A Systems Approach to Marketing Decisions

A systems approach views organizations as unified entities comprising interconnected parts that “hang together” and continually affect each other across time. With a correct approach, these parts can be orchestrated to operate toward a common goal. However, if the relationship of these parts to the overall system is not fully realized, they can work at cross-purposes and hinder the achievement of the organization’s goals. Therefore, effective decision making requires a universal acknowledgment of the larger system, and recognition that few marketing problems are likely to be fully located within its functional silo. More often than not, the scope of the problem and the solutions domain are likely to spread beyond the marketing silo and have broader system-wide implications.

However, each system consists of multiple local actors who have their own sets of biases and experiences. A sales manager is more in tune with the strengths of the selling arm of the organization, while a product development manager is more conversant with the research and development activities. As a result, we find that in most decision-making situations, managers tend to pay the greatest attention to the obvious local symptoms. In other words, they tend to map the strategic problem to their own domain of expertise rather than appreciate its relationship to the larger system. As a result, they ignore promising solutions that account for the systemic nature of problems even when these larger solutions hold the greatest promise.

A systems approach to decision making attempts to encourage such realization, and encourages managers to trace the potential multiplicity of causes of the problem instead of proposing a silo-based and local solution. This is analogous to how a doctor tries to identify the potential causes for a fever, a common symptom. For example, he might rule out infections and identify exhaustion as the immediate source of the fever. Subsequently, he might diagnose hypertension as the source of exhaustion. The diagnosis would lead to medication and lifestyle changes to cure hypertension, plus advice to rest to cure exhaustion.

In our experience, we have repeatedly found evidence that a similar systems approach to decision making provides benefits that could not have been obtained in absence of such a perspective. In one such instance, a client firm was finding it difficult to capture the targeted level of market share for its digital cameras. Independent studies had shown that the quality of its product was comparable to that of others in the marketplace and their brand name was well known in the technology world even though they were relatively new to the world of digital cameras. Their prices were very competitive, and their distribution channel was able to get the product to the desired shelves in the various retail locations. However, we discovered that the problem was that each functional area—pricing, product quality, distribution, and so forth—was looking at its individual contribution in isolation but struggling to come up with an integrated solution since each of them seemed to be performing well individually.

In order to resolve the problem, we invited the multiple functional stakeholders to common meetings, and encouraged them to share their perspectives. In one such session, we asked the attendees to think of how their function contributed to the overall customer experience—before, during, and after the purchase. We repeated the instructions that the attendees should focus on the customer’s experience, trading their functional hats with the customer’s hat. While nothing seemed to come up at first, the solution ultimately emerged in a flash. As the group began building a blueprint of customer-centric experiences, it became obvious that the organization had provided virtually no training or education materials to the retail salespeople in order for them to advocate the product. In the absence of such efforts, the salespeople were unsure of the brand’s product characteristics and shied away from recommending it to potential customers. The marketing strategy was revised, and the firm deployed substantial resources to correct the situation and has since gained market share. While, in retrospect, the solution might perhaps look straightforward, it became clear to the firm and us that the likelihood of discovering it was significantly enhanced by following a systems approach, breaking functional silos, and simultaneously deploying the resources of multiple stakeholders. Under the earlier, silo-based approach, the firm would have perhaps continued to flounder because it would have maintained its focus on product development, pricing, and branding.

Procedural Rationality

Procedural rationality is the other half of our proposed solution that leads to a search for complete and accurate information about the likely relationship between strategic choices and outcomes in order to make effective decisions. It is defined as the extent to which the decision-making process involves the collection of decision-relevant information and the analysis of this information in making the choice. The emphasis here is on “procedural” to highlight the importance of the process, and also to distinguish it from the general construct of rationality that alludes to decision maker omniscience. It therefore takes an opposing view to the “political behavior model” of decision making discussed earlier, which suggests that managers often pursue their own interests, without sharing the whole truth with one another. Such political behavior can then lead to choices based on inadequate or incorrect information, and therefore disappointing outcomes.

Fact-based decisions, on the other hand, are built upon the most comprehensive set of relevant data available, and can help improve the quality of the decision-making process. As Jeff Bezos, the chief executive officer of Amazon.com, once said,

The great thing about fact-based decisions is that they overrule the hierarchy. The most junior person in the company can win an argument with the most senior person with regard to a fact-based decision. For intuitive decisions, on the other hand, you have to rely on experienced executives who’ve honed their instincts. (http://timoelliott.com/blog/2009/02/who_has_the_data.html)

In general, procedural rationality is more important in unstable environments, where things are more fluid and uncertain at any given point in time, and therefore, managers have few similar historical lessons to guide their decision-making process. On the other hand, managers in stable settings are more likely to have an experience-based understanding of their environment, and therefore a lower need to engage in information collection and analysis in order to make effective choices. However, an important deduction here is that if managers have not engaged in experience- and fact-based decision making in the past, then they will continue to make the same mistakes even in stable environments. Therefore, it is important to recognize that implementing fact-based decision making once can lead to more efficient and less erroneous decisions in the future.

