Transformation of the U.S. Jobs Market

. . .the underemployment rate [among recent college graduates] rose somewhat sharply after both the 2001 and 2007–09 recessions, and in each case, only partially retreated, resulting in an increase to roughly 44 percent by 2012.

—Jaison R. Abel, Richard Deitz, and Yaqin Su

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Key Points

• Higher levels of education directly correlate with higher employment rates and salaries.

• Employers increasingly require that new employees contribute immediately to the company, but are skeptical of whether many college graduates can do so.

• Underemployment is rampant, with an estimated 44 percent of recent graduates not getting jobs that require college degrees.

• Majors matter: science, technology, engineering, and mathematics; healthcare; and education graduates are much more likely to get jobs—especially jobs that require college degrees.

• Up to 95 percent of jobs lost during the recession and recovery were among the middle-income type jobs that typically go to recent college grads. Virtually all job gains are going to workers at the top and bottom of the wage scale.

• The big winners will be those with high levels of highly differentiated skills. Average performers will lose big in the New Normal.

The Great Recession marked the end of an era. A college degree, long viewed as the passport to a stable, rewarding career and comfortable lifestyle, will no longer guarantee you a job. It certainly won’t ensure a job in the field for which you have prepared—much less a predictable and secure career that allows you to pursue your passions and live a life of your own choosing.

Although reading this fact may be painful, you have to understand the future if you hope to prepare for it. You have to understand the odds, if you hope to beat them.

Employment Realities

Hundreds of studies portray and attempt to explain the current job market. Although each study has a somewhat different focus and comes up with somewhat different results (due to different assumptions, methodologies, and sampling bases), all agree that U.S. workers have taken a beating during the recent Great Recession (the economic downturn that began in June 2007). For example, although the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has surpassed prerecession levels, and corporate profits and stock markets have hit record highs, employment and wages remain far below their prerecession levels. The U.S. economy still employs fewer people than before the Great Recession. Real wages (after adjusting for inflation), meanwhile, are still below those of 1999!

All of these studies also agree on a number of other facts. For example:

• Young adults, as is often the case in recessions, have fared worse than their older counterparts. They are among the first to be laid off and the last to be hired or rehired. Compared to older and more experienced workers, they have higher unemployment rates, their time out of work is longer, their wages fall more rapidly, and they experience far worse underemployment (the ability to get a job that requires and makes use of their education). They are also less likely to get jobs that offer insurance, retirement contributions, and other benefits.

• Regardless of age, the higher one’s level of education, the more likely they are to be employed, earn higher wages, enjoy higher lifetime earnings, have longer life expectancies and lower divorce rates, and live in safer neighborhoods. Their children are also more likely to attend better schools and achieve higher levels of academic and economic success.

• Despite that U.S. educational attainment has reached record high levels (as of 2012, 33.5 percent of Americans aged 25 to 29 had at least a bachelor’s degree), employers claim they face a continual shortage of workers with the skills they need and that even most college graduates are ill-prepared for today’s jobs.

• Workers with degrees in high-demand fields, such as healthcare, education, and one of the STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), are more likely to find employment that actually requires a college degree than are those with degrees in other fields.

Behind the Headlines

Let’s look at a few findings from some of these reports and studies that illustrate the previous conclusions as well as provide a broad range of other insights important to those who hope to enter the workforce.

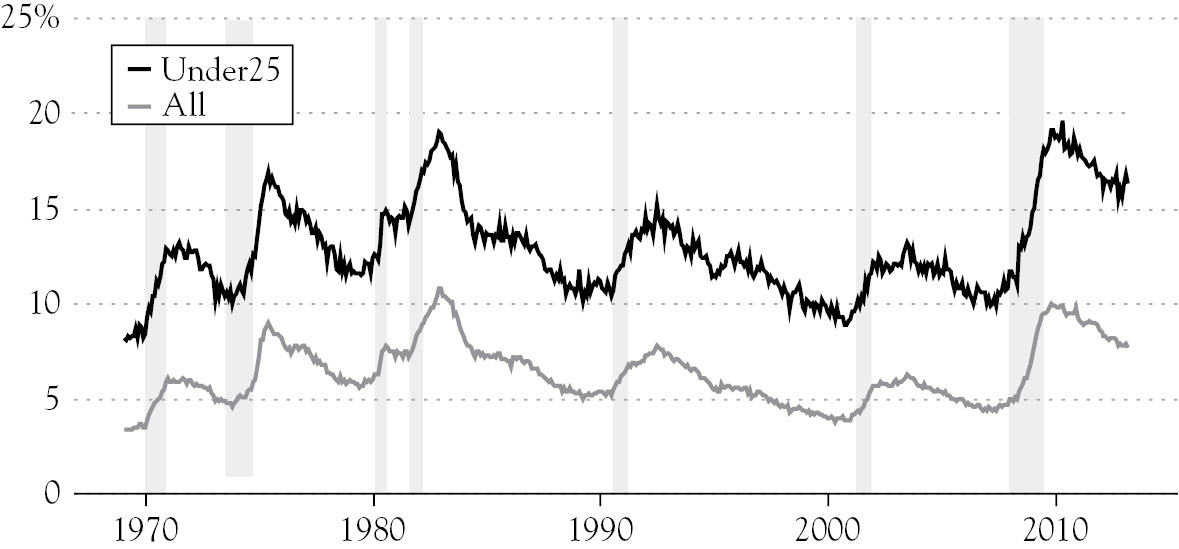

Consider, for example, unemployment rates. As shown in Figure 1.1, unemployment rates, as compiled in the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) Study “The Class of 2013,” are consistently higher for those under the age of 25 than for older workers. This gap between older and younger workers has grown greater since the Great Recession than at any time since 1970.

