“When God said, ‘Let there be light,’ He surely must have meant perfectly coherent light.”

—Physicist Charles Townes commenting on our ability to understand the secrets of the universe

What Is a Belief?

A belief is what we accept to be true. For discussion purposes, when I refer to a “belief,” I am referring to a propositional belief, as opposed, say, to moral, religious, or political beliefs. For example, “The most significant factor affecting the purchase of our product is its perceived quality,” is a propositional belief. Your propositional beliefs about marketing help shape the marketing decisions you make.

Clearly, managers hold more confidence in some beliefs than others. For instance, depending on the nature and appeal of your product or service, you may assign a higher probability to the belief that advertising your product or service on the Internet will lead to increased sales, while assigning a lower probability to the belief that promoting your product or service in newspapers will increase sales. Nonetheless, in applying scientific reasoning to marketing, a fundamental question that you need to ask yourself is:

“How justified are my beliefs that support a given strategy or tactic?”

Why We Need to Justify Our Beliefs

Your first reaction to that question is probably, “I’m highly justified—of course!” We are usually guided to this assumption by our experiences. Many of our marketing beliefs are based on what we have seen work or not work in the past. However, as discussed in the previous chapter, Scottish philosopher David Hume contends that beliefs based on what-happened-yesterday-will-happen-tomorrow are often unjustified. This book cites many examples of organizations stubbornly sticking to historical business models—which are really propositional beliefs about how to run an organization—that drove them off a cliff (e.g., Nokia, Brunswick, and Borders). Consequently, the more justified one’s beliefs are that inform and shape business decisions, the greater the likelihood those decisions will be successful.

How, then, can you go about justifying your beliefs?

The Meaning of “Coherence”

One tool to help you answer this question is called the coherence theory of empirical justification, or simply “coherence,” for short.1 Coherence “is a matter of how well a body of beliefs ‘hangs together’; how well component beliefs fit together, agree or dovetail with each other, so as to produce an organized, tightly structured system of beliefs, rather than either a helter-skelter collection or a set of conflicting subsystems.”2 Philosophers use the term empirical to refer to knowledge obtained by experience—in our case, a marketing manager’s experiences and how those experiences lead to knowledge—as opposed to knowledge that does not depend on experience for its justification, such as logic or mathematics.3

Assume you have proposed to senior management that increasing advertising expenditures on your product line will increase your company’s profits. Your proposition is based on several beliefs you hold, drawn from personal experience. For example, you may have taken an advertising course in college and your textbook said that increased advertising can increase profits. Your professor may have corroborated that belief with examples from her experience. Additionally, the professor may have reviewed various theories of how advertising works, and these theories are applicable to your particular situation. Even further, you may have been directly involved in other projects where increasing advertising expenditures resulted in increased sales and profits. The proposition, “Increasing advertising will increase our profits,” is in a sense “justified” by your belief system—an interconnected web of beliefs—such as the one below:

1. I read in a college textbook that advertising can increase profits.

2. My college professor agreed with the textbook.

3. I trust my college professor; therefore, I also trust the textbook.

4. I trust my college professor because she works at a respected university, which I trust to hire competent professors.

5. My college professor gave many “real world” examples showing that advertising did increase profits for companies.

6. I worked for a company whose research showed that increasing advertising increased company profits.

7. I trust the people who conducted that research.

8. The situation I am in now is similar to others I have read about.

9. I have personally experienced situations in which increasing advertising expenditures grew profitability.

10. I trust what I observed in these situations.

See the pattern? The above belief system is like a “web,” in which all beliefs are related to each other, either directly or indirectly. The above belief system is only a partial description of an entire belief system. Any belief in the list could be expanded. For example, the belief, “I trust my college professor because she works for a respected university,” could be expanded by linking it to other beliefs that support your belief in the university, such as the following:

• I have friends and associates who have graduated from that university who have been successful.

• My university is nationally ranked.

• I have only read positive stories in the media about the quality of the education it offers.

How Coherence Theory Can Help

A belief system, therefore (emphasis supplied), “is essentially systematic or holistic in character: beliefs are justified by being inferentially related to other beliefs in the overall context of a coherent system.”4 With this as background, we can now develop the following working definition of coherence:

You are justified in holding a target belief to the extent that it is logically connected, directly or indirectly, to other relevant beliefs that are themselves logically connected to each other, directly or indirectly, and all beliefs are empirically based and self-consistent.

