Creative Thinking in Theory Development

The difficulty lies not in the new ideas, but in escaping the old ones.

—John Maynard Keynes1

Developing theories about the markets you serve is problematic unless you can invest in marketing research. Even if you have unlimited funds, theory development is still difficult, whether you are a physicist or a marketer, because it is hard work.

Many readers of this book work for firms that, for a variety of reasons, do not invest in marketing research. Consequently, although I am writing this chapter for all my readers, this chapter is of particular value to those who work in companies that do not have researchers to conduct studies that help develop and test theories. Why? Because it is better to have a well-thought-out, untested theory that is coherent (see Chapter 9: Coherence) and incorporates good reasoning to support decision making, than just shoot from the hip. If you can’t afford to do marketing research well, you may be better off doing none and relying on your own thoughtful analysis of the situation. “Quick and dirty” research can often mislead because it is poorly conceived and executed. Remember the axiom, “Things done in haste are seldom done well.” Additionally, remember, this book is all about how to properly justify beliefs on which marketing decisions are made, and developing theories of your markets—even preliminary untested theories sometimes called “exploratory sketches”—is the best way to justify those beliefs.

I draw many of these creative thinking, or heuristic, tools from the book, Theory Construction and Model-Building Skills, by James Jaccard and Jacob Jacoby.2 A heuristic is a method that helps you learn, discover, understand, or solve problems on your own. Jaccard and Jacoby’s heuristics are designed to help you creatively develop hypotheses about the many factors influencing consumer behavior in your markets, such as identifying factors most affecting brand selection, without the use of formal research.

Generally speaking, marketers are trying to understand and predict some “outcome variable.” Examples include brand loyalty, product usage level (i.e., heavy vs. light product users), or customer satisfaction. As an added plus, many of the following 19 heuristic tools conceived by Jaccard and Jacoby can be used in product development initiatives.

Analyze Your Own Experiences

Some of us have used the product that is the focus of a theory we are developing (i.e., you may have purchased your company’s own products). Therefore, this heuristic simply has you reflect on past purchases to examine what factors influenced your brand choice. True, this suggestion is based on a sample size of one (i.e., you), and you may not be a typical consumer. But it is a great place to start. Combined with other creative thinking tools, analyzing your own experiences may provide novel insights into factors affecting the outcome variable of interest (e.g., brand preference).

For example, I recently purchased a lawnmower. In reflecting on my experience, I realized that my brand choice was probably affected by what I read on manufacturers’ web sites, off-hand comments the store’s sales associate made to me during my browsing, the point-of-sale materials I found (or didn’t find) on the display models, and the display models themselves. Clearly, these are important considerations for a lawnmower manufacturer to take into account in understanding factors that influence lawnmower brand selection.

Use Case Studies

A case study involves “an intensive examination of a few selected cases of the phenomenon of interest. Cases could be customers, stores, or other units.”3 They come from two general sources: internal audits of a recent marketing experience or depth interviews of a few customers. The motivation behind developing a case study is to intensively investigate a particular outcome variable using the past as a guide.

Before I got into the consulting business, I was a research manager for a computer products firm start-up, Charter Data Products (CDP) in Des Moines, IA. CDP developed a “remittance processor,” which is a computer data entry terminal with optical character recognition used to process remittance payments for credit card or utility companies. Before we designed the product, I got involved in developing case studies examining in detail how a few large corporations came to select the particular brand of remittance processor they did. This effort involved interviews with multiple decision makers in these companies and reviewing financial analyses that they had used to examine the ROI of purchasing one computer brand over another. Developing these case studies took months, and they were quite detailed in their analysis. But the cases provided invaluable insights into understanding how customers made brand decisions. The information was used in the eventual product’s design and development of sales representative training programs. For more advice on how to develop case studies for theory development, see Kathleen M. Eisenhardt’s article, “Building Theories from Case Study Research.”4

Collect Practitioners’ Rules of Thumb

This is what I call “interviewing industry experts.” These can be senior-level executives in your own company; retired executives; and a source I’ve found particularly valuable at times, editors and researchers for magazines and other media. Another great source is academics who are doing research either in your particular industry or in a particular marketing activity of interest to you. You can find relevant articles of interest on Google Scholar and should even consider interviewing the author.

