CHAPTER 10

Intercultural Perceptions on Ethics

Contextualizing Background Information

The term “ethics” originated in the word “ethos,” which means “customs.” The word “moral ” or “morality,” which is usually used interchangeably with “ethics,” derives from the Latin word “more,” which could equally be translated as “customs.”

Ethics, as well as morality has therefore been understood as the customary way to do things, probably, as opposed to the “sneaky” or marginal way of doing things. Customs are therefore supposed to be “the right way” to act and react and this definition has undoubtedly helped in developing frameworks for action in all cultures since ancient times.

The mere etymology of the word “ethics” therefore suggests that when dealing interculturally there might be misperceptions. If what is “ethical” is what is “customary” and “customs” are—by definition—culturally determined, then what is culturally conceived as “ethical” in one culture may well be considered as “unethical” by another.

The fact that it is commonly accepted to justify a behavior by saying “everyone does it here,” supports our suspicion that people from different parts of the world may see “right” and “wrong” from different perspectives and the consequences of this may be quite relevant.

In this chapter we will explore different views on ethics from the angle of different cultural frameworks. We shall first explore some major objections to business ethics from the viewpoint of different cultural traditions, then we will confront the main modern business ethics paradigms from diverse perspectives, and we will elaborate on cultural relativism in particular with regard to specific business-related issues, such as nepotism, corruption, presents and bribes, and environmental concerns.

Objections to Business Ethics

Psychological Egotism

The first objection to business ethics to be treated is psychological egotism. According to this philosophy, taking people’s interests into consideration when it could be contradictory to the enterprise’s profitability is bad, and even unethical because it is in the nature of each person to protect him/herself first without caring for any others, and this attitude should therefore apply to business entities as well as to individuals to reach fairness.

This self-centered view is not perceived as negative; on the contrary, it is understood as the basis of progress. Within this framework, the role of the leader (either the business leader, or the national leader, or a leader of any sort) becomes therefore to manage interests making sure that they compatibilize in such a manner that the common good or the specific good of the company is reached. But it would be unrealistic to expect people to behave as something they are not—genuinely generous creatures—and therefore it would be dangerous to respond to egoism with altruism.

This psychological egotism objection would certainly be unwelcome to most South East Asian collectivist cultures. The role of the company in these cultures is to protect people working in them, so having to work under a rule that suggests “each one for himself” instead of guaranteeing protection to all would create an enormous amount of discontent. In the psychological contract between most Japanese companies and their employees it is mutually agreed that there is an exchange of protection for loyalty, which honors both parts of the deal.

In fact, the act of manifesting protection underlines the hierarchical distance: the boss protects and the fact that he or she has the capacity to do so underlines his or her status. Another example of a less collective culture with the same logic is France. Each level within the French hierarchy has specified roles to fulfill, and that of the higher ones is to make sure that the lower ones are safe. In return, there is not just loyalty, but the much socially appreciated feeling that one has “cared” for those who are below and therefore the higher position is legitimized.

The psychological egotism objection would find it difficult to survive in feminine cultures, because it is inspired in the quite ruthless idea that each one should care for his/her own interests without assuming any social role beyond that of fulfilling the interests of the powerful.

Particularist, synchronic cultures would find it hard to make efforts that go beyond the minimum to keep their jobs under such premises. Assuming the basic rule for all social and economic exchanges is based on the “you do this for me, I do this for you” principle, a world in which “each one is for himself and by himself” could sound disappointing and hurtful, and quite unfair. In these circumstances, in which there is no chance for trading favors, employees would end up doing the minimum with apathy and no passion, and employers would pay the minimum without caring about the personal circumstances or situation of their employees.

People from external locus of control cultures would react to the principles of psychological egotism with surprise and disgust. Immediately, they would wonder how such a system could be sustainable, as to them, most of the situations in life are beyond our control and therefore everyone should be ready to help others in a crisis to expect the same in return. How would a company in a crisis expect a positive, helpful attitude from its employees if they do not act the same way towards them?

