CHAPTER 3

Frameworks for Cultural Analysis According to Fons Trompenaars

Contextualizing Background Information

Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner1 have produced frameworks for cultural analysis based on their observations of behavior in companies and also through the collection of data from executive workshops. Even if their methodology has been widely contested by authors from traditional research backgrounds such as Geert Hofstede, who think Trompenaars’ methodology is not rigorous enough, their models have been widely used both in business and in academia for the last few decades.

Some of the frameworks designed by business consultants Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner overlap with those of Hofstede, in particular individualism versus collectivism. Other frameworks are either different or point at the same parameter from a different angle.

Locus of Control

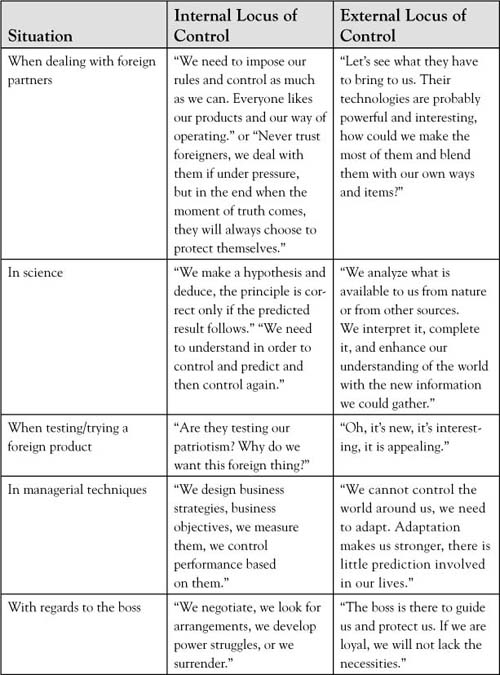

This framework, based on Julian Rotter’s2 categories, defines our relationship with our environment. On one extreme, we have “External Locus of Control” cultures, in which people understand humans as part of nature and therefore must go along with its laws, directions, and forces. On the other extreme, “Internal Locus of Control” cultures are described as those in which people feel they need to master the universe and everything in it in order not to be dominated by its forces. In their minds there is always a dominant and a surrendered, so when deciding whether to adapt to a situation or not it is best to choose not to, as adapting is normally interpreted as a defeat.

The “control” of the world can be interpreted in different ways. Through study and creation we can understand nature and therefore master it through the construction of bridges, dams, and better ways of living. Credit is strictly and specifically allocated to those contributing to innovation and to the discovery of more effective tools that could help the community to live better. A person stealing credit from someone else would be condemned for plagiarism, which is generally considered as a very serious offence by internal locus of control cultures as the search for superior forms of quality life is to be strongly encouraged.

“Control” can also be interpreted as the imposition of one’s own practices over someone else’s. Therefore, in an international merger between companies from internal locus of control cultures, if one party imposes operational procedures, the other will naturally tend to reject them without even giving them much consideration, as this attitude would be interpreted as an attempt to control them.

On the other hand, when dealing with external locus of control cultures, the same company would not face rejection of the procedures, which would even be gratefully received by the other company as new resources to enrich their lives. In fact, they might copy them and resell them, as ideas are not considered as concrete elements belonging to anyone, but simply an element of the environment that surrounds them and is being made available for their use.

The Disneyland Paris case is an excellent example of how similarity in cultural perceptions can often lead to conflict, rather than facilitating interactions. Indeed, when Disney set up in external locus of control Japan, the local society welcomed the company and was delighted to incorporate elements brought in by American procedures and common uses in their own culture after having adapted them. They combined Mickey Mouse and Hello Kitty in a very clever manner, teenagers started considering visits to the attraction park as a traditional step in their dating routine, and overall they “Japanized” Disney rather than perceiving the company as an invader from the West. As an external locus of control culture, they were eager to absorb anything new from the West.

