2

Foundations and Definitions of Theory Building

THE PURPOSE OF THIS CHAPTER is to establish the foundations and definitions of theory building in applied disciplines. Specifically, this chapter will

• present definitions of theory,

• describe the differences between theories and models,

• summarize philosophical orientations in theory building,

• discuss research paradigm approaches to theory building

• distinguish between types of theories,

• identify existing foundation work on theory building,

• discuss theory frameworks, and

• present general criteria for judging the quality of theories.

The information in this chapter is necessary and relevant for theory development research. While each of the chapter’s major sections could comprise a book, our goal is to abbreviate. Rather than engaging in lengthy debates on each of these topics, we attempt to clarify perspectives as they relate to the theory-building method presented in this book.

DEFINITIONS OF THEORY

Any attempt at describing how theories are developed requires clarity about exactly what constitutes a theory. It is easy to see that the term theory is not universally interpreted. For example, we often hear that everybody has a “theory,” which really means nothing more than an armchair opinion. This kind of theory can simply be taken to mean an idea or hypothesis—perhaps based on some personal experience. Ideas or hypotheses that have not been evaluated with rigor, that do not have evidence to support them, or that lack verification from any alternative source do not qualify as theory in the learned world. Theory in a more serious sense is built of ideas that have been translated into measurement criteria, examined in detail, and tested by using an established, rigorous method.

Clearly, there are many definitions of theory. We refer to the following definitions in discussing theory building in applied disciplines:

• A theory describes a specific realm of knowledge and explains how it works.

• Applied disciplines are realms of study and practice that are fully understood through their use in the functioning world.

Some additional theory definitions that have appeared in the literature are as follows:

• “A system of assumptions, principles, and rules of procedure devised to analyze, predict, or otherwise explain the nature or behavior.”

—American Heritage College Dictionary (1993, p. 1406)

• “A theory tries to make sense out of the observable world by ordering the relationships among elements that constitute the theorist’s focus of attention in the real world.”

—Dubin (1978, p. 26)

• “Theory is a coherent description, explanation, and representation of observed or experienced phenomena.”

—Gioia and Pitre (1990, p. 585)

• “Theory building is the process or recurring cycle by which coherent descriptions, explanations, and representations of observed or experienced phenomena are generated, verified, and refined.”

—Lynham (2000a, p. 8)

Theories Versus Models

With advancements in multivariate testing, scholars increasingly examine a variety of independent variables and their effects on a wide range of outcomes (Thompson, 2004). Complex mathematical analysis tools (e.g., structural equation modeling, path analysis, hierarchical linear modeling) make it easy to test several ideas without the difficult logical framework development required for true theory building (Dubin, 1978; Thompson, 2000). Research studies using mathematical analysis tools can make important contributions to theory development, but the tools themselves do not create theories. Scholars advancing a specific method rarely go beyond modeling sets of variables so that advanced statistical techniques can be applied. In other words, research driven by techniques, rather than questions, seems to be a disappointing trend in the social sciences that results in models, not theories. These practices demonstrate the need for a distinction between models and theories.

Theories and models are two different things. Theories almost always incorporate models, but models do not necessarily require theories or a theoretical foundation. The majority of scholars position models as a smaller component of theories (Carnap, 1938, 1971; Coombs, Dawes, & Tversky, 1970; Kaplan, 1964). Throughout this book, the terms theory and model are not used interchangeably. Applied theories are taken as larger, complete representations of system activities. Models are therefore smaller optional subsets of theories.