Within an “achieving” cultural context, the psychological egotism principles could be perceived as an incentive to compete for the best position, even if the company is an entity that appears stronger than the individual. In an ideal flexible market, in which the most valuable employees are a rare asset, not owing loyalty can be perceived as a competitive advantage to the employee. In ascribed cultural contexts, on the other hand, such thinking could either be perceived as a potential threat to the status of the highly positioned (who gain legitimacy through charitable giving of what they do not actually need, which is typically French) or as the normal way things are (employees are lazy and do the minimum, therefore they need to be paid the minimum, which is typically Hispano-Latin American).

Machiavellianism

A similar objection is based on the writings of Machiavelli in The Prince,1 and assumes that in order to succeed in business, it is necessary to deceive, lie, cheat, manipulate, use people, alter evidence, lobby, make alliances, generate obligations towards subordinates, gain control over rare resources, and so forth.

According to this view, all sorts of cheating are allowed at any game implying power, because this is what is required to be victorious. In business, as in war, there are winners and losers, and those who do not deceive, lose. Therefore, it is part of business to hurt others.

The Machiavellian objection might not be very compatible with the idea of “good” and “bad” of feminine cultures (perhaps with the exception of high power distance feminine cultures). In these cultures, in which business meetings are longer because consensus should be reached and every aspect of every decision needs to be discussed, manipulation would not serve in the long run, and if discovered would be generally rejected.

In particularist cultures, manipulation is something rather acceptable. As it is common to progress and to achieve objectives through the mutual giving of favors, it appears as normal to generate circumstances in which “the powerful” could owe in order to have him or her feel the need to give back later on. Someone from a universalist culture would see this differently, as when receiving a gift or a favor, he might gladly accept it without having the impression there are any strings attached.

Universalist people (Germans, for instance) would not support the idea of cheating or using people. Brits might digest it, though as if they see it as the only means available to have people do good (i.e., accept unavoidable, but unwanted change, for example), without the use of violence or getting into a conflict situation that would be bad for everyone in the long term.

In high power distance cultures, manipulating, deceiving, and cheating can be perceived by the ranked members of society as a legitimate way to calm less privileged ones down and prevent them from creating a fuss, going on collective strikes, or generating conflict that could get out of hand. The normal and even acceptable general state of “order” could then be reestablished and the system could then continue to operate (for the benefit of the ruling-uneven, unequal class society).

Long-term orientation cultures would find it hard to cope with cheating and manipulation, because for them, forgiving and forgetting is rare. Whatever is done to someone is kept in memory for a long time. On the other hand, much more is tolerated and excused before a business relationship is broken forever, because of the value attributed to its generation and construction.

The Machiavellian view on ethics requires in many cases a very high context communication style. Words, movements, suggestions, references to past events, roles, dissimulated threats, and false compliments are useful ingredients to the whole Machiavellian scenario, and therefore they can be more effective when applied by those with the habit of sugarcoating words. It is also typical of emotional cultures, in which emotional manipulation can often be quite dramatic and explicit. A neutral negotiator can be easily mislead by a partner who slams the door to suddenly come back with an offer, or by a female executive who cries in public to obtain what she wants.

People from achieving cultures may be interested in using some of the artifacts put forward by Machiavellianism in order to justify their access to success, which might grant them enough social respect to compensate for the eventual bad image resulting from a corrupted action. Ascribers may not need to call for Machiavellian actions to access power, as it is given to them automatically by the system. On the other hand, they might have to learn tricks to defend themselves from mischievous attempts at taking profit by less privileged counterparts. This may be one of the reasons why in ascribed cultures, people tend to communicate only with those of their same status or higher and ignore those of lower status. Lower status people are always looked down upon with disrespect, but above all, with suspicion of abuse.

Legal–Moral

The third argument against business ethics is more of a limitation than an objection as such. It states that whatever is legal cannot be unethical and therefore all moral reasoning about what is right or wrong is delegated to decision makers in parliaments, courts of justice, and the like.

This view is highly preferred by universalists, who espouse a natural preference for established general rules to be applied with as few exceptions as possible. Particularists, on the other hand, would find this objection revolting, as the legal norms could well have been established by a corrupted elite, and therefore be extremely biased to say the very least (and highly corrupted to be more specific).