On the other hand, when Disney arrived in internal locus of control France, the society rejected their presence not only because of the perceived image of America as an “Empire,” but also because their practices were considered as a threat to the French way of living and to French values. The “no alcohol in premises” rule was interpreted as “your French wine is not welcome here”; the hire and fire policy was heard as “your French employment laws are not welcome here”; the dress codes were interpreted as “your French fashion is not welcome here”; etc. Overall, Disney in France was interpreted by the French as a serious attempt to control and master French culture by the Americans. It took many years for Disney to revisit their communication strategy and alter their image in France.

Examples of Common Thoughts or Perceptions Typical of Internal/External Locus of Control Cultures

Sequentials and Synchronics

Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner have defined as “sequentials,” cultures in which people imagine time as a succession of passing events that never repeat themselves. In this sense,the past, present, and future are not tightly interrelated or interconnected. What happened in the past is to be forgotten, the present is to be lived, and the future is to be planned. There are also other cultures (synchronic) in which the past, the present, and the future are tightly linked and cannot be separated. The present is at least partially the result of what happened in the past, and the future will be affected by our actions. A mistake may not be very easily forgotten or forgiven because its consequences will not just affect the present, but also the future. Performance in synchronic cultures will be tied to several factors that go beyond “the last man’s act,” which may not be the case with the sequentials.

In synchronic cultures, long-term relationships are of key relevance, because those that we have helped in the past will feel obliged to help us in the future. If we hurt or offend someone, this will come back to us sooner or later, as time is perceived and conceived as a returning factor. Since mistakes are more easily tolerated in sequential cultures, risk taking is more likely to occur.

Time is considered differently in sequential and in synchronic cultures. In sequential cultures, it is perceived as a valuable, precious, and rare asset. In most cases, it can be measured in monetary terms and it should therefore not be wasted. People show respect by being punctual, as we all are worth the same and arriving late to meetings or gatherings means in a way that time is being “stolen” from the other person, who could have made different arrangements otherwise and therefore used what is his/hers to his/her own benefit. Time is an asset that if managed well can lead to success and personal growth, and not allowing other people to decide how to use it best by arriving late can be seen as a sign of disinterest, lack of compassion, and/or rudeness.

In synchronic cultures, on the other hand, time is interpreted as a means to define and underline each person’s role and position in society. The acknowledging of the other person’s role is made by “giving time.”

In synchronic cultures, it is normal to expect senior members to arrive later than junior ones to meetings. This way it is made clear who holds the primary role in society and who “gives time.” Seniors are not expected to lead by example in being on time or not interrupting meetings. On the contrary, they need to display their superior status by acting in exactly the opposite manner from their subordinates. Waiting or making others wait is a tool to signal status and power. For instance, in a similar manner, in synchronic cultures, sellers are expected to wait for buyers (buyers have the money); men can wait for women (it is considered as an act of gallantry to wait for a lady in a bar, whereas the other way round is very rude), and younger for older (synchronics often tend to show appreciation towards seniority as it is widely considered that learning takes time). Status, in synchronic cultures is tightly linked to time, respect, and hierarchy.

Also, in synchronic cultures, time is used mainly to develop trust through relationship building. Dinners are important for business, even if only personal topics are discussed during them. In synchronic cultures, you do business with people you know. And getting to know people takes time. Sequentials, who assume that there is time for business and time for socializing can easily feel unsettled by what they consider as a waste of time. Synchronics can be irritated by sequentials’ lack of sensitivity and tact when showing disinterest in developing a relationship, which for synchronics is the most effective way to avoid trouble in the future.

The following situations illustrate behavioral differences in synchronic versus sequential cultures.

Situation 1

Jim Crafton, a 29-year-old salesman from a small paper company in Missouri, thought it would be a great idea to visit his Greek business partners on his way back home from his honeymoon in Cyprus. So on the last few days of his trip, he made a few phone calls and made arrangements for a few on-the-spot appointments.

Jim managed to arrive on time for the first two meetings with client companies, unlike the local businessmen, who only showed up 15 to 20 minutes after schedule. So, the day of the third meeting, he decided to take the morning to visit a few historical sites with his wife and arrived

20 minutes late at the company, convinced that he was not being rude, just acting local.