PHILOSOPHICAL ORIENTATIONS FOR THEORY BUILDING

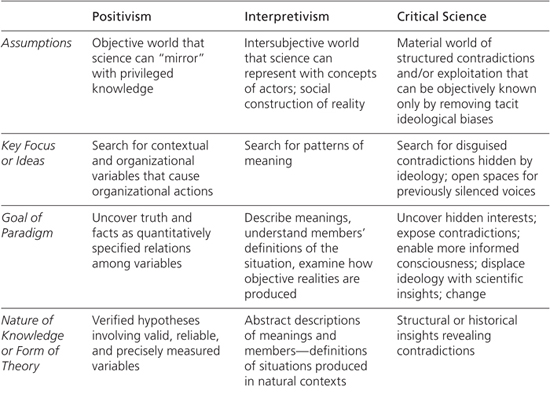

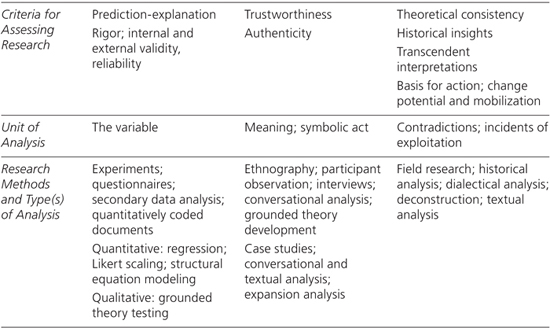

A theory builder’s philosophical orientation is not the defining feature of theory development (Swanson, 1988, 2000). Some politicized scholars choose to dwell on engaging in philosophical debates versus describing the actual building of theory. While philosophical orientations certainly influence theory-building efforts, the purpose of this book is to detail a five-phase General Method of Theory Building for Applied Disciplines. However, varying philosophical orientations may be particularly useful for specific phases of theory building and specific realms being theorized. Consistent with our purpose of abbreviation, a summary of philosophical orientations is useful. Common philosophical orientations in theory building are positivism, interpretivism, and critical science (summarized in Figure 2.1).

Positivism

The positivist philosophical orientation to theory building is based on the scientific method and traditional hypothesis testing. Reality is objective, and the theorist’s task is to establish laws that can predict outcomes in an area of human/human systems activity. Typically, positivist work in applied disciplines has wide application areas and attempts to mirror the goal of the natural sciences—to establish universal laws. The positivist orientation includes hypothesis testing, of course, but it can also include case studies, grounded theory (Glaser, 1992; Glaser & Strauss, 1967), and other methods depending on the purpose of the theorizing, the defined boundary of the resulting theory, and data-gathering and analysis techniques. Examples of positivism feature attempts to model the social sciences on the physical sciences and establish laws similar to those in the physical sciences. Human capital theory is an example of positivist theory development in the sense that it generally establishes a “law” that as education levels increase, so does productivity (Becker, 1993).

Interpretivism

Critics of quantitative work suggest that human/human system behavior is far too complex for universal laws. Proponents of an interpretive orientation argue that attempts to mimic the natural sciences result in a loss of meaning. The loss of meaning prevents interpretation, which is a rich data source that aids in a deep understanding and description of why some human activity may occur (Van Manen, 1990).

FIGURE 2.1 Alternative Paradigms for Research in Organizations

The interpretive orientation includes some specific techniques such as phenomenology, but it can also include case studies and grounded theory efforts—again, depending on the purpose of the theorizing, the defined boundary of the resulting theory, and data-gathering and analysis techniques. An example of an interpretive study would be anomalies in medical research. When a patient does not respond to a specific treatment in the same manner that the majority of other patients do, researchers might ask why and learn that there are contextual differences (perhaps environment) that negate the effects of treatments that benefited other patients.

Critical Science

Critical science seeks to “surface unacknowledged forms of exploitation and domination” (Swanson & Holton, 2005, p. 21). Critical scientists study oppressive conditions, usually related to social structures. They often view their purpose as one of social change by exposing policies and processes that keep hierarchies in place and prevent the ability of each human being to realize his or her full potential.

The classic example of research framed from a critical science perspective is the work of Paulo Freire. His efforts in Brazil working with a largely illiterate population provided a perspective to consider the politics of education. He eventually came to the opinion that nothing is free of political agendas and that freeing marginalized groups was an important cause. More modern examples of research drawing on a critical perspective might examine women leaders in corporations or the experiences of African American managers.

RESEARCH PARADIGMS IN THEORY BUILDING

In addition to philosophical orientations, theorists must deal with research paradigms, which typically connect to methods. The common paradigms in applied disciplines are quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. Research paradigms are important because their use allows some degree of flexibility in an overall research agenda. Most theory-building efforts involve multiple research studies, and theorists can alter the paradigm for individual studies.