Highly positioned powers from power distant cultures and favored members of ascribed societies may like this argument for as long as they can manipulate the law through lobbying and/or connections. They may also choose to apply the rule when it is convenient to them and disregard it when it will not be to their interest.

Individuals from external locus of control cultures would find this restriction of little logic, as to them unexpected events could easily distort the spirit of the law or a law that once made sense would not make sense at another moment. For example, a rule imposing a health check for a now eradicated disease of all people arriving in the United States by boat from Europe might have been of use in the nineteenth century, but it would be ridiculous to apply it nowadays. Constitutions and legal paperwork are full of these out-of-date legislations, which are often exclusively applied when agendas completely alien to the spirit of the law are in the minds of high decisions makers.

People from achieving cultures may have interests in playing with the limits and the interpretations of the law to achieve their goals, and if information on all legislation in place is not uniformly distributed across ascribed societies, it would become very easy to mislead lower classes into their own exploitation, as they may not be completely aware of their legal rights and could therefore not be able to defend themselves appropriately, even in cases in which the law would be on their side.

Agency Arguments

This objection is based on Milton Friedman’s2 study condemning the doctrine of social responsibility. According to Friedman, managers owe loyalty to their companies and it is their duty to use the stockholders’ resources to maximize their profit exclusively. In Friedman’s view, any action aiming at promoting the common good that has no direct implications on the increase of profitability for the enterprise can be considered as dishonest and must be sanctioned.

The condemnation of the doctrine of corporate social responsibility can certainly be objected from a feminine point of view, as often decisions that benefit companies have serious implications on individual people who are much more vulnerable than a corporation. In fact, when a company goes bankrupt or suffers from a lawsuit, shareholders can only lose the value of their stock, whereas workers can lose their livelihood, their careers, their reputation, and so forth.

Collectivist cultures from South East Asia and high power distant cultures acting under the logic of honor would probably have a similar thought: the interdependent exchange of loyalty for protection is an integral part of the psychological tacit contract between a company and its employees. Employees would not give their best of themselves unless they feel there is reciprocity in the commitment to stand for the satisfaction of their subsistence needs whenever necessary.

Individualistic, achieving, specific, short-term orientation cultures would be a bit keener to support this objection, as companies embracing masculine values of independence and “let the best one win” attitudes are often arenas in which people with high ambitions can develop faster and further.

Bodies of Thought on Business Ethics

Authors around the world have attempted to find ways to define ethical behavior and recipes to describe what good behavior is. In this portion of the chapter, we will briefly describe some of the most popular perspectives on ethics, even if our synthesis on the many and varied existing perspectives is not exhaustive.

Utilitarianism

This philosophy tries to measure the outcomes of each ethical decision in terms of benefits and drawbacks and then approve those that ensure the greatest benefit to the greatest number of people. It has been developed by Jeremy Bentham3 (1748–1832) and John Stuart Mill4 (1806–1873). From the utilitarian point of view, if an action produces more happiness than pain, then it is a good action.

Criticisms to this perspective are multiple, and complex when we measure them from a cross-cultural perspective.

In universalistic cultures, a universal measuring method that could determine what is good and what is bad out of a simple cost/benefit formula would certainly be welcome. The rule being clear and applicable almost mathematically, it would be perceived as fair and objective. In particularistic cultures, on the other hand, many objections would arise, such as who determined the formula, how can one measure good outcomes versus bad outcomes, and they would challenge not only the objectivity of the formula, but also its application in practice. For instance, if in a case of a war the cost was to be measured in terms of lives lost, a particularist would argue that not all lives are worth the same and that it would be inappropriate to create a scale to rank the worth of people’s lives without being discriminatory in any way.

Collectivist cultures would be more inclined to favor such a measure, as in them, “the good of the many outweigh the needs of the few,” whereas in individualistic cultures, each person is supposed to be in search of his/her own lives and ways to develop personally giving a secondary priority to the general outcome of any decision.

