6

Communicating sustainability with impact

Hertz promised to get you out of airports faster. Tide guaranteed to get clothes whiter than white. Keds sneakers assured kids that they would run faster and jump higher. But with environmentalism now a core societal value, consumers want to see green themes in marketing messages in addition to traditional promises associated with a better life. Indeed, communicating environmental and social initiatives with authenticity and impact can help establish one’s brand in the vanguard of this important trend. Indeed, such messaging can even ward off legislative threats and potentially protect one’s corporate reputation when things go wrong. Also, with stakeholders of all types – employees, investors, and consumers among them – wanting to know about the sustainability of products at every phase of their life-cycles, communicating the environmental and social advantages of one’s brands is now critical to running a well-managed business.

Although there are many opportunities associated with communicating one’s sustainability initiatives, challenges abound – and not communicating one’s environmentally and socially oriented product and corporate initiatives may be riskier still. Marketers who don’t tout the sustainability achievements of their brands may find that consumers and other stakeholders assume their products and processes are not ecologically sound; this is a sure way to be replaced on the shelf by a competitor with recognized green credentials! Fail to get on the radar screens of the sustainability-aware and lose opportunities to increase market share among the growing number of influential and affluent LOHAS consumers. Address the new rules of green marketing and expect to enjoy such rewards as enhanced brand equity and a stronger emotional bond with stakeholders.

Challenges of communicating sustainability

Convinced that you need to communicate the sustainable advantages of your brand? Not sure where to begin? Begin your planning process by considering the challenges. For starters, environmental and social benefits can be indirect, intangible, or even insignificant to the consumer. Consumers can’t see the emissions being reduced at the power plant when they use energy-saving appliances. (They may not even immediately notice the savings on their power bill.) Similarly, they can’t see the capacity increase in the landfill when they recycle, and they have to take it on faith that you pay a fair (living) wage to your employees (and your suppliers are doing likewise).

Trade-offs are a factor, too. Although many greener products are cheaper, faster, or more convenient, some are more expensive, slower, or not as attractive. Toilet paper made from 100% recycled content may be cheaper, but it may not be as soft as virgin counterparts. Taking the bus or train or carpooling saves money over driving one’s car and allows one to read, socialize, work, or snooze, but these ecologically preferable options fall short on the flexibility demanded by working parents who have to pick up the kids, a take-out dinner, and the dry-cleaning along a circuitous commute home.

Getting your sustainability-oriented campaign in front of the right people can be a challenge. Demographics-based markets such as homeowners living in the parched Southwest or new mothers with extra pennies to spend on organically grown baby food are easy to pinpoint through conventional media, but lifestyle-based targets such as wildlife lovers or the chemically sensitive, while being easier to reach these days thanks to the Internet, are still pretty hard to pin down.

Sustainable branding is complex – and can be pricey to do well. In addition to underscoring consumer benefits, the historical focus of marketing communications, today’s green consumers must be educated on the benefits of new, often technically sophisticated materials, technologies, and designs. New brand names must be established. Corporate green credentials must be put forth. Such tasks can overwhelm the budgets of start-ups with big green ideas. Compounding these tasks, sought-after benefits change with the times. In the past, organic produce was favored because of its perceived health benefits, but today, a wider audience scoops it up because they think it tastes better. Some homeowners install rooftop solar panels to keep up with the technologically savvy neighbors, while others simply want to save money on their energy bill.

And then there’s the question of credibility. As discussed in Chapter 2, industry is found to be far less trustworthy on environmental matters than other groups such as NGOs or government. As discussed further in Chapter 7, myriad eco-labels exist, but products are often expensive to certify to, and it is difficult to wade through the clutter. Get it wrong and a backlash can occur. Green communications that appear insignificant or insincere often invite criticism from environmentalists, bloggers, and citizen journalists who are quick to sniff out perceived “greenwashers”; and U.S. state attorneys general and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), as well as counterpart organizations in such countries as the UK (Advertising Standards Authority), Canada (Advertising Standards Canada), and Australia (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission), can be quick to take action against marketers who make deceptive environmental claims.

Finally, consumers can tire of the same green messages and imagery. Planets, babies, and daisies eventually wear thin with skeptical consumers. “Green fatigue” is brewing due to the plethora of green campaigns in so many consumer media. How many messages have you seen asking you to “do it for Mother Earth” or because “your kids will thank you for it”?

Ottman’s fundamentals of good green marketing

Sustainability-oriented marketing communications targeted to mainstream consumers work best when they address the new rules of green marketing head on. As alluded to in Chapter 2, if you want to communicate green benefits to consumers, you should keep in mind that the following conditions, fundamental to all green marketing efforts, must be met:

• Consumers are aware of and concerned about the issues your product or service professes to address.

• The consumer feels, as one person or in concert with others, that he or she can make a difference by using your product or service. This is “empowerment” and it lies at the heart of green marketing. (If consumers didn’t feel they would make a difference by using a greener product, they wouldn’t buy it in the first place.) This assumes that the sustainability benefits of a product or service can be clearly communicated.

• The product provides tangible, direct benefits to a meaningful number of consumers. In other words, green can’t be the only (or even main) benefit a more sustainable product provides. Consumers still need to be attracted to your product or service for the primary reasons why they would buy any product in that category, e.g., getting clothes clean, providing dependable transportation.

• Your product performs equally well or better than your competitors’ green or still “brown” alternative. Consumers will not give up quality or performance in order to secure a greener product. Said another way, greener products must perform their intended function first; environmental benefits are viewed as a new source of added value. What’s more, often the environmental benefits actually enhance a product’s ability to perform its intended function, and, as described more fully in Chapter 1, in these instances, marketers can expect to earn a premium! For example, organic produce tastes better, and Samsung’s new solar-power cell phone provides the important benefits of protecting one from running out of battery power.