Figure 1.1 Unemployment rate of workers who are less than 25 years old and all workers, 1969–2013

Note: Shaded areas denote recessions.

Source: Shierholz et al. (2013), Figure A.

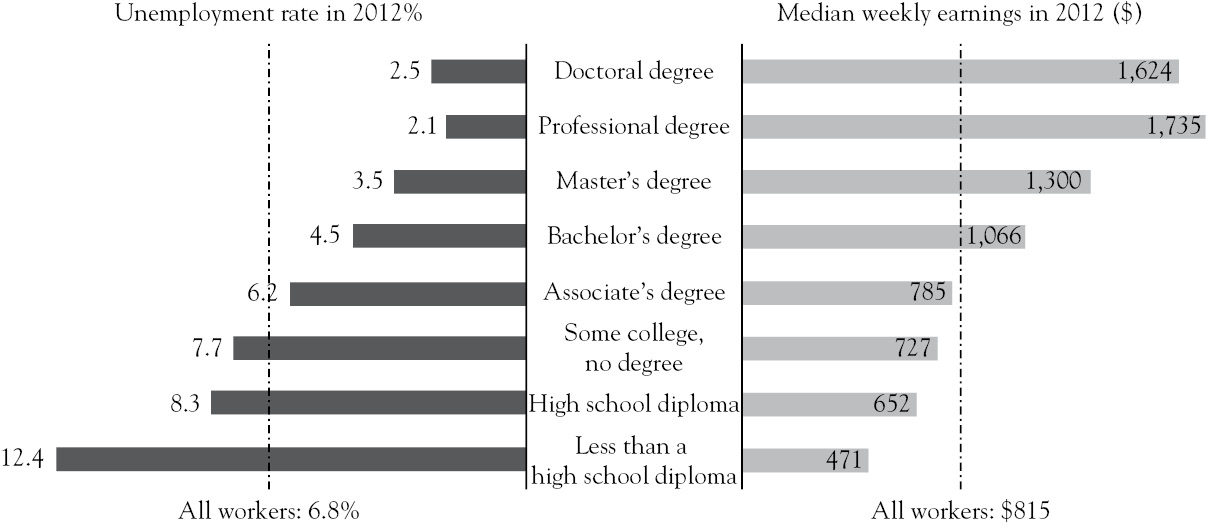

Education also plays a critical role in determining your prospects for getting a job and how much you will earn (see Chapter 7 for more details on this point). The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics2 neatly sums up the correlation between the level of education one achieves and their employment and earnings prospects (see Figure 1.2). This doesn’t mean that college grads will necessarily get jobs that match or make use of their education. However, when employers have a choice (and experience is not a deciding issue), they are more likely to hire and pay more to a candidate with a higher level of education. This education premium, which has doubled over the last 30 years, from $17,411 in 1979 to $34,969 in 2012, will continue to grow.3

Figure 1.2 Earnings and unemployment rates by educational attainment

Note: Data are for persons aged 25 and over. Earnings are for full-time wage and salary workers.1

Source: Data Table from Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey (2013)

Although unemployment rates are consistently higher for those under the age of 25 than for older workers, those with college degrees have significantly lower unemployment and higher wages than do those without.

Higher education certainly helps, but it does not guarantee a job. When comparing the linkage between education and employment across nine countries, for example, a McKinsey Center for Government study4 found that 48 percent of U.S. companies contend that a lack of candidate skills is an important reason for their inability to fill empty positions.

Accenture’s 2013 Skills and Employment Trends Survey: Perspectives on Training5 confirmed these findings. Executives at 46 percent of surveyed large U.S. companies claimed concern that they won’t have the skills their company will need in the next one to two years.6 Thirty-eight percent said they would hire more people if they could find qualified candidates.7 These skill gaps are twofold:

• Many applicants do not have the required hard skills (especially in IT, engineering, sciences, and sales).

• Even those that have these hard skills may lack soft skills such as leadership, written and oral communication, an entrepreneurial mindset, or the ability to drive change.