In feminine cultures, the ideas of utilitarianism would be accepted, for as long as immediate attention was to be paid to those suffering for the sake of the many. This view would be in way similar to that of long-term orientation cultures, with the difference being that in those, the ones being sacrificed today could find their comfort in the future because at a later time others would be expected “to take the bullet” in return.

People from high uncertainty avoidance cultures might well like the idea of having a formula to determine what is and what is not ethical, as such a guideline would release them from the painful duty of having to decide and risk making a mistake in the process. In high power distance cultures, if the benefit of the many was to challenge the privileges of the elite, this could at some stage become undesirable for the high classes, but very rewarding for the lower ones. In fact, it is not rare to see this principle apply in high power distance cultures, with a slight nuance, though. If the many are to be damaged very little and the small, insignificant sacrifice of the many was to generate a huge, visible benefit for the few, then the decision may even be considered as desirable. For instance, if every citizen was to pay a 0.1 tax to offer an item to their country representative that would be conspicuous, then this might be considered as acceptable… for as long as they have the hope of being rewarded with loyalty and protection on other occasions. Or to prove to foreigners or strangers that their representatives are wealthy and strong (which should reflect somehow on their own image).

Deontology

This philosophical perspective (from Greek “Deo Mai” or “I must”) is based on Immanuel Kant’s5 (1724–1804) “Categorical Imperative,” or set of commandments to be respected at any time by everyone, no matter the circumstances. The basic rule could be formulated as “do unto others as you would have done unto yourself” and never treat others as a means to an end.

This is the ideal of a universalist world in which all the rules can be obeyed by following one precept or a series of them. The deontological ideal of the world would very much suit the uncertainty avoiders, as a simple checklist would suffice to free them from the complexities of having to decide what is right and what is wrong, while protecting them from the risk of a mistake.

From a particularistic viewpoint, or for instance, from an external locus of control one, living by a list of principles could only result in lack of flexibility, either because life is too complicated to be schematized or compressed into a few commandments or because the human mind is not capable of directing, predicting, or stereotyping all possible foreseeable or unforeseeable situations.

Stakeholder Approaches

This trend in business ethics was born as a reaction to Milton Friedman’s objections to ethics in business. Indeed this view favors the understanding of a company as morally bound to respect and balance the interests of not just the shareholders, but of all stakeholders: employees, regional development agencies, shareholders, consumers, suppliers, the environment, and so forth. Contrary to utilitarianism, these more modern approaches see the company’s role as that of a social actor with responsibilities including a fair distribution of wealth and externalities across its stakeholders. This way, it is not just the majority that sees the benefits of the enterprise operations, but everyone is supposed to, in particular the minorities involved.

Universalists would see in this approach a fair option where there is an official system of distribution in place that is respected across the board. Particularists, on the other hand, would see in it an opportunity for manipulation and for the benefit of those who are more powerful anyway.

The stakeholder approach is very popular amongst feminine cultures, which appreciate its capacity to satisfy the needs of the powerful without leaving the fragile aside, and it suits people from high power distant cultures, because in them the unprivileged can certainly have their minimum needs covered and the powerful find it easier to avoid confrontation.

Achievers criticize this approach very often by terming it an obstacle in the natural ambition of humans, who have to pay for those who do not make comparable efforts, and individuals from masculine societies may think similarly.

In long-term orientation cultures, if well communicated, the stakeholder approach can be understood as a series of investments in the future; but in short-term orientation cultures, it may be perceived as a waste of resources, an opportunity for bribery, or the instauration of marginal give/give situations.

Character Virtue

This view promotes the observation and development of the manager or director at individual level, assuming that someone who is basically a good person, can be good, do good, act good, whereas someone who does not have a certain series of characteristics will not.

This perspective focuses on the person, rather than on the system, ignoring whether or not someone would follow his or her values to the extreme when put under pressure.

