Steps 10 Through 14

23- to 25-year-olds with bachelor’s degrees make $12,000 more than high school graduates but by age 50, the gap has grown to $46,500. When we look at lifetime earnings . . . the total premium is $570,000 for a bachelor’s degree and $170,000 for an associate’s degree.

—Brookings Institution

Key Points

• Although you certainly want a college education that will prepare you to get your first job, it’s more important to prepare for success—not just in that job, but in your entire career and your life.

• Selection of your major is at least as important as your selection of a school in getting a job that makes use of your education.

• Healthcare, engineering, computer science, and business majors are most likely to land jobs that require a degree and that are related to their majors.

• Employers are generally more interested in graduates with cognitive, communication, and work skills than in domain-specific content knowledge.

• Even if you’re in a professional or preprofessional major, be sure to include a healthy dose of liberal arts classes.

• Although some little-known colleges provide the best returns on your education investments, some elite private universities may offer some of the best college bargains.

College had been an integral part of the American Dream: A veritable ticket to a good job and an upper middle class lifestyle. To some graduates, it is increasingly becoming part of the American nightmare: underemployment or even unemployment, combined with big debts. Former Secretary of Education Bill Bennett, for example, claims that only 57 percent of adults now believe a college degree is worth it, compared with 83 percent in 2008.1

But, for better or worse, a college degree is becoming the new high school degree. A growing number of employers now look for applicants with degrees, even for jobs that didn’t traditionally require them. Even for jobs where they are not actually required, many employers will almost reflexively choose an applicant with a degree over one without one. This has led to rapid growth in college enrollment (although there was a slight decline in 2012). Even though a pitifully high 36 percent of students who begin at a four-year college don’t graduate within six years, a record percentage of young adults (38 percent of those between 25 and 34) now hold some type of postsecondary degree.2

The good news for aspiring graduates is that this is nowhere near sufficient to address projected demand. Although close to half of all recent college graduates either can’t get jobs or can’t get ones that require a degree, a Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce study states that 63 percent3 of all U.S. jobs will require some form of postsecondary education by the year 2018. Although the skills requirements for new jobs is certainly expanding, some of this new demand will likely come from the same type of “job inflation” that has already affected college grades. We are already seeing employers demanding college degrees for jobs that have not traditionally required them. Unfortunately, few of these jobs pay college-level wages or provide college-level career paths.

But, while a four-year degree (or increasingly even a graduate degree) is increasingly becoming a de facto requirement for a growing number of jobs, this does not, as suggested in Chapter 7, necessarily mean that college is right for you. And it absolutely does not mean that you can’t get a good job without a degree. In fact, as discussed previously, the number of occupations that require certificates and associate degrees are growing more rapidly—and some of these offer better pay and probably more stable careers than do those that at least nominally require degrees. And there are now many more opportunities for getting solid non-four-year postsecondary education than has been the case in the past.

The educational and job opportunities for these less traditional postsecondary education and training programs are discussed in detail in Chapter 9. This chapter looks specifically at the factors you must consider if you are among the growing number of high school grads that has decided that college is right for you. It looks at everything from how to select the type of college and the specific school that is best suited to your needs, what you should look for—and even demand—from your professors and your courses, the major and minors that are most likely to result in good jobs, and how to deal with the skyrocketing costs of getting a degree.

Finding the School that’s Right for You

Colleges and universities have long been the pride of the U.S. educational system. U.S. institutions perpetually dominate ranks of the world’s best universities, with 7 of the world’s top 10 and 43 of the top 100 in U.S. News current rankings.4 This being said, overseas schools are making big gains. European (especially UK), Canadian, and Australian schools have long been well regarded and a growing number of Asian schools are now climbing in the global rankings.

Now that a global (and especially Asian) perspective is so important in so many fields, U.S. applicants should increasingly look to such schools for at least part of their education. This may include anything from full-time enrollment in a degree program to participation in an exchange program to some form of work–study experience. It should ideally be in a country in which you have a deep interest, one that is likely to be important in the field in which you hope to build a career, or one with particularly strong growth prospects, such as China, India, or many other countries in southeast Asia, Africa, or Latin America. If in doubt, you can bet that China will play a growing role in your field, almost regardless of what that field may be.

That being said, what should you look for in a college—and how do you identify the colleges that can best provide it and those that will be the best fit for you?

As a general rule, you should probably lean toward the most highly rated school in the field in which you plan to major and that you can get into—and, as will be discussed later, that you can afford.

As a general rule, you should probably lean toward the most highly rated school in the field in which you plan to major that you can get into—and that you can afford.

Why? First, going to a school that doesn’t fully challenge you can lead you to disengage or even drop out. Second, many employers place great weight on the quality of the school. Not necessarily because they deliver better education, but because selective and highly selective schools already provide a good first-level filtering of candidates for some of the characteristics that many companies value. In fact, one recruiter, who was asked who was the most important reference for a potential employee, only half-jokingly claimed that it was the college admissions officer! Indeed, Ivy League social sciences and humanities graduates often get more and better job offers than do graduates of lower tier business schools with better grades.

How do you find the most selective, most highly rated schools in your field of study? While there are many ways of assessing and ranking colleges, counselors can be a great help. U.S. News and World Report rankings are also widely followed, although not always for the best of reasons.5

Having said this, you need a college that will address not just your academic needs but also your social and emotional needs. Do you, for example:

• Want an education that will specifically prepare you for a job, one that will prepare you for graduate or professional school, or one in which you can learn a broad range of life skills (see Chapter 3. Examples of these life skills include learning how to learn and loving to learn, critical and innovative thinking skills, social and oral and written communication, adaptability and persistence, and how to deal with and learn from failure and rejection;

• Prefer a liberal arts college or one that offers a broad and deep range of courses in your particular area of interest (recognizing that your interests may well change through your college career);

• Feel more comfortable in a large school or a smaller one, in a large city or a relatively remote campus; or

• Want to or have to stay near home (such as to care for family, to work, or to reduce expenses by living at home) or would you prefer to “escape” your home town and live with your peers.

Beyond that, there are a number of factors to look to in deciding whether a particular school will provide an environment that will allow you to address your specific goals—academic, social, extracurricular, and career. Your chosen school should deliver all of this at a cost that will not break the bank or plunge you or your parents deeply into debt.

Although there is, as discussed below, an intense debate as to most important missions of colleges, students and parents, for better or worse, appear to be in growing agreement as to what they believe is important. According to Eduventure’s 2013 College Bound Market Update, career preparation is now the single most important criterion that applicants and their parents look to in selecting a college.6 This is followed, in declining order, by core academics, academic environment, affordability, and social environment.

Selecting a School

This very pragmatic focus on college’s role in preparing students for a career places many schools in an uncomfortable position. Most have held themselves to loftier objectives, such as helping students learn about themselves and the world; critical thinking and complex analysis skills; and especially a love of learning.

They’re understandably reluctant to change their curriculum based on what they perceive as a “transitory need for a particular skill.” They are particularly reluctant to turn their institutions of higher learning into “vocational schools.” And even if they wanted to, how many university professors (outside of business or some science and engineering fields) are close enough to the private sector to really understand and teach the type of skills that companies will need over the next 5 to 10 years?

As a former liberal arts student (philosophy and economics), I see huge value in a traditional liberal arts education. I mourn the decline in social science and humanities in favor of “practical” undergraduate majors and hope that the vast majority of students will understand and take full advantage of the long-term value that can be gained from an interdisciplinary liberal arts education.

Having said this, I believe that schools can and must play a central role in helping their students prepare for a fulfilling career (at least partially to ensure that alumni will be able to financially support and refer potential students to their alma mater). Luckily, a growing number of such schools are getting the message and are increasingly integrating career development into their missions. Wake Forest University, for example, attracted career officers from more than 70 universities to a three-day conference titled “Rethinking Success: From the Liberal Arts to Careers in the 21st century.”