Recent graduates, in contrast, generally do believe their education has prepared them to get and succeed in jobs. According to Accenture’s 2013 College Graduate Survey, 84 percent of surveyed 2012 graduates thought their investment in education was worthwhile and 70 percent of those who were employed thought it prepared them for their jobs.8 To the extent they did find it difficult to find a job, 48 percent thought it was primarily due to their major.9 Only 16 percent attributed it to deficiencies in their school. (In contrast, a 2012 McKinsey study found that 44 percent of U.S. students thought their college studies improved their employment opportunities.10)

Although Accenture does see gaps in the educational system, it places a good portion of the blame on the companies themselves. So does McKinsey. In a 2013 report on talent and organization, it contends that automated resume keyword searches disqualify too many qualified candidates and that too many companies require that employees be able to step immediately into empty slots, rather than looking for candidates with a developable fit—those with good general skills and an ability to learn and respond to new opportunities.11 No matter what the cause, the result is a slowdown and a much more selective process in hiring.

The Underemployment Crisis

Whatever the reason for the mismatch, 41 percent of those survey respondents who graduated from college in 2011 and 2012 and are working indicate that they are underemployed—working in jobs that do not require college degrees.12 Forty-seven percent of respondents said their jobs did not match their fields of study.13 A number of objective studies confirm these graduates’ perceptions.

41 percent of those who graduated from college in 2011 and 2012 and are working indicate that they are underemployed—working in jobs that do not require college degree. Forty-seven percent said their jobs did not match their fields of study.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, which uses its rather narrowly defined “U-6” measure of underemployment (total unemployed, plus all persons marginally attached to the labor force, plus total employed part time for economic reasons, as a percent of the civilian labor force plus all persons marginally attached to the labor force) calculated the figure at just a shade over 13 percent at the end of 2013.14

A number of research organizations, meanwhile, specifically study the intersection of education and employment. These include:

• Northeastern University’s Center for Labor Market Studies;15

• Drexel University’s Center for Labor Markets and Policy;16

• Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce;17

• The College Employment Research Institute at Michigan State University;18 and

• Rutgers University’s John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development.19

These organizations define underemployment much more broadly, as jobs that do not require or make use of a worker’s education. Their calculations typically place underemployment in the 35 to 45 percent range.

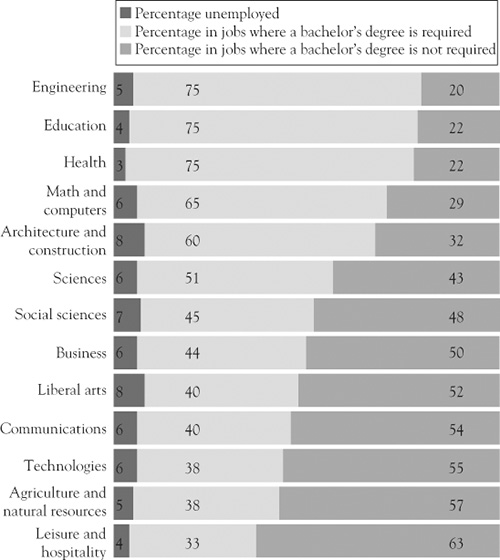

The 2014 Federal Reserve Bank of New York study, “Are Recent College Graduates Finding Good Jobs?” that defines underemployment similarly, took a particularly rigorous approach to measuring it (see the report for the description of its methodology).20 It found 44 percent of recent college graduates to be underemployed. Its calculations also showed a huge variation in underemployment by major. It, for example, found that, as shown in Figure 1.3, those who majored in high-growth, high-skill fields such as math and computers, and especially in engineering, education, and health, had very low underemployment rates. Those in lower growth fields (such as agriculture) and low-wage fields (especially travel and hospitality) were much more likely to be underemployed.

Figure 1.3 Employment outcomes for recent college graduates

Source: Abel et al. (2014), Chart 7, p. 6.

Just as those with higher educations have higher rates of employment (albeit with a much greater risk of underemployment) than those with less education, they, as would be expected, also typically enjoy higher earnings. According to the EPI’s study on The Class of 2013, young college graduates are likely to significantly out-earn those with just a high school degree: earning an average hourly wage of $16.60 per hour (the equivalent of $34,500 for a full-time worker) compared with $9.48 per hour ($19,700 for full-time).21

Wages of college graduates also fell less precipitously than those of high-school grads through the recession (7.6 percent compared with 11.7 percent between 2007 and 2012). These wage declines, however, began well before The Great Recession. By the time one adjusts for inflation, high school graduate wages have fallen by 12.7 percent since the year 2000. College grads fared marginally better, suffering a decline of only 8.5 percent.

And this does not even include big differences and recent reductions in employers’ contributions to health insurance and retirement savings. The EPI study, for example, found that in 2011 (the most recent year for which data are available), just 7.1 percent of employed recent high school graduates and 31.1 percent of employed recent college graduates received health insurance through their job (compared with 12.4 and 51.4 percent, respectively, in 2007).22 Nor does this include lower employer contributions for those who do cover insurance. Retirement fund contributions have fallen to even lower levels (5.9 percent for high school and 27.2 percent for college graduates).

Unfortunately, few of these losses are likely to be recouped anytime soon. A study of previous recessions by Yale School of Management economist Lisa Kahn found that those graduates unlucky enough to enter the job market during a recession, begin at—and continue to earn—lower wages (more than $100,000 less over the next 18 years) than people who enter the market in better times.23 A 2013 Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce study, which modeled the impact of previous recessions on earnings, estimates that those who begin their careers during or in the aftermath of the Great Recession are likely to lose a minimum of 3 percent in earnings over their lifetimes.24 Just as importantly, they also find it difficult to compete with younger, more recent graduates when normal hiring patterns resume and jobs for which they are qualified finally open up.