• Premium pricing needs to be justified through superior performance or another benefit. Keep in mind that many consumers can’t afford premiums for many products, including green ones, especially in times of austerity.

• Consumers believe you. This means that your sustainability-related claims can be backed up by data or other evidence. Product-related efforts are reinforced by substantive corporate progress.

• Your products are accessible. To succeed with mainstream consumers, greener products must be available on the websites or shelves at popular supermarkets and mass merchandisers, right next to the “browner” products they are designed to replace.

Ottman’s fundamentals of good green marketing

Consumers must:

• Be aware of and concerned about the issues

• Feel empowered to act

• Must know what’s in it for them

• Afford any premiums – and feel they are worth it

• Believe you

• Find your brand easily

Source: J. Ottman Consulting, Inc.

Once you’re fully aware of these fundamentals, take advantage of the following strategies being forged by sustainability leaders around the globe to overcome the challenges and take advantage of the many opportunities afforded by green communications.

Six strategies of sustainable marketing communication

Six strategies of sustainable marketing communication

1. Know your customer

2. Appeal to consumers’ self-interest

3. Educate and empower

4. Reassure on performance

5. Engage the community

6. Be credible

Source: J. Ottman Consulting, Inc.

1 Know your customer

In selecting the right consumer to target, keep in mind the complexity of green consumer segments. As described in detail in Chapter 2, consumers can be segmented psychographically into the five NMI segments: LOHAS, Naturalites, Drifters, Conventionals, and Unconcerneds. They can be further segmented according to specific area of personal interest: natural resource conservation, health, animals, and the outdoors.

Just as there are many different types of green consumers, there are many different kinds of environmental and social issues of concern. Figure 1.1 on page 3 showed that water quality, hazardous waste, and pollution from cars and trucks top the list, but there are literally dozens of other issues ranging from endangered species to graffiti and noise pollution that concern even the most mainstream of consumers. Not all consumers will likely be aware of or concerned about all sustainability-related issues, so it is important to pinpoint the consumers who will be most receptive to your message, and to provide any additional education that’s needed to bring consumers on board.

One marketer who learned the hard way about the need to measure consumer awareness for the issues that affected their business is Whirlpool. In the early 1990s they won a $30 million “Golden Carrot” award that was put up by the U.S. Department of Energy and a consortium of electrical utilities for being first to market with a chlorofluorocarbon (CFC)-free refrigerator. But they misjudged consumers’ willingness to pay a 10% premium for a product with an environmental benefit that many did not appreciate. Likely many consumers, not even knowing what a CFC was, thought the appliance to be deficient, suggesting the need to educate consumers as part of one’s marketing; many examples are provided throughout this chapter.

2 Appeal to consumers’ self-interest

Many readers will approach this chapter thinking the focus will be on the best ways to highlight the ecological benefits of one’s products. You may have visions of ads showcasing the now tiresome images of babies, daisies, and planets that are associated so strongly with green ads. Although the environment is important to consumers – indeed, it may have been the primary reason the product was created in the first place – they will likely not be the primary motivation to buy your brand in preference to that of your competitors. In other words, don’t commit the fatal sin of green marketing myopia! As my colleagues, Ed Stafford and Cathy Hartman of the Huntsman Business School of Utah State, and I point out in our much-quoted article, “Avoiding Green Marketing Myopia,”1 remember that consumers buy products to meet basic needs – not altruism. When they enter a grocery, they don their consumer caps – looking to find the products that will get their clothes clean, that will taste great, or that will make themselves look attractive to others; environmental and social benefits are best positioned as an important plus that can help sway purchase decisions, particularly between two otherwise comparable products.

Keep in mind that with environmental issues a threat to health above all else, the number one reason why consumers buy greener products is not to “save the planet” (which isn’t in danger of going away anytime soon) but to protect their own health. So it is important to make sure that superior delivery of primary benefits are underscored in design and marketing. Focus too heavily on environmental benefits at the expense of primary benefits like saving money or getting the clothes clean – and expect your brand to wind up in the green graveyard, buried in good intentions.

Underscoring the primary reasons why consumers purchase your brand – sometimes referred to as “quiet green” – can broaden the appeal of your greener products and services way beyond the niche of deepest green consumers and help overcome a premium price hurdle. Demonstrate how consumers can protect their health, save money, or keep their home and community safe and clean. Show busy consumers how some environmentally inclined behaviors can save time and effort. To be clear, this does not mean focusing exclusively on such benefits – to do so would be to go back to conventional marketing altogether. Today’s consumers want to know your whole story, so focus on primary benefits in context of a full story that incorporates the environment as a desirable extra benefit; better yet, integrate relevant environmental and social benefits within your brand’s already established market positioning, and you’ve got the stuff for a meaningful sale.