If you are looking for a college that will help you prepare for both life and a career, you should look especially to schools that blend theoretical and applied learning, such as by:

• Adapting their academic programs to emphasize real-world applications, as through labs and practicums;

• Integrating IT skills (such as programming, research techniques, and social media) and math (especially statistics and analytics) into virtually every area of study;

• Encouraging interdisciplinary research and course coordination among diverse, but complementary areas of study (such as combining economics and psychology, architecture and urban studies, transportation and mechanical engineering, or biology and chemistry—or any of the above with math and/or information technology);

• Working more closely with the private sector to support and develop curricula around skills that businesses require, such as by inviting companies to engage with professors in joint research projects and in delivering lectures, by developing case studies across all types of disciplines (in addition to in business schools), and by arranging substantive internships;

• Engaging career services offices, faculty, alumni, and prospective employers in sponsoring web conferences and seminars that discuss career options for different disciplines; and

• Providing proactive coaching to help students design programs that integrate career and academic goals, suggest relevant internships and companies that are looking for particular backgrounds, and track progress.

Some more practically focused colleges, such as Babson, Olin, and Harvey Mudd Colleges, have been doing this for years. Meanwhile, a growing number of liberal arts colleges are taking a more integrated approach to helping students think about and plan for their careers. For example:

• Clark University’s Liberal Education and Effective Practice (LEEP) is a four-year program that helps students think through their career goals, integrate coursework with career-preparation workshops and alumni mentorships, and plan internships and research opportunities;

• Wake Forest offers a minor in innovation, creativity, and entrepreneurship (which is now the university’s most popular) that is designed to be integrated with a liberal arts major.

Even the University of Chicago, one of the most academic of all liberal arts colleges (85 percent of whose graduates go on to graduate school), is taking an increasingly comprehensive approach to helping its undergraduate students prepare for careers.7 For example, its Career Advancement Office’s:

• Career Exploration workshops encourage students to consider what career options are of interest to them;

• Steps to Success program helps first-year students think about potential careers, craft resumes around these objectives, and make the most effective use of their summer opportunities and line up meaningful internships;

• Major Madness series helps second-year students conduct personal inventories, think about career paths, and understand the role of different majors in preparing for these paths;

• Taking the Next Step conferences help second- and third-year students explore postgraduation options and meet with alumni who have pursued careers in their areas; and

• UChicago Careers programs help students explore opportunities in specific areas, such as education, public service, healthcare, law, and business.

But, when evaluating colleges, you must consider much more than their ability to prepare you for and help you get your first job. You should look for a college in which you will be comfortable, one that will continually challenge you, and one that will prepare you for many potential careers (including some of which you have never thought of, or even have not yet been invented). You must also look for a college at which you will learn long-term career and life skills (see Chapter 3 and provide you with a varied social experience, as well as one that will prepare you for your first job. Depending on how you learn, you may also want to assess the types of learning options they offer. For example:

• What percentage and types of courses are taught via lecture, rather than in smaller, collaborative discussion-based classes;

• Does the school provide options for taking some courses online, rather than in class; and

• What type of student-to-student and student-to-teacher interaction is offered?

For a college that will help you prepare for both life and a career, you should look to schools that blend theoretical and applied learning, encourage interdisciplinary education, offer proactive career coaching and that teach in ways that you best learn.

Of Majors, Job Offers, and Starting Salaries

In an ideal world, you would major in whichever field you have the greatest interest and find to be most intellectually challenging, and then chose a job that will give you an opportunity to apply your knowledge and skills to the type of real-world problems that you find to be most interesting.

Needless to say, this is not an ideal world. Graduates who hope that businesses will recruit them for their raw potential and then train them on the specific requirements for the jobs are usually disappointed. True, a number of employers used to hire for potential and you will occasionally still find a few such companies. Most companies, however, have reduced their training programs and are now looking for people with the technical (and often the practical) skills required to be productive from day one—in addition to offering long-term growth potential. Although some companies anticipate rebuilding at least some of their training programs, don’t expect miracles.

Despite my whole-hearted belief in the value of a liberal education (with specialization coming on the job or in graduate school), this unfortunately appears to be becoming a luxury for all except for those who graduate from the most selective of schools, or for those who plan to go to graduate or professional school.

This being said, all too many students forgo both the opportunity to use college as a means of developing life skills, and of developing job skills. They totally shortchange their college experiences by forgoing both the long-term value of a challenging liberal education and the practical value of a career-focused discipline in favor of a major and course schedule that won’t impinge on their social lives. They select majors and courses that require the least work and promise the highest grades, rather than those that offer the best learning opportunities.

Do not succumb to these temptations! Such choices are likely to come back to bite you in a market where jobs are scarce. After all according to an Associate Press-sponsored analysis8 of 2011 Labor Department data:

In the last year [college graduates] were more likely to be employed as waiters, waitresses, bartenders, and food-service helpers than as engineers, physicists, chemists, and mathematicians combined (100,000 versus 90,000). There were more [graduates] working in office-related jobs, such as receptionist or payroll clerk, than in all computer professional jobs (163,000 versus 100,000). More were employed as cashiers, retail clerks, and customer representatives than engineers (125,000 versus 80,000).

Why? One of the primary reasons is that, as discussed in Chapter 2, far more jobs are being created in lower skill, lower pay occupations than in higher skill, higher pay fields. Only one of the 20 occupations the BLS expects to have the greatest number of openings over the next decade explicitly requires any postsecondary degree at all.9 That occupation, registered nurses, who require a minimum of an associate’s degree. In fact, only eight of those occupations that are expected to generate 50,000 more jobs explicitly require a bachelor’s degree or higher.10

Just as jobs that require a college degree are less numerous than those that do not, some also pay less. Although those who earn bachelor degrees do, on average, earn more than those with high school diplomas or associate degrees, there are many exceptions. As shown in a 2012 Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce study, The College Payoff, 14 percent of people with a high school diploma make at least as much as the median earnings of those with a bachelor’s degree, and 17 percent of people with a bachelor’s degree make more than the median earnings of those with a professional degree.11

Not surprisingly, many recent graduates have had second-thoughts about their choices of majors. A 2013 Accenture survey, for example, found that 48 percent of 2011/2012 graduates said that they would have fared better in the job market had they chosen a different major.12 Indeed, a 2012 report by the John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development found that 37 percent wish they had been more careful in selecting their major, or would have chosen a different major.13 Of these:

• Forty-one percent would have chosen a professional major, like communication, education, nursing, or social work;

• Twenty-nine percent would have chosen a STEM major;

• Seventeen percent would have selected business; and

• Only 11 percent would have selected social science or the humanities.

48 percent of 2011/2012 graduates believe that they would have fared better in the job market had they chosen a different major.

