CHAPTER 7

Cross-Cultural Negotiations

In this chapter different negotiation techniques will be explored, as well as ways in which they are used cross-culturally and how these would contribute to the success of an international business.

Assuming that local assumptions, values, expectations, techniques, objectives, and processes are global is wrong, and traveling to do business thinking international partners always operate as locals do is just a one-way ticket to a wrong deal, or worse, to an unaccomplished one.

This chapter helps understand different negotiation techniques, link them to the frameworks for cultural analysis, and develop tools and attitudes towards better business opportunities.

Contextualizing Background Information

The process of a negotiation can be defined in many ways, including “A process in which at least one individual tries to persuade another individual to change his ideas or behaviour,” or “A process in which at least two partners with different needs and viewpoints try to reach an agreement on matters of mutual interest.” In any case, there are a few defining elements that constitute the essence of a negotiation process, such as: (1) at least two parties, (2) a complementary interest in an exchange, and (3) a potential opposition of interests regarding a give-and-take arrangement.

When the negotiation takes place interculturally, many factors interfere to complicate or sometimes enrich the process. Amongst many other specificities relating to the art of negotiating across cultures, we can mention that in most cases, the parties involved arrive at the table carrying with them different perceptions, cognitions, and assumptions on what is expected and on what is supposed to happen; the interests of the parties may vary in priority and in intensity, and the desired outcomes of the discussions will depend on whether these are designed for the short, medium, or long run.

As negotiating parties tend to think, feel, and behave differently when originating from diverse cultural backgrounds, misunderstandings may arise, and this happens not just at surface level (regarding protocol and body language, for example), but also at a deeper plane, as far as mutual expectations, common practices, and systems of values are concerned.

Issues that may arise when negotiators come from different cultures include, for instance1:

- The type and amount of preparation invested in a negotiation: Universalist cultures will have a tendency to have “done their homework” and will attend the negotiation meeting having prepared all the necessary documentation, drafted contracts, and developed a strategy. Particularist cultures will tend to prepare the basics, but wait until they meet the partners in person and develop a relationship before making any decisions or drafting any contracts. The “feeling” and potential prospects to be constructed will be more determinant than any piece of objective information, so not much can be prepared prior to meeting the partners. External locus of control cultures will equally prefer to leave aspects of the contract “imprecise,” as a means to ensure the necessary flexibility to adapt to the particular characteristics of the business partner and also to the uncertainty of the environment. Not much can be planned in advance, so better to leave the door open. Internal locus of control cultures will prefer to maximize the chances of “winning the game” or “controlling the situation,” therefore they will join the negotiation table well armed with arguments and solid analyses of potential scenarios that they will “confront” the other party with.

- Task orientation versus interpersonal relations orientation: Executives from “doing” cultures will “jump to the task” and maximize the number of actions done by minute. In Fons Trompenaars’ terms, sequentials will try to maximize the output per unit of time invested in the task. Therefore, the schedule of sequentials will be strictly defined and these negotiators will insist on having their timeframes respected. Synchronic negotiators, on the other hand, will want to develop the relationship first and foremost, since to them this constitutes the basis of a good deal: no good business can take place for the long run unless dealings with people are ensured and assured first. Outings, dinners, golf games, gift exchanges, endless protocol, and sightseeing are on the program for synchronics when they do business. “Dating the opponent” is done before “signing the papers” so that when the deal is closed, there will be no surprises and the future of the exchanges will be protected. These series of practices will be interpreted as a “useless waste of time” by sequentials, but in fact they are a wise investment for the future. Once you know someone, you can then concentrate on business without having to incur the transaction costs that are inevitable when your partner is a stranger.

- General principles versus specific details: Negotiators from individualistic, sequential, internal locus of control cultures will require specific details to be stated in the contract in order to ensure that there will be no ambiguities or misunderstandings in the future. Sometimes, people from these cultures will bring lawyers to the negotiation table to discuss matters. The main intention of people from these (generally low-context) cultures is to minimize the room for conflict in future. Negotiators from collective, synchronic, external locus of control cultures see the attempt to pre-state everything as lack of trust and lack of willingness to develop a good relationship for the long term. They would prefer (and see as a sign of goodwill) to agree on general principles and then adapt to specific situations and demands as time goes by and the relationship evolves. If the quality of the relationship is considered to be good enough, negotiators could even go beyond the agreement and deliver more than the contract demands. It is understood that in the long term, a win-win situation is to be achieved.

