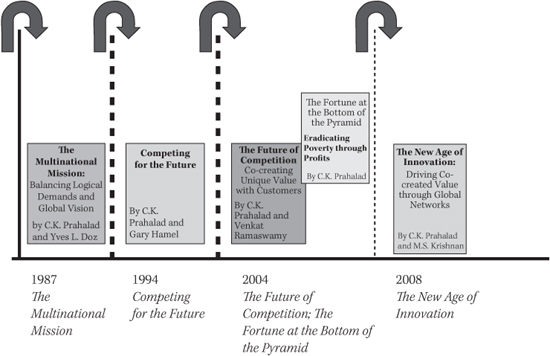

My research focus has evolved over time. Shown in Figure 7.1 are the major punctuations in my overall research journey starting with The Multinational Mission (1987) to The New Age of Innovation (2008). I call them punctuations as each of these books represents a milestone in my journey. Each book was preceded by a series of articles, mostly in managerially oriented publications. Most often, we also made a large number of presentations to managers in order to test and refine these concepts. These were intended to test the validity of the concepts with managers. This process represented a method for “review” of the usefulness of the research on a massive scale. Each book represented the culmination of a program of research as well as a vehicle for presenting both the findings and a distinct point of view.

FIGURE 7.1 Evolution of My Work

For example, in Multinational Mission, we argued that the tension between the need for global integration (GI) and local responsiveness (LR) is inherent in the nature of a global corporation. This framework has stood the test of time. Whether it is called “glocal,” or some other term, this tension is debated even today. Similarly, Competing for the Future developed a perspective on strategy as a process for resource accumulation and leverage, not just resource allocation. The concepts of strategic intent, core competence, core products and platforms, and strategic architecture are now part of the business vocabulary. But both these books were pre-Internet. So I embarked on the implications of the rapid spread of the Internet, which resulted in both The Future of Competition and The New Age of Innovation. As a result of these studies, we developed the concepts of personalized co-creation of value, the nodal firm, and innovation as being focused on one consumer experience at a time (N = 1), and resources for this effort to be marshaled from a large number of institutions—an innovation ecosystem (R = G). The book Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid was focused on building a framework to include 4 billion poor as micro consumers and producers in global commerce. This framework builds on the work on globalization, shaping markets of tomorrow, as well as co-creation and the use of technology solutions to serve the poor. The rapid commercial spread of cell phones around the world and the speed of diffusion of a modern technology among the bottom of the pyramid (BOP) markets has surprised even the optimists.

In this research effort, spread over 30 years, I have been singularly lucky with my research partners—Professors Yves Doz, Gary Hamel, Venkat Ramaswamy, and M. S. Krishnan. They added significantly to my understanding of the issues. We pushed ourselves very hard before we decided that it was time to write a book-length manuscript. This collaboration was a critical ingredient in building new concepts.

An Approach to Research

My approach to research always starts with the preoccupation of managers. Either they are catching up with their more successful competitors (“best practices”) or focusing on getting an edge over established competitors (“next practices”). I recognize that most of the managerial preoccupation is with benchmarking best practices. However, it does not take much effort to come to the conclusion that if firms only benchmarked each other, they would all look, think, and act alike. There can be no enduring competitive differentiation. At best, competitive advantage can only accrue from superior execution. So from the very beginning of my research career, I focused on next practices.1 Next practices allow managers to focus on gaining competitive advantage by being different. This distinction is critical. Managers seeking competitive advantage should focus not on being just “more efficient” (best practices) but on being “different” (next practices). A focus on next practices does not mean that efficiency and superior execution is to be ignored or undervalued. It just says that being different is a more defensible source of competitive advantage.

Research on next practices must start with what I call “weak signals.” Weak signals are about what is outside the normal industry practice. It is, for example, asking in 2000, the implications of Napster to the music industry. Napster showed that 14- to 16-year-olds loved the music but wanted to co-create their own albums. This was not an isolated phenomenon. More than 30 million were downloading music. They wanted to download one song at a time. They wanted music to be delivered and priced differently. It was a challenge to the traditional music industry. The questions to be asked were the following: What if we had amplified these signals? Could managers in the music industry have anticipated this shift? Why did Sony forgo the opportunity to do an “iPod?”

Research methods dictated by a focus on next practices and amplification of weak signals are very different from traditional research approaches. For example, a research bias toward next practices precludes the researcher from large-scale, longitudinal databases. By definition, next practice is not about the past; it is about the future and the likely discontinuities. Understanding weak signals is about looking for “outliers” who seem to defy current wisdom—Canon in imaging in the 1990s or Google in advertising in 2000.

