The Academic Foundations of Linkage Analysis

As discussed earlier, finding data to analyze is less of a challenge for decision makers in the current environment of data explosion. In order to improve their ability to make superior decisions, managers today are showing an increased interest in models that can help them methodically sieve through the wealth of information currently at their disposal. This newfound interest has led to a review of various new and existing management frameworks, but for the purpose of our discussion, we focus on four of the more popular candidates: the “balanced scorecard,” the “service profit chain,” the “Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Awards criteria,” and the “action profit linkage model.” While each of these four frameworks has clearly provided a unique contribution to the development of management thinking, at their core they all provide the reader with a systematic process of identifying, measuring, and monitoring performance metrics that are most important for the success of the firm. To varying extent, each framework encourages decision makers to broaden their perspective beyond individual organization silos and understand the possible linkages among seemingly disparate measures such as employee engagement, customer loyalty, operational efficiency, and financial performance.

The balanced scorecard1 enables stakeholders to manage their organization more effectively, by providing a framework that allows them to systematically identify important performance metrics across key functions of the organization. These functions include the internal processes of the organization including the performance of its workforce, the attitudes and behaviors of its customers in the marketplace, and key financial measures such as revenue and profit accrued over a period. The key thesis of this holistic and organization-wide perspective is to caution decision makers against a myopic focus on a single set of performance measures, such as short-term financial metrics. For instance, a credit card issuer focused on short-term profitability might undertake an initiative to increase the “late fees” it charges its customers. This might, however, lead to greater customer resentment with the card and lower usage. The intent to boost profits in the short term might then actually lead to eroded customer loyalty, increased customer exodus, and therefore a long-term decline in the financial performance of the issuer. In such a situation, the balanced scorecard framework can provide an early warning signal by reporting ongoing erosions in customer loyalty tied to the late fees.

The key objective of the service profit chain2 is to demonstrate that higher levels of service employee engagement lead to enhanced customer loyalty, which in turn leads to greater financial success. The framework was instrumental in reinforcing the importance of the relationships among internal measures such as employee engagement, external measures such as customer loyalty, and the financial success of the service organizations. We frequently witness such enterprise-wide relationships in many industries wherein, for instance, management commitment to provide tools and resources to its workforce leads to improvements in its level of engagement. Improved engagement, especially among the customer-facing employees of the firm, then leads to improvements in customer loyalty. Higher loyalty, in turn, generates sales growth through more favorable customer purchasing behavior. For example, in the case of a logistics organization, we observed that customers who reported favorable interactions with the sales team and the pickup and delivery employees were more likely to allocate a greater share of their shipping needs to the firm, which in turn led to greater revenue and profit.

The Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Awards criteria3 were instituted to recognize domestic firms that could serve as a role model for others, and increase the competitiveness of the U.S. economy in the global marketplace. These criteria allow an organization to monitor its progress along a set of very detailed and exhaustive performance measures. These measures cover the expanse of organizational functioning, including the performance of the leadership, employee engagement, efficiency and efficacy of internal processes, the feedback from customers, and the financial performance of the firm. The framework emphasizes not only the results achieved on these performance measures but also the approach and deployment of various initiatives that can help the organization sustain such results. In one case study in the technology sector for instance, we witnessed that management’s commitment to improving the efficiency of its internal operations in the customer support centers led to reduction in problem resolution time, which in turn improved the feedback the organization received from its customers in the marketplace. Over time, such improvements in customer experiences led to higher customer loyalty for the firm and more favorable trends in the financial performance of the organization. The firm was able to draw such meaningful linkages because it had measured its performance on different performance metrics such as employee engagement, problem resolution time, customer feedback, and financial activity generated from these customers. More importantly, these measures were stored in databases that could be connected to each other for deriving meaningful linkages among the variables. The key benefit was that improvement targets such as employee engagement and problem resolution success are since regularly quantified in terms of a common language—their financial impact. Previously, the bottom-line impact of such targets was never estimated making the targets themselves less meaningful to top management.

The action profit linkage model4 maps out a structured relationship among the various internal and external success factors of an organization. Unlike other linkage models, it proposes a flexible, discovery-based approach to understanding the true linkages between the portfolio of actions performed by the firm and the financial metrics like long-term profitability or value. It covers all organizational domains and functions and recommends that data and statistical evidence rather than structured prior beliefs drive the linkage analysis. It is not forward prescriptive and does not advocate a suggested course of action for all organizations or for all problem domains. Instead, it suggests that linkages connecting cause and effect could vary significantly across actions and across firms. By implication, it suggests that firms should consider building linkage models backward from the final effect to most appropriate actions in order to discover the best causal pathways. In contrast to the three other models discussed previously, the action profit linkage model encourages a paradigm-free approach to linkage analysis and advocates a sharp focus on actions and their ultimate consequences rather than on any intermediate metric pertaining to employees, customers, efficiency, or costs. It urges organizations to build a repository of linkages through repeated applications of linkage analysis in order to learn the structure of the causal pathways from specific actions to their desired terminal outcomes.