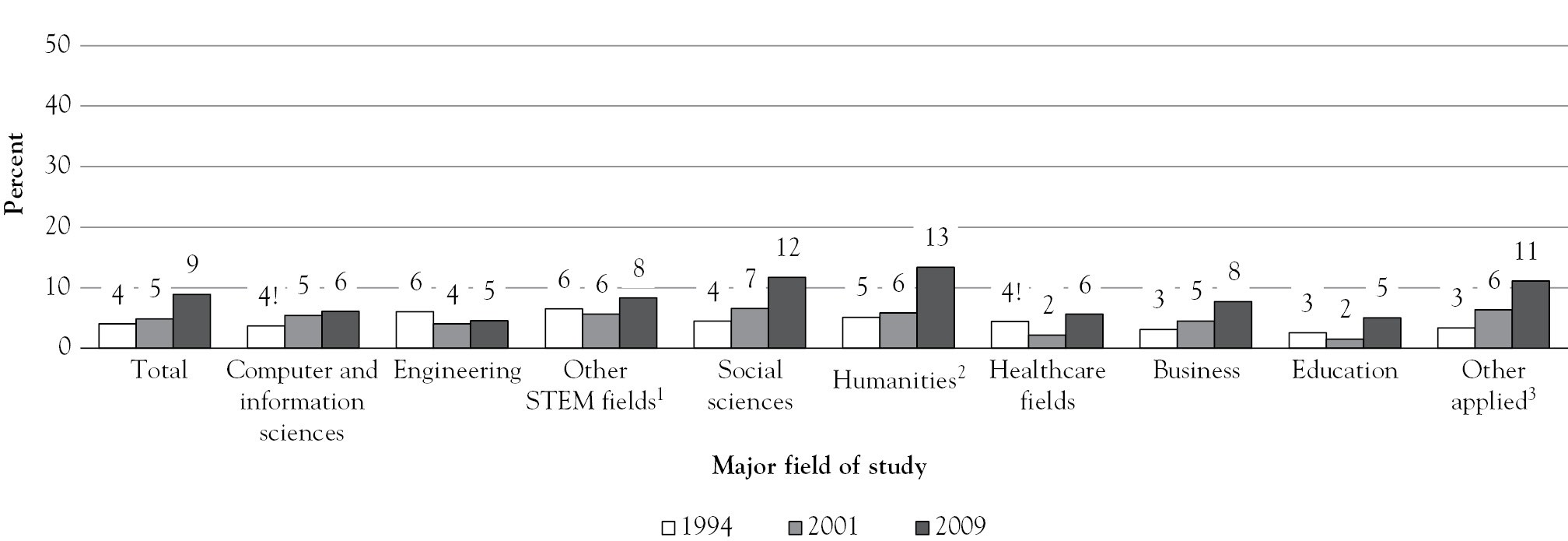

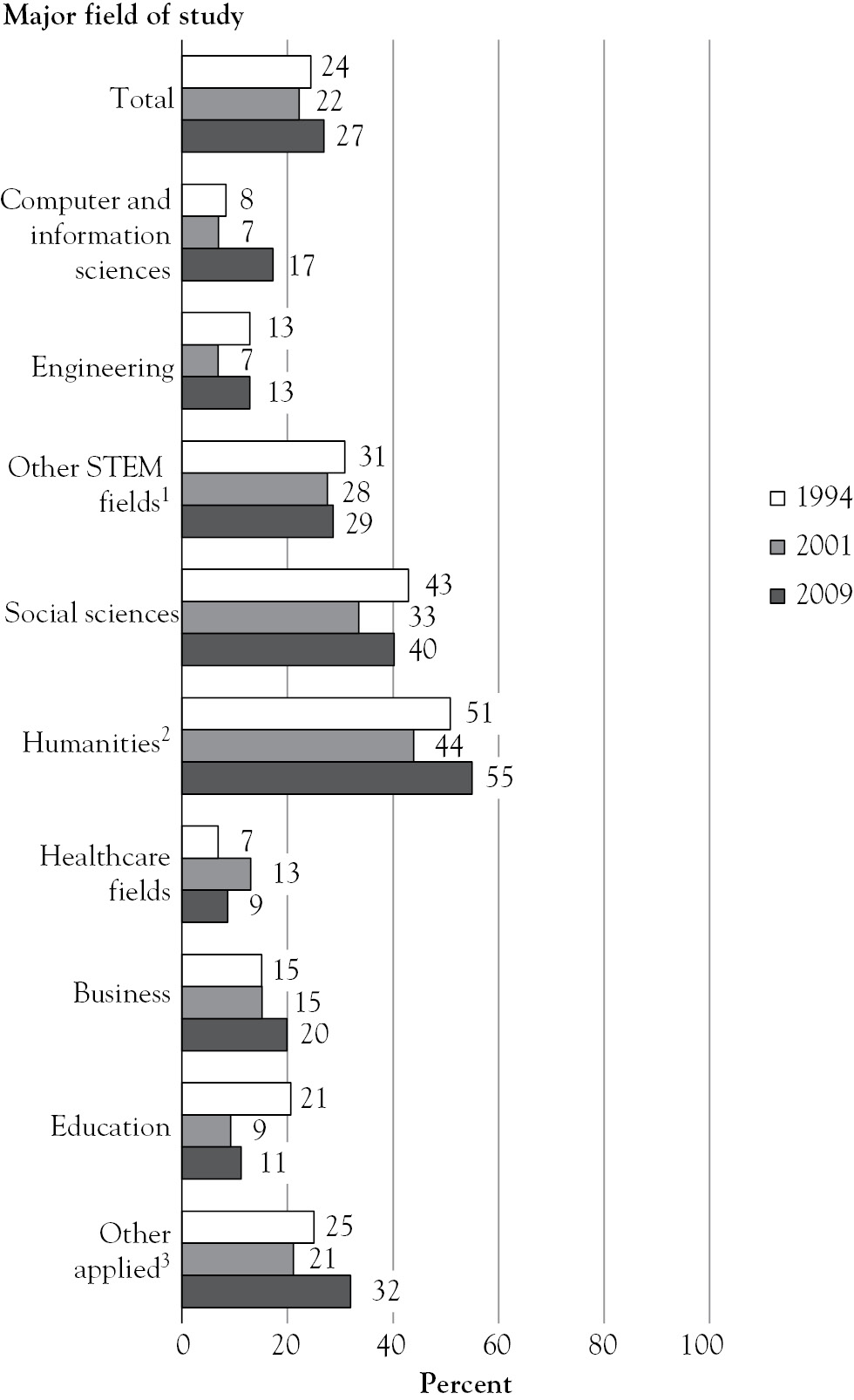

Although this choice of majors is certainly a big setback for those (including me) who find huge value in a liberal, ideas-centered education, it is certainly pragmatic. As shown in Figure 8.1, well over 90 percent of those 2007 and 2008 undergraduates who majored in healthcare, education, engineering, computer science, and business landed jobs. Humanities and social sciences graduates were at the bottom of the list with unemployment rates of 13 percent and 12 percent, respectively. And, as shown in Figure 8.2, liberal arts majors were also far less likely to get jobs that were related to their majors.

Figure 8.1 Unemployment and major field of study

Source: Graduation (n.d.), Figure 5, p. 8.

Figure 8.2 Job unrelated to major and major field of study

Source: Graduation (n.d.), Figure 6, p. 9.

Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce provides a much more granular breakout for 2010, showing unemployment rates, earnings, and popularity among students for each of 173 different majors.14 (See also the Wall Street Journal concise overview of these findings.)15 Although sample sizes for some of the less popular majors are undoubtedly small, and must be taken with the proverbial grain of salt, unemployment rates suggest wide variations among disciplines in the same general field. Engineering unemployment rates, for example, range from zero for geological engineering to 9.2 percent for industrial management. Those in education, from zero for educational administration to 10 percent for educational psychology.

Advantage: STEM

Some majors offer not just better employment prospects than others but also more choices in the type of job, field, and industry in which you work. A separate Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce report, appropriately named STEM, provides a comprehensive overview of all STEM fields, from definitions to explanation of different types of occupations, to hiring trends, and almost everything you may want to know about STEM wages.16

The study also examines the offers received by—in addition to the jobs actually taken by—science and engineering grads.17 It finds that those who major in these fields not only receive more job offers than those in other fields, but they also have a greater choice of fields in which to work. Fewer than half of STEM graduates, in fact, end up taking jobs in the field in which they majored. Employers look to them to, and grads often choose to employ their skills in jobs that use the skills from, but are not specifically in their field—jobs in areas including sales, marketing, or finance. Why would STEM graduates choose to work in another field? Many may see them as offering more opportunities for social engagement or for offering more varied career paths.

Although the differences in employment prospects among majors are great, the differences in salaries are even greater—much greater. While salary should not be a primary factor in selecting a career or a major (see Chapter 10 for a fuller discussion), it does have to be considered. And, of the 173 majors listed in the Georgetown survey, all of the top 10 bachelors’ degree majors yielding the highest median salary were in STEM fields. These were led by petroleum engineering, with a median salary of $120,000—and $189,000 at the 75th percentile.18 Psychologists occupied the opposite end of the salary spectrum, with counseling psychologists earning $21,000 at the 25th and $42,000 at the 75th percentiles. These salaries were even lower than for oft-maligned humanities degrees, such as visual arts and theology.19

Payscale generally confirms the salary premiums that STEM grads can command. Its 2013 to 2014 College Salary Report20 shows that all of the 10 top-paying majors21 (all with starting salaries above $50,000 and average mid-career salaries above $100,000) and 37 of the top 40 (with starting salaries ranging from $40,000 to $100,000) were in STEM-related fields. (While a few of these, such as economics and construction management, are not strictly STEM professions, they rely heavily on math.) Only three of these top-paying majors do not have significant STEM requirements: government, international business, and international relations.