Let’s expand on these last terms a bit:

• Logically connected: Beliefs that reasonably or inevitably follow, one to the other. For example, accepting what you read in a textbook is based on a personal experience in which you had a trusted professor who used that textbook and said it was trustworthy. These beliefs arose out of a natural sequence of events logically connected in time and space. Additionally, logically connected implies that a belief system possesses the following properties: clarity and mathematical/logical soundness.

◦ Clarity means that a belief system minimizes the use of vague or ambiguous terms or ideas. For example, we discussed in an earlier chapter that the concept of “importance” is a vague term. Therefore, the proposition, “We need to advertise the superior performance of our product on Attribute X, because Attribute X is important to consumers,” is faulty because the term “important” is ambiguous. Consequently, ambiguous use of terms such as “important” in a marketing belief system diminishes its validity and “coherence.”

◦ Moreover, to the extent beliefs are supported by mathematics or formal logic, errors in these areas clearly weaken a marketing belief system’s validly. For example, a marketing belief system may be influenced by a marketing research study that your organization conducted. If that study were to have a logic or mathematical error in it—for example, a statistical calculation was made incorrectly, an inappropriate research method was used, or the study failed to measure an influential factor affecting consumer behavior—the beliefs that were informed by that study could be severely compromised.

• Empirically based: Beliefs derived from personal experience—what you see, feel, touch, smell, hear, and, ideally, test experimentally.

• Self-consistent: You cannot both accept and not accept the same belief, such as saying both “I trust the people who conducted the research,” and “I do not trust the people who conducted the research.”

Therefore, a belief is justified to the extent that it is part of a coherent belief system. The more coherent a belief system is—that is, the more it possesses the properties discussed above—the more truth-conducive it is. And it follows that the more truth-conducive your marketing belief system is, the more successful your marketing decisions will be. Obviously, organizational politics and financial realities also inform marketing decisions—but I leave dealing with those topics to other authors.

Thinking Tip

An important property of a coherent marketing belief system is that the terms and individual beliefs in the system are clear, unambiguous, and accurate. Earlier in this book, I introduced you to the concept of “importance,” an ambiguous term that can crop up in marketers’ beliefs (e.g., “We need to deliver what is important to our customers!”) that only serves to cloud one’s thinking. Now, I want to introduce you to another ambiguous term that also muddles up one’s critical reasoning skills: “expectations,” as in the statement, “We want to exceed our customers’ expectations.” Research has shown that when you ask consumers about their “expectations” of a product or service, consumers’ interpretations of that term can vary widely.5,6 For example, assume that you are a car dealer who wants to “exceed the expectations” of your customers’ experience when they have their car serviced, and your focus is on how long the customer expects to wait for a regular service visit. In this context, “expectations” can take on the following meanings:

• Forecast: A forecast of how long customers believe they will have to wait, based on past experience

• Acceptable: The longest acceptable wait before customers become agitated

• Deserved: The longest acceptable wait can differ based on how much a customer paid for a new vehicle. For example, customers who purchased a Ford Focus may have a longer “acceptable wait” than customers who purchased a Lexus. The more customers pay for a new vehicle, the more they feel that they deserve better service.

• Feasible: The shortest but feasible wait time. In this context, customers’ expectations are based on what’s possible for the dealer given the current situation. For example, a customer may expect a shorter wait time if she made an appointment to have a vehicle serviced as opposed to driving to the dealership without an appointment.

Expectations are not only ambiguous, but when this concept has been included in statistical models to predict consumers’ perceptions of perceived product/service quality, or customer satisfaction, those models perform no better than those that only measure perceived product or service performance.7

Rather than try to understand your customers’ expectations, you will be better served by trying to understand the optimal feature configurations of your product, and “how much” of each feature your product should possess in order to maximize profits over the long run. This often involves understanding the “trade-offs” consumers are likely to make with respect to product features and price (e.g., Is a consumer willing to pay X% more to get a higher-quality product?).

Admittedly, this task is not easy. But if you do not know how to think scientifically about this issue, nonscientific reasoning will get you nowhere.