Then there is the debt load associated with the rapidly increasing costs of getting a college education. Roughly 40 percent of new college graduates have student loan debts that average $29,400. However, average loans often exceed $100,000 for those who go to graduate school. Such debt burdens, which cannot even be discharged by bankruptcy, are increasing, dictating career choices and confining about one in five graduates to living in their parents’ homes. And now that outstanding student debt has surpassed $1 trillion (larger than any form of consumer debt except mortgages), it is also affecting the national economy, such as limiting consumer spending and the demand for new cars and houses.25

Not surprisingly, this is all taking a toll on student and graduate morale. According to the previously mentioned 2012 Heldrich Center for Workforce Development survey fewer than half (48 percent) of recent college graduates expect to achieve greater financial success than their parents.26

Prospects for Improvement

Although the employment prospects for college graduates are still pretty dismal, they have clearly improved since 2010. And, as discussed throughout this section, college graduates have much better employment prospects than those who have only graduated from (not to speak of those who dropped out of) high school.

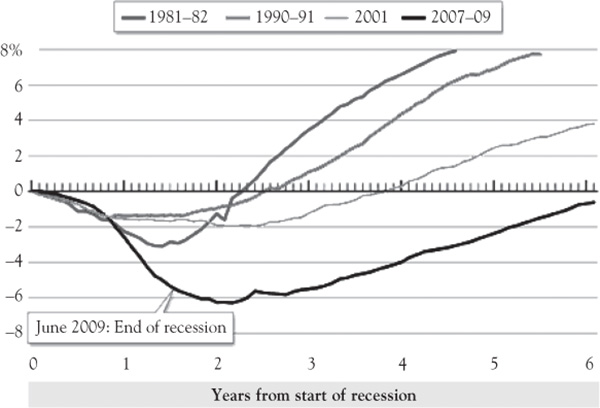

Although these conditions are likely to continue improving over the next few years, the pace of post-recession employment and wage gains have slowed dramatically since the turn of the century. After past recessions, employment and wages tended to rebound at rates similar to that of GDP. But the pattern changed after the 2000 and 2007 recessions. First, as shown in a Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis study, recovery from each of these recessions has been slower than that from each of the nine recessions between World War II and 2000.27

Second, even though GDP growth has been slow, the growth in employment has, as shown in Figure 1.4, been even slower—much slower.

Figure 1.4 Percent change in nonfarm payroll employment since the start of recession

Source: CBPP calculation from Bureau of Labor Statistics data. “Percent Change in Nonfarm Payroll Employment” (2014), third chart.