Not only do engineering and science grads in most majors get more and more varied job offers, have less unemployment, and earn higher salaries than bachelor degree grads in other fields, they also, according to the Georgetown report, earn more than those with advanced degrees in other fields. According to the report:

Sixty-five percent of students earning bachelor’s degrees in science or engineering fields earn more than master’s-degree holders in nonscience fields. And 47 percent of bachelors-degree holders in science fields earn more than those holding doctorates in other fields.22

STEM degrees also age well, with the wage premium for STEM-educated workers actually growing over time.23 And this is true, both upon graduation and over a lifetime, regardless of whether you actually work in a STEM profession.24

STEM majors typically get more and more varied job offers, have less unemployment, and earn higher salaries than bachelor degree grads in other fields.

However, by the time you reach the masters and doctor or doctorate levels, healthcare (which requires deep science knowledge) and business (which is increasingly math-intensive), tend to command higher premiums than engineering and computer backgrounds.25

As if the competition to hire and reward for STEM skills is not heated enough, both seem to be amping up. As discussed in a 2012 Wall Street Journal article, a growing number of technology firms are targeting premier computer science and software engineering students well before they graduate—using $100,000 to $200,000 packages to persuade them to drop out of college (or at least to commit to the company upon graduation).26 And this does not even count the 17-year old British high school student that Yahoo just hired as part of its $30 million acquisition of his small software company!27 Google, in particular, has already posted 400 student ambassadors (with plans for more than 1,000) at top universities to identify and recruit prime talent.

If a degree in one of these STEM fields is valuable, combining majors in two fields—especially two STEM fields—can produce even greater benefits, not only in employment and salary but also in flexibility as to the industry and field in which you work, and in the long-term demand for your services. Or you could get the best of both worlds in terms of employment prospects, flexibility, and compensation, by combining a STEM major with an MBA. A broad range of dual major, or major and graduate degree combinations are specifically discussed in the following sections.

Comparing Fields of Study

Let’s look at the demands for three broad classes of majors in a bit more detail—STEM, business, and liberal arts.

STEM

The vast majority of students—the 88 percent that do not graduate with STEM majors—are probably getting pretty tired of hearing about the competition for recruiting STEM graduates, and the multiple job offers, high salaries, and lavish benefits that are showered upon them. You had better get used to it.

The popularity and high salaries for STEM graduates should come as no surprise. The surprise is that, with all these rewards, only 12 percent of college students choose STEM majors. This is not all for lack of interest. As I discussed in my December 2011 blog, Expanding the Ranks of STEM Professionals, 30 percent of all incoming 2009 college freshman planned to major in one of the STEM fields.28 Unfortunately, many of those students who aspire to a STEM career lack sufficient high school backgrounds. Fewer still are prepared for the workloads required of a STEM major. The majority end up switching to less demanding majors.

But not all STEM graduates necessarily share in this bounty. Most STEM fields, especially in most types of engineering, software development, and many of the physical sciences, offer plenty of opportunities for bachelor-level grads. Some, however, such as general science are a bit too broad, and others like animal and neuroscience offer more opportunities for those with advanced degrees. Of all the STEM majors, some form of computer science is probably the most versatile and promising major. At least Stanford undergrads seem to think so, since the school’s redesigned, more interdisciplinary major is now the undergraduate school’s most popular.29

Business

Business is, overwhelmingly, the single most popular undergraduate discipline, accounting for 22 percent of all 2010/2011 bachelor degrees.30 This is somewhat understandable given parents’ and students’ growing desire for “marketable skills.” And it can certainly pay off, especially if the degree is in a high-demand quantitative field such as finance, accounting, auditing, and supply-chain management, or in some marketing fields, such as e-commerce.

Unfortunately, many business grads, especially those from less selective schools and with less focused or demanded majors, find that they are less marketable than they anticipated. One reason is that a growing number of companies have begun to question the value of an undergraduate business degree.

As explained in the Carnegie Foundation report, “Rethinking Undergraduate Business Education: Liberal Learning for the Profession,” undergraduate business education is often more narrow (focusing on technical mastery of discrete segments of knowledge) and less intellectually rigorous than many liberal arts (much less STEM) curricula.31 Business courses often lack the type of long essays and class debates that help to develop critical thinking and problem solving and “fail to challenge students to question assumptions, think creatively, or to understand the place of business in larger institutional contexts.”

Although business degrees can result in good jobs (especially in high-demand quantitative fields such as finance, accounting and supply-chain management), a growing number of employers view business curricula as too narrow and insufficiently rigorous.

Given this, a number of those premier (not to speak of the best paying) companies, such as those in consulting, technology, and finance that do recruit bachelor-level graduates, are increasingly targeting candidates with broader, more rigorous academic backgrounds, such as in STEM, economics, and even English. They often find it easier to teach these graduates the required content, than to teach critical thinking and problem solving skills to business graduates.

A number of undergraduate business schools are responding by requiring or strongly encouraging their students to incorporate liberal arts courses into their business curriculum, to integrate historical, psychological, ethical, and sustainability considerations into traditional courses; providing more global perspectives; and by requiring more and deeper written analyses. Even if your school does not require such courses, you should incorporate them into your own program.

Healthcare

Demand is surging and will continue to do so for anyone with an associate degree or higher in virtually any healthcare discipline. Demand and compensation will be particularly strong for nurses (especially those with bachelor degrees or higher) and especially for those with masters, doctor, and doctorate degrees in virtually all segments.

Most of these positions require a minimum of a bachelor of science degree in your target specialty, and most, as mentioned, require some type of advanced degree and state certification. Information on the educational requirements, responsibilities, career opportunities, and salaries for all types of occupations is available in a BLS report32 on healthcare occupations and on the healthcare sections of sites including Bureau of Labor Statistics,33 O*Net,34 and WorldWideLearn.35

Careers in healthcare, however, go way beyond those for the actual care providers. Hospitals and HMOs, like any other large organization, also need managers, accountants, IT and human resource professionals, marketers, lawyers, and all types of support workers. Although many of these jobs don’t require specific knowledge of the industry, having a specialty or experience in areas such as medical records management for accountants and IT managers, or regulatory compliance for lawyers can provide advantages in getting jobs and in commanding higher salaries. There are, of course, also hundreds of occupations outside, but that work closely with healthcare providers. These include industries such as insurance, pharmaceuticals, and medical electronics.

Liberal Arts

We all know that those with four-year degrees in liberal arts find it more difficult to find a job out of school, are more likely to be unemployed—and especially underemployed—and earn less money than those with preprofessional degrees. Although graduates of elite colleges may get good jobs right out of school, those from less selective schools often end up in lower paying (albeit potentially intrinsically rewarding) jobs such as counselors, social and community service workers, customer service representatives, and in any of the hundreds of professions that do not require college degrees, and do not offer particularly compelling career paths.

A comprehensive 2013 study by The Association of American Colleges and Universities, meanwhile, shows that it takes most liberal arts graduates longer to get jobs out of school and they typically earn about $5,000 less than graduates with professional or pre professional programs.36 When they do get jobs, however, employers are often pleased with the results, claiming that their broad backgrounds allow them to think critically and work effectively in diverse teams. This may help these graduates advance more rapidly than—and close at least part of the initial salary gap with—business and healthcare (albeit not STEM) undergraduates over time.