Does your green product promise to protect or enhance health? You’re in luck. Categories most closely aligned with health are growing the fastest and tend to command the highest premiums. Consider a print ad for AFM Safecoat featuring 16 buckets of paint; 15 of the buckets are painted red and bear labels such as “Gorgeous Paints,” “100% Pure,” “Low Odor,” and “Sustainable.” However, the last bucket stands out in green and announces “The Only Paint that is Doctor Recommended.” While the ad highlights the health aspects of the low-VOC paint, the website delves more into the “eco” in Safe-coat, stating that it is “the leading provider of environmentally responsible, sustainable and non-polluting paints, stains, wood finishes, sealers and related green building products.”2

Does your product appeal to the style-conscious? American Apparel was created as a brand proud to be made in the United States, provides excellent working conditions for its employees, and uses organic cotton. But, in 2004, when its “sweatshop free” label did not bring in the numbers that CEO Dov Charney was hoping for, he switched to promoting a sexy, youthful image for his company – complete with racy, controversial ads featuring scantily clad girls. Three years later, the company has 180 stores and revenue around $380 million.3 (Sounds heretical? Keep in mind that the same sustainably responsible clothing is still being sold to consumers, together with all the same benefits to society and the environment; mainstream consumers simply need to hear a message that underscores the primary reason why they buy clothes in the first place.)

Does your product save consumers money? Ads for Kenmore’s HE5t steam washer state that it uses 77% less water and 81% less energy than older models. The headline grabs readers with the compelling promise, “You pay for the washer. It pays for the dryer.”

Is your product quieter, too? Television commercials for Bosch appliances spotlight energy efficiency and quiet performance. In one, a gentle deer walking through a forest meanders past an operating Bosch Nexxt washer and dryer tandem and never notices the appliance. A second ad highlights an owl swooping through an orange canyon to rest on the working Bosch Evolution dishwasher. Positive environmental impacts, obliquely referenced by situating the products in a forest setting and using animals, are tertiary to the silence and energy efficiency. Among its accolades is an Excellence in ENERGY STAR Promotion Award bestowed by the EPA.

When it comes to identifying the primary consumer benefits your greener alternatives can deliver, many brands like the ones described above find that their products’ green benefits neatly translate into something direct and meaningful to the customer; energy savings translating into cost savings is an excellent example. (See Fig. 1.5 on page 19 for more examples.) However, when direct consumer benefits are not readily apparent, green marketers can use what my colleagues Ed Stafford and Cathy Hartman have dubbed “bundling,” i.e., adding in desirable benefits.4 An excellent example is the award-winning and highly successful Whirlpool Duet, a front-loading washing machine and dryer that bundled a highly appealing design with energy and water savings. It may be safe to say by bundling design with the environmental benefits, Whirlpool was able to fetch a higher premium for their offering.

In choosing the combination of primary and sustainability benefits to communicate, strive to integrate the two in order to ensure relevance. As examples, greener benefits such as recycled content or energy saving can add fresh life to the messaging of value brands, as is the case with Elmwood Park, New Jersey-based Marcal’s Small Steps campaign which positions the use of 100%-recycled-content household paper products as an easy measure to take for the environment and save money. Our client, Austria-based Lenz-ing, makes Modal brand fiber from reconstituted cellulose from beech trees. The resulting fabrics are touted as “dreamy soft” by Eileen West in their legendary nightgowns heralded for quality and comfort. Forbo promises that its Marmoleum linoleum flooring “Creates better environments.” Synergies can come from surprising places; the cause marketing campaign mentioned later in this chapter for Dawn’s dishwashing liquid relating to Dawn’s role in cleaning oil-despoiled waterfowl acts as a subtle demonstration of the product’s efficacy.

Understanding the specific interests of your green consumers can also add relevance to marketing communications programs in other ways. For example, segmenting green consumers can enhance targeting and relevance. In planning your green marketing campaign, ask such questions about your consumers as: To which environmental organizations do members of our target audience belong (the Appalachian Mountain Club or Greenpeace)? Which types of vacations do they take (hiking or the beach)? Which environmental magazines and websites do they read or visit (Sierra or Animal Fair)? Which types of products do they buy? (green fashions or energy-sipping light bulbs)? Which eco-labels do they seek out (Renewable “e” Energy or Cruelty-free)?

3 Educate and empower consumers with solutions

Consumers want to line up their shopping choices with their green values, and they applaud marketers’ efforts to provide the information they need to make informed purchasing decisions as well as to use and dispose of the products responsibly. Especially effective are emotion-laden messages that help consumers acquire a sense of control over their lives and their world. For advertisers that make the effort to teach, educational messages represent special opportunities to boost purchase intent, enhance imagery, and bolster credibility. So demonstrate how environmentally superior products and services can help consumers safeguard their health, preserve the environment for their grandkids, or protect the outdoors for recreation and wildlife. Make environmental benefits tangible through compelling illustrations and statistics and make consumers feel as if their choices make a difference.

In 2008 Pepsi launched an empowering Have We Met Before? recycling campaign. It featured fun fact-based messages from the National Recycling Coalition that underscored the difference recycling can make, and it encouraged consumers to make recycling a part of their daily routine. Two facts emblazoned on specially designed cans included: “Recycling could save 95% of the energy used to make this can” and “The average person has the opportunity to recycle 25,000 cans in a lifetime.”5

Increasingly, consumers are turning to the Internet for information. Opportunities abound to provide additional information on one’s own website or a third party’s website, in addition to conventional places such as advertising and packaging. Yahoo!’s 18Seconds.org website, named for the time it takes a person to change a light bulb, ranks states and cities according to their CFL purchases and describes CFLs and the difference it makes to use them. Also included are facts about where energy comes from and opportunities to spread the word by emailing friends or linking to the page from one’s own website.6

Sensing an opportunity to home in on sales of the beleaguered bottled water industry, in 2007 Brita and Nalgene teamed up to co-promote their Brita filters and Nalgene water bottles as a cheaper and greener alternative to bottled water. A special website, www.filterforgood.com, described the carbon costs of producing and shipping bottled water as well as the environmental strain associated with plastic bottle waste. Visitors were invited to “take the pledge” to reduce bottled water usage. Displaying power in numbers, a map of all the pledges made across the country depicted how many bottles were saved.7 Appealing to the “online generation,” filterforgood.com also created a Facebook application that allows users to track how many bottles they have saved, and gives them a chance to win a $100 prize pack.8

Dramatize environmental benefits

Make your environmental achievements tangible and compelling to your target by citing statistics and using visuals that help dramatize the potential benefits. To help them reach their goal in 2007 of selling 100 million CFL light bulbs, Wal-Mart underscored the facts that, by changing out all the bulbs in an average home, customers could save up to $350 per year, and that the environmental savings represented the equivalent of taking 700,000 cars off the road or conserving the energy needed to power 450,000 single-family homes.