This is a typical case of an executive acting in total disrespect of local customs. Not only did he not acknowledge his relatively lower status (being younger, from the selling side, and belonging to a small company) when visiting his business partners “on his way back from a trip” (this lack of delicacy may have been punished by his partners’ tardiness, in an attempt to remind him of WHO is the higher status party), but on top of that, he did not get to his last meeting on time. There is no doubt that his product should be either exceedingly superior in comparison to his competitors’ or that his price must be much lower for this deal to close.

Situation 2

Patrick Bengey arrived in Riyadh, in Saudi Arabia, hoping he would be able to depart on the very next day with his contract signed in order to start his holidays with peace of mind the following week.

He was greeted very formally at the airport, and then driven in a limousine to a huge office where he was extremely well received by Dr. Mandallah, a high-ranking government official, and his numerous crew, all present at the meeting.

Patrick was eager to get to the “nitty gritty,” start focusing on the business matter exclusively and as soon as possible, but his counterpart had arrived over an hour late (Patrick was kept waiting, even though entertained by numerous servants and just people talking to him about generalities of life in the USA), plus when he arrived, Dr. Mandallah only wanted to exchange pleasantries, and show him around.

At some point, Patrick urged Dr. Mandallah to start the negotiation, but he was told that it was a very sensitive matter that needed to be discussed in private, later on.

Getting down to business in synchronic cultures takes time. This is an undisputable fact. One cannot expect to close a deal in cultures in which “giving time” means “respecting others,” by rushing things over or by pushing. The only natural consequence of such behavior will be reticence, distrust, and having the business partner think that one does not really want to do business.

The time spent by Patrick in small talk and in waiting was not time gone to waste. It was time invested in developing a trust relationship between the partners. During this time, the “candidate” to become a business partner was thoroughly studied and analyzed. His product may or may not have been the best, but his capacity to develop and sustain relationships would have been scrutinized in detail.

This type of behavior from the synchronic partner is not illogical at all. In environments where law systems are lengthy and perhaps unreliable, time spent making sure a deal will not end up with conflict of interests becomes a good investment. Because of the time spent in developing trust and mutual support, the chances that one of the parties will switch providers or suppliers or even do anything that could jeopardize the relationship are minimized.

Investing in “getting to know” the potential business partner provides a guarantee that once trust is in place business will flow without unexpected surprises and costly and ineffective lawsuits. Dr. Mandallah will probably pick the businesspartner that offers him a good interpersonal relationship, besides an interesting deal.

Situation 3

Tom, an American businessman, was visiting his supplier in Brazil. He was very excited about the deal and was hoping to have the contract signed within 24 hours in order to make sure production would start with enough buffer time in advance.

Once in Sao Paolo, Tom was invited to join the team for a meal, which lasted for three long hours, during which the origin and making of each dish was explained, wine tasting took place and talks developed from sports to current affairs, family stories, and compliments about the weather.

By teatime, Tom started to get anxious, because when he finally thought they could get into the signing part, his supplier suggested playing a tennis match before dinner.

Tom did not know whether to be delighted, disappointed, or angry, but he did start to suspect that he would not have signed the contract within the next day or two.

There is no doubt that Tom will NOT get his contract signed within the desired 24 hours and he will probably not have it signed within the next week or so either.

The Brazilian friendly approach is a sign of interest in developing a business relationship that will hopefully develop long-term business deals that will multiply in the future as well. An investment in trust and goodwill relationships is therefore paramount to guarantee the successful development of business deals.

By showing his guest around and sharing sports practice on a sunny day, the Brazilian partner is actually “giving time” to his potential counterpart. He is therefore clearly signaling a lively interest in having the relationship develop into fruitful future contracts and joint activities. No cushion time is needed when good relationships are set: friends will always help when necessary to catch up with delays and by absorbing inconveniences.