Some liberal arts graduates, in fact, end up eventually overtaking salaries of those with business and healthcare (but again, not STEM) degrees. These, however, are primarily among the roughly 40 percent of all liberal arts undergraduates that end up getting advanced degrees.

It generally takes liberal arts graduates longer to get jobs out of school and they typically earn less than graduates of professional or pre-professional programs. Their intellectual preparation, however, may end up resulting in faster promotions and eventually, even higher salaries.

The lesson from this is not necessarily to shun liberal arts. The perspective and skills derived from a challenging, multidisciplinary liberal education can yield big dividends, in both your professional and personal life. The lesson is that you must be able to show employers that you can make immediate contributions to their business, in addition to providing long-term growth potential. You can do this either by getting a master’s degree in a relevant field or by having and demonstrating strong skills in an area in which large numbers of employers always need help, such as programming in popular languages like Python, Java, C++, and Ruby. (See Chapter 9 for a discussion of the growing options for college graduates to learn these and other career-enhancing skills.)

Selecting Your Courses, Majors, and Minors

Career preparation should certainly be an important consideration in selecting courses, major, and minors. It probably, however, shouldn’t be your first, much less your only consideration.

For example, if you enter college with a very good idea of your dream and safety careers, you may be inclined to quickly declare your major and to sign up for as many courses as possible in these fields. Bad plan.

Constructing an entire college program around the requirements for a specific career can do more to limit your career, than to enable it. It can lock you into a field in which job prospects are limited by the time you graduate (not to speak of by the time you are ready to retire), or in which you may lose interest. Meanwhile, some fields may focus so heavily on teaching the “tools of the trade” that they deemphasize development of the type of high-level thinking, conceptual and communication skills that will be required to succeed in any high-skill job. Most importantly, however, the first few years of college provide some of the greatest opportunities for discovery that you will experience in your life.

You should absolutely take a few courses in your target fields over these two years. These can help you decide if they are really the areas in which you want to dedicate your career (or at least your first couple of jobs), provide a solid foundation for deeper studies in this area, and allow you to experience and meet professors with whom you will want to engage later in your studies. Your primary objective for these first two years, however, should be to experience as many different fields as possible. Some should certainly be focused around core skills that will be required in any career (introductory computer science, statistics, public speaking, persuasive writing, and so forth). Others, regardless of the field, that will give you experience in skills such as critical reading, creative thinking, logical writing, and teamwork.

As for subject area, go for fields in which you have an interest, a curiosity, or that sound like they may have the potential for engaging you. Most importantly, look for those courses—regardless of the topic—that are taught by the most inspiring professors: Those professors who inspire a passion not just in the topic they teach, but also a passion for learning and for prompting students to do their best work. Search out professors who prompt students to look at the world, themselves, and possibly their career choices, differently.

A couple of years of this type of discovery will not only prepare you to select a major in which you will have a passion but also spur you to work harder and help you to develop deeper skills.

My recommendation: spend your first two years experiencing as many different fields as possible, especially courses taught by the most inspiring professors. Then, when you select a major, add courses in complementary fields.

Selecting a major will—and should—involve some soul-searching. On one hand, what you learn from your specific undergraduate major will be of little concern (and will probably have little relevance) after your first few jobs. But on the other hand, it can play three important roles in your life. It can, for example:

• Provide a powerful signal of your interests and perspective to potential employers (or graduate school admissions committees) and, depending on the major, play a big role in the type of positions for which you will be considered for your first job;

• Prepare you to pursue your passion, either as a career or as a hobby; and

• Shape the lens through which you view and interpret many of your future experiences due to perspectives and methodologies you learn, the sources and types of information you use to analyze hypotheses, and support your positions and the ways in which you express your opinions and conclusions.

Each of these is very important, but in very different ways:

• The first of these roles is the signaling, and in some cases defining (such as in planning for a career in engineering or for applying to medical school) the type of job or graduate school for which you will be considered. This will play a critical role in determining the options that will be open to you upon graduation. In some cases, however, the decision won’t so much define the types of jobs that you are likely to get as it may limit the type of jobs (or grad schools) for which you may be considered. This being said, the importance of a major in your career will probably fade rapidly after your first job (or grad school). By that time, your experiences and accomplishments are more likely to far outweigh what you studied in school in creating future career opportunities.

• The second of these roles—pursuing your passion—speaks for itself; and

• The third—providing you with the perspective with which you view and interpret the world—is likely to play a limited role in getting your first job. It may, however, play a critical role (usually much more than the knowledge you gain from your major) in determining how well you do in your first job, the options that will be open to you in the future, and even how you think about your life.

Ideally, all three will mesh, such as where your major prepares you to pursue a field that you love while also providing a strong learning environment, and simultaneously preparing you for a career in a growing field. Examples may include premed, software engineering, or teaching programs.

Creating Your Own Unique Secret Career Sauce

But what if your passion is art, archaeology, or philosophy? These can certainly be interesting and psychically rewarding passions and are often helpful lenses for viewing the world. But what employment opportunities do they offer? When the three roles of your major don’t mesh, you may have to engage in a balancing act between the near-term rewards of maximizing your job opportunities and the long-term rewards of training your mind, shaping your perspective, and pursuing your passion.

That’s where safety careers fit in. If, for example, you are intent on pursuing your passion or your intellectual curiosity, despite limited employment prospects in your chosen field, you can choose a complementary field, or at least a field around which you can craft a compelling story as to how deep skills in both areas allow you to provide a type of value that others cannot (see Chapter 6. You can do this in any number of ways, such as with dual majors (which will not only maximize your credentials, but also demonstrate your commitment and perseverance), a major and a strong minor, a major and a boot camp or MOOC program, or even two graduate degrees.

What combination? There’s no limit. They can include virtually any combination of two or more academic disciplines (such as English and political science), one discipline with a focus on a particular industry (such as economics and healthcare), or by combining computer science or business with pretty much any discipline or industry you wish. Or say, perhaps, that you have a passion for theater and are also good with numbers? How about a combination of theater arts and accounting, or a course or experience in fundraising.

Love working with computers and good in math? You’re in luck. The combination of the Internet, social media, and the growing use of embedded sensors is creating a new opportunity to capture, analyze, and identify opportunities from the vast mountains of raw data that are being accumulated on everything, from shopping patterns to the spread of infectious diseases. Indeed, combination of computer science and math disciplines is among the most sought after and highest paid combinations you can pursue. Opportunities range from earthquake prediction to bioinformatics; from Internet advertising to the pricing of Wall Street derivatives.

The opportunities for complementary combinations are limited only by your imagination, your skills, and your ability to demonstrate the value of your combination to potential employers or clients. Indeed, some combinations have proven to become so valuable and popular that they have merged into their own formal disciplines. Chemistry and biology, for example, have been combined into biochemistry and economics and psychology into behavioral economics.

Whatever you major, consider a complementary area of focus that can improve your marketability, serve as the foundation for a safety career and create a platform on which you can create your own, unique interdisciplinary “macrospecialization.”

This trend toward integrating complementary disciplines is also becoming increasingly common in graduate schools. Law schools and business schools have been offering joint degree programs for decades. Stanford Law School, for example, now offers 28 formal joint degree programs plus additional combinations students can tailor to their own interests.37 So-called science masters are one of the hottest new graduate programs.38 These hybrid degrees, which are now offered by nearly 140 schools, help students apply a business perspective to their science backgrounds and move beyond laboratories into management positions. The most popular combinations revolve around computer science, followed by information science, environmental science, natural resource sciences, math, statistics, and biotechnology. More than 90 percent of graduates in one of these combinations get jobs in their fields and more than two-thirds earn salaries above $60,000.

But whatever combination of disciplines you choose, you must do your research—and then validate your findings with potential employers. You must, for example, read about the near- and long-term career prospects in your potential field, assess current and anticipated job openings, and speak with everybody you can (including professors, career centers, and especially, practitioners) to objectively evaluate your prospects for getting a job.

It is, of course, also important to line up appropriate internships, part-time jobs, or work–study programs. Such practical experience will demonstrate your commitment to the field, help you hone your focus and skills, and allow you to see what the work actually entails and how you can provide the greatest value to potential employers.