Similarly, Netflix markets its DVD-rental and video-streaming service on the convenience it provides; yet on its website it also points out that, if Netflix members had to drive to video rental stores, they would consume 800,000 gallons of gasoline and release more than 2.2 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions annually.9

Addressing |

HSBC empowers big change with its

There’s No Small Change campaign

HSBC, the global banking giant headquartered in the UK, has many reasons to be concerned about global climate change, principal among them its many office buildings and thousands of branches around the world that need to be lit, heated, cooled, and ventilated, as well as running the millions of computers, printers, copiers, and other office equipment they contain. For 20 years, the bank made steady, significant investments in what eventually became an industry-leading Carbon Management Plan which helped the company achieve carbon neutrality in 2006. In recognition of its efforts, HSBC won the EPA’s Climate Protection Award in 2007; and for two years straight, in 2005 and 2006, the EPA and U.S. Department of Energy named the company “Green Power Partner of the Year.”

With this strong track record of environmental achievement on an issue relevant to a broad swath of consumers, we thought HSBC was ready to make a powerful message: with 120 million customers worldwide, the bank could champion the power of small changes. Hence was born HSBC’s There’s No Small Change marketing campaign, which we had the pleasure to work on with them. Run in the U.S. during spring 2007, it gave consumers empowering tips for reducing their own carbon footprint through various steps including HSBC’s new paperless checking and statements.

Newspaper ads, in-branch posters, and other collateral developed by our partner, the New York office of JWT, the global advertising agency with support from my firm, J. Ottman Consulting, suggested ways customers could make a difference in all aspects of their lives: for instance, “get green power,” “reduce paper waste,” and “bank wisely.” Carbon calculators provided by a leading environmental group, handed out inside the branches and made available through a special website, helped customers measure savings from such actions as powering down computers and copiers at night. New customers were presented with “Green Living Kits” packed with such enviro-goodies as CFLs, a Chicobag reusable shopping bag, coupons for organic flowers, and a free issue of The Green Guide magazine. For every new account opened, HSBC donated money to local environmental charities, totaling $1 million by the end of the campaign. To extend reach to small business and “premier” customers, HSBC worked with local nonprofit groups to sponsor green business seminars, an Earth Day event in Central Park, New York, and a Green Drinks networking event.

Partnering with credible organizations was critical to the campaign strategy. In the words of JWT SVP Linda Lewi, “When we developed the creative platform for ‘There’s No Small Change’ we knew how the brand behaved as it executed the campaign would be as important as what it said, and so we developed a grassroots communications plan that partnered with green organizations to provide the everyday sustainable solutions and outreach efforts to our target consumers.”

By adopting a strategy focused on credible education and empowerment, HSBC energized its employees, earned credibility among its audience of green consumers and businesspeople, and built its business: the effort yielded 46,420 new accounts (103% of goal and for only 65% of the acquisition cost of a typical customer) – with a 50% uplift in online bill paying, higher deposit balances in both Personal and Premier accounts, with three times the standard cross-sell ratio (people who opened a checking account and bought another product).

To boot, I’m proud to report the campaign won one of the first ever Green Effie awards from the American Marketing Association, sponsored by Discovery Communications’ Planet Green network, honoring effective eco-marketing.10

Be optimistic

In the midst of a national energy crisis in 1978, U.S. president Jimmy Carter took to the airwaves in a cardigan sweater encouraging Americans to conserve energy by turning down the thermostat to 68°. His campaign failed because of its link to deprivation (and the cardigan sweater industry is still reeling from its effects). Like the entire “back to basics” green movement of which it was a part, President Carter’s well-intended initiative failed because it represented a threat to the upward mobility and prosperity that is America. While some may question the idea that “bigger is better” and “growth is necessary for a healthy economy,” most Americans have not historically been willing to reverse their hard-won struggles to “have” for a future characterized by “have not.”

Happily this mind-set is already changing for the better in some advanced environmentally aware countries such as Germany and in Scandinavia, and ideally will in the rest of the world. But for now businesses need to play by one of the fundamental new rules of green marketing: consumers believe that technology, coupled with cooperative efforts on the part of all key players in society, will safeguard their future. So, invite consumers’ participation via simple actions and the prospect of a better future – not by leveraging fear tactics, playing to pessimism, or pressing guilt buttons. That’s why we guided our client, Epson, towards an more hopeful, integrated corporate positioning, “Better Products for a Better Future,” and why TV commercials for Kashi cereals showcase vignettes of healthy people and end with the tagline, “Seven Whole Grains on a Mission.”