An example of the latter comes from the pharmaceutical industry with respect to how physicians react to marketing and media communications about a product. Understanding how physicians interpret information about products is important in identifying factors that affect physicians’ brand selection of medicines. Ajay Kalra, Shibo Li, and Wei Zhang addressed this issue in their article, “Understanding Responses to Contradictory Information about Products.”5 Their study focused on how marketers could deal with conflicting information physicians received on GlaxoSmithKline’s diabetes drug, Avandia.

It’s not unusual for marketing professors to conduct research in a particular market to test a theory—findings of which you may be able to incorporate into your theories. Go to Google Scholar, type in your industry plus the word “marketing.” You might be surprised at what kinds of articles pop up—some may focus on a particularly relevant area in your line of business. Most of the time, you can get a sense of whether the

article is relevant by either its title or a brief abstract at the beginning of the article. Below are the results of a brief Google Scholar search

I conducted on a few industries.6

|

Industry/Product |

Number of cites on Google Scholar |

|

Automobile marketing |

184,000 |

|

Consumer packaged goods marketing |

40,000 |

|

Cell phone marketing |

49,000 |

|

Dog food marketing |

63,000 |

|

Property casualty insurance marketing |

15,000 |

Use Role Playing

This involves “putting yourself in the place of another and anticipating how this person might think or behave with respect to the outcome variable.”7 For instance, this is what I often do when conducting research for a consumer packaged-goods manufacturer. Recently, I did some marketing research on spaghetti. I went to the grocery story to purchase some spaghetti for a particular meal—spaghetti and meat balls. Of course, I try to keep from thinking like a consultant and just purchase this product as I think the average consumer would. After making the purchase, I reviewed the ideas and feelings that went through my mind during the brand/product selection. One fact that made a particular impression on me at the time was that the store I shopped in did not group the spaghetti by brand; rather, they grouped it by type (e.g., lasagna noodles, thin spaghetti, regular spaghetti, and so on). I was naturally drawn to the brand that had the most of the particular type of spaghetti I was interested in, which was Barilla. If I am like the average household shopper, this was not going to be good news for my client, a smaller-share national pasta brand! Clearly, one of the variables in a model to help management understand and predict spaghetti brand choice had to be shelf placement and the brand’s “footprint” at the point of purchase.

An extreme example of role playing was portrayed by Mel Gibson in the movie, What Women Want. Nick Marshall (played by Gibson) is an advertising executive who gets passed over by another agency executive leading a team to reposition the agency as experts in promoting women’s products. Accidently, Marshall falls in his bathtub and electrocutes himself with a hair drier. The next day, he finds that he is able to hear women’s thoughts, which proves to be an invaluable resource in the creation of ads targeted to women. This is role playing on steroids, and it’s a great movie for all us marketing types to see.

Conduct a Thought Experiment

In a marketing context, a thought experiment is a mental process in which you conduct a marketing experiment in your mind and try to imagine its outcome. Albert Einstein is famous for the thought experiments that led to his development of the special and general theories of relativity at the turn of the twentieth century. We all can’t be an Einstein, but we can do what he did and engage in thought experiments.

A manufacturer I worked with in the past was faced with the decision of whether to promote a particular product using a sweepstakes versus a mail-in rebate. The decision had to be made quickly, and no budget was available to research the issue. So I helped marketing management conduct a thought experiment.

I had recently gone to an industry conference in which the target product was being sold and learned a lot about the consumer decision process by talking to various members of the industry. I was using the “Collecting Practitioners’ Rules of Thumb” heuristic by interviewing industry experts. Based on the information I gathered, plus other background information I had as a result of doing research in a related industry, I ran the following thought experiment in my mind:

• I am a typical consumer who is about to purchase in the product category.