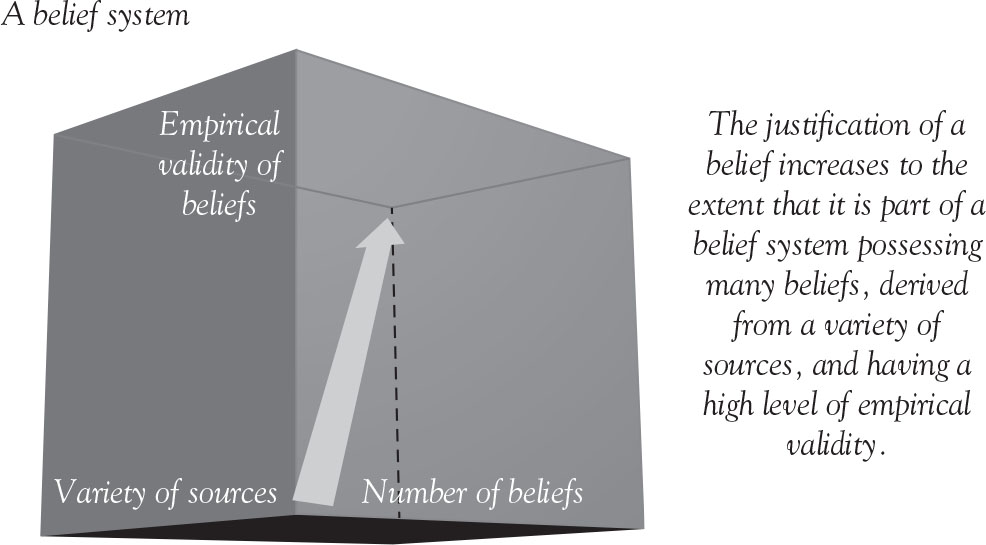

Important Properties of Coherent Marketing Belief Systems

As you might suspect, seeking to justify a belief or a related system of beliefs is a journey, not a destination. We are, therefore, left with trying to justify the belief systems that shape and inform marketing decisions by making them as truth-conducive as possible. We can do this best by conceptualizing the coherence of a belief system as lying in three dimensions, as measured by (a) the number of individual beliefs in the system, (b) the variety of sources from which those beliefs are based, and (c) the extent to which these beliefs have been empirically supported through testing, which is a measure of their validity.8 The more “coherent” a belief system is, the more truth-conducive it is. See Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1. The three components of the coherence theory of empirical justification.

At any point in time, one’s belief system is a theoretical “point” in this three-dimensional space. Ideally, one wants to move that point toward the head of the arrow.

Number of beliefs

Generally, the greater the number of individual beliefs comprising a belief system, the more truth-conducive the belief system is. You increase the number of your beliefs by exposing yourself to more experiences. Most of our marketing experiences come from “doing marketing” over the course of our marketing careers. But other “experiences” also include continuing education through a college or university, attending conferences, and reading marketing-related materials such as books, journals, and magazines. For example, I hope that by reading this book you form the belief that applying scientific reasoning to business decisions increases the probability that your decisions will lead to successful outcomes.

Variety of Sources

Marketing myopia can be caused by increasing the number of your beliefs without expanding the variety of sources on which they are based. In part, this comes about by organizations not investing in (or at least encouraging) their marketing managers’ continuing education. Nevertheless, we all need to take some responsibility in seeking to expand our own knowledge of marketing.

In this light, keeping up with the field of marketing can be challenging. Over the past 10 years, many fields of research—some not traditionally linked to marketing per se—have significantly influenced how marketing and marketing research is done. Consider the effects of the following fields on marketing:

• Behavioral economics (BE): It is the “study of psychology as it relates to the economic decision making processes of individuals and institutions.”9 The field of BE has become quite popular as a result of bestselling books such as Dan Ariely’s Predictably Irrational and Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner’s Freakonomics.