Tom should relax and enjoy, as this would probably be the best way to make sure the deals are closed and that the partner will not just comply with the agreements they would have jointly developed to everyone’s benefit. Paying too much attention to the hurrying from headquarters and being eager to get results could ruin the whole endeavor. Nothing could be more harmful to this very promising business relationship than a misplaced comment suggesting business is more important, or more urgent, or exclusive of the time he is cordially invited to spend with the Brazilian partner. Needless to say (not always needless, actually), any suggestion that Latin cultures are not keen to work and that they spend their time having fun or that they are lazy (which would be a natural interpretation of the behavior by a Saxon) would definitely lead to the end of the matter and probably of any potential deal happening with anyone directly and perhaps even indirectly connected to the supplier.

In this case, the suggestion for Tom is simple: use this week to improve his tennis service and his smash during the following week, as believe it or not this will be the best way to turn your time into sustainable profits (there are good perks attached to doing business with synchronic cultures indeed).

Particularism Versus Universalism

In certain cultures what ensures stability, progress, and growth is mainly respect of norms and obligations that are determined by society and sometimes established by law. Respect of these rules is paramount to the development of peaceful relationships and general harmony. It is generally assumed that breaking such rules could eventually lead to chaos and therefore exceptions should be avoided. In case of trouble, rules, lawyers, and the established formal system will intervene to solve the problems in a systematic way.

In other cultures, on the other hand, it is widely believed that in fact what promotes harmony and security is not rules, but good relationships. Exceptions and the individual examination of each case, with particular attention being given to specific individuals with whom favors can be exchanged, are important. In case of trouble, it is friends or people we have either helped in the past or who could expect us to help them in the future who will intervene to solve problems in a spontaneous way. Give-give situations are therefore unavoidable, as sometimes formalized rules can be wrong, inapplicable, or perhaps in many cases they could have been developed with the personal interests of the powerful and the corrupt in mind rather than the common good. And people have to be there to fix them on a case-by-case basis. These cultures are called “particularistic cultures.”

Examples of Common Thoughts or Perceptions Which Appear as Typical of Universal and Particularistic Cultures

There is a strong link between universalism/particularism and synchronics/sequentials. As developing relationships takes time, and because relationships from the past will last through the present and towards the future, the time invested in relationships inevitably pays off. Exceptions will be made by particularists in order to favor those they trust. Reciprocity is expected.

Particularists often accuse universalists of being corrupt and vice versa. Particularists think it is shameful to treat members of one’s family with coldness and in the same way other employees are treated. The same is valid in many cases regarding those who do not share similar backgrounds. It is often interpreted as lack of loyalty (“They do not even help their friends, what sort of people are they?”). In a similar manner, universalists consider particularists as corrupt, because they think every person should be treated in the same way and exceptions should not be tolerated. Universalists often accuse particularists of being unfair (“They always help their friends”).

Specifics Versus Diffuses

According to Fons Trompenaars et al., there are cultures in which the status of a person will influence his/her behavior and the perception others have of his behavior in all circumstances. Cultures where this happens more often than in others are called diffuse cultures. In non-diffuse cultures (also called “specific” cultures), status relates to specific situations, when playing specific roles, and is subject to change.

For example, in diffuse cultures as for instance in most of France, the professional role of a senior manager at an important company will spread into all his/her activities, even outside work. In the light of his/her role, such a person should marry someone of similar social status and would not be expected to mix with others from a lower social status (e.g., people would not find it normal that such a person would play tennis with a neighbor who is a factory worker or do his Sunday shopping at the local food market in his sweatpants). In diffuse cultures, one’s behavior, way of dressing, and even language will determine the role he plays in society and there is no break from that role. The role will need to be played at all times and in all circumstances.

Even when social differences exist, as they do in most cultures, there are some cultures in which the roles played by each one of us correspond to specific situations and the personal status may vary according to the situations as well. Hence, the way we operate at work may or may not affect our behavior in private. In such cases, it would not be surprising for people to find their senior manager shopping unshaven at the local market on a Sunday morning in his sweatpants or learning that he recently married his maid, who does not come from a privileged background and has no higher education.

