7

The New Basics

Inner Work for Adaptive Challenges

Katherine Tyler Scott’s essay describes why it is that leaders need to do their inner work to be able to meet the challenges they face today. Many of the participants in the Fetzer dialogues credited an internal call in the face of a compelling need in the world as their motivation to lead. Many also described a feeling of certainty that a particular setting or issue was theirs to take on. This awareness drove them to develop inner qualities that incrementally allowed them to meet the next challenge (and the next and the next) that arose on their leadership journeys. The forms of such spurs to growth are many, but Scott focuses primarily on the necessity of facing one’s fears and repressed qualities to be able to surface conflict and manage change.

A well-developed self in a leader—what I call self-differentiation—is not only critical to effective leadership; it is precisely the leadership characteristic that is most likely to promote the kind of community that preserves the self of its members.

—Edwin Friedman

In the work of transformation, who the leader is, is as important as what the leader does. If we desire to be leaders of transformation, we must focus much more on developing the discipline of inner work connecting our cognitive functions with the unconscious and introducing individuals and organizations to a much larger and richer internal world. While leaders and leadership educators need not have clinical social work, psychology, or psychiatry degrees, a competent understanding of adult psychological development within a larger sociological context is an advantage.

Inner Work

When we engage leaders in an exploration of the deeper parts of the self, we are laying a foundation that enables them to bridge the outer and inner aspects of life, and we are helping them to see themselves and others in ways that make more of themselves and more of others. The inner work of leadership leads to increased consciousness and healthy ego development.

Jung likened the ego to “a cork bobbing along in an ocean”—the ocean being the unconscious. This image conveys the enormity of the unconscious in comparison to the ego, but what the ego lacks in size it makes up for in consciousness. While the conscious and unconscious are indistinguishable in the beginning of our lives, the journey of individuation and ego development is simultaneous. The ego serves as the mediating force between our conscious and unconscious selves.

The task of becoming a person, of becoming self-differentiated, involves the ego’s ability to go to the center of the unconscious and work with both the divine and the demonized aspects of one’s self. The work of reclaiming these aspects of the self, which have been denied and repressed, and finding ways to constructively engage and integrate them into our conscious lives is the inner work needed for transformational leadership.

As Robert Johnson (1986) writes in Inner Work,

The purpose of learning to work with the unconscious is not just to resolve our conflicts or deal with our neuroses. We find there a deep source of renewal, growth, strength, and wisdom. We connect with the source of our evolving character; we cooperate with the process whereby we bring the total self together; we learn to tap that rich lode of energy and intelligence that waits within (p. 9).

As one executive described the journey:

The process of inner work helps me to consider how I handle myself during the big setbacks, because that is what defines a leader. I find that I have to be straight and honest with myself because unless I am straight with myself, I can’t be straight with others. This is the deep trust factor that emerged from the inner work. It all starts with the internal awareness, and then moves to the external awareness. When your values are aligned, and you deliver on what you say you are going to do, people begin to trust you…. This work eventually links you to your sense of spirituality; it deepens your perspective on what you’re really all about—what makes you tick. That deep sense of inner awareness is what helps me in becoming a more effective leader every day. [participant in The Inner Work of Leader workshop, (2009)].

Leaders who don’t engage in inner work are more prone to incongruent behavior and disconnects between what they believe and what they do, between what they intend and what actually happens. We have observed this dynamic in public leaders involved in scandalous situations that destroy their careers and reputations. Accounts generally describe their behavior as “uncharacteristic” or “out of character,” implying they were not themselves. But what emerged is what had been previously disowned and denied.

In the field of health care, the disconnect between intent and impact is termed iatrogenic—the intention is to heal but the impact is to do harm. Leaders are likely to be iatrogenic when they act from a place of unawareness and unconsciousness. An example follows.

George was the gregarious, outgoing, well-liked CEO of a large institution, who hated conflict and would do almost anything to avoid it. He frequently used his great wit to quell any sign of discontent or emerging disagreement. George was so competent at repressing his own anger, he could convincingly say, “I never get angry.” He consciously believed this, but his inability to recognize and claim his own anger made it difficult for anyone else in the organization to express it openly, so his shadow became theirs as well, and his behavior became a cultural norm.