The example of a retailer that we worked with illustrates a successful application of procedural rationality. In this case, the firm was seeking higher earnings from the customers that visited its retail outlets. A study designed to provide relevant information to senior executives found compelling evidence for a strong and positive link between the quality of customers’ in-store experiences and their share of category purchase from the firm. In other words, the evidence suggested that customers reporting more favorable in-store experiences were more likely to spend more money in these stores. Subsequent analyses suggested that a key driver of the quality of the in-store experience was the nature of the customer interaction with the frontline retail employees. The next step in the analysis revealed that the engagement level of the frontline employees related positively to their ability to deliver superior customer experiences. Finally, there was undeniable evidence that employee empowerment had a strong impact on the level of employee engagement.

Armed with such information, the retail executives undertook a series of initiatives to better empower their employees, such that these employees could handle customer issues with greater confidence and authority. This included the development and launch of multiple initiatives, all focused on making employees more empowered within the stores. Six months later, there was compelling evidence that employees felt more empowered to handle customer issues and requests. This led to improved levels of employee engagement, delivery of superior customer experiences, and therefore more favorable customer behavior in terms of greater share allocation for the retailer. The investigation path in this case, from a strategic goal of higher earnings to a very specific action item of higher employee empowerment, emerged as the research evolved over time in its quest to finding more diagnostic and actionable information. A standard cookie-cutter approach or reliance on past experience would probably not have revealed the solution and would have led the organization down a less optimal or even an incorrect path.

Decision Flows

So far, we have proposed that we should view an organization as an interconnected system of individual parts that should be orchestrated in designing optimal solutions—a systems approach to decision making. We have also argued that it is important to incorporate a process of fact-based decision making—that is, the need for procedural rationality. Taken together, these two proposals suggest that even though the locus of an individual decision might reside within a specific organizational function or silo, there is a very good chance that both the antecedents of the problem and the consequences of the decision are likely to flow through other functions and touch points. Therefore, in order to evaluate the complete impact of an individual decision, facts and data would need to flow both into and out of the decision across the immediate boundaries of the local function.

For example, a decision to provide additional product training to the representatives of a pharmaceutical firm could lead to better physician experiences during the call by the representative, which, in turn, might then translate to a higher number of scripts written by these physicians for the drug in focus. Now in order to assess the equity residing in the decision to provide additional product training, the training manager can incorporate the data from the anticipated downstream flow of events including the number of additional calls, changes in physicians’ evaluation of the focal drug, the number of additional scripts generated, and their financial consequence. Rust and his colleagues discuss a similar example of a hotel in their work on the “Return on Quality.” In this instance, they evaluated the impact of increased time spent by the housekeeping staff in cleaning the guest rooms. They showed that the increased time spent on cleaning resulted in improved guest perceptions of the cleanliness of their rooms and bathrooms. Consequently, guests had a more favorable overall perception of their room and the stay, which resulted in higher loyalty toward the hotel brand. This flow of effects was used to evaluate the financial return on the quality initiative, which was to increase the average time spent for cleaning each room. What is important to note here is that even seemingly tactical decisions require a fact-based study of the flow of effects across multiple time periods and touchpoints for an estimation of their total impact. For every such evaluation, it is important to identify and operationalize the flow of upstream and downstream effects surrounding the decision, the time lag associated with these effects, and their possible interaction with other organizational decisions.

In recognizing the systems approach to decision making, quality and six sigma experts separate the various relationships of an individual organizational part to other parts as being an upstream or a downstream relationship. Let us stay with the same example of “cleaner hotel rooms” as a focal node in a decision flow. The upstream flow in this case would start from the management’s decision to increase the time spent per room by the housekeeping staff. The next node would be the actual time spent by the staff, followed by the average levels of the cleanliness of the rooms themselves, the focal node. It is important not only to recognize the presence of such flow relationships but also to calibrate them by estimating their direction and magnitude. For example, every additional minute spent per room might not provide equivalent incremental improvement in cleanliness. Similarly, customer perceptions of room cleanliness might taper off after a certain incremental time investment. Most importantly, other actions, such as different cleaning supplies, or higher levels of automation, might be able to achieve the same outcome: a clean room. However, despite a common intermediate metric, a cleaner room, the overall decision flows following from these alternative choices may look vastly different.