Another difference between specific and diffuse cultures is that in the former, and due to the fact that status is restricted to the particular context of each activity, relationships also tend to relate to each activity or status context. In specific cultures, indeed, people usually relate to specific groups in specific manners, having therefore “friends from work,” “friends from golf,” “friends from the charity,” “friends from holidays in Bermuda,” etc. Relationships relate to roles and statuses that are specific, do not engulf all actions and are not personality-defining; relationships establish quite quickly and then as quickly vanish, as they only affect restricted areas of a person’s life.

People from more specific cultures open up more easily to others and get to know others fast. But these “friendships” or acquaintances can disappear just as quickly. Friends from work, friends from golf, and friends from holidays rarely mix, as the “hat” worn by the person performing these roles is different according to the group they interact with. In diffuse cultures, relationships take longer to be established, but once they have been constructed, loyalty becomes a key value that makes them last longer. Also, relationships affect all areas of the life of a person. Therefore a person will have fewer acquaintances or friends, these relationships may have taken longer to establish, but once the link is developed and strengthened, it affects all areas of the person’s life. In this sense, for a typical person from a diffuse culture, there may be “friends met at work,” “friends met at golf,” etc., but all these friends will probably mix and even belong to the same circles, because they will probably share compatible status and will be looking for external signals to underline this fact.

In specific cultures, for example, friendships and team dynamics can be built during a seminar, an outdoor weekend company activity, or even alongside a conference. Rather immediately, teams could be formed, become operational, and once the objectives that gathered them are accomplished, they would even more quickly dissolve. In diffuse cultures these dynamics sound artificial, as relationships of any kind require time for development. Also, whereas the specific mind can accept the idea of immediately sharing a part of life (professional, relating to the project, specific to a particular activity), the diffuse mind has more difficulties in accepting this fact. In order to relate to someone, to allow someone in your life, it becomes necessary to get to know the person and/or to trust the group. Individuals need to know more about the personal aspects of others before they share time and activities with them. Otherwise, they would not share information or would find working together disturbing.

As individuals from diffuse cultures often circulate within the same circles, whatever goes wrong in their lives will affect their status and relationships in all areas of their life. A mistake, a dismissal, a setback, a failure, or a defeat will be known by his/her whole environment and have consequences in all aspects of his/her life. The notion of “losing face” is therefore typical of diffuse cultures. When succumbing to public shame, individuals from diffuse cultures find refuge nowhere, as everyone will know and there will be no place to which the discomfort will not follow. In specific cultures, on the other hand, the effects of a wrongful situation will hardly expand into all areas of someone’s life, as this is somehow compartmentalized and each part of it is restricted to specific people belonging to specific activities and holding different status symbols.

Because people from specific cultures relate to others in specific situations and within limited areas, they can easily engage in the process of developing new acquaintances, as these will be expected to share only a limited number of activities in a restricted area of their lives. The approach of specific people to strangers will therefore be friendlier and without protocol. This may be considered as “cheerful, glamorous, and superficial” by people from diffuse cultures. Inversely, diffuses will require the necessary time and protocol before allowing anyone into their circle, which may lead people from specific cultures to think they are cold, distant, or snobbish.

Achievers Versus Ascribers

The next of Fons Trompenaars’ frameworks describes what grants status in different societies. There are some societies in which status comes from what people have actually “achieved” and those in which status is inherited or determined by what people actually “are.” These societies are called “ascribed.” Status in ascribed societies can originate from age, social class, gender, background, and other characteristics that are not directly related to what the person has done or will ever do.

There is no society that is completely ascribed or completely achievement oriented. Ascription can be reached by success (reputation) and success can be achieved thanks to the initial “kick” that a favored background can provide. But what Trompenaars signals as the main difference is where status originates, or more specifically, what determines recognition and chances for growth in different societies.