• I come across two nearly identical brands (there is little product differentiation in this product category), with two different promotional offers—one is a sweepstakes and the other is a mail-in rebate.

◦ Nearly all marketers of this particular product offer some kind of price incentive.

• My first impression is to purchase the product with the mail-in rebate.

◦ Why? This is what I believe the typical consumer is thinking:

■ The benefit is certain with the mail-in rebate.

■ The benefit is significant with the mail-in rebate, $50.

■ The benefit for the sweepstakes is uncertain even though the Grand Prize was significant (a trip for two to a vacation resort).

■ The brands are similar … so I’ll go with the lowest and most certain price discount.

The manufacturer went with the mail-in rebate. Clearly, some companies presumably have found sweepstakes more successful than mail-in rebates (e.g., BP’s Win Gas for a Year & MoreTM Sweepstakes8 in support of the 2012 USA summer Olympic team). The point I’m making is that the factors that influence one strategy over another can best be examined by developing a theory that helps you understand what these factors are and how they interact with each other in the consumer’s purchase decision.

Engage in Participant Observation

This is a kind of ethnography, which “is the study of human behavior in its natural context and involves observation of behavior and setting along with depth interviews.”9 Depth interviews are a desirable, but unnecessary, condition for an ethnographic study. You can simply watch consumers, as I discussed in an earlier chapter about my observing consumers purchasing cell phones, which led to the discovery that the sales clerk plays a more influential role in affecting brand choice than my client wanted to admit at the time. A more interesting story about what can come from simply observing consumers is retold by my friend Kent Zimmerman, and is the topic of this chapter’s Thinking Tip.

For many B2C markets, you should be able, at minimum, to observe consumers shopping in your product category at retail outlets. Much can be learned even if you don’t interview the consumer after purchase (something many retail outlets will not give you permission to do). But you can often interview the sales clerk and gain insights into factors motivating brand choice.

Thinking Tip

Below, Kent Zimmerman, tells his story of how engaging in participant observation led to a deeper understanding of factors influencing the brand choice of frozen turkeys, and the invention of a product innovation that is still with us today:

In late 1964, as a fresh graduate of Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, I had to smile when I was hired as assistant marketing manager of Swift & Company’s dairy and poultry department. Dairy and poultry was something I ate, not something

I thought about marketing, selling, or branding.

One of my first projects was for Butterball Turkey. With 100 million pounds or more in annual sales at a premium price that was 3 to 4 cents above other brands, Butterball was a mainstay of the company and the department. It had the largest market share but was starting to lose share points to new brands like Honeysuckle White from Ralston Purina and Norbest from a farm cooperative in Minnesota.

Being the new kid on the block, I thought a grade A turkey was a grade A turkey. After all, it was a commodity! And so, my first line of attack was to review Swift’s market research on the brand. I wanted to know why consumers bought or didn’t buy our brand.

I approached our marketing services department for research on the consumer’s buying habits. I quickly found out there was no research on any of the brands, only market share data based on production information from the USDA. I approached McCann Erickson, our advertising agency that was spending about $4 million a year to promote Butterball. Surely they would have some information. Again the answer nada!

I hypothesized that Butterball’s historical success had to be some combination of brand name, quality image, as well as effective advertising. But now new brands were successfully competing for a larger share of consumer purchases. I asked myself, “Why? What can we do to meet these competitors head on?”

To get a better understanding of the consumer’s buying process,

I suggested to my boss that I study what actually happens at the retail level when homemakers are buying turkeys. It seemed that no one had done this, or if they had, it had never been reported.

The week before Thanksgiving 1964, I visited seven supermarkets in Chicago and seven in the suburbs. My research approach was simply to observe homemakers as they purchased turkeys before Thanksgiving. This was a time in which gas was 35 cents a gallon and a Big Mac, order of fries and a Coke cost about $1.99. The research cost on this project was less than $10.