Londonderry, New Hampshire-based Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt and other popular dairy products, manages to keep its messages refreshingly upbeat and fun. A visit to their “Yogurt on a Mission”-themed website lets fans meet Gary Hirshberg, the “CE-Yo,” view lighthearted videos about how they make yogurt, even “Have-A-Cow” by learning about some of the specific family farms from where it sources its ingredients.11

Finally, offering the opportunity to “test drive a low-car and less expensive lifestyle,” the Zipcar car-sharing service, in June of 2009, playfully announced the “Low-Car Diet,” asking participants from all 13 Zipcar cities in the U.S., Canada, and England to swap their personal car for a Zipcar membership, supplemented by the use of bikes, public transportation, and walking. Positioning the program as a step up in lifestyle for participants, the company asserted that the “Monthlong program gives urban residents the opportunity to experience the economic, environmental and health benefits of a low-car lifestyle.”12

Address the underlying motivations of consumers

In line with the segmentations of green consumers outlined in Chapter 2, focus your messaging on concepts that are understood by the consumers who are most important to your business. Empower the disenfranchised. Reward those consumers who are trying to make a difference.

• Motivate the deep green LOHAS consumers by demonstrating how they can make a contribution. Reward their initiative, leadership, and commitment to high standards.

• Show Naturalites (and my Health Fanatics) that environmental benefits are consistent with healthy lifestyles. Demonstrate how natural products can benefit adults, children, and pets.

• Provide Drifters with easy, even fashionable ways to make a contribution that doesn’t cost a lot. Enlist the support of celebrities and help them show off their eco-consciousness on favorite social networking sites.

• Encourage Conventionals (and my Resource Conservers) with practical, cost-effective reasons for choosing greener products and behaviors. Underscore opportunities to save money immediately or over the lifetime of a product. Communicate how long a product may last, or that it is reusable.

• Help Unconcerneds understand how all individuals can make a difference. Underscore that small actions performed by many people can make big changes.

|

Addressing |

Toyota Prius appeals to mainstream consumers one segment at a time

On launching its Prius sedan in 2001, Toyota opted first to target not the green-leaning drivers one might expect, but rather tech-savvy, “early adopter” consumers. Featuring a beauty shot of a shiny new car parked at a stoplight and illustrated by the provocative headline, “Ever heard the sound a stoplight makes?” an introductory print ad emphasized the hybrid car’s quiet ride (and specifically the fact that the motor, switched into electric gear, did not idle at stop lights like combustion engines). Putting primary benefits first, the key visual was a big, bold beauty shot of the car itself set off against a backdrop of the Golden Gate Bridge while the body copy explained the revolutionary technology. Environmental benefits appeared at the top right corner of the ad – in mouseprint – in the form of compelling statistics about the car’s fuel economy and emissions. To establish its green bona fides and get a buzz going among influential greens, a supplemental campaign, “Genius,” spotlighted the car’s lighter environmental touch and activist group endorsements.

Spiked gasoline prices subsequently triggered a new campaign highlighting the car’s fuel efficiency, no doubt bringing price-conscious Conventionals on board. Today, its distinctive styling makes the Prius a rolling billboard of one’s environmental values and forward thinking. A successful public relations campaign, including stunts like celebrities rolling up to the Academy Awards in a Prius, bestow the car with a “coolness” factor – the reason why, anecdotally, many people buy a Prius.

The potential to motivate the large mass of passive greens with the promise of fitting in cannot be overstated. That’s because environmental issues are inherently social – your gas-guzzling car pollutes my air; my wastefulness clogs our landfill. Today, the “cool” people care about the environment – the influential LOHAS consumers whom many emulate and, of course, so many Hollywood celebrities. Intentionally, “cool” underpinned the most successful anti-litter campaign in history. It was created for the Texas Department of Transportation by our friends at the Austin-based GSD&M advertising agency in 1985 and is still running. When research showed that slogans like “Pitch In” were having no effect on habitual litterers (men 18–34), advertising enlisted popular Texas celebrities such as Willie Nelson, Lance Armstrong, and Jennifer Love Hewitt to demonstrate that it is “uncool” to litter.14 The Don’t Mess with Texas campaign has helped to significantly reduce visible roadside litter, from 1 billion pieces of trash tossed onto Texas roads in 2001 to 827 million pieces in 2005.15

4 Reassure on performance

Environmentally preferable technologies are new to consumers and often look or perform differently than their brown counterparts. Carried over from the days when CFLs sputtered and cast a green haze and when natural laundry detergents left clothes dingy, as pointed out in Figure 2.11 on page 40, “Barriers to green purchasing,” greener products are still perceived by some as less effective or not having the same value as the more familiar brown alternatives. And, although these perceptions are declining, it still deters some potential customers from purchasing greener products.16 Remove this potential barrier to purchase by addressing the issue head on.

Seventh Generation (see Chapter 4) brand dishwashing liquid, which competes with Palmolive and Dawn – brands with long-established track records for cutting grease – underscores its efficacy by stressing in print ads spotlighting an adorable youngster, “Because you don’t have to choose between safety and spotless dishes,” while Reynolds Wrap addresses the myth that recycled content is somehow inferior to virgin, by emphasizing its Reynolds Wrap 100% recycled aluminum foil is “100% Recycled, 100% Reynolds.”17

5 Engage the community

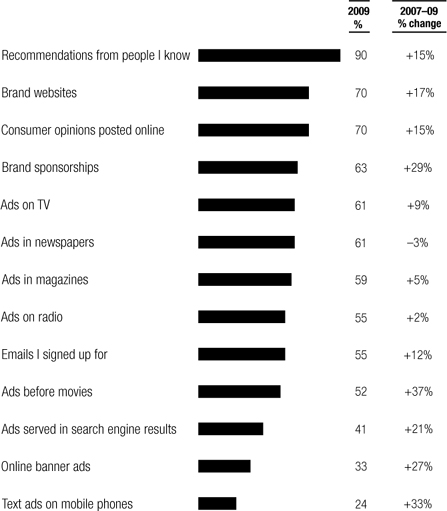

As underscored earlier in this book, green consumers tend to be well educated, and quite reliant on their own research. As demonstrated in Figure 6.2, they increasingly tend to trust the recommendations of friends and family even more than traditional forms of paid media; hence the astronomical rise in importance of social media in the past few years.