- In China, the now international term guanxi defines a series of interrelated connections of people who trust each other and who deal in business and in private under a logic of mutual favors. Within these networks, everyone knows there will always be someone to help when in distress, but there is always the pressure of loyalty to give back to those in need as well. In Japan, the term ningsei (in Japanese) also relates to a similar phenomenon, which carries a specific connotation of “sweet codependence,” applicable in business, as much as in family relations.

- Number of people present and the extent of their influence: Negotiators from doing, low power distance, low uncertainty avoidance, sequential cultures would tend to delegate decision making more than others. To them, control means cost, and therefore not maximizing the use of their human resources. This explains why in general the number of people present is lower and the extent of their influence relatively high. Negotiators from high power distance, high uncertainty avoidance, synchronic cultures would tend to centralize decision-making processes and therefore the level of delegation in these cultures is lower and this may require several visits from lowly ranked people before the “big boss” arrives. Or sometimes, visiting parties are constituted by an important number of people, as those in power need to underline their status by bringing their subordinates over with him/her as advisors, trainees, secretaries, or lower management. Whereas negotiators of the previous type might sometimes consult headquarters (in particular their lawyers back home) before making a decision, they will in general have been given relatively more freedom to act and will expect action to take place quite promptly. Negotiators from the opposite type may take time discussing internally and may even wait until they go back home to make a decision or close the deal, but lawyers would not be make visible or sometimes will not even exist. The visible presence of a lawyer could at times be interpreted as failure of the relationship building and therefore the end of any further agreements.

A concrete example of differences that go beyond protocol, but have to do with below-the-surface differences in approach to negotiations due to the cross-cultural idiosyncrasies of the parties can be obtained through the analysis of the standard patterns of behavior of American negotiators when dealing with Japanese counterparts and vice-versa.

Buyer–Seller Relations in Japan and in the United States

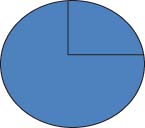

Figure 7.1 schematizes buyer–seller relationships in the United States and in Japan when dealing intranationally and internationally.

On the right of the chart, we see the scheme of what happens when Americans buy or sell from Americans. In general, in this case, the buyer will have a relatively higher status in terms of bargaining power (“the customer is always right”), so the seller will make attempts to please his counterpart, who in this case happens to be the money holder. Having said this, the seller will be expected to push for the interests of his or her company as much as the buyer will be expected to pull for the interests of his or hers. It will be considered as acceptable behavior that the buyer will attempt to have the shortest delivery dates, a minimum price, and payment facilities, as much as a good salesman will be expected to try to limit the benefits and conditions as much as possible without losing the sale.

In Japan, on the other hand, what is expected is a “ningensei” type of relationship, which means a sweet interdependence in which long-term relationships justify the sacrifice of short-term benefits. In concrete terms, in Japan, the seller will give the buyer everything he or she wants, but the buyer will not exploit this “higher status” situation, as a sign of interest in developing a longer-term relationship. In a tacit gentlemen’s agreement, the buyer will not lose face by abusing his or her position of power asking for more than would be reasonable, as much as the seller will make every effort to please the customer or client.

The problem often appears then when Japanese and Americans negotiate. If an American buyer deals with a Japanese seller, the former will assume that his role is to bargain and obtain as many conditions as possible from the seller. The Japanese seller, on the other hand, will at first make enormous attempts to please the buyer, but at some point he or she will find that the expectations of the buyer are unrealistic and that the attitude of the American is pushy and disrespectful. This perception may discourage the Japanese buyer from dealing with this counterpart in the long term and therefore, the negotiation may end right there with no deal being closed.

Alternatively, when a Japanese buyer approaches an American salesperson, he will have an attitude that will certainly be less aggressive than that of the average American buyer. In fact, the Japanese buyer will be expecting the salesperson to accept the conditions without bargaining, and an attempt to alter the proposition could be perceived as a sign of disrespect and a lack of interest in developing links for the long term. The American salesperson may think he or she is doing his or her job correctly by pushing for the interests of his or her company. In fact, even when the deal may not seem the most convenient at first, if there is an interest in relationship building, in the long term the Japanese buyer will compensate those agreeing to perhaps give up some conditions for the sake of a good future business partnership.