So what did I find out from my two days of “observational research?” First and foremost, I learned that it is almost impossible for a 125-pound housewife to pick-up a 35-pound frozen turkey, when the one she wants is in the bottom of the freezer case.

When I returned to my office, the general manager asked, “What did you find out?” I described the image of the struggling shopper and said “We need to put a handle on the turkey! It will make it easier for the consumer to pick-up a Butterball — and it should have a positive impact on our market share!”

He pondered a moment or two, and then said, “Why don’t you talk with the Cryovac people, our packaging suppliers, about your idea?”

The rest is history. Over the next 9 months, we redesigned the Butterball package with new graphics, and more importantly we figured out how to put a handle on the turkey! The next Thanksgiving, this packaging innovation was introduced. As expected, it led to a significant increase in Butterball’s brand share. Still in use today, it is one of the reasons Butterball remains the preeminent turkey brand.

So what is the moral of the story? Understanding the buying process is critical to developing strategies that separate you from your competitors. Sometimes the solution is right in front of us, if we would only open our eyes, listen, and understand what our consumer is telling us.

Analyze Paradoxical Incidents

A paradox is something that is seemingly contradictory or illogical, but true. Finding and understanding paradoxes in marketing can provide unique insights for theory development as well as marketing communications. For example, if you are BMW, you might want to interview a good friend of mine, who is 6’8” and purchased a Mini-Cooper, which does not seem very logical. He was in the market for a fuel-efficient vehicle for his 100-mile round-trip commute to work in Wisconsin but did not want to sacrifice fuel efficiency for comfort. Surprisingly, he found that the Mini-Cooper fit his requirements quite well because of the quality of the Mini-Cooper’s interior, especially the ergonomic design of the driver’s seat, and the ability to shift the driver’s seat a considerable distance away from the steering wheel. Thus, considering such a paradoxical purchase suggests that a vehicle’s flexibility in accompanying varying size drivers—even a vehicle as small as a Mini-Cooper—would be a factor in developing a theory explaining brand choice for cars in the Mini-Cooper product category.

Bottom line: Try to find unlikely consumers of your product who have become your customers. Identifying the factors that led them to purchase your brand may provide valuable insights into understanding your outcome variable of interest, such as brand choice.

Engage in Imaging

This is similar to a thought experiment with the vividness of an IMAX movie as opposed to a VHS tape. As Jaccard and Jacoby say in their book:

Try to visualize this situation as graphically as possible and in as much detail as possible. Visualize the setting and the people who are in that setting. Now start playing out the interactions you have with other people. But do not just verbally note these interactions to yourself. Try to imagine them happening, as if you were watching a movie.10

Try to imagine yourself as your customer who has just experienced a felt need for your product. You are planning a dinner and you need a cake mix. Your “oil light” just came on and you need to find a “quick lube” shop to get your oil changed. You are a veterinarian and you know that a sales rep is coming by to talk to you about a new vaccine for dogs. Let the movie roll. Don’t talk to yourself about what you are imagining … just let the movie roll. You go to the grocery store and are having difficulty choosing a cake mix because you’re confused by all the options. You pull in to the quick lube shop and are surprised at how quick the service is—you’ll come back. As the veterinarian, you want to know about vaccine safety in older dogs.

What is occurring in this “movie” is that you are helping to identify factors that influence brand choice and how these factors are related to each other. And this is the beginning of developing a script for your theory. Having a group of marketing executives engage in this exercise will enrich the number and texture of the ideas and relationships you discover, thereby, developing useful hypotheses for creating and testing your theory.

Use Analogies and Metaphors

An analogy is a resemblance between like features of two objects, on which a comparison may be based. A metaphor is the use of a word or phrase to an object or concept that it does not literally denote, suggesting a comparison to that object or concept.