Picking outliers does introduce sampling bias. It is based on the judgment of the researcher. I suggest that this bias may be less harmful than it appears at first sight as the “data itself” is often of less value than it appears. It is the extraction of the core principles that must stand the test, independent of the data from which they were derived. The goal is understanding the emerging “logic” of the industry and new business models. Therefore, the approach is to develop detailed understanding of the few outliers through case studies that extract the logical structure behind the new. The cases studies serve a single purpose—providing the raw material for extracting the logical structure. The data from the case are not about validating a hypothesis; it is about illustrating the concepts. The logical structure must have the explanatory power beyond the data that were used to extract it. The real test is in the following question: Does the theory stand on its own without the data set from which it was derived?

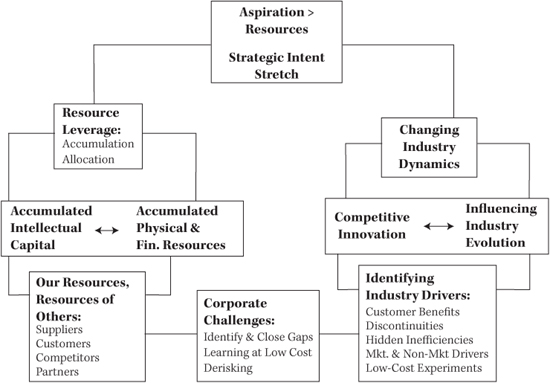

Let me illustrate what I mean by building a logical structure and using data as illustrations (see Fig. 7.2.). Let us use Competing for the Future as an example. We have to start with a single and intuitive premise:

Aspirations > Resources

This is the essence of entrepreneurship. No entrepreneur—Bill Gates (Microsoft), Sam Walton (Wal-Mart), or Murthy (Infosys)—starts with resources. They start with aspirations. This premise is self-evident. We called it “strategic intent” or “strategy as stretch.” This premise goes to the heart of the assumption in the strategy literature at that time, where the dominant thesis was “fit” (fit between goals and company resources). We argued for a misfit by design. If we want the organization to behave in an entrepreneurial way, we had to create these goals that exceeded available resources. In a start-up, this is easy. But in an established firm, we have to build a process for creating a shared aspiration. If you grant that self-evident premise, then the rest of the book flows logically.

FIGURE 7.2 Structure: Competing for the Future

There are only two broad approaches to managing the misfit between aspiration and resources: (1) Accumulate and leverage resources rapidly, and (2) change industry rules such that you can have an advantage over incumbents. On the first point, we came to the conclusion that the accumulated intellectual capital (core competence) in a firm is as much a resource as its financial resources. Competence can be accumulated and leveraged. Once we recognized this, the evidence was and still is overwhelming.

On the second point, we came to a similar conclusion: that firms could change the rules of engagement. We call them new business models these days. Previously, we called them competitive innovations. We also identified that the ability to create and shape your own future (through a strategic architecture) was of great importance in changing the rules of the game. These two processes effectively reduce the risk and investment. Re-using core competencies and core products (an embodiment of core competencies) reduces both risk and investment needs. It reduces the time for new product introductions or new business creation.

Similarly, changing the industry rules allows you to reduce competitive intensity and reaction from the incumbents who are defending their established positions. It also reduces risk, investment, and time. So “derisking big opportunities” was a key theme. All the examples were illustrations of these core ideas. The validity rests on the logical structure that was extracted from field research.

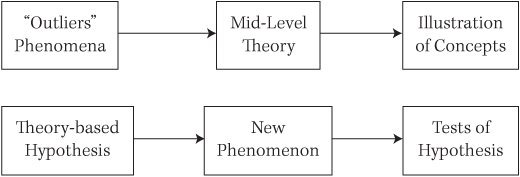

FIGURE 7.3 Research Approaches

The critical element of the research approach is that the process starts with the phenomena. It is the understanding of the outliers that allows us to construct a “mid-level theory,” a map that allows managers to understand the emerging competitive landscape and navigate it. We go back to the phenomenon to illustrate the concepts. This process is very different from starting with a theory and looking at the phenomenon, as shown in Figure 7.3.

I believe it biases research when we try to fit an existing theory to a new phenomenon, which may or may not be well explained by current theory. For example, there was a deeply held belief that relative market share is a source of competitive advantage during the 1980s and 1990s. If we started with this perspective, then we would have dismissed Canon, Toyota, Honda, CNN, Microsoft, and Dell as irrelevant to Xerox, GM, NBC, and IBM. They were too small and different. We need to ask ourselves whether starting with a “theory-based hypothesis” is appropriate if our goal is to understand “next practices.” The traditional approach can help us understand best practices well. But by definition, it is hard to generate a large data set when one is examining “weak signals.”