In fact, Japanese and American businesspeople perceive both the process and the outcome of the negotiation differently. For the American negotiator, it is about a zero-sum game: whatever one wins, the other loses, just as in sports. Therefore a negotiation is understood as a business process during which each party will try to maximize profit whatever the impact on the partner may be.

The attitude described above is certainly linked to the sequential mindset of Americans, who see life as a succession of passing events, not necessarily tightly linked to each other. Today’s negotiating outcome may or may not affect the future. Next time a deal needs to be made, it may or may not be with the same business partner as others in the market may be offering a more suitable product or service. Each negotiation takes place independently from those of the past and the future. The negotiators even may or may not be employed by the same organization in the future, so giving up on benefits expecting reparation in the long run would perhaps in most cases not make much sense. Besides, Americans are evaluated on performance on a short-term basis (quarterly or yearly), therefore they may be less inclined to sacrifice an immediate benefit in the hope of a larger reward later.

In most American negotiators’ minds, the item that is subject to negotiation is perceived as a cake that needs to be distributed between the negotiating parties. Therefore if one party obtains a bigger share this can only happen through the detriment of the share obtained by the other counterparts. It is therefore a “win-lose game,” or a “zero sum game.”

The “cake” can be divided in half,

or one party can obtain 75% of the cake and the other 25% of it, or one can obtain 60% and the other 40%... but the total sum will never exceed the total amount of the cake to be distributed, as the cake does not grow, but remains the same size no matter what is agreed. A good negotiator in the American mind, therefore, is one who does whatever may be possible to increase his or her “share of the cake,” not just for his or her own personal benefit, but also for that of the company that hires him/her.

On the other hand, the Japanese mind naturally tends to understand the negotiation process as a long-term endeavor. For the Japanese buyer, as much as for the seller, developing a trusting relationship with a business partner requires effort, time, and investment. This is directly linked to their particularistic and synchronic way of thinking, according to which past, present, and future are tightly interconnected, and relationships are the main link between events happening through time and affecting profit, sustainability, and growth. Making a concession will in this context be interpreted as a sign of goodwill, attempting at developing and entertaining good quality long relationships that will generate prosperity for both sides, as opposed to an indication of weakness.

For the Japanese, the key aspect of a negotiation is relationship building, as the outcome of the particular deal is just one link of the chain of events defining a long-term pattern of mutually beneficial exchanges. Japanese buyers, as well as sellers, would attempt to make sure their counterparts are pleased after the exchange, perhaps not out of altruism, but simply because they see a potential profit for themselves in creating a win-win situation.

For the Japanese, therefore, the “cake” does not just get divided; it gets enlarged through relationship building, as all parties concerned will obtain more out of it either in the short or the long run. “Giving one for the team” in a collectivist culture certainly implies that the team protects each player within the big picture. That is why for the Japanese, the search for “positive sum games” and “win-win” situations is key.

The “cake” may be divided in many ways; perhaps there is one bigger portion obtained by one party in the short run, but in the long term, the cards may end up being shuffled differently and the outcome may vary.

A small portion of a bigger cake may be bigger than a whole small cake; therefore enlarging the cake through relationship building becomes paramount.

Other reasons for different approaches to negotiations may be simply practical. For instance, we already discussed the case of frequency in performance evaluations in American companies, which may affect the urgency in obtaining results. A certainty of access to future cash flow is a guarantee of success for an American when facing headquarters. For Japanese businessmen, in view of their long-term orientation, what matters most is market share, particularly in family owned large firms (i.e., the car manufacturing industry). Sometimes therefore and for tangible and concrete reasons that go beyond subjective human perception and behavior, what “makes Japanese click” is not necessarily “what makes Americans click.”

Just to give another example, for the Vietnamese government, which has to face high unemployment rates and sees jobs that offer low wage rates, projects that create working positions are important. For the Swiss government, which experiences low unemployment rates and high wage rates, projects that create positions are not as important, but they may be looking for something else. Therefore, whatever may be tempting for the Vietnamese may not be so for the Swiss.

Strategies for Handling Cross-Cultural Negotiations

Below is a series of examples of successful strategies that were used in cross-cultural negotiations to maximize mutual benefits with minimum cultural shock.

Example 1

An American businessman was put in charge of negotiating the sale of a significant amount of IT materials to an Egyptian group. The buyer offered to pay in trade, but the North American headquarters insisted on receiving payment in dollars. The American negotiator traveled then to Cairo, where he spent a long week socializing and discussing matters with the potential buyer. He participated in excursions, discussions, and sports; by the end of the trip he had not only signed a contract for payment in cash, but also started the development of new markets within nearby regions, thanks to the contacts established during that time.