The Disappearance of Mid-Range Jobs

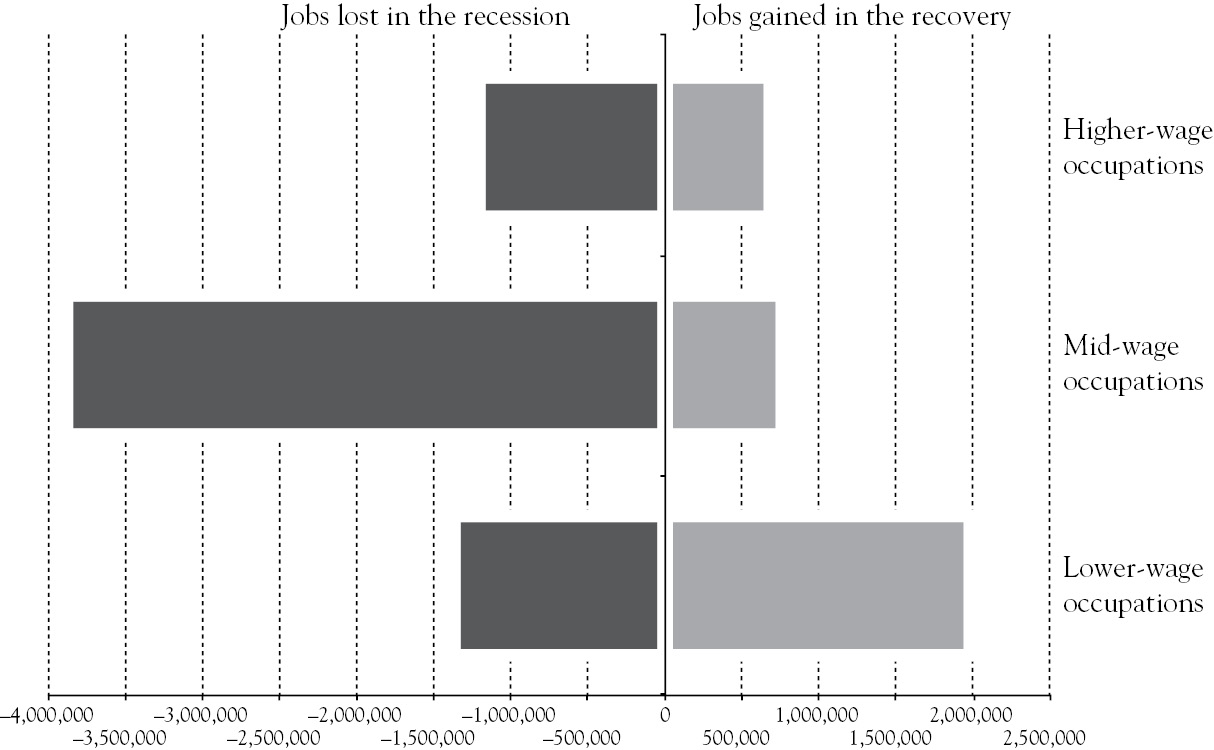

Where are the best prospects for good jobs likely to be? The National Employment Law Project study, as shown in Figure 1.5, calculated that the vast majority of jobs lost during the recession were those paying mid-level wages. The vast majority of jobs gained during the recovery have been those paying lower level wages. While high-wage jobs have also recovered a significant portion of their losses, the traditional sweet spot of the job market—especially manufacturing, construction, and mid-level office jobs—is being hollowed out.

While high-skill, high-wage, and especially low-skill, low jobs are growing, the traditional mid-skill, mid-pay sweet spot of the job market is being hollowed out.

Figure 1.5 Net change in occupational employment, during and after the great recession

Source: “The Low Wage Recovery and Growing Inequality” (2012), Figure 1, p. 2.

A Brighter Future?

It may be comforting to think—to hope—that the employment situation will return to normal once the economy reaches traditional post-recession growth rates of around 3 percent. Unfortunately this isn’t so much wishful thinking as it is self-delusion.

Although we can certainly hope for a change by the time you graduate, the U.S. Congressional Budget Office, one of the few economic research organizations that are cited and generally trusted by Republicans and Democrats alike has changed its expectations that the economy is about to see significant improvement. In February 2014, it released a report that acknowledged that a return to faster economic growth—and therefore job growth—is unlikely.28 It now anticipates a prolonged period of economic growth of about 3.1 percent per year and the average number of newly created jobs between 2013 and 2024 to fall well below the 200,000 new jobs per month that are generally thought to be required to absorb new entrants into the labor force and to significantly reduce unemployment rates.

Does this mean your hopes for a career will be dashed? Not at all. It does, however, mean that you will have to choose your career options carefully, prepare for them rigorously, pursue them systematically, and always, always have a back-up plan!

Does this mean your hopes for a career will be dashed? Not at all. It does, however, mean that you will have to choose your career options carefully, prepare for them rigorously, pursue them systematically, and always, always have a back-up plan!

Although the recession officially ended in June 2009, it took the economy until March 2014 to recover the private-sector jobs that were lost during the recession. It had not yet made up for the sharp reductions in the number of government jobs, much less created the additional jobs required to accommodate new entrants into the labor force. At that time, there were still almost two million fewer people employed than there were before the recession began. Just as importantly, as discussed later and shown in Figure 1.5, most of the jobs being created require lower skills and pay lower wages than did the jobs that were lost.

While some of the mid-skill, mid-pay jobs that were lost during the recession are certainly being recovered, most of these jobs are not coming back. They are gone forever.

One of the primary reasons for this loss of jobs is that the recession exposed a number of fundamental job market-altering trends that had been in place for more than a decade—trends that were largely masked by the financial and homebuilding bubbles. These trends, as mentioned in the Introduction, fall into four primary categories:

1. Automation, in which jobs—not just those of factory and administrative workers but increasingly of knowledge workers (as in routine accounting, programming, legal, and even some medical jobs)—are being automated. And, as argued in two recent books by two MIT professors, Race Against the Machine29 and The Second Machine Age,30 not only are these machines doing this work more cheaply than humans, they are also increasingly doing it better.

2. Globalization, which began in manufacturing, has rapidly expanded into knowledge jobs. Increasingly, educated engineers, financial analysts, doctors, lawyers, scientists, and other professionals from a growing number of developing countries perform jobs for as little as one-tenth the cost of a comparably educated domestic white-collar worker.

3. Flexible hiring, with companies looking to reduce fixed costs by increasingly looking for part-time or contract workers as alternatives to full-time employees. In addition to wanting flexibility, many are trying to save money on employee health insurance and retirement benefits.

4. Politico-economic volatility, where political, economic, social, technology, and market forces are changing so suddenly and profoundly as to make it all but impossible to anticipate, much less prepare for major dislocations or their often unanticipated consequences.

The bad news is that those who are not prepared for these trends face a lifetime of uncertainty, disrupted career plans, and low earnings. Their careers, their financial security, and, to an extent, their lifestyles will be subject to the whims of the market and the good graces of others.

The good news is that those who understand and are prepared for the job market of the future—and who plan and manage their careers effectively—have the opportunity to not only minimize these risks but also turn them into opportunities. They will increasingly be able to define their jobs around their own interests and passions, and build careers that enable, rather than limit their lifestyles.

Those who understand and are prepared for the job market of the future—and who plan and manage their careers effectively—have the opportunity to not only minimize career risks but also turn them into opportunities.