◦ Here’s an example of applying BE discussed in a recent McKinsey publication: Offering consumers too many options, say at the point of purchase, can result in generating “choice overload,” which makes consumers less likely to purchase a product. Additionally, it can cause a “negative halo,” in which consumers “have a heightened awareness that every option requires you to forgo desirable features available in some other product. Reducing the number of options makes people likelier not only to reach a decision but also to feel more satisfied with their choice.”10

• Neuromarketing (NM): “…a new field of marketing which uses medical technologies such as fMRI to study the brain’s responses to marketing stimuli. Researchers use the fMRI to measure changes in activity in parts of the brain and to learn why consumers make the decisions they do, and what part of the brain is telling them to do it…”11 An example: Showing consumers using your product in an advertisement—as opposed to merely showing a static picture of it—can stimulate the brain’s mirror neurons, which are involved in our directly mimicking or experiencing vicariously the actions of others. As Martin Lindstrom says in his book, buy · ology, thinking about “other people’s buying behavior affects our shopping experience, and ultimately influences our purchasing decisions.”12

• Anthropology: “The science that deals with the origins, physical and cultural development, biological characteristics, and social customs and beliefs of humankind.”13 From this field, marketers have borrowed a novel research tool called ethnography. “Simply, ethnography is the study of behavior in its naturally occurring context,” says Richard Elliott, professor of marketing and consumer research at Exeter University in the United Kingdom.14 Many years ago, a national luggage manufacturer conducted an ethnographic research study in which it viewed consumers shopping for luggage in a department store. A major finding from this research was that consumers were not standing in front of their point-of-sale (POS) placards long enough to read the product information on them. Consequently, the company redesigned their POS placards to contain less information.

• Psychology: “The science of the mind or mental states and processes.”15 For example, the psychology of color is a fascinating field and can perhaps explain why you have noticed how often the President of the United States wears a blue colored tie. Certain shades of blue have come to be associated with “steadfastness, dependability, wisdom, and loyalty.”16 There are even a few journals dedicated to psychology and marketing—Journal of Consumer Psychology and Psychology and Marketing among them. One recent article in the latter examines how “green consumption”—the tendency of some consumers to prefer environmentally friendly brands—has been shown to influence brand loyalty.17

Coherent Belief Systems Help Us Market Better

Broadening your marketing belief system by exposing yourself to these fields can significantly influence your ability to make better marketing decisions For instance, a marketer may have 20 years of marketing experience, but if the variety of sources from which those experiences are drawn is relatively limited, the decisions informed by them may be ineffective For example, between the following two marketers in Table 9.1, who do you feel is more likely to possess the more robust, coherent belief system?

Table 9.1 Who Possesses the More Coherent Belief System? (All other factors held constant)

|

Marketer A |

Marketer B |

|

• 20 years of marketing experience • Held two marketing positions • Reads little outside of the newspaper |

• 10 years of marketing experience • Held two marketing positions • Has read many books on marketing, advertising, BE, and consumer psychology • Has taken an executive course on marketing strategy |

Marketer B is more likely to possess the more coherent belief system because he has more beliefs derived from a greater variety of relevant sources. Marketer B will make more effective marketing decisions over the long run. The implications of the above discussion are clear:

Building a more coherent marketing belief system requires marketers to expand their knowledge beyond the traditional introduction-to-marketing textbook. The best marketers will possess a variety of career experiences, and be well read across diverse fields.

Validity

Possessing a great many marketing beliefs, derived from a wide range of experiences is not, by itself, enough to develop a relatively coherent belief system. At least some of your beliefs—the more the better, actually—need some degree of empirical support. This empirical support can come from research either that your organization has undertaken, or that other reputable researchers have conducted.

Of course, it’s not that easy, is it? Who is one to believe? That’s why I said earlier that developing a coherent marketing belief system is a journey, not a destination. There…is…no…silver…bullet. You may want to remember this the next time you come across a book or article that promises a quick, easy-to-use transformative method to improve your marketing skills. There simply aren’t any.

How to Strengthen Coherence

How, then, should you go about strengthening the validity of your marketing belief system—without having to get several PhDs in the process? Here are three ways:

1. Improve your critical thinking skills. Reading this book, especially the next chapter on logic, will help you develop your critical thinking skills. The “Additional Readings” section suggests other critical thinking resources you might want to consider.

2. Develop and, ideally, test your own marketing beliefs. As I’ve said, this is not a marketing research textbook, so I’m not going to give you a primer on how to test your beliefs and theories empirically, but I will discuss at length how to develop theories in Chapter 12.