Figure 6.2 Whom do consumers trust for information?

Consumer trust in advertising by channel (trust somewhat/completely), 2009 compared to 2007

Source: The Nielsen Company, Trust in Advertising, October 2009

Reprinted with permission

This suggests rather than simply communicating green benefits in traditional ways, take the opportunity to use your brand to educate and engage your consumers about the issues they are concerned about: the values that guide their lives and purchasing. Acknowledge the consumer’s new role as co-creator of your brand and vigorously stoke the conversation. Offer credible, in-depth information and tell meaningful stories that extend beyond paid advertisements in broadcast and print, and on pack messages, to include sponsorships and information on websites and social media. Given consumers’ propensity to trust others like themselves, educate them on the details of your products and packaging and provide infrastructure and content that makes it easy for them to share information about your brand with each other.

Engage in cause-related marketing

Best known as promotional efforts in which businesses donate a portion of product revenues to popular nonprofit groups, cause-related marketing can enhance brand image while boosting sales, and allows businesses to have an impact that goes far beyond that associated with just writing a tax-deductible check (philanthropy). With cause-related marketing, everybody wins. Consumers can contribute to favorite sustainability causes with little or no added expense or inconvenience; nonprofit partners enjoy broadened publicity and the potential to attract new members and financial support; and business sponsors and their retailers and distributors can distinguish themselves in a cluttered marketplace, enhance brand equity, and build sales.

No longer viewed as a short-term promotional tactic, all signs point to cause-related marketing as a mature, long-term strategic business practice approached with increasing sophistication by organizations large and small. International Events Group (IEG) Sponsorship Report predicts that cause marketing will rise by 6.1% to $1.61 billion in 2010, up from $1.51 billion in 2009.19

Confirming that cause-related marketing represents the power to build one’s business, the 2008 Cone Cause Evolution Study revealed record high levels of positive response from consumers to cause-related campaigns, specifically:

• 85% of Americans say they have a more positive image of a product or company when it supports a cause they care about (remains unchanged from 1993)

• 85% feel it is acceptable for companies to involve a cause in their marketing (compared to 66% in 1993)

• 79% say they would be likely to switch from one brand to another, when price and quality are about equal, if the other brand is associated with a good cause (compared to 66% in 1993)

• 38% have bought a product associated with a cause in the last 12 months (compared to 20% in 1993).20

Cause-marketing campaigns conducted by organizations worldwide span a range of environmental and social topics. One of the most visible in the history of cause-related marketing is Project (RED). Launched in 2006 by Bono of rock group U2 and Bobby Shriver of Debt, AIDS, Trade in Africa (DATA), multiple high-profile partners including American Express, Apple, Converse, Dell, Gap, Giorgio Armani, Hallmark, Motorola, and Starbucks raise money for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund) by donating 50% of profits from products labeled as (RED). Funds generated to date have provided more than 825,000 HIV-positive people with a year’s worth of antiretroviral therapy, provided 3.2 million AIDS orphans with basic care, and supported programs that have prevented more than 3.5 millions deaths.21

IKEA partnered with UNICEF on a promotion to benefit children in Angola and Uganda. IKEA agreed to donate $2.00 from every sale of their BRUM teddy bears to UNICEF’s “Children’s Right to Play” program, which uses play-based interaction to educate and empower children in need. The promotion was called “A Bear that Gives,” and between 2003 and 2005 it raised $2.2 million, which went to the education of 80,000 street children in Angola and 55,000 children in displacement camps in Uganda, put 38,000 Ugandan children in daycare centers and reunited 200 of them with their families.22

Opportunities exist for even small businesses to get meaningfully involved in cause-marketing. Consider 1% for the Planet, founded by the environmentally passionate Yvon Chouinard (founder of Patagonia) and Craig Mathews (owner of Blue Ribbon Flies) to connect businesses and their consumers with philanthropy. Currently, more than 700 environmentally conscious companies contribute 1% of their sales to a growing list of more than 1,500 environmental groups around the world.23 Participating organizations, ranging from Galaxy Granola in California and our client, Modo, makers of E(arth) C(onscious) O(ptics) eyewear in New York, to Natural Technology in France, benefit from the marketing boost that accrues from being listed on the 1% for the Planet website and the ability to differentiate their businesses from their competition by using the 1% for the Planet logo on their packages and promotions.

Lastly, and perhaps with important implications for the future, some brands have made causes central to their business. Consider the enormously successful Newman’s Own brand, which through the Newman’s Own Foundation donates all profits to charitable causes, and TOMS One for One campaign which gives a pair of shoes to a child in need for every pair of their rubber-soled alpargatas shoes they sell.