They will, for example, be able to capitalize on:

1. The growth of automation either by developing the next generation of intelligent tools or by understanding how to effectively use these tools to deliver business value in their own industries and jobs.

2. The growth of globalization by developing the type of skills required to contribute to (and increasingly to manage) global teams and to establish productive relationships with global partners and customers.

3. The trend toward flexible hiring by becoming their own bosses—giving themselves much more flexibility to tailor their careers to their lifestyles and potentially earn more money, enjoy greater job security (through client diversification), and even build companies that they can eventually sell or take public.

4. Politico-economic volatility by becoming a student of change—formally or informally helping your manager, your company, or your clients anticipate change, develop options for preparing for or responding to change, and helping them use it to their own advantage.

What does this mean for your career plan? You have three broad choices. You can focus on preparing for:

• The growing number of low-wage jobs, for which there will be many job openings, but low pay, few benefits, few opportunities for advancement, and little job security;

• The shrinking number of mid-range jobs, which will have extensive competition, require higher levels of education and skills, offer lower pay (due to increased demand and reduced supply), and offer less job security than in the past (due to continual competition from technology and offshoring); or

• The growing number of high-wage jobs, which will require high-level and increasingly well-differentiated skills, high-level cognitive and creative capabilities, strong communication and teamwork capabilities, strategic collaboration with computers, and high levels of drive and persistence.

Tough choice. Although few two-year, much less four-year college grads will want the millions of low-wage jobs that will be available, these may well be the only jobs available to those with lower level or undifferentiated skills. Mid-skill jobs will continue to be attractive, but will be limited and will face rapid erosion (see Chapter 2. Employers, therefore, will become increasingly demanding in who they hire, often mandating credentials that are not really required to do the job.

The big exception: mid-skill workers with technology skills. These skills, as discussed in Chapter 2, will be required in virtually every segment of the market. The Bureau of Labor Statistics, for example, expects technology-focused mid-skill jobs to grow by 17.5 percent through 2020—about the same rate as for high-skill jobs. And those with these skills will not only be in demand, they will also command handsome wage premiums. It is, for example, not uncommon for those with technology-based Associate degrees (and in some cases, even certificates) to outearn non-STEM Bachelor or even graduate degree holders. Then there are the high-wage jobs: the business executives, the doctors, the lawyers, the entrepreneurs, the professional athletes, and entertainers. But even ending up in one of these elite professions no longer guarantees a high salary, not to speak of job satisfaction, much less life satisfaction. Indeed, everybody will have their own criteria for determining success. It may be making a million dollars per year, it may be inventing a cure for cancer or creating an artistic masterpiece. It may be helping one other person improve their own life, or even of creating a loving, nurturing life for you and your family. Success is whatever you want it to be.

Those with the right skills will not only be in demand, they will also command handsome wage premiums.

No, you don’t have to be among the top One Percent to achieve success. Nor, at the other extreme, do you want to continually worry where your next meal or your next mortgage payment will come from. Money is certainly not everything. But as sad as it may be, money does have to be a factor in any career decision.

Bridging the Growing Wage Chasm

Although I absolutely do not want to overemphasize the role of money in a career decision, middle-class incomes and lifestyles are not what they used to be. As is discussed in detail in Chapter 2, the number of high-skill jobs—and the salaries they command—are growing. On the other hand traditional middle-skill, middle-class jobs are becoming—and will continue to become—increasingly scare. Just as importantly, the inflation-adjusted salaries that these jobs command are steadily declining. Worse still, the decline in mid-skill jobs means that those without high levels of differentiated skills will be increasingly relegated to low-skill, low-wage service jobs.

The sad fact is, that if you are not among the “winners”—the roughly 20 percent of workers with differentiated, in-demand skills—you will be a “loser” in an increasingly winner-takes-all economic sweepstakes.

It wasn’t always like this. Back in the later part of the 20th century, the gap between high-wage and mid-wage jobs wasn’t a huge problem. You didn’t have to be among the economic elite to live well. Today, as mid-level jobs continue to hollow out, the difference between a comfortable income and one in which you will have to continually scrimp is becoming a chasm.