Downstream flow relationships, on the other hand, are the consequential outcomes in terms of the benefit and losses that result from the changes in the focal node and the associated metric. In the case of room cleanliness as the focal node, a higher level of performance could potentially lead to more favorable customer evaluations of their specific room, the overall property, or the hotel brand itself. This could translate into a greater propensity to choose the brand, pay a higher price per room-night, or utilize more paid utilities and services on site. More importantly, there would be parallel flows on the employee side. Depending on the upstream decision, employee effort could go either up or down, which could have a favorable or unfavorable effect on their satisfaction, and on their decision to stay or leave. In turn, this chain of events may increase or decrease the cost of retaining, hiring, and training employees. Other potential flows on the cost side of each action would account for changes in the cost of supplies and employee time.

Firms need to evaluate both upstream and downstream relationships not only in terms of their mere presence but also in terms of their direction, shape, and magnitude. It is critically important for them to determine these flows in order to evaluate whether the investment associated with the primary upstream decision will or will not have any equity. If there is no equity, then management may consider investing elsewhere to optimize its resource allocation. For example, it might want to conduct similar flow analyses for other potential choices, such as replacing existing beds with more comfortable ones, redesigning the lobby, upgrading the television sets in rooms, or providing free Internet service. A comparison of flows across the decisions would reveal which decisions have greater or less equity as compared to the others.

Variation in Strategic Flows

It is also important to realize that the structure of flows varies significantly across contexts. For example, the flows from the same decision, say increasing room cleanliness, tends to vary significantly across market segments. Consequently, the equity associated with improving room cleanliness is very different for a luxury hotel chain as compared to a chain in the economy segment. For the luxury brand, clean rooms are likely to be viewed as a basic table-stakes requirement, while for an economy chain, cleanliness can be a performance driver and significantly influence the favorability of customer experiences. The luxury chain on the other hand would not have survived the competitive landscape if it did not already have very clean rooms. The flows are also very different within the same product segment but across two chains with different baseline levels of cleanliness. They are also different across customer segments. We have observed that service quality is typically more important for business customers, brand appeal is relatively more desirable for conspicuous consumption categories, and price tends to be a critical driver of customer retention for commodity goods and services. Finally, the downstream flows from two reasonably comparable decisions, say increasing room cleanliness versus upgrading the television set in rooms, may potentially have widely different flow patterns.

The second important characteristic of flows is that the time lag between certain upstream and downstream relationships can vary. Let us take a personal example to illustrate the point. Imagine that you just moved to a new city to take up a new job, and as you settled into your house, you made three common household purchases. On the very first evening, you went to the neighborhood grocery store to buy things for dinner. As soon as you walked in, imagine that you were pleasantly surprised by the clean and well-lit stores, the competitive prices, and the friendly checkout clerk who offered to assist you with loading the groceries in your car on a snowy evening. The next morning, you woke up to realize you needed coffee and bread and went back to the store immediately—there was almost no lag between your attitudes and behavior toward the store. In this same trip the next morning, you also stopped by the bank in the store and got information on opening a checking account for payroll and other daily transactions. Satisfied with the offer of the bank, and driven by its proximity to your new home, you opened a checking account, and for the next few weeks, you had no unpleasant experiences with the bank. A few weeks later, when the need arose to open a savings account, you went back to the same bank. In this case, the bank accrued the benefit of providing a good customer experience after a period of time. Finally, as you were settling in, you decided that you needed to buy a new desktop computer for your new home. You went through a careful process and then bought a good deal online directly from the manufacturer. As you have been working with the machine over the last few weeks, you have been happy with the performance, and you cannot believe that you got it at such a bargain price. However, it might easily be a couple of years, if not more, before you will have the need to buy another computer for your household.

Similarly, you can think of all recent organizational decisions you have made, and estimate the time over which the flow of effects might manifest itself. In a marketing context, three of the four classic Ps of the marketing mix—product, place, and promotion—are sticky and have long lag periods associated with decisions. A product perceived to be of poor quality cannot make overnight claims of superior quality. Think of American versus Japanese cars before the Toyota braking problems. Customer quality evaluations can be very sticky and customers can be unforgiving, even if the American manufacturers provide objectively better quality. Likewise, the benefits of improved distribution (place) and promotion might not have instantaneous reactions from the marketplace. Of these four classic Ps of the marketing mix, price is the least sticky. Changes in price get an immediate reaction from the marketplace but it also does not last for a very long time.