Just as importantly, these positions (especially when paid) can also result in referrals and ideally job offers. A 2013 National Association of Colleges and Employers survey, for example, found that paid interns do more substantive work than those who are unpaid, are much more likely to get job offers (69 percent versus 37 percent—and 35 percent of those who didn’t intern at all), and earn higher average salaries ($51,930 versus $35,721—and $37,087 for those who didn’t intern).39 This being said, well paid internships are getting more and more difficult to find—especially among top employers. Goldman Sachs, for example, hired only 350 of 17,000 applicants for its summer 2013 internship program!40

Don’t be too deterred by skeptics who advise you to choose a major that is more likely to prepare you for a job. As discussed throughout this book, any major can prepare you for a job. The question is not whether you can build a career around your passion: The question is how you are going to do it!

In the end, the question is not whether you can build a career around your passion: The question is how you are going to do it!

In summary, you have almost unlimited options in selecting majors and minors. If you select and diligently pursue a field or a combination of fields based on a balance of the previously mentioned three criteria, you will be well positioned for the future—both the near and the more distant futures. The biggest mistakes you can make are selecting fields:

• On a whim or because a friend has chosen it, with no serious thought as to what it will provide you;

• That foreclose options, such as by preparing you for a narrow field with nontransferrable or leverageable skills (see for example, a Princeton Review list41 of 10 majors that will keep your options open); or worse yet,

• That are intended to produce the best grades with the least amount of work.

The majors and the minors you choose can play important roles in shaping your future. Not just in giving you an advantage in getting your first job, but in shaping your entire life. Don’t squander the opportunity—or the real value of an expensive education.

Just as importantly, while you should certainly consider the financial payoff of potential majors, don’t get blinded by the money. Selecting majors and minors solely on the basis of their practical value can be self-defeating. What value will you derive from majoring in a field in which you aren’t intellectually or emotionally engaged, and in which you won’t put in the extra effort required to develop mastery? Consider also the psychic rewards of a particular profession, not to speak of the higher level skills and the love of learning you will develop by taking courses that you find intellectually stimulating. In the end, these benefits will pay much higher career dividends than will what you learn in a particular major.

Designing Your Own Course of Study

Every job has its own specific requirements that relies on its own body of knowledge and employs its own methodologies. But, as discussed in Chapter 3, these differences are relatively small when compared with the skills that most high-demand, high-skill, high-wage jobs of the 21st Century will have in common.

The problem (which you can and must convert into an opportunity) is that these skills are changing much faster than educational organizations’ abilities to teach them. Some traditional skills (such as memorization) are becoming all but irrelevant and others are becoming little more than antes for success in tomorrow’s jobs. The real winners in tomorrow’s job market will be those who can rigorously and critically analyze complex situations and marshal required information and tools (from multiple sources and across multiple disciplines) to solve complex problems in creative and innovative ways.

Just as important as the ability to solve problems is the ability to identify problems that others may not see, to tackle ambiguous situations, and to address complex, unstructured problems that have “no right answer.” Few schools really know how to teach these skills, much less the more abstract complementary success attributes such as initiative, accountability, adaptability, and grit.

Where do you find courses for these skills in your course catalog? One way is to look for classes or activities that integrate learning and doing, particularly in project-based settings, where you take the lead in identifying the problem to be solved, the approach by which you will do so, and demonstrate the persistence and the adaptability required to achieve a challenging goal.

A second way is to find professors that inspire and require you to learn and the courses that require deep reading, which entail the researching and writing of longer papers and that give you opportunities to express and defend your ideas and to critique those of others. Many education experts believe that the best way to develop these high-level competencies is probably through self-directed, experimental project-based learning that combines book and classroom learning with experience in actually performing tasks.

The best way to develop high-level skills is probably through self-directed, experiential, project-based learning.

This approach is already well established in many apprenticeships, in some community colleges, and in medical internships and residencies. It is also common practice in German engineering schools and is becoming increasingly common in some graduate schools.42 This is especially true in MBA programs, where corporations partner with B-schools to use students as consultants on actual projects.43 Meanwhile, some law schools are beginning to structure their third-years as apprenticeships, where students work with experienced lawyers as low-fee advocates for poor and working-class clients who cannot normally afford legal representation.44

Unfortunately, most undergraduate programs have been reducing the rigor of their classes—not to speak of their grading standards (“A’s,” for example, now account for about 47 percent of all college grades). Most undergraduate schools and programs are also late to the “experiential learning party.”

You may, therefore, have to search out courses that employ “active learning,” such as interactive seminars and cooperative projects, and especially semester-long projects in which student groups work with companies, nonprofits, or government organizations to address real-world needs.45 Science, engineering, and business schools are generally taking the lead in providing such opportunities at an undergraduate level. Olin College, a small engineering school, for example, offers eight such opportunities over its four-year program.46 Northeastern University, meanwhile, is known for its interdisciplinary research programs47 and especially for its co-op programs,48 in which students in just about any discipline can get up to 18 months of related work experience in the time required to earn a bachelor’s degree.

Regardless of your chosen discipline you should drill down into your prospect colleges’ commitments and approaches to experiential (aka active or project-based) learning. Not only are you likely to learn more and gain more job-ready skills, you are also more likely to enjoy the process of learning them.

The winners in tomorrow’s job market will be those who can rigorously and critically analyze complex situations, marshal the diverse information and tools required to solve these problems in creative ways and tackle ambiguous situations for which there is “no right answer.” Since few schools know how to teach these skills, you have to take primary responsibility for learning these skills.

Another requirement for students in any discipline: take at least introductory courses that teach at least the basic fundamentals of business and entrepreneurism. First, a basic understanding of business will help in any type of organization in which you want to work, including government, hospitals, and not-for profits. Even if you aren’t directly involved in functions like accounting and marketing you will have to deal with people who are (including those who define the metrics on which you will be paid and set the budgets under which you will work). Besides, regardless of your plans, odds are that sometime in your career you will either choose or be forced to go out on your own. BE PREPARED!

A basic understanding of entrepreneurism will help not just in these situations, but also in large companies. Most organizations, for example, are devolving responsibility down to entrepreneurial business units and teams. More importantly, as discussed in Chapter 6, effective career management requires that you view yourself as a small, entrepreneurial business. You need your own brand, your own marketing pitch, and the ability to manage your own finances. Basic entrepreneurism courses, which a growing number of colleges now offer, can provide a great way of learning these techniques.

Managing the Surging Costs of a College Degree

We have all heard the horror stories:

• The steep and rapidly rising cost of tuition49 which, as of 2010/2011, ranged from an average of $8,909 for two-year colleges to $15,918 for public and $32,617 for public four-year universities and $46,899 at a private medical school—up an average of 92 percent over the last decade, compared with 27 percent for the consumer price index;

• The tuitions for once affordable public community colleges and universities are now rising even faster50 than those of private colleges;

• The crippling debt loads of college loans, in 2010/2011, which now average $29,40051 for the 70 percent of college seniors who took out loans, but can easily exceed $100,000 for those who earn professional or doctorate degrees—debts that can’t even be discharged by bankruptcy;

• The still grim employment prospects for many college (and even business and law school) graduates, with unemployment of new college grads still over 8 percent and underemployment of those who do have jobs at over 40 percent;

• The low pay that many companies that are still hiring are offering.

• And then there are the rapidly growing number of troubling critiques discussed in Chapter 7, in which employers contend that many graduates can’t even write coherent paragraphs and leading academics contend that close to half of all graduates experience no appreciable gain in critical thinking skills after four years of college.52

What’s a prospective college student to do?

While the situation can be grim, you can still get an education on the cheap. You can, as discussed in Chapter 9, take a non-college-like approach to “hacking your own education,” as by systematically creating your own experiential learning agenda, by searching out volunteer or no- or low-pay internships, and/or by building your own college program from a combination of free and low-cost online courses and certificate programs. More conventionally, you can spend two years at a public two-year college (average annual tuition of $3,131) and then transfer to an in-state public university (average tuition of $8,665).