Before embarking on your own cause-marketing effort, realize that there are some rules of the road. Consumers are attracted to causes that put them in the driver’s seat, and they will turn on a misguided campaign. Examples abound. Some Sierra Club members created a stir – and some even pulled out of the organization – in response to breaking news that the Sierra Club was receiving an undisclosed amount of money for what they perceived as an endorsement of Clorox’s Green Works cleaning products. Sierra Club members’ objections to the partnership included the fact that Clorox manufactured chlorine and that 98% of Clorox products were still made from synthetic chemicals. (Green Works only accounted for 2% of Clorox’s total sales).24 Both organizations now disclose the financial compensation that Sierra Club receives for its support, and, likely prompted more by pending legislation than by the Sierra Club, as of late 2009, Clorox announced it would no longer make bleach out of chlorine and sodium hydroxide.25

Reflecting its ability to gently but effectively clean waterfowl affected by oil spills, Dawn dishwashing liquid is running a cause-related campaign with the Marine Mammal Center and the International Bird Rescue Research Center in which it will donate $1 for every specially marked package bought by consumers. However, some visitors to its Facebook page and YouTube commercial have protested at the promotion, citing that Procter & Gamble tests its products on animals, forcing the company to defend its policies and remind its detractors that it has invested more than $250 million developing alternative testing methods.26

Finally, Ethos Water, co-owned by Pepsi and Starbucks, donates 5 cents for every unit sold to help people in underdeveloped regions to get clean water. Environmentalists question this approach, maintaining that clean, drinkable water should be a human right and not a function of corporate profits. They also maintain that promoting bottled water for environmental benefits is inconsistent with the related impacts of plastic recycling, energy expended to transport the product, and potential depletion of natural water supplies.27

To reap the benefits amply demonstrated over 15 years of cause-related marketing, follow these guidelines for success suggested by Cone’s 2008 Cause Evolution Study:28

• Allow consumers to select their own cause

• Ensure that the cause you pick is both personally relevant to consumers and makes strategic sense to your business

• Choose a trusted, established not-for-profit organization

• Provide practical incentives for involvement, such as saving money or time

• Provide emotional incentives for involvement, such as it making them feel good or alleviating shopping guilt.

Get creative

Many sustainable brand leaders including Whole Foods, Seventh Generation, Ben & Jerry’s Homemade, Burt’s Bees, and Stonyfield Farm, have built their reputations and continue to establish goodwill credibly and affordably through such creative publicity-generating efforts as sponsoring worthy causes, adopting local charities, protecting small dairy farmers, or donating profits to charity. They have spoken out against bovine growth hormone (in the case of Ben & Jerry’s and Stonyfield Farm) or supported organic and fair trade products, organizing special events targeted at younger demographics such as Ben & Jerry’s One World One Heart music festival, or Burt’s Bees’ Beautify Your World tour, allowing consumers to try products first-hand.

With the mainstreaming of green, larger companies are starting to get creative, too. In 2007, Philips, for example, partnered with the Alliance for Climate Protection and the global Live Earth concerts to promote the use of energy-efficient lighting via their A Simple Switch campaign to combat climate change.29 Companies such as Sprint and Coca-Cola’s Odwalla brand are sponsoring signs and trail maps at parks and ski resorts, a very direct way to reach outdoor enthusiasts.30

Without paid media advertising how did Stonyfield Farm become the third largest yogurt brand in the U.S.? The answer is its unconventional marketing, most of it on the pack – what founder Gary Hirshberg calls “mini billboards.” Packaging and lids highlight Stonyfield Farm’s environmental practices and the environmental and social causes it supports, in addition to facts that educate consumers about the benefits of adopting a sustainable lifestyle. The company even offers a “Have-a-Cow” program where consumers sponsor a dairy cow, thus bringing them closer to the farmers providing the yogurt they eat.31

With nearly 2 billion users worldwide – more than a quarter of the population – the Internet represents an efficient means of reaching consumers with information and advice on greener products.32 Spending on online and mobile advertising, including search and lead generation, online classifieds, and consumer-generated ads, reached almost $30 billion in 2007, up 29% from the year before.33

Many environmental groups have created websites in order to share information on global environmental problems, and a few sites now have microsites where consumers can shop and/or obtain information about greener products, companies, and behavior. Some good examples include GreenHome.com and Buygreen.com.

Sustainability leaders are now devising creative ways to get closer to their consumers and generate a positive buzz about their brands via blogging and social networking sites and by creating communities through their own websites. For example, Yahoo, GM, Crest, and Eden Organic are just a few of the brands that advertise to the seven million members of the Care2.com social networking site. No Sweat Apparel uses online blogs and sponsorship to create a buzz about their clothing, which is produced in factories throughout the world where all workers are paid a living wage.34 Consumers know that greener products and services are still relatively rare, and when they find an exciting new brand which is also sustainable, they will likely tell their friends about it, sometimes with support from the brand itself. Consumers can “friend” Method on Facebook to learn about new product offerings and leave positive testimonials, and thousands of fans of the “Seventh Generation Nation” network Facebook page leave feedback and even suggest new product ideas.

Out of the 110 million Americans (making up 60% of Internet users) who use social networking sites such as Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, or MySpace, 52% have “friended” or become a fan of at least one brand on a social networking site.35 One of the biggest users of such social networking sites is Whole Foods Market. To help celebrate their one millionth Twitter follower, Whole Foods held a contest that asked followers to tweet their food philosophies in five words. The ten most creative tweets received a $50 Whole Foods gift card.36 To engage their Facebook followers in conversation, throughout the summer of 2010, Whole Foods invited them to share some of their fondest high school tunes, how hot it was where lived, and their favorite party recipes.37 It’s time to plan for their next millionth addition; as of August 2010, Whole Foods had 1,792,404 followers on Twitter in addition to 310,638 Face-book fans.

The web and social media are creating opportunities for exciting new forms of experiential marketing including YouTube videos, product placement, mobile advertising, iPhone and BlackBerry applications, and pop-up stores – all just beginning to be explored.