In acting as a “particularist” and using the relationship to generate trust and mutual gain, the American businessman managed to “enlarge the cake.” Time was invested in this relationship and one of the outcomes was a concession, which was not obtained out of pressure, threat, or a short-term exchange, but as an investment in the relationship which in the long term resulted into a win-win situation (and even a win-win-win one in this case).

Example 2

When American ITT and GCE of France merged in the 1980s, the French counterparts feared a “cruel, heartless, radical, and fearless takeover” and were very reluctant to cooperate and refused to trust their partners.

It was only when ITT lawyers argued that they would be following standard methodology, in full compliance with international law, which had been developed by experts and which had functioned well for a long time, that the French changed their attitude and started to collaborate rather than question.

Taking advantage of the high uncertainty avoidance of the French, the skillful Americans assumed all responsibility regarding the process, which sounded both rational and already tested. When facing what within a Cartesian logic seemed to be a methodology that not only discharged them from the risk involved in such big undertakings, but also seemed logical, well structured, and proved, the French happily—or unhappily—gave in to an operating mode that would easily point the blame away them in case of failure. The Americans, then, had “carte blanche” to go ahead and implement their ways. The success in this negotiation for the Americans was based on (1) convincing the French that there was rationality behind their operations and not just trial and error, and (2) assuming responsibility in the process, liberating their partners from the risk of blame in case the whole enterprise failed.

Examples 3 and 4

When this American multinational wanted to develop trade with China in the business of soft drinks in the 1970s, the first thing they did was to send their most promising chemical engineers for training in Chinese culture, language, literature, music, and history for a year. This was the key differentiating factor that allowed them not only to enter this huge market, but also to lead it.

When former President of South Africa Nelson Mandela was in prison, he spent most of his time studying the language, literature, and all forms of art expression developed by the subculture that had put him in jail and kept him in there for many years. Once free, he explained to the world that it was only through the deep understanding of the ways of thinking and feeling of all South Africans that he could one day reunite his country and lead it towards equality, freedom, unity, and fraternity.

The same way that “ningensei” needs to be more than learned, probably even incepted in order to be successful in dealing with the Japanese, sharing the Chinese sensitivity to interpersonal dealings is key to ensuring a long-term fruitful relationship. It is possible to arrive there naturally and simply. Often this requires effort, as intuition plays a great role in understanding and meta-communicating with others, in particular when they originate from different parts of the world.

Example 5

During negotiations regarding the development and launch of the Channel Tunnel, British and French parties agreed to act and behave local whenever the meetings took place in each nation.

This very specific agreement entails the very British sense of politeness with the very French sense of justice. It is an extremely interesting example of a give-give situation in which two of the greatest empires of the world make an effort to show that they are not attempting to overcome the other nation, but to conclude an international agreement by accepting that the tunnel will be neither French nor English and that therefore there will be no imposition of practices or any threats to established idiosyncrasies. These mutual concessions were proof of goodwill and of the shared impression that goodwill was necessary for the successful conclusion of this important deal.

The Employee/Employer Relationship in Different Countries2

Just as we observed how aspects of national culture can clearly affect corporate culture in terms of Hofstede’s and d’Iribarne’s observations, we can explore in what ways national culture affects intercultural business negotiations within the workplace, in particular in case of international transfers, working with expatriate employees, and other employer/employee situations. A few examples are noted below.

In the United States, the work relationship is considered a mutually beneficial commercial agreement. The employee exchanges time, effort, knowledge, and capacity for employment conditions including salary, career prospects, reputation, benefits, and so forth. This relationship is mostly materialistic and defined and ruled by law. Both the employee and the employer consider their links as professional and would find it natural if either of the parties decide one day to end the contract, as long as the contractual conditions for termination are respected until the end. In this sense, employee and employer, in spite of hierarchical differences (also established and limited by the contract), are basically equal parties trading within the job market. Demand and supply would determine who has more power at each stage of the process.