Particularists would agree with this view, in the sense that a good person may sometimes need to act bad if the circumstances force him/her to do so, but this is part of human nature. What is important is that the person has an inclination to act good, and that is enough, because if such is the case, most of the outcomes of his or her actions will be positive. Universalists would argue that there is no formal way to determine that a person may be officially declared as “good” or “bad,” even if in many universalist societies it is customary to invent or make up approximate ways to determine whether a person is good or bad. For instance, graduates from very strict schools, PhD holders, notaries, and so forth are considered in many societies (in ascribed ones in particular) as virtuous people.

Synchronics would argue that it is impossible to determine whether a person deserves trust or is “good” without having known him or her for a long time. It is through longitudinal analysis of their actions that one can be absolutely sure of someone else’s character. The same argument would work for people from diffuse cultures as well, who suppose it is only after a stranger has passed a series of unofficial tests that he or she can be welcome to the inner circles of friendship.

Cultural Relativism in Ethics

As debated in the previous pages, it would be difficult to create one generic global set of rules that would determine what is right and what is wrong.

Even if Peter Singer maintains that traditions around the world tend to converge, and numerous studies have predicated that every major tradition (Judaism, Christianity, Confucianism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam) teaches the golden rule “treat others the same way you would like to be treated”,6 still it would be naïve to expect all different cultures to share a common ideology on what is good and what is bad.

Cultural relativism suggests that “When in Rome, do like the Romans,” meaning that executives should adapt to local uses and customs and should ignore personal or rules applicable back home when operating abroad.

This viewpoint supports for example, actions that are condemnable by law in many Western cultures, such as bribery, child employment, pollution, and so on, but that are common practice in other areas under the argument that competition may take over, acting like locals, and markets would be lost. On the other hand, local religious rules, dress code requirements for females, and other behavioral impositions found abroad could sometimes block the fluidity of business if ignored or not respected.

Donaldson and Dunfee7 have produced a partial attempt to find a balanced solution between the “reef of relativism” on one side and the “reef of colonial morality” on the other while creating the integrative social contracts theory, which is a set of priority norms to be applied when dealing internationally.

Our own perspective in this sense is that whereas it would be difficult to apply or to impose rules, or else to accept and apply local requirements that seem too strict, the secret consists in finding ways to call for the common spirit of the norms and find common ground. Understanding the origins of rules and sharing them may be a step forward and making a difference, even when this means accepting that some degree of flexibility may be required, is in many cases the solution.

A great deal of patience and enormous emotional intelligence is required, though, to ensure common ground based on other considerations than superficial practices, but it is precisely that extra mile that differentiates outstanding international business players from mediocre ones.

Using This Information

More often than not, it is easy to judge other people’s conduct out of context through stereotyping, in the sense of “Oh… you know, those people from XXX always cheat/don’t keep their word/always think for themselves/never know how to behave/do not know what friendship really is about….”

Whenever business is talked, money is talked. And wherever money is involved, ethical questions appear. A rounded global manager and/or businessperson will certainly be able to understand where other people’s principles may come from. This does not necessarily mean that he or she will have to abide by them, or to practice them, but at least know what is happening and be better prepared to react in the best possible way.

No matter how much effort is being put into designing a global code of ethics, acceptable and practicable by every culture in the world (and some researchers are currently working very seriously in this area), it will be very difficult to find an objective answer to every dilemma.

The preceding text will at least provide the main ideological positions in the matter and hopefully work as a guide to those wondering about the best way to resolve specific issues in different occasions.

Simulated Exercise

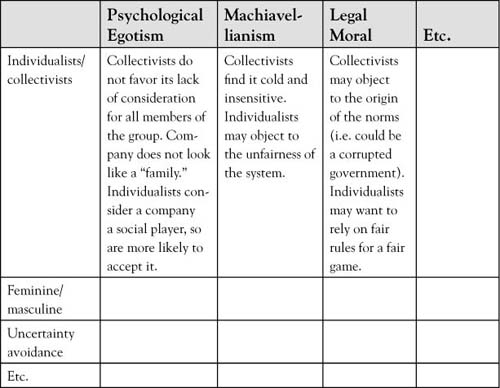

On an Excel worksheet, produce a simulated table crossing different ethical perceptions and objections and frameworks for cultural analysis and complete it.