Addressing |

Tide Coldwater warms up consumers with engaging website

Procter & Gamble’s Tide Coldwater is specially designed to clean clothes in cold water as effectively as the leading competitive detergent does in warm water. Tide Coldwater is a concentrated formula (reducing packaging as well as energy costs) that may save consumers up to 80% of the energy they would use per load in a traditional warm/cold cycle of a hot water top-loading machine.

To assuage doubters, P&G assures customers that its cold-water formula works just as well as traditional products to wash clothes. With both a regular and high-efficiency (HE) formula, it also works with all washing machines and traditional laundry additives such as bleach and fabric softeners.

In 2005, P&G launched Tide Coldwater by announcing the Tide Cold-water Challenge. On a special website (www.coldwaterchallenge.com), this interactive challenge incentivized mainstream consumers to test the product and share the results with friends. An interactive map charted the spread of participants throughout the U.S. – at one time showing upwards of 1 million participants. Other areas of the website underscored the product’s efficacy and associated the brand with energy-efficient products and programs.

The Alliance to Save Energy, an independent not-for-profit group, actively partnered with Tide Coldwater – they have sent email promotions and offer tips on the website on ways consumers can save energy and money. Such direct marketing early on and follow-up efforts, including free samples and opportunities to inform friends through email, set the stage for a successful launch.

A later Tide Coldwater campaign dramatizes how much energy consumers can save by switching from hot and warm water washes. For example, a TV ad promises, “if everyone washed in cold water, we could save enough energy to power all the households in 1,000 towns,” while a more hard-hitting value-oriented pitch claims to “save up to $10 on your energy bill with every 100 oz. bottle.”38

This chapter discussed five of six strategies for successful sustainable brand communications: among them, empowering consumers to act on the issues they care most about, integrating sustainability messages with primary consumer benefits, and underscoring the inherent value of one’s sustainable offerings. None of these objectives can be met if green marketers don’t meet my sixth strategy of sustainable communications, “Be credible” – a subject so important, I devote the entire next chapter to it.

|

The New Rules Checklist |

Ask the following questions to uncover opportunities to add impact to your sustainable branding and communications.

![]() Does our customer know and care about the environmental issues our brand attempts to solve? How do we know? What types of education might be necessary?

Does our customer know and care about the environmental issues our brand attempts to solve? How do we know? What types of education might be necessary?

![]() Who is the primary purchaser of our brand? Primary influencer? What role do children play in influencing the purchase of our environmentally oriented brand?

Who is the primary purchaser of our brand? Primary influencer? What role do children play in influencing the purchase of our environmentally oriented brand?

![]() Is our environmental technology, material, etc. legitimate?

Is our environmental technology, material, etc. legitimate?

![]() Are we asking our customer to trade off on quality/performance, convenience, aesthetics, etc. and asking for a premium price? Are we underscoring primary benefits that our brand can deliver on?

Are we asking our customer to trade off on quality/performance, convenience, aesthetics, etc. and asking for a premium price? Are we underscoring primary benefits that our brand can deliver on?

![]() Are we taking advantage of opportunities to target specific segments of green consumers with customized messages?

Are we taking advantage of opportunities to target specific segments of green consumers with customized messages?

![]() Do our customers know what’s in it for them (versus just the environment, society, or economy)? Does our brand offer any direct, tangible benefits to consumers? For instance, do they help consumers save money? Save time? Protect health? Enhance self-esteem and status?

Do our customers know what’s in it for them (versus just the environment, society, or economy)? Does our brand offer any direct, tangible benefits to consumers? For instance, do they help consumers save money? Save time? Protect health? Enhance self-esteem and status?

![]() Are we tailoring our messages to the specific lifestyles and green interests of our consumers?

Are we tailoring our messages to the specific lifestyles and green interests of our consumers?

![]() Are the environment-related benefits of our brand well understood by our consumers? What types of education might we need to provide? To which consumers would our brand’s environmentally oriented benefits appeal most?

Are the environment-related benefits of our brand well understood by our consumers? What types of education might we need to provide? To which consumers would our brand’s environmentally oriented benefits appeal most?

![]() In what ways can our brand and marketing communications empower consumers to solve environmental problems? Does it save energy? Conserve water? Cut down on toxics? In what ways? By how much? In what ways might we dramatize the sustainable benefits of our products to make our message more tangible and compelling?

In what ways can our brand and marketing communications empower consumers to solve environmental problems? Does it save energy? Conserve water? Cut down on toxics? In what ways? By how much? In what ways might we dramatize the sustainable benefits of our products to make our message more tangible and compelling?

![]() Are our messages upbeat and empowering, and do they use positive imagery? Do we stay away from trite imagery and jargon?

Are our messages upbeat and empowering, and do they use positive imagery? Do we stay away from trite imagery and jargon?

![]() Are there opportunities to engage consumers via a cause-related marketing campaign?

Are there opportunities to engage consumers via a cause-related marketing campaign?

![]() Do we need to reassure consumers about the quality/performance or our product or service?

Do we need to reassure consumers about the quality/performance or our product or service?

![]() In what ways can we generate a buzz among influential consumers?

In what ways can we generate a buzz among influential consumers?

![]() What mix of media represents the best fit with our consumers and our message?

What mix of media represents the best fit with our consumers and our message?

![]() How can we use interactive Web vehicles or social media such as a customized website, Facebook, or Twitter? How might we use You-Tube, mobile advertising, iPhone and BlackBerry apps, and other kinds of experiential marketing?

How can we use interactive Web vehicles or social media such as a customized website, Facebook, or Twitter? How might we use You-Tube, mobile advertising, iPhone and BlackBerry apps, and other kinds of experiential marketing?