Finally, our examples so far have been very isolated in that we have assumed that an organization implements only one decision at a given point in time and that future decisions are in abeyance until this decision has flown through all its upstream and downstream relationships. In reality, several organizational decisions are implemented simultaneously or within short spans of time, and it becomes important to understand the interactions among them. For example, the decision to spend extra minutes to clean a hotel room may be made in conjunction with the decision to buy cheaper and inferior brands of cleaning supplies. As a result of such a composite decision, customers might see no improvement or even deterioration in the cleanliness of the room. Similarly, if the extra housekeeping budget comes at the expense of much-needed investments in more comfortable beds—cleaner rooms might not always lead to more favorable overall perceptions of the hotel property. How many of us would want a clean bathroom but an uncomfortable bed to spend the night? Therefore, flows need to be evaluated based on whether the action being contemplated is a singular or a composite decision.

Here is another case study to illustrate the point. A banking firm faced a decision to reduce the number of tellers in its branches in order to save costs and encourage more customers to use other modes of banking such as the automated teller machines (ATMs) and web-based banking. The staff reduction was seen as providing immediate reduction in labor costs for the organization, making it a tempting decision to implement. A systems- and fact-based approach to decision making, however, encouraged management to evaluate the overall downstream impact of staff reduction on higher wait times for in-branch customers, which in turn might have led to customer exodus. In other words, even though there was a single decision on the table there were two countervailing flows to consider. On the one hand, there was the flow associated with reduced cost. On the other hand, there was a parallel flow associated with higher customer exodus. Further, the time frames for the flow effects to be observed were very different. The impact of the cost reduction would be visible instantly, whereas the potential customer exodus would unfold over a longer period. While we repeatedly see this problem, in this case the data suggested that a selective staff reduction strategy was prudent. It was determined that the reductions would initially take place in neighborhoods with a younger and well-educated customer base that had already begun migrating to alternative channels that the bank was interested in maintaining. Similarly, in the case of a credit card operator that was interested in assessing its program of giving cash back to its customers for purchase activity, the data suggested that the incremental customer loyalty associated with this cash back was greater than the hit to the bottom line, suggesting that the bank should continue with the practice.

Strategic Flowprinting

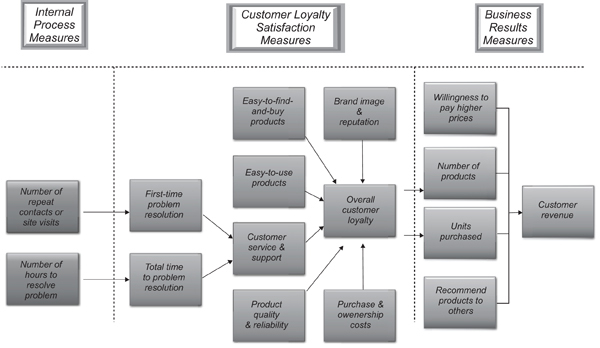

A flowprint is the chart of the upstream and downstream relationships associated with a decision. Let us take a common example of an organization that plans to boost customer satisfaction with the firm. After all, being more customer centric seems like the correct thing to do in most competitive marketplaces. A flowprint would require asking some key questions to relevant, cross-functional stakeholders, and then drawing a system of relationships such as the one shown here for a business-to-business (B2B) technology supplier (Figure 6.1). On the downstream side, for example, the flowprint process might help better understand the financial justification for customer centricity—more satisfied customers might buy other product lines from the technology supplier, buy more units of various products, be willing to pay higher prices, and be more willing to recommend the product to others and therefore generating incremental revenue for the firm. The assumed financial returns of customer centricity are laid out and detailed through a flowprinting process. Similarly, the upstream relationships might be used to identify levers to pull making the organization more customer centric. These might include, for example, investments in brand equity, product quality, and so forth. The flowprint depicted in this illustrative example is a simplified version of more detailed flowprints that are used in actual implementation of strategic decisions.

Figure 6.1. Flowprint: An example.

The flowprint approach is not a cookie-cutter approach to decision making, and has some important characteristics. It encourages the need for systems-based thinking where individual silos are seen as interconnected components of the overall organizational system. It fosters a fact-based decision-making culture wherein managerial knowledge is used to develop hypothesized relationships that are then tested and validated using the available data. Because the process involves relevant stakeholders in hypothesis articulation, flowprinting earns stakeholder engagement by using their inputs into the formulation of linkages for further exploration. Stakeholder engagement also comes from the fact that flowprinting does not impose a standard model across geographies and industries. It is a customized effort that examines the set of relationships articulated by the decision makers themselves. The flowprinting starts a process of ownership because the proposed set of relationships are hypothesized by the individuals who themselves are stakeholders in the outcome of the process. Finally, flowprinting establishes cross-functional participation because it is rooted in the interconnected components of the organization.