You can further reduce these costs through combinations of grants or tax incentives. According to the College Board, about two-thirds of full-time students already receive such incentives.53 In fact, the average community college student receives enough in grants and tax breaks to cover not only average tuition expenses but also all but $10 of the average $1,230 bill for textbooks and school supplies.

But even if you don’t qualify for scholarships, grants or aid, you can slash the cost of a four-year degree. According to a Conference Board study, by the time you add in all the costs associated with going to school (room, board, and books, in addition to tuition and fees), four years of on-campus study at a private, nonprofit college can be expected to set you back the princely sum of $180,000.

There are, however, many ways of cutting these costs. One of the most cost-effective approaches for getting a four-year degree (again, excluding scholarships, grants and aid) is by combining two-years at a community college (approximately $32,000 for two years) with two at an in-state public university (a total of $46,000). Living at home (excluding additional transportation and food costs) can cut this by another $34,000, for a total of $44,000 for a bachelor’s degree. (One big caveat, however, is that living at home often comes at the expense of college socialization and networking opportunities.)54

Still a lot of money, but remember these are published rates, before accounting for scholarships and aid. While figures differ greatly by school and family income, the College Board calculates that 80 percent of all college students now receive some form of scholarship or grant. Although these packages average only about $1,500 per student, grant aid, on average, covers all tuition and fees for students from families with incomes below $30,000 (in 2011 dollars) enrolled in public two-year and public four-year institutions.55

Given the typical costs of attending college, it is of little surprise that the tough economic decade has prompted larger percentages of students to choose the public education option. In fact, over the last 10 years, enrollment in lower cost public universities increased by 28 percent and the percentage going to two-year, rather than four-year colleges, grew by 20 percent.56

This, however, doesn’t mean that a private school education is necessarily out of your reach. Although these schools certainly have much higher list prices, they often offer much larger scholarships and more aid than public schools. Some are taking more creative approaches to reducing the cost of attending. The New York Times, for example, published examples of some colleges that are freezing tuitions, promoting three-year bachelor’s degree programs, forgiving part of the tuition for students who take low-end jobs, and some that are entering into academic partnerships with local community colleges.57 Some are even offering “sales.” These include eight semesters for the price of seven (where the last semester’s tuition is forgiven for students who maintain 3.5 GPAs) and five years for the price of a four-year degree (again, for those maintaining specified GPAs).

In the end, however, some of the nation’s most elite private universities may offer some of the best college bargains of all. In fact, a highly qualified, low-income applicant can often attend a highly selective private university for less than the cost of attending a public university.

Since some of these colleges have some of the richest and most generous alumni, they have the largest endowments—allowing them to offer generous scholarship and financial aid packages. In fact, as discussed in Scholarships.com’s blog, some elite schools go so far as covering the entire cost of attending college—tuition, room, board, books, and all—for all four years for students with family income less than $60,000 per year.58 Those making between $60,000 and $120,000 will pay less than 10 percent of the total list cost of attending Harvard. Northwestern provides scholarships (averaging $15,000) to half of all its students. Duke covers all tuition—plus a summer program at Oxford and expenses—for some scholarship winners.

In fact, one of the growing number of federal government tools for assessing college costs and returns (see the following section) shows that for households with income between $48,000 and $75,000, the average net cost for a student receiving aid at one of U.S. News’ top 10 private colleges was only $9,340.59 This compares with an average net cost of $13,486 at the top 10 public universities. (And, as discussed in the following section, this does not even begin to account for the better employment prospects and higher salaries that graduates of elite universities often enjoy,

It’s a pity that more lower income students (not to speak of their high-school counselors) don’t know about such programs. A number of these schools, struggling to increase diversity in their student bases, are trying to address this knowledge gap. Some are even sending letters and emails to inform prospective lower income students of such offers in an attempt to attract many who may have not even considered these schools.

So, if you have the grades to qualify for admission to schools such as Harvard, Princeton, and Stanford, but think you lack the resources to pay for them; think again.

Comparing College ROIs

Focusing on just the costs—even net costs—of attending college doesn’t give you a full picture. It certainly doesn’t account for the fact that employers view different schools and majors very differently.

As discussed in Chapter 7, the most expensive college educations are those for which students pay tuition and take out loans, but do not graduate. They pay for the cost of this education, but receive few of the benefits of lower unemployment, better career paths, higher salaries, and more generous benefits.

According to Harvard’s Pathways to Prosperity Project, 46 percent of four-year college freshman fail to earn degrees within six years.60 Even if they do end up graduating, one-third will lose credits (and therefore money) by transferring to another college. The results are even worse for for-profit colleges. According to Education Trust’s 2008 report, The Subprime Opportunity,61 only 22 percent of these schools’ first-time, full-time bachelor’s degree students graduated within six years (compared with 55 percent at public institutions and 65 percent at private nonprofit colleges).62 Worse still, some of these schools, which also have some of the highest dropout and student loan default rates, enroll disproportionately large percentages of minority and low-income students who can least afford them.

To get a comprehensive picture of the true cost of attending a particular school you must look beyond the dollar outlays and factor in the value you are likely to derive from this degree. In other words, you must determine the return on investment, or ROI of a degree in your specific major from each college.

As discussed in Chapter 7, the average college graduate earns far more than the average nongraduate. These averages, however, disguise big differences in earnings among graduates from different schools and with different majors. PayScale’s annual College Salary Report lists the average starting and mid-career salary earned by graduates from more than a 1,000 U.S. colleges.63 It breaks these numbers down by type of school (from Ivy League to Party schools) and allows you to create your own custom comparisons, such as among liberal arts colleges within 100 miles of your home. Not surprisingly, graduates of many of the nation’s most elite universities and liberal arts colleges (Princeton, Stanford, Williams, Harvard, and so forth) and those with some of the best known STEM programs (Caltech, MIT, and NYU-Poly) earn some of the highest starting salaries.

They are, however, joined by a number of schools that few may expect: While Princeton is number one on the list, Harvey Mudd College, one of the nation’s better STEM colleges, is number two. It is joined in the top 10 by the U.S. Naval and Military Academies, a small liberal arts college (Lehigh), and an undergraduate business school (Babson) that offers a particularly strong entrepreneurship program.

When you compare the cost of attending these colleges with the salaries graduates are likely to earn, you find that a number of tier one schools (including Princeton, Harvard, Stanford, Dartmouth) and a few STEM schools (especially Harvey Mudd and Georgia Institute of Technology) yield the biggest salary bangs for your tuition bucks. If you look solely at the cost, rather than comparing it with the return, you miss the fact that some of lowest-cost colleges also yield some of the lowest returns on your education dollar.

But, as PayScale emphasizes, you can’t look at the school alone. Salaries and ROIs are also highly dependent on your major. Graduates of engineering, computer science, economics, and natural science programs, for example, tend to earn the highest returns. Those with degrees in nursing, criminal justice, sociology, and education tend to get the lowest ROIs. To drive the comparison home, the data show that a Stanford computer science graduate has lifetime earnings of $1.7 million more than a high school graduate, after subtracting the cost of education. A humanities major from Florida International University, meanwhile, earns $132,000 less than the average high school graduate. Nor is FIU alone. Twelve percent of colleges in the PayScale study produced negative returns. Thirty percent produced lower returns than you could receive by investing the money you would have paid for college in 20-year Treasury bills!

To assess the true cost of attending a particular school you must look not only at the cost, but also the salary the degree will allow you to command. Some of the most expensive school yield some of the greatest ROIs—some of the least expensive may even yield negative ROIs. Overall, community colleges offer the greatest bang for the buck.

Pulling all this information together on your own can be a Herculean task. Many colleges add to the confusion by not disclosing or by providing selective or downright misleading information. Some for-profit schools have been called out by the government for making things even worse with aggressive sales tactics and sometimes blatantly false claims.