I have used an analogy (comparing one industry to another) by drawing from my experience conducting banking research in the 1980s that applies to most companies. An important “product” of a bank is service, especially when you are waiting in line to conduct a transaction, call the bank with a question, or waiting for a loan approval. What I learned from my research in that market is that service is a two-dimensional construct. There is re-active service and pro-active service. Re-active service focuses on how well a bank responds to an action initiated by the customer, such as the examples cited above. Pro-active service focuses on how well a bank takes the initiative to improve the bank–customer relationship via offering new products, services, or better meeting the needs of customers with its existing product and service portfolio. Analogously, re-active and pro-active services also apply to many other industries and viewing “service” from this two-dimensional perspective can help you more accurately specify the role that service plays in your industry in affecting consumer brand choice.

Developing a theory to help you understand and predict an outcome variable can be problematic. But Harvard Professor Gerald Zaltman thinks that one way to solve this puzzle is through metaphors, as Daniele Pink explained in a Fast Company online article:

The problem, Zaltman says, is that our knowledge of what we need lies so deeply embedded in our brains that it rarely surfaces. Our native tongue is powerless to call it out of hiding; a second, more obscure language is needed. But few who speak to us in the marketplace even know that this second language exists—let alone how to speak it.

‘A lot goes on in our minds that we’re not aware of,’ says Zaltman. ‘Most of what influences what we say and do occurs below the level of awareness. That’s why we need new techniques: to get at hidden knowledge—to get at what people don’t know they know.’

Zaltman invented perhaps the most powerful of these methods. He calls it the Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique—this self-effacing man’s only discernible act of ego. But to most, U.S. Patent Number 5,436,830 (‘a technique for eliciting interconnected constructs that influence thought and behavior’) is known simply as ZMET. The method combines neurobiology, psychoanalysis, linguistics, and art theory to try to uncover the mental models that guide consumer behavior—to illuminate the dark shadows of the customer brain. It is a bilingual phrase book that can narrow the linguistic gap between the marketer and the marketed-to. In other words, in the effort to decode the hieroglyphics etched on the walls of our minds—our emotions, feelings, and fears—ZMET may be the new economy’s Rosetta Stone.11

The idea behind the ZMET method is to identify metaphors that consumers associate with the experience of consuming a product. In the Fast Company article, Pink describes how this method was used in the pantyhose category, and the insights it provided in understanding factors influencing not only the decision to purchase that product, but also which brand to purchase. By collecting pictures of objects that served as metaphors for how women feel about pantyhose, female respondents identified a variety of pictures that reflected their feelings toward this product: barbed-wire (representing the discomfort of wearing pantyhose), a vase with flowers (reflecting the feeling that wearing pantyhose makes women feel that their legs are longer), and a silk dress (connoting a feeling of sexiness). “These findings led hosiery manufacturers and retailers to alter their advertising to include not only images of supercompetent career women but also images of sexiness and allure—even when pitching the product to supercompetent career women.”12

Reframe the Problem in Terms of the Opposite

Assume you are developing a theory to explain why some consumers purchase your product more frequently than others. Instead of focusing on why some consumers purchase your product with relatively high frequency, think instead about the consumers who lie on the opposite end of that spectrum—nonusers or “light” users. For example, consider instant potatoes (mashed and casserole) at the grocery store: focusing primarily on “heavy” category users might identify issues promoting heavy usage such as the product variety offered, the product’s relatively low price, and the brand’s image. But trying to understand why other users purchase the product relatively infrequently or not at all might identify additional factors important in developing a theory about why and how frequently consumers purchase in this category—such as the perceived unhealthiness of prepackaged foods, desire for fewer serving sizes per package, or the use of couponing by competitors.

Another related example is developing a theory to understand customer satisfaction. Take a B2B example in the chemical industry. Factors driving satisfaction may be related to prompt service delivery, accurate invoices, and competitive pricing. Yet, factors most predictive of dissatisfaction might be unreliable supply, variance in product quality, or poor service in responding to customer complaints.