The avoidance and repression of anger made his executive team unable to consciously develop the skills needed to resolve intragroup conflicts. Although he could see that this was a problem, George could not make the connection between his behavior and the culture that had been created. Engaging in inner work would have enabled him to gain insight into the relationship between his avoidance of conflict and the team’s inability to address or solve problems in which there was a conflict or the possibility of it. When George left the company to take another position, what lay unresolved and smoldering between staff erupted. Without having had the experience of openly working through conflict, the organization went through a period of crippling chaos, confusion, and incivility.

The ego’s engagement of the shadow is essential to transformation, for it is a vital part of the psyche. Denial of its existence only serves to strengthen its power and the possibility of destructive and damaging behavior. John Sanford (1994), Jungian analyst and Episcopal priest writes about the perils of ignoring or repressing the shadow; “the shadow is never more dangerous than when the conscious personality has lost touch with it.” (p. 55). He continues; “We are more likely to be overcome by the Shadow when we do not recognize it.” (p. 64).

Leaders of transformation understand that just as individuals have both public and private realms of their being, organizations have visible and invisible aspects of their culture. Experiences over time have shaped their responses to certain circumstances and created a pattern of what is acceptable and unacceptable, what will ensure sustainability and what is threatening to the organization’s survival. What the organization learns becomes internalized in the culture—norms, values, expectations, beliefs, behaviors, and assumptions—some of which are unconscious and unquestioned. The behaviors and decisions of an organization and its leaders and followers are influenced by all of these factors.

As with individuals, organizations seek approval and want to publicly project an ideal image. Those aspects of their culture that don’t fit this image are repressed and become part of the organization’s shadow. Some behavioral indications of the existence of shadow in organizations are overly polite behavior in meetings in which nothing of substance gets identified or discussed, overreaction to an issue, extreme defensiveness, information overload with no time to really deal with it, meetings in which no one in the group speaks up or shares an opinion that differs from anyone else, and so on. Many organizations spend millions of dollars annually helping their employees learn to deal with the symptoms of shadow rather than dealing directly and constructively with the source of the symptoms.

Leaders of transformation understand that the suppression of shadow is time and energy consuming and reduces the creativity and productivity in an organization. Making the shadow within an organization conscious and integrating it quickens the pace of change and transformation.

Leading Change from the Inside Out

An organization can be transformed when the leadership has the capacity to claim both the visible and invisible aspects of its culture. Understanding how change occurs and its impact on individuals and organizations is central to the work of transformation.

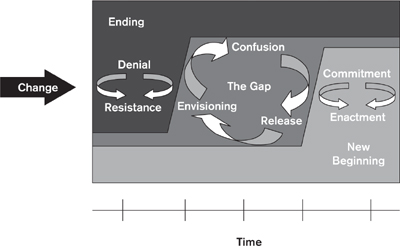

When individuals and organizations encounter change, there are predictable emotional states and responses. The traditional norms and behaviors that have served as defenses in keeping the shadow at bay are challenged, which means that feelings and behaviors that usually are invisible become visible. The Three-Stage Model of Change is an integration of the research on change, systems theory, and grief work, and describes what happens in this process.

When change is introduced, individuals and organizations experience an ending, the gap, and a new beginning (Figure 7.1).

In the Ending, or the first phase of change, about 75 percent of people are in denial and resistance. Many feel highly anxious and fearful, and may act to keep the status quo in place. About 10 percent acknowledge the change but aren’t clear about what it means or how they will adapt. The remaining 15 percent embrace the change and move to implement it.

In the second phase, the Gap, about half of those affected by the change have transitioned into a phase of mixed anxiety, confusion, bewilderment, grief, a beginning of letting go, and embracing the new beginning. Individuals and organizations experience considerable stress during this time. Attempts to alleviate the anxiety and confusion can be regressive unless there is frequent, consistent, and clear communication by the leader of the change about process and progress. Those who have already embraced the change remain constant in their commitment, but even under the best of circumstances about 25 percent of those in the change process remain in a stage of denial and resistance.

Figure 7.1 Ki ThoughtBridge’s Three-Stage Model of Change (copyrighted); influenced by Hero of a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Revised in 1972. Adapted from William Bridge’s and John Kotter’s work. William Bridge’s presentation to the TLD Leadership Education Forum, April 16, 1999, Indianapolis, IN.

During this time, ways of speaking and acting that may have been taboo in the past may now be encouraged. Yet, emotionally, people still have fear about speaking the unspeakable or trying what was perceived as undoable. For example, in the previously described organization, even after George left, some remained fearful of expressing anger, and others felt like they expressed it so destructively that it was dangerous to acknowledge it. The lack of skill and low confidence contributed to the persistent reticence to discover the shadow within.