In Japan and Korea, the employee/employer relationship has a “family” connotation. Even if there is a contract of employment, the relationship is based on a tacit psychological contract with its strongest components being mutual trust and loyalty. The employee will do everything the employer wants, but the employer will not abuse the employee. The employee accepts tacitly that the employer knows more about what is best for the company that is ensuring his survival and that of his family, and he also knows that the employer cares for his own well-being. The employer could be described by a Westerner as a “benevolent autocrat” as his decisions will be accepted by the employee without major arguments. The employer, on the other hand, would not abuse the employee, as that would damage his own image. The employer is supposed to have a duty of decency that needs to be shown by not abusing his power.

In France, the relationship is based on honor and respect for authority. Employers in France know that the most fearful event they would have to face is general grievance, as this is the only movement they cannot control. Tribunals also tend to act rather quickly and to favor employees, so “Proud’hommes” (Employment Tribunal) appears as a fearful word to the ears of a French employer. Moreover, being unemployed is not generally perceived as a shameful state, but as the result of unfair treatment from the upper classes. Therefore there is no great social prejudice preventing employees from setting themselves into the very generous benefits system when and if required.

Apart from that eventuality, employees function under the apathy–rebellion logic. Their opinions are not heard, communication takes place on a top-down, unilateral basis, and a system of filters that prevent feedback from employees to the top is installed. Those filters are in general middle managers who tacitly assume the duty of preventing top managers from being disturbed by daily matters regarding employee’s needs, requests, and demands. In general, employees accept the situation for as long as they enjoy part of the honorable benefits that top managers consent to provide them with and most of the time they develop an apathetic attitude towards what happens, accepting their own fate of submission without even questioning it. As members of a classist society, the French would naturally tolerate the fact that there is a ruling group that at the same time makes the rules and pushes for their compliance on one side and another group that simply complies in exchange for protection. A shared sense of honor amongst the higher class prevents most managers from abuse, and when it happens unions intervene. In general, unions act to preserve the integrity of the lower strata of society, but they hardly ever consider it necessary to help them face managers in a “mano a mano” (face-to-face) confrontation. At best, unions would just take employees back to a tolerable state of circumstances, but never to a place in which they would actually have enough bargaining power to seriously negotiate with the higher class.

In terms of power, the French scheme would be difficult to draw, as the distance of power and logic of honor would well resemble the Japanese buyer-seller status structure. Indeed, the French employer would in this comparative metaphor be the “buyer of workforce,” who does not expect the seller to bargain on his offer, and the employee playing the “seller of work power” who accepts the lenient conditions of the buyer of his workforce without arguing. Within this logic of honor and hierarchical respect, the international customer of goods produced by the company would be an outsider who should respect the honor of the employee by not disturbing him or her with foreign practices to be adapted to (being a worker provides dignifying status that needs to be respected), and even if the seller should accommodate in principle to please the potential client, he will not do so if this means potential trouble with unions or generalized dissatisfaction in-house, as one of the duties of the buyer of workforce services is to protect people who work for him or her.

The foreign customer may bring money in for the short term, but if this means that with his habits and expectations the (always in tension) relationship between employers and employees may be disrupted, then in the long term harmony may be threatened and this would lead to chaos. Therefore, the foreign habits that could be annoying to employees should be avoided even at the expense of losing a short-term deal (the French are particularist and synchronic after all!).

This may explain at least partially why the French are so bad at customer service. They do not see the customer as the one who brings the money that will pay his salary, but as a potential disturbance that employers ought to protect them from as part of the honorable tacit agreement between them.

In the Netherlands, where equality determines and rules over most relationships, employers and employees operate and deal with little hierarchical boundaries. Decisions need to be validated and backed up by consensus and in general discussions are not controversial, but aiming at pursuing the common good. Fairness is a key word and transactions may take time, as consensus needs to be reached and shared by all parties concerned. And all parties are concerned!

Using This Information

Negotiations are behavioral processes that are complicated in nature. When the intercultural aspect enters into play, more complications arise and deals get more difficult to close.

It is easy to fall into the trap of searching for tips that would render the exercise more bearable or easy to close. But it would be advisable to remember that when negotiating internationally, still waters run deep and worse than not knowing how to behave when confronting diverse parties in business is to think one masters their behaviors when one does not. This is probably not just the best way to render oneself ridiculous, but overall it is the surest way to lead any project into failure.

Exercises

1. Based on the reading above, list and explain why and how different frameworks for analysis (masculinity/femininity, uncertainty avoidance, etc.) affect behavior in the cultures described.

2. Imagine how negotiations between employers and employees (salaries, promotions, bargaining through unions…) can take place in the different cultures described. How could conflict situations be handled between and inside these cultures?