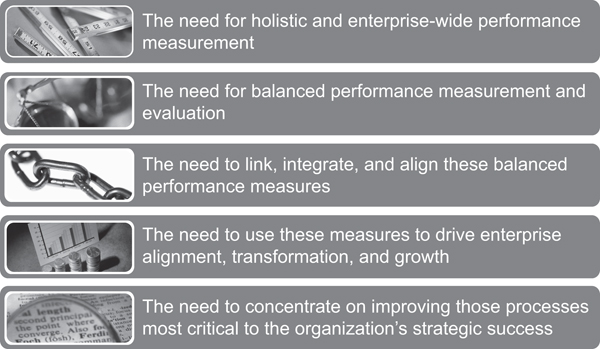

While each of these aforementioned models has provided valuable and unique contribution to the overall development of the management literature, at their core they all have at least five common elements (Figure 7.1). Together, these elements provide a compelling case for linking key metrics that typically reside across various organizational silos that must be collectively viewed as parts of a dynamic and interconnected system.

- The need for holistic and enterprise-wide performance measurement. All the management frameworks discussed here emphasize the need for a holistic and systems-based approach to enterprise-wide performance measurement. Despite this call, we often find that firms, both Fortune 500 companies as well as smaller organizations, fail to take a global view to decision making. Instead, functional silos within the organization, such as human resources or marketing, continue to focus on feedback they gather from their own key stakeholders, without reviewing how such measurement fits into the overall functioning of the firm. Such myopia can be traced to the legacy and history of various organizational silos, the support for certain mental models and metrics among the C-level executives of the firm, as well as uncertainty about the designated executive responsible for a cross-functional view of the organization.

- The need for multidimensional performance measurement and evaluation. Organizational measurement should include valid and reliable5 measures of financial as well as nonfinancial metrics. The frameworks suggest that a common linkage system should bind several measures, such as economic profit and employee engagement, productivity and customer loyalty. They also advocate multiperiod measures, such as leading and lagging indicators, in order to trace the impact of current levels of one measure, such as customer loyalty, on the future levels of other downstream measures, such as financial performance. However, we regularly witness that in the absence of a linkage-driven mind-set, firms allocate their measurement dollars disproportionately to one silo, resulting in a poor measurement architecture that is short on information on areas of performance critical to organizational success. For instance, it is not uncommon to find firms that support multiple, and often redundant, customer loyalty studies but have no measurement system in place to gauge the level of workforce engagement.

- The need to link, integrate, and align performance measures. The academic frameworks discussed earlier all advocate the need for key organizational measures to link and align toward providing compelling evidence of organizational performance. For instance, organizations should confirm that improvements in attitudinal measures of customer loyalty, such as ratings of overall satisfaction, are positively associated with and measures of financial success such as share of wallet, revenue, margin, and profit derived from these customers. Similarly, organizations should invest in confirming other key linkages, such as those between measures of internal operational efficiency, or the ability to resolve the problem quicker, and customer feedback on the quality of the transaction.

- The need to use these measures to drive enterprise alignment, transformation, and growth. The ability to take a holistic view to organizational decision making, as advocated by various academic frameworks, allows managers to compare alternate resource allocation decisions on common metrics of financial outcomes. This provides valuable decision support to senior management in identifying key initiatives necessary to ensure a sustained and healthy growth of their firm. For example, understanding the relative impact of technology improvements versus employee performance in a customer support environment can allow management to allocate resources more effectively toward delivering customer-centric experiences that would justify such investments through enhanced customer loyalty and its downstream financial consequences.

- The need to concentrate on improving critical processes. Overall, the policy advocated by the preceding academic frameworks toward a holistic, enterprise-wide, and integrated measurement system can eventually allow managers to contribute to organizational success by concentrating on those action items that are most critical for success. Organizations that follow this approach can better generate and measure their “return on actions” by identifying the bottom-line impact of undertaking various initiatives. In addition, the cross-functional requirements for such a measurement system can help remove inefficiencies resulting from a silo-based data collection and action planning approach that emphasizes the optimization of function level metrics rather than overall organizational success.

Figure 7.1. The common elements.