The leader of transformation has the task of easing people into the work on the shadow so that they can be freed from their fears and liberated to claim the gifts the shadow has in store as well. When equipped with the right tools and skills, people can learn how to deal with conflict with grace and ease.

In the New Beginning, the third and last phase, 75 percent of the people are on board. The release and envisioning that began toward the end of the Gap continue, gaining momentum and shifting the energy and focus toward creative visioning and implementation. Those involved begin to openly invent ways to bring about the change. It is now clear that people who are dispensing with old rules and trying new ways are being rewarded, not punished. The emotionality in the organization changes from anger, fear, anxiety, and ambiguity to anticipation, openness to learning, excitement, and a sense of efficacy in accomplishing the change. There is still a small percentage of those who have not moved from denial and resistance and who are still caught in the Gap. Whether they can move from being stuck or not is a key question that leaders of transformation need to answer when deciding how to invest and maximize resources and on whom to focus attention and support.

Managing the intensity of emotions and the vast range of behaviors found in each of the three phases of change requires conscious, self-differentiated leadership. If leaders lack the ability to recognize and manage their own emotions, it is unlikely they will be able to manage others’ emotional responses to change. Those who have done such work have the advantage of being able to empathize with what others are going through and can normalize feelings by talking about them and how and when they are appropriate. In addition, they can express how a part of them also misses how things used to be, making it acceptable for some not to be fully on board with the new changes. If what has been in shadow is now out in the open, the wise leader also understands that its expression at first may not be pretty—but in time the new behaviors will become integrated into people’s ways of being and acting with one another.

The Arthritis Foundation provides a positive example of what can happen when emotionally intelligent leaders who have grappled consciously with change in their own lives lead organizational change. Originally structured as a federation with a national headquarters and a network of fifty local affiliates, separate corporate entities, bound together through a charter process, the foundation recognized that it needed to be structured in ways similar to other respected not-for-profit organizations.

Maintaining a strong local presence and the capacity to raise funds and deliver programs was critical to success, and bringing staff and volunteers along in the process was very important. So the board convened a design team of approximately 100 respected leaders, representing every chapter across the country, to help define and design the new governance structure. These leaders became the “change team” with whom we worked to lead this large-scale change.

As with any major change initiative, there were multiple, often critical, negotiations to reach a new consensus regarding structure. The Arthritis Foundation’s leadership did not panic when conflict emerged because they had the tools to manage it and achieve constructive outcomes. Arthritis Foundation chief operating officer Roberta Byrum’s investment in her own inner work enabled her to see that the design team and her staff needed a different set of skills and tools to navigate the transition. She reached out to equip her team with (1) an understanding of the process of organizational change and transition, and (2) a set of adaptive skills, tools, and processes to equip them to get through the Gap, a stage best described as “a time of no longer and a time of not yet” (a phrase inspired by Hannah Arendt [2006]).

Roberta Byrum says, “This work has had a lasting impact on our organization. As we moved forward with the restructuring, those who served on Design Teams had integrated the tools and processes introduced to them.” (2010).

Leaders, such as those of the Arthritis Foundation, who are in touch with their own phases of change and are aware of the impact of such changes on their own psyches and those of others in the organization can implement transformational structural change in ways that also build the change management capacities of the organization. In the process, they develop the organizational abilities needed to thrive in today’s fast-changing world.

Wise leaders know that the process of transformation takes time, but that people and organizations can and will change. The ability to know and understand change and transformation, to persist and persevere with empathy and strength through difficult and challenging phases, is the mark of leaders who have done their own deep inner work in which the whole self has been engaged, and in doing so can become catalysts for transformational change.

Katherine Tyler Scott is the managing principal of Ki ThoughtBridge, a company specializing in an integrated model of leadership development, the management of change, resolution of conflict, and negotiation training. She is the founder and former president of Trustee Leadership Development, Inc. Katherine is a nationally recognized speaker and consultant and the author of Creating Caring and Capable Boards: Reclaiming the Passion for Active Trusteeship (Jossey-Bass, 2000); The Inner Work of the Leader: Discovering the Leader Within (1999); and Transforming Leadership (Church, 2010); and contributing author to Spirit at Work (Jossey-Bass, 1994). She serves on the board of the International Leadership Association and is a contributor to the Washington Post’s On Leadership blog.