3. Read more. Become more familiar with the marketing literature and the literature of other fields (e.g., BE, psychology, and neuromarketing) that are making potentially valuable contributions to marketing. The last chapter of this book gives you a suggested reading list. I have a personal favorite, Marketing Management magazine, published by the American Marketing Association.

Closing Comments on “Coherence”

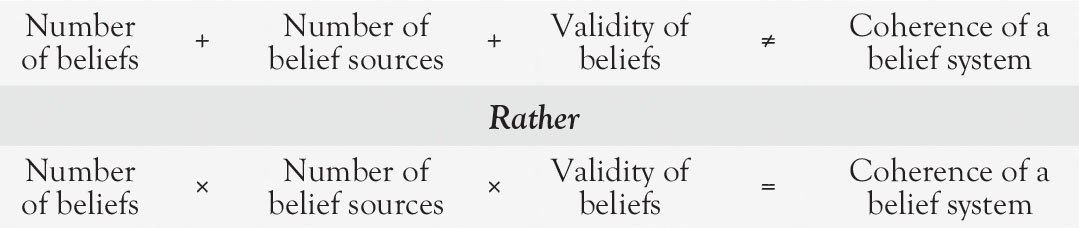

A marketing belief system’s coherence does not reside in an additive relationship among the three major components comprising it, but rather in their multiplicative effects, as shown below.

A weakness in any one component can severely compromise the validity of the belief system overall, and the marketing actions that emanate from it. For example, consider Wal-Mart. You will recall that one property of a coherent marketing belief system is clarity—how clearly and correctly do we define our terms that comprise our beliefs? Incorrect definitions of terms such as market segments, product, and value can keep marketers from understanding what truly motivates consumers.

Wal-Mart’s decade-long decline in US annual comparable-store sales is a consequence of a major misstep concerning how the company defined its customer. Senior executives held the belief that Wal-Mart could broaden its brand equity into organic foods, fashionable jeans, and dress up its store with wider aisles, less clutter, and shelf space. The result was reduced sales and frustrated vendors.18 According to The Wall Street Journal’s Miguel Bustillo, “The Bentonville, Ark., chain’s up-market push, which began before the recession, succeeded in attracting some well-heeled customers, but at great cost. Wal-Mart lost its iron grip on US households earning less than $70,000 a year—which made up 68% of its domestic business—to other discounters.” Andy Baron, a Wal-Mart executive vice president, said “Clearly, we’ve lost some of our focus on what I would call the core customer. You might say, in short, that we were trying to be something that maybe we’re not.” In other words, the belief that Wal-Mart could broaden the definition of its customer base was not justified. A more coherent marketing belief system might have shown Wall-Mart the apparent error of its ways.

As one travels up the arrow in Figure 9.1, the likelihood that one’s belief system is truth-conducive increases. Indeed, it is the coherence theory of empirical justification that serves as the basis for the epistemic justification of beliefs in all science.

So why should marketers not subscribe to it?

Chapter Takeaways

1. A belief is what we accept to be true, in varying degrees of probability. We call a collection of related beliefs a “belief system.” Your marketing belief system informs your marketing decisions. Note: as discussed in Chapter 5 Worldviews, the philosophy of science literature sometimes refers to belief systems as “worldviews.”

2. Most scientists and philosophers agree that we do not have access to absolute, infallible truth. So, what’s our next best option? We need to do the best we can to justify the beliefs and the belief systems on which marketing decisions are made.

3. The coherence theory of empirical justification (“coherence”) is a tool that we can borrow from epistemology to help us justify the belief systems that inform marketing decision making.

4. Important properties of marketing belief systems are that they are:

a. Logically connected

b. Empirically based

c. Mathematically and empirically sound

d. Clearly articulated (e.g., minimize ambiguity and vagueness of beliefs and definitions).

5. The more coherent a belief system is, the more truth-conducive it is.

6. You can strengthen the coherence of your marketing belief system by expanding the number of beliefs it contains, the variety of sources from which these beliefs are derived, and the empirical validity of the beliefs that make up the system. How can you go about doing this?

a. Improve your critical thinking skills

b. Develop and, ideally, test your own marketing beliefs

c. Read more—increase your familiarity with the marketing literature and the literature of other related fields such as BE, psychology, and neuromarketing, as well as general reading about consumers and trends.

7. This task is a journey, not a destination. There are no silver bullets.