Identifying Big Issues

I recognize that some may be skeptical about finding big issues that warrant a multiyear research program. I am not, as we have plenty of new problems to wrestle with. I find using the following criteria useful in unearthing big issues. The questions that follow are fairly straightforward:

How Do We Pick a Next Practice Issue?

1. Is it a big, widely recognized problem?

2. Will it affect a wide range of businesses?

3. Is there opportunity to leap frog?

4. Are there established leaders? If not, can this provide a new source of advantage?

5. Will it change the economics of the industry?

6. Is there scope for radical innovations?

7. Can this be a big opportunity for innovators?

For example, these questions reveal that emerging areas such as “sustainability” will be an integral part of the way we run businesses. Should managers look at sustainability as a regulation and a compliance issue? Is sustainability about additional costs? Can sustainability become a source of breakthrough innovations? The issue of sustainability becomes more interesting (and urgent) when you combine the need for inclusive development—adding an additional 4 billion micro consumers and micro producers—to the global economy (BOP). What additional pressures should we expect to put on the sustainability equation? Seen this way, the debate about sustainability is intimately intertwined with poverty and poverty alleviation.

This problem presents a new challenge that will not go away. No business can ignore this pressure. Without adequate water resources (both quality and quantity), many businesses will find it hard to sustain themselves; be it beverages, food, or detergents. The foregoing examination of “sustainability” is just one example of how we can identify problems that will be around for quite a long time and on which very little systematic research is done from a managerial perspective. There is voluminous research in these areas centered around public policy issues but not enough to illustrate the criticality of these issues to managers. Further, these are not seen as opportunities for breakthrough innovations.

What Kind of Impact?

It is but natural to ask what kind of impact this approach is likely to have. The managerial impact is not difficult to discern. I believe that the research stream that I have been involved in has had its share of impact on managerial practice. The question is: Can it influence academic research or is it condemned to stay outside the academic orbit? One of my colleagues and chair of the strategy group at my school did a social science citation index (SSCI) analysis of my work for the period 1995 to 2009, a period of 15 years. He found that the overall citations were around 4,684 (about 300+/year). He also identified more than 10 papers and books that each had more than 100 citations. Finally, the citations came not just from management and business articles but also from as distinctly different fields as information technology, computer science, and forestry. He thinks that this combination—sheer volume of citations, the period over which they have been referred to, the number of papers and books that exceed 100 citations each, and the range of disciplines in which the work has had some impact—is unusual. I will let the readers be the judge.

A Word of Caution

A word of caution is in order. This approach to research is not for everyone. It is risky. Given the current academic environment that primarily values traditional, empirical work and publications in specified academic journals (A journals), this approach can be seen as “less sophisticated” and not meeting the standards of scholarship. It was less of a problem 25 years ago. The convergence of research methods to a dominant preference was just starting to take shape then. Now it is well crystallized, not only in the academic culture in the United States but increasingly in the European academic culture as well. There is, however, room for “outliers.” The fact that there is a dominant research approach and at the same time dissatisfaction with the outcomes of that approach, especially its impact on managerial practice, gives one hope.

On a personal note, I have had a lot of fun. My research has informed my teaching. It has resulted in many consulting arrangements with the chief executive officers (CEOs) of the world’s largest firms. Most important, it has helped me work with some of the best minds in the business—my coauthors. I could not have imagined or asked for a more fun-filled and productive career.

REFERENCES

Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C.K. (1994). Competing for the Future. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Prahalad, C. K. (2004). The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty through Profits. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Wharton School of Publishing.

Prahalad, C. K., & Doz, Y. L. (1987). The Multinational Mission: Balancing Local Demands and Global Vision. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Prahalad, C. K., & Krishnan, M. S. (2008). The New Age of Innovation: Driving Co-created Value through Global Networks. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). The Future of Competition: Co-creating Unique Value with Customers. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

C. K. Prahalad was Distinguished Professor, Ross School of Business, University of Michigan. A renowned management thought leader, Dr. Prahalad contributed to the development of fundamental business concepts including strategic intent, dominant logic, core competence, and co-creation. He will always be remembered for leading thinking with respect to bottom of the pyramid markets. He is the co-author of multiple best-selling business books including The Multinational Mission (with Yves Doz), Competing for the Future (with Gary Hamel), The Future of Competition (with Venkat Ramaswamy), and The New Age of Innovation (with M. S. Krishnan). His groundbreaking paper, The Core Competence of the Corporation (with Gary Hamel), remains the most reprinted article in the history of the Harvard Business Review. His articles in the Harvard Business Review have won a total of four McKinsey prizes.