Origins of the social preferences for either ascription or achievement can be multiple. Generally speaking, in environments where change is paramount it is widely understood that those who are younger or at least not too used to old ways of doing things will tend to be privileged, as their capacity to invent and create is supposed to be greater. Inversely, societies where ways of acting have been proven to be efficient and change could only be perceived as an unjustified potential source of risk, seniors or members of groups considered to be a safer option will receive privileges over more diverse alternatives.

The cultural tendency to act more on the achieving or the ascribing side will certainly determine business practices. For instance, delegation is more likely to occur in achieving cultures, promotion will be mostly linked to seniority in ascribed societies, and recruitment and selection will be more likely to be attached to stereotypes in ascribed cultures than in achieving ones.

Emotionals Versus Neutrals

Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner developed a framework called neutrals versus emotionals. According to their data, there would be cultures in which people keep their feelings carefully controlled and subdued. In other cultures, people are called upon to laugh, smile, make gestures, and show feelings.

It is important to understand is that the amount of emotion that people show comes from convention. It does not necessary reflect the level of feelings. Emotionals tend to think that neutrals are cold or that they lack feeling. This may not be the case. They are just brought up not to show how they feel all the time. Neutrals sometimes have the impression that emotionals are immature or uncivilized, because they overrespond or overreact to situations.

Neutrals sometimes have problems trusting emotionals in serious or important tasks because they fear irrational reactions or lack of “cold blood” when needed. Emotionals have problems trusting neutrals because they hide their inner thoughts and therefore they are perceived as “poker faced” or “fake.” Emotionals fear unexpected reactions and backstabbing from neutrals.

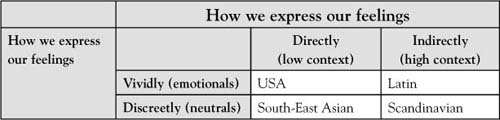

This framework is often confused with Edward Hall’s3 high versus low context. In fact, they are complementary. Emotionals can be either from high or low context cultures depending on whether they express their feelings directly or indirectly. Neutrals can similarly be from either high or low context cultures. The following table produces some examples.

For example, a Latin American, a North American, a South East Asian, and a Scandinavian would tell you that he or she is not interested in going to the movies with you this afternoon in very different ways.

An American would say something like “Oh man, thank you for asking. Unfortunately, I will have to say no this time. You see I am so, so, so, so tired…. But it is great that you’ve invited me. Cheers man!! Don’t overdo it with the popcorn, he he!!!”

A Latin American would say something like “Ohhhh, that is sweet!!! Great!!!! I would like to spend the afternoon with you, but are you sure the reviews are very good? Besides, I have this item I have been dreaming of buying for so long… wait, why don’t we just go shopping first and then go to the movies?” And then the person who suggested going to the cinema will understand the message, go shopping instead, and not bring up the movie again as a sign of politeness.

A South East Asian would say “Oh, cinema, great, I have seen another movie like that once, I really enjoyed it, it was nice. The theatre you are suggesting is really nice, I have also been there another time, it is great. My brother saw that movie and loved it. The actor looks really much younger than he really is and perhaps he will soon get divorced from his wife because, yes, I never thought it was a good couple… mmm… Yeah let’s see… oh, my sister is calling me, please would you give me a second, I will come back in a while…” And then disappear…

A Scandinavian would just say “Thanks, but I do not feel like going to the movies this afternoon.”

Using This Information

Trompenaars’ frameworks provide extra dimensions to the original views by Geert Hofstede. Knowing about them may allow businessmen to enrich their views and perceptions on international partners, which should help them succeed in their interactions by the correct anticipation of reactions and maximization of opportunities that those unfamiliar with such reactions could rarely predict.

Exercises

1. Imagine a business situation in which partners from external locus of control cultures have to deal with counterparts from internal locus of control societies. Describe the situation and present with avenues of potential resolution.

2. Why do you think diffuse people think that asking personal questions can be considered normal, even in business whereas specifics may think that gathering information on personal aspects of business partners is a waste of time?