Change the Scale

To explain how this creative heuristic can be used to help develop insights into factors affecting some marketing outcome variable, consider a walk-behind lawnmower. How would the consumer’s brand choice, for instance, be altered if we changed the scale of some of the lawnmower’s attributes, such as increasing: (1) the engine’s HP from 6 to 12, (2) the size of the cut from 22" to 35" or, (3) the size of the wheels from a 4" to 8" diameter? Even if you cannot conduct a formal marketing research study to test the effects of these changes, one idea becomes abundantly clear: As you increase the scale of these attributes, consumers will reject a walk-behind lawnmower if the engine’s HP is big (mower becomes too heavy), size of cut is too wide (mower is too hard to maneuver), or wheel size is too large (mower is difficult to push and turn corners). This means that, in developing a theory of a marketing outcome variable such as lawnmower brand choice, you need to take into account the “ideal level” of the product attributes that make up your product.

Focus on variables

To better understand this creative thinking tool, you might want to review Chapter 8: Causality. One of the points made in that chapter is that rarely (if ever) does a single product attribute affect a marketing outcome variable such as brand preference, or heavy versus light product usage. Generally, a group of variables interacting together is involved in affecting brand choice. Recall the conclusion of INUS conditions:

The primary implication of INUS conditions to marketers is the following: The task of understanding cause and effect as it relates to consumer purchasing behavior can be complicated because no single factor influences a given consumer to consider your brand. You may have a competitively priced product, but price generally interacts with other aspects of your product offering in affecting what the consumer considers and ultimately purchases. Bottom line: Do not think about how you can optimize a particular attribute of your product offering, but rather focus on how to optimize a system of product attributes that, working together, can influence consumer purchasing behavior.

Therefore, in developing theories about your markets, identify how product attributes interact to influence a marketing outcome variable.

Consider Abstractions

This idea relates to Chapter 7: Attributes Versus Constructs. The major lesson of that chapter is that the roles individual product or consumer attributes play in affecting brand choice are less important than grasping the underlying perceptual constructs of products or the psychological constructs of consumers that affect brand choice. Chapter 7 gave several examples of this:

• The more successful vehicle manufacturer changed the aerodynamic styling of their minivan versus changing individual attributes of the minivan’s styling.

• The more successful financial institution differentiated between proactive and reactive service, rather than thinking of services as an unrelated collection of different attributes.

When developing theories about marketing outcomes, incorporate constructs, not merely attributes, into those theories.

Make the Opposite Assumption

Take an important foundational belief about your market, and assume that it is not true. Think through its implications and see if it leads to a hypothesis about some relevant outcome variable.

For any given market, you can make the assumption that this market is not homogeneous but rather heterogeneous—it’s a market composed of many different market segments. I did a study recently on genetics products for dairy producers. The hypothesis going into the study was that dairy producers were relatively homogeneous with respect to the products and services they wanted from firms that provide these products and services. The research suggested that this belief is false. Some dairy operations want more consultative-type services together with the product they purchase—bull semen; others simply want the product. This finding is important in developing a theory explaining factors that lead to brand choice in this market.

Another example is one in which you ask yourself if your firm’s advertising has most of its effect in motivating first-time or subsequent purchases of your brand. “For example, a consumer may purchase tires recommended by a friend and then develop a favorable attitude toward the company and pay closer attention to its ads to reduce dissonance.”13 An example of this situation is reflected in print advertising Michelin has run in which they promote the number of awards their tire brand has received. The objective is to instill a feeling of confidence in their current customer base, thereby motivating these consumers to purchase Michelin in the future.

Apply the Continual Why and What

Given an outcome variable, such as the likelihood of a consumer purchasing your brand, ask continual “why” questions until unproductive. For example, assume that you work for Honda Power Equipment and that you are building a theoretical model to explain brand preference for lawnmowers. Consider the following series of “why” questions:

Q: Why do consumers purchase Honda lawnmowers?

A: Because they are reliable.

Q: Why do these consumers perceive that Honda lawnmowers are reliable?

A: Because they perceive the Honda brand to be high quality.

Q: Why do they hold this belief?