A small but growing number of sources are beginning to provide accurate, comparative information on the gross and net costs of different colleges, their dropout and graduation rates, and the salaries that graduates can expect to earn. This will be especially true when the Department of Education launches its planned College Navigator (see the following section).64

Cutting Through the College Decision Confusion—Where to Go for Help

Choosing the school that is best for you can be extremely confusing in the best of cases. And then there are the challenges of navigating the admission process, assessing scholarship and aid options, obtaining loans and managing the resultant debt, and selecting majors, minors, and extracurricular activities. These challenges can be particularly daunting if you are the first in your family (not to speak of your neighborhood and your high school) to attend college and cannot rely on parents, siblings, or teachers for detailed guidance. But regardless of how much guidance is available to you, you should seek additional help. If your parents didn’t go to college, what about family friends or your friend’s families? Teachers and guidance counselors can also be of help, and especially those with whom you interacted (in following the steps laid out in Chapter 6 to assess your career options.

Selecting a College

You can also seek advice from third-party professionals. The most comprehensive and personalized support can come from the rapidly growing number of “college consultants” or “college counselors.” (You can find one in your area and that meets your needs by Googling these terms.)

These consultants can guide you through the entire college planning, admission, and selection process, or assist you in individual components of the process. Services can include conducting personal inventories, identifying and evaluating colleges that fit your specific personality, learning style and needs, admission test preparation, helping you through the admission process, suggesting essay topics, preparing you for college visits and interviews, identifying financial aid and scholarships, helping you make your final selection, preparing you for your first days of college, and more. Although the right consultant can provide tremendous value, they can be costly: $100 or more per hour and $3,000–$6,000 for a comprehensive engagement.65

Need help but can’t afford a private consultant? You can use some less expensive options. Unigo provides an online database that profiles and provides student reviews and rankings of thousands of colleges and universities as well as opportunities to speak with students from these schools for $29 per half hour.66 It offers subscription-based (from $199 to $599) services that include video courses of all stages of the college search, application and admission processes, and opportunities to work with Unigo consultants on individualized programs. Unigo also partners with McGraw-Hill Education to offer a college and career readiness and study curriculum that combines live events, multimedia projects, and mentoring programs.67

There are also many even less-expensive do-it-yourself options. U.S. News, for example, offers a free quiz that can help you assess your readiness for college and what types of colleges may be right for you.68 Meanwhile, a quick search, such as for “book, selecting the right college,” will point you to dozens of books that can guide you through the process. These books include the Intercollegiate Studies Institute’s “Choosing the Right College”69 and Consumer Reports’ “Find the Best Colleges for You.”70

Deciding on a Major

You can also get help in identifying a suitable and employable major. The not-for-profit College Board,71 for example, offers advice and ideas for students looking for guidance on what to study, identifying the schools which are strong in their chosen field, finding colleges that match your goals and lifestyles, and tips on choosing the right major.72 ACT’s Map of College Majors provides similar help. It allows you to see which majors tend to be best aligned with an individual’s broad interests and explains what each area of study entails, the degrees that are available and the types of occupations for which they can prepare you. (Its World-of-Work Map, meanwhile, allows you to link these findings to specific occupations, their day-to-day tasks, salaries, and so forth.)

The Bureau of Labor Statistics issues regular reports that compare opportunities for different majors and careers, as well as annual studies that compare job availability and salaries for hundreds of different occupations. Private companies, including Dice.com,73 provide detailed information on career opportunities for different majors and occupations in specific industries (technology, in the case of Dice) and others, such as PayScale, compare the salaries commanded by graduates from different colleges and in different majors.74

A number of university-based higher education research centers also provide guidance on selecting majors. These include Michigan State University’s Collegiate Employment Research Institute’s 2012 to 2013 Recruiting Trends report75 and the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce’s From College Major to Career76 website. And if you prefer to do your reading the old-fashioned way (i.e., from a book), a quick web search on “Choosing the Right College Major, Books” comes up with hundreds of titles, including the 2013 Book of Majors77 and How to Choose a College Major78, along with hundreds of websites that provide similarly focused advice. Everything College Major Test Book, meanwhile, provides a series of tests to help students select appropriate majors.79

College Costs and Returns

Getting objective, comprehensive information on and especially finding comparisons on the real costs (gross, net, drop-out rates, and ROI) of a college education is more problematic. As discussed in the previous section on Financing Your Education, sources including Scholarships.com’s blog80 and Payscale’s annual College Salary Report81 provide a good start. The Department of Education also provides a number of tools, including college cost calculator82 and basic comparisons of net college costs. The most ambitious program, and currently the best tool for assessing and comparing the true costs of different college options, comes from the Department of Education’s College Navigator.83 While this relatively new tool is being enhanced to provide better information on salaries and majors, at least one Senator (Ron Wyden of Oregon) has introduced a bill that would require the federal government to disseminate statistics on a broad range of factors, including graduation rates, salary levels, debt levels, and so forth, on the costs and returns of different courses of study at different colleges.

Whatever help you choose to get (or not to get), you can’t count on your consultant, your professors, or your college (not to speak of your friends) to craft the educational experience that will best prepare you for your dream career. You will have to take responsibility for your own education. Nor, as discussed in Chapter 10, will you be able to count on your manager, your employer, or your job counselor or recruiter to manage your career. You will also have to take responsibility for this.

Although you should seek as much advice and help as you can get, some things are just too personal and important to entrust to others.

The Graduate School Decision

Although this book focuses primarily on planning for undergraduate admission and study, I have to at least mention graduate degrees. After all, they are required for some fields and extremely helpful in others. And remember that demand for those with master’s degrees is growing faster than for any other type of degree.

But just as many college degrees are being seen by employers as “the new high school diploma,” a growing number of graduate degrees appear to be on track for becoming “the new bachelor’s degree.” This is particularly true for many liberal arts master’s degrees that recent graduates have pursued as a means of “riding out” the recession, in hopes of an improved job market. Even as the market slowly improves, many such degrees are likely to provide modest, if any, real employment or monetary value. Although they may provide some help in differentiating you from other applicants from second-, third- and lower-tier schools, there are many, many better ways of spending your postgraduate school time and money (including on many of the nondegree options discussed in Chapter 9.

Decisions on graduate school are similar to, but in some ways easier than, making decisions on college. It partially depends on the type of career you’re targeting. Is a graduate degree necessary, as in law or medicine? If so, depending on the degree, are there any advantages and/or disadvantages of pursuing the degree directly out of undergraduate school, rather than working for a few years? Many Tier-One MBA programs, for example, won’t even consider a candidate that has not had actual business experience.

In some fields, like psychology and biology, graduate degrees may not be formally required, but are de facto requirements for employment, much less for serious work in the field. In others, like business, nursing, and software engineering, bachelor degrees are sufficient (or in the case of nursing, which requires a minimum of an associate degree, more than sufficient) for most jobs. In fact, since jobs are so plentiful in some of these fields (especially nursing and engineering) and pay so well (in many IT, math, and some science fields) postponing work in favor of graduate study may incur big opportunity costs. Besides, as mentioned previously, STEM graduate degrees often return less of a salary bump over a bachelor’s degree than advanced degrees in business and many healthcare fields.

Although most professions don’t require graduate degrees for initial employment (except in healthcare, law, and tenure-track faculty positions), these degrees may be required for long-term certification (as for many teacher positions). For most other positions, graduate degrees can burnish your skills and your resume, and either qualify you for a new position or put you on a fast-track for advancement.

Occupations that typically require master’s degrees are projected to grow faster than those for any other level of education. The demand for most PhD’s on the other hand, is problematical.

Graduate degrees, however, may also have their downsides. First of all, they are costly—both in terms of out-of-pocket expenses and, if you can get a job with a bachelor’s degree, in opportunity costs. Moreover, even some of the most coveted graduate degrees—the JD and the MBA—are losing much of their luster, at least those from lower ranked schools.

Consider the employment prospects for some of the more popular and coveted graduate degrees.

Law Degrees