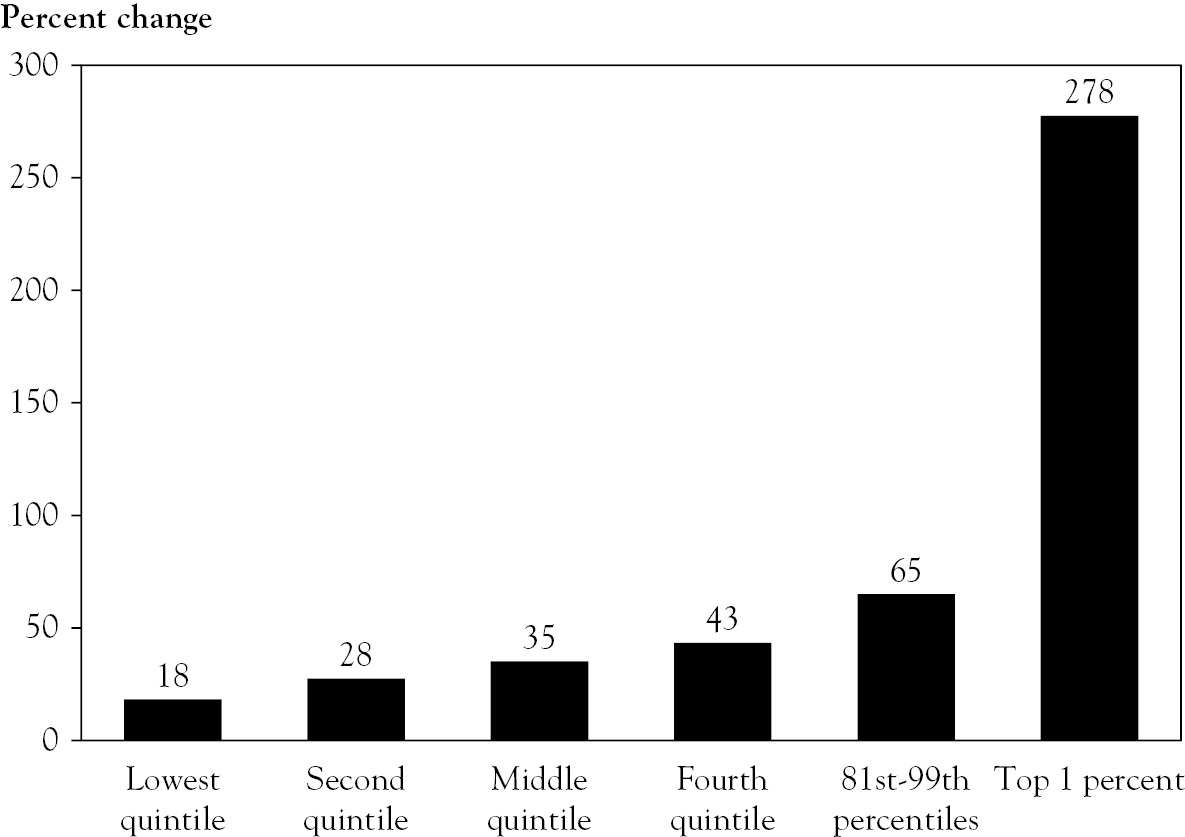

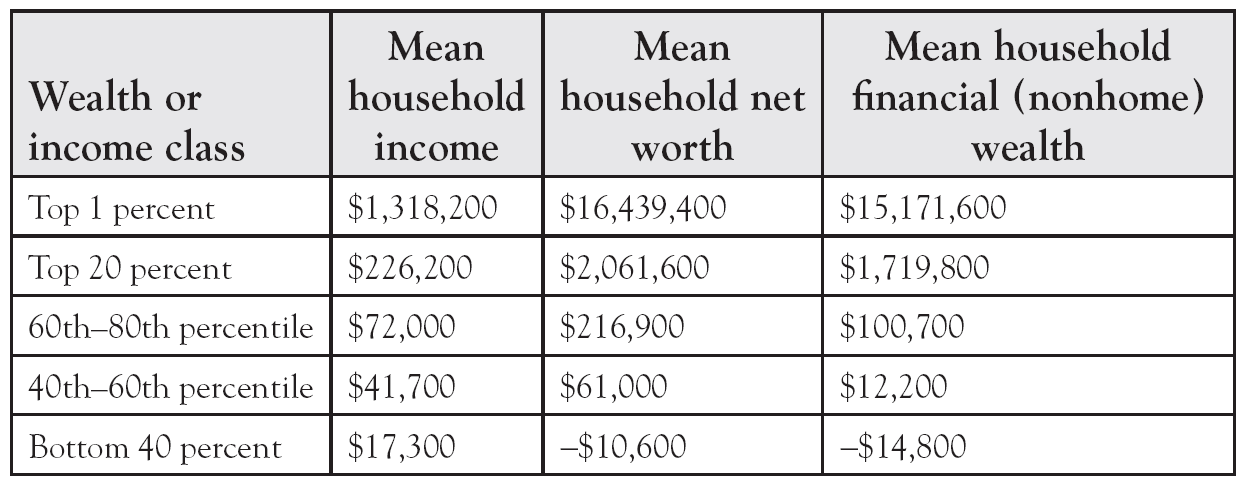

Unfortunately, although many will want one of the high-wage, high-skill jobs, few will qualify for them. Do the math. As shown in Figure 1.6, in this age of rapidly growing income disparity and superstar-driven winner-takes-all markets, the top 20 percent of U.S. households now account for more than 50 percent of the nation’s total income (earning $92,000 and above, with a mean of $226,000) and 89 percent of the nation’s net worth (a mean of more than $2 million). The division between the top 20 percent and the bottom 80 percent, however, barely hints at the widening chasm between this country’s haves and its have-nots. When you drill more deeply into this top 20 percent, you find even deeper disparities. For example:

• The top 1 percent now accounts for 19 percent of national income ($350,000 and above, with a mean of $1.3 million) and 39.8 percent of the nation’s net worth (a mean of $16.4 million)—more than the entire bottom 90 percent.