A: Because they’ve owned Honda automobiles and have had a positive experience with the brand.

This line of questioning suggests that a theory explaining brand preference for Honda lawnmowers should take into account consumers’ perceptions of Honda automobiles.

Consult your Grandmother—and Prove her Wrong

This creative heuristic was invented by the sociologist W. J. McGuire in an article entitled, “Creative hypothesis generating in psychology: Some useful heuristics,” in which he coins the term, “bubba psychology.”14 Here’s the idea: identify some conventional wisdom about your product or market, and try to prove it wrong. For example, nowadays it’s “conventional wisdom,” to think that you must promote your product via social media (e.g., Facebook and Twitter). Try to prove this wrong. In the process of doing so, you might generate some hypotheses regarding factors that influence marketing communications effectiveness. For instance, you may conclude that, indeed, Facebook is a great medium to influence attitudes about your brand because a significant percentage of your customers are not exposed to most mass media (e.g., TV and radio). In contrast, based on my experience in the personal property casualty insurance market (e.g., car and home insurance), social media does not appear to be having much impact on building loyalty among current customers, or bringing an insurance company new customers. What’s more boring to consumers than a Facebook page for home insurance? This heuristic, therefore, may help you identify, in broader relief, factors that influence brand choice such as identifying effective marketing communications media.

Read In and Outside the Immediate

Field of Marketing

The more you know, the better able you will be to develop theories to help explain and predict marketing phenomenon. As you have read in this book, marketing knowledge in most of the twentieth century contrasts starkly with marketing knowledge of the twenty-first century. Our field is quickly becoming a multidisciplinary domain that is being informed by other subject areas such as psychology, sociology, BE, and neurology.

The major recommendation of Chapter 9 on Coherence is for you to enlarge your marketing belief system by exposing yourself to multiple sources of knowledge (e.g., reading books and articles, conducting research on the Internet, and even watching relevant YouTube videos). Additionally, information sources not typically considered “marketing focused,” such as Wired (“How to Spot the Future)15 and The Economist (“How to Make a Megaflop”),16 often have articles of relevance to marketers. More knowledgeable marketers create more useful and coherent theories.

Shift the Unit of Analysis

Often when thinking about why some people purchase your product and others don’t, your unit of analysis is the individual customer. Shift the unit of analysis to other relevant groups, such as couples or families. For example, consider that many consumer products are often chosen jointly by two adult partners in a household. Think about what factors might come into play in a product decision if you think about how these two adult household members interact in their purchasing decision, versus thinking exclusively about the single adult who actually makes a purchase at the store.

If you work for an organization that sells to businesses, shift the unit analysis from the decision maker to the department or company. Often, in B2B decision making, no single employee controls 100% of the purchase decision. From this perspective, consider others in an organization who might influence the purchase decision, such as Gatekeepers (employees who control your access to decision makers) and Influencers (those who indirectly influence decisions), as well as the actual person who makes the purchase. Change the focus of a question such as, “Why does this particular person purchase Product X” to “Why does this company purchase Product X?”