• The top 0.01 percent earn 6 percent of national income (starting at $11 million, with a mean of $31 million) and own 11.1 percent of the net worth (a mean of more than $24 million). In fact, these 16,000 households now own more assets than the bottom two-thirds of all American families!

Figure 1.6 Growth in real after-tax income, 1979–2007

Council of Economic Advisors’ 2012 Annual Report to the President

Source: “Economic Report of the President” (2012), p. 179.

These numbers fall off quickly as you move down through the quintiles. So do the rates at which the incomes of members of each quintile increase. A 2012 Congressional Budget Office study, for example, found that the real, after-tax income of the top 1 percent of American households grew by an incredible 278 percent between 1979 and 2007. The rest of the top quintile (81st through 99th percentile of households) experienced respectable gains of 65 percent. But the further the families fall down the income spectrum, the lower and lower the growth they have seen in their after-tax incomes. The second quintile (61st through 80th percentiles), for example, experienced a growth of 28 percent, while the lowest, only 18 percent.

In an era where the top 20 percent accounts for half of the nation’s total income and a staggering 89 percent of the assets, those below are increasingly struggling. They are also the ones whose jobs are less secure and whose benefits are low; those for whom a layoff or a medical emergency could cost them their homes. Consider, for example, that as shown in Table 1.1, even the second 20 percent (those between the 60th and 80th percentiles), who are doing pretty well in relation to the entire economy, had annual before-tax incomes that ranged from $61,736 to $100,065 and account for less than 20 percent of total national income. They are hardly wealthy in today’s world. This is especially the case since the majority of households in the top two quartiles are two-income families.

Table 1.1 Income, net worth, and financial worth in the United States by percentile, in 2010 dollars

From Wolff (2012); only mean figures are available, not medians.

Note that income and wealth are separate measures; so, for example, the top 1percent of the income earners are not exactly the same group of people as the top 1percent of wealth holders, although there is a considerable overlap.

Source: Domhoff (2013), Table 1.

No one, of course, should measure his or her success or life’s worth by money. Everybody, however, wants to have income sufficient to buy a comfortable house, feed his or her family, afford the occasional vacations and luxuries, and afford to fund increasingly expensive educations and ever-longer retirements. Although few people (at least outside expensive cities such as New York, San Francisco, Boston, and Washington) need $226,000 in annual income (before taxes) to live comfortably, these percentiles are at least convenient surrogates for thinking about the winners, the stars, and the superstars in the national jobs sweepstakes.

As discussed in The Second Machine Age, this disparity is likely to grow even greater as three overlapping classes of economic winners further separate from the rest of the pack:31

1. Those who accumulate the right capital assets, either nonhuman capital (such as land, equipment, and money) or human capital (such as training, education, experience, and skills) versus those who do not;

2. Those who do nonroutine work (cognitive, creative, athletic, etc.) versus those who do routine work (routine and rules-based jobs such as manufacturing, bookkeeping, administrative, etc.); and

3. Superstars who have special talents and/or a lot of luck versus those with less and less differentiated talent and less luck.

You don’t have to be a superstar to build a financially, not to speak of a psychically, rewarding career. In tomorrow’s market, however, you will increasingly have to be a star—a high-value, well-differentiated provider of some type of service or product that others will value. As professor Tyler Cowen32 and journalist Thomas Friedman33 have been telling us, “Average is Over.” Those with only average skills, average personal brands, and average determination will have no place in the world of the career stars, much less the superstars. Average workers—regardless of their education—will be increasingly relegated to average jobs, those that barely pay living wages and for which advancement opportunities are limited.

You don’t have to be a superstar to build a financially, not to speak of a psychically, rewarding career. In tomorrow’s market, however, you will increasingly have to be a high-value, well-differentiated provider of some type of service or product that others will value.

After all, now that 38.7 percent of young adults are now graduating from some form of college, only about half of them can even realistically aspire to the top 20 percent, much less the top 1 percent. The good news is that the younger you are, the better your chances of putting yourself in a position to achieve your economic, as well as your career goals. But whatever your age, you need a plan—a plan to develop your own unique value proposition and to create a differentiated, high-value brand around yourself and your value proposition.

No, this book won’t provide a detailed game plan to help you reach the top 1 percent or any other specific income strata. However, it will help you decide upon, prepare for, and find (or increasingly invent) a good job in whatever you select as your first career: Ideally a career that will build upon your interests and skills, feed your passions, and enable the lifestyle you choose for yourself. To the extent that money is part of this plan, it will suggest opportunities for shaping your career in a way that will improve your odds of getting a reasonably well paying job.

Notice also that the previous paragraph refers to your first career. Odds are extremely high that you will have two, three, or more different careers during your work life. This book, therefore, examines not only the skills, the personal attributes, and the resources you will need to find your first job, but also those that will equip you with the flexibility of changing your career, if you choose or need to do so.

But before getting into the steps you should take to prepare for the jobs of the future, it is important to understand exactly what the jobs of the future will (and will not) look like and the skills you will need not only to get these jobs but also to succeed in them.