Draw Molecule Diagrams: A Picture

Is Worth a Thousand Words

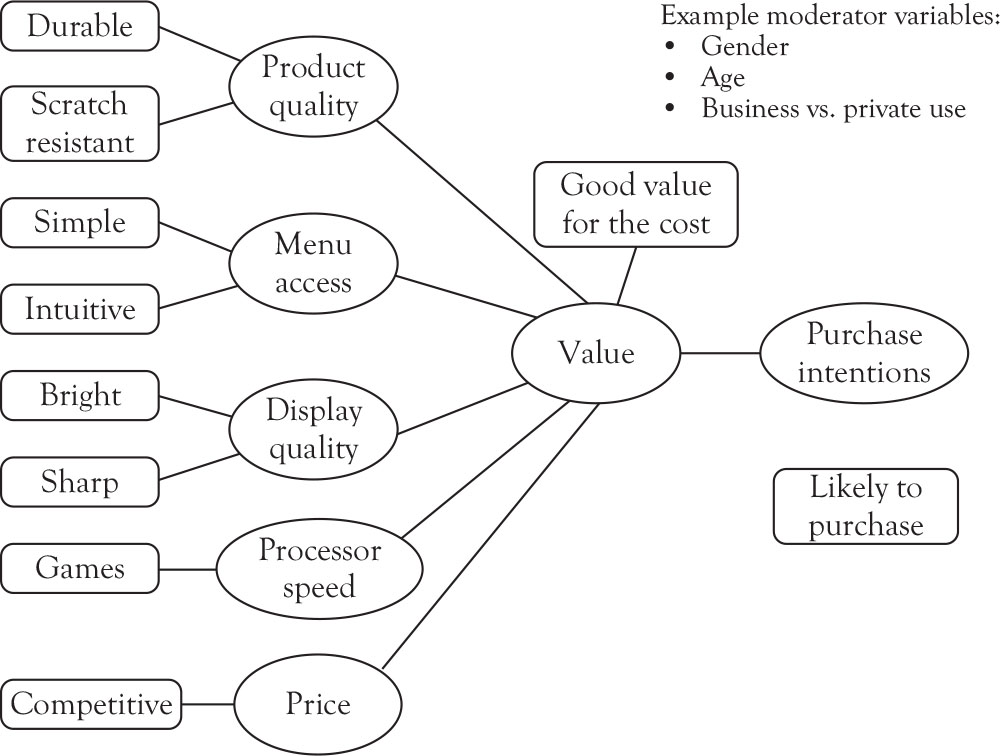

This final heuristic tool is one that I use most often. I draw molecule diagrams identifying factors that might explain a potential outcome variable. The following is an incomplete example of a molecule diagram representing factors influencing the purchase of a cell phone.

Figure 13.1. Example molecule diagram.

The idea is to define all relevant factors (e.g., “constructs” as discussed in Chapter 7), represented by the ovals, that you believe influence some outcome variable, such as purchase intention. Then, brainstorm the “indicators” or measures of those factors, denoted by the “rectangles.”

Additionally, explore whether the relative influence of the different constructs differs among certain consumer segments (i.e., “moderator” variables as discussed in Chapter 8: Causality) such as male versus female or older versus younger consumers, and whether the phone is used primarily for personal or business purposes. Such a diagram can prove to be a valuable focal point in brainstorming with colleagues what factors should be included in this diagram.

Finally, the more fundamental lesson regarding these molecule diagrams is that creating them—or simply writing out your hypotheses and assumptions that support your marketing propositions—forces you to clarify your thinking (see Chapter 12: Arguments and Logical Fallacies) and gives you something to share and brainstorm with others, as well as providing a historical record of your thoughts.

Chapter Takeaways

1. Use creative thinking tools to develop hypotheses and theories about the markets you serve. Colloquially, a hypothesis is part of a more general theory (e.g., a hypothesis that proactive service is an important factor in an overall theory of factors explaining customer bank loyalty).

2. Even if you cannot conduct marketing research to test your theories, it is still important to develop preliminary theories to guide decision making. To have a well-thought-out, untested theory that is coherent (see Chapter 8: Coherence) and incorporates good reasoning to support decision making is better than merely making decisions shooting from the hip.

3. Use some or all of the creative thinking heuristics in developing your theories.

a. Analyze your own experiences

b. Use case studies

c. Collect practitioners’ rules of thumb

d. Use role playing

e. Conduct a thought experiment

f. Engage in participant observation

g. Analyze paradoxical incidents

h. Engage in imaging

i. Use analogies and metaphors

j. Reframe the problem in terms of the opposite

k. Change the scale

l. Focus on attributes

m. Consider abstractions

n. Make the opposite assumption

o. Apply the continual why and what

p. Consult your grandmother—and prove her wrong

q. Read in and outside the immediate field of marketing

r. Shift the unit of analysis

s. Draw molecule diagrams