It is easy to see how paradigms can be applied independently or in combination. For example, a multiple-regression study of the factors that influence employee motivation would be using a quantitative paradigm. A set of semistructured interview questions with employees asking about their motivation would be using a qualitative paradigm. And both studies could be conducted from a positivist philosophical orientation. On the other hand, a pure phenomenological study could be conducted that would certainly stem from an interpretive orientation and be classified as a qualitative paradigm.

Research paradigms are the framework used in each of the theory-building phase chapters of this book (Chapters 4–8) because they are apolitical and function at the methods level. Featuring the methods level is critical in meeting a core goal of this book: to provide some guidance for how to engage in theory building. From a foundational point of view, it is useful to provide general descriptions of these research paradigms before digging in deeper.

Quantitative. A quantitative paradigm uses data in quantitative form to answer research questions. Often this approach entails testing and measurement, surveys and number-crunching software programs to analyze data, along with statistics to describe the results.

Qualitative. A qualitative paradigm refers to the use of descriptions. As its name implies, the focus of inquiry is on the qualities related to some domain of human/human systems and strategies for describing those qualities are used.

Mixed Methods. A mixed methods paradigm in theory building uses multiple strategies for collecting and analyzing data that involve both quantitative and qualitative paradigms. This approach allows a great deal of freedom.

Research Paradigms

There is no process that will allow the theorist access to clear answers and direction for reconciling conflicting assumptions and ideas. Instead of requiring complete resolution to philosophical issues, theorists would do well to recognize the inherently messy nature of theory building and avoid paralysis by moving on. The research paradigms we have described are examined in more detail in subsequent chapters where the goal is to demonstrate the differences in paradigms as used in theory building in applied disciplines.

We recommend three key criteria for moving past lengthy philosophical debates that don’t advance applied theory building: (1) emphasizing the purpose of the theory-building effort, (2) paying close attention to the intended boundary of the theory, and (3) promoting cohesion among the choices throughout the theory-building effort. Boundaries are discussed at length in Chapter 4, but for now it will suffice to say that boundaries establish the context and location for the expected operation of the theory. The purpose and the boundary will enable the theorist to move forward. The concept of cohesion refers to all of the elements wrapped up in the theory and applies to the purpose, content, measurement strategies, assessment strategies, and use of the theory. Alignment among these aspects of theory building is what we refer to as cohesion, and we revisit the concept throughout the remaining chapters.

TYPES OF THEORIES

Grand, midrange, and local theories are three different types of theories. Because theory builders in applied disciplines deal with a variety of different contexts, the specificity of their theories must vary as well. Think of a camera lens and the zoom function. The wide-angle view gives the most comprehensive picture, but the details are fuzzy. Extreme close-ups can also be taken, but the “scene” is blurred or missing. Then, there is everything in between. Let’s examine these three types of theories more closely.

Grand Theories

Grand theories usually have the widest boundaries in applied disciplines and can be likened to the wide-angle camera lens. They are usually aligned with the quantitative philosophical orientation and aim to establish generalizability of the findings.

Grand theories in applied disciplines most closely emulate theories in the natural sciences because they are attempts at establishing laws, or general principles that apply universally (or as close as possible) to human activities. The theory of human capital—and the premise that over our history, education is associated with increased income and a better quality of life—is an example of a grand theory (Becker, 1993). While this is perhaps not true in every single instance of education, data show the trend over time. Theories of human behavior like stimulus-response and McGregor’s X-Y theory (1960) are additional examples of grand theories because they attempt to explain general human/human systems behavior regardless of location, class, education, or other variables.

Midrange Theories

Midrange theories are more specific than grand theories, and they tend to be categorical, explaining relationships that exist and predicting outcomes within a bounded domain. Midrange theories apply to situations that do not attempt to establish universal laws but go beyond describing single instances of human activity. In other words, there is some degree of generalizability or transferability of what is learned from the theory building. For example, research on the financial performance of Fortune 500 companies, research on training and development in the automotive industry, and research on the experiences of women in leadership positions might contribute to midrange theories. Theories commonly used in nursing also exemplify midrange theories because they are expected to explain and predict outcomes generally, but within the context of patient care or other nursing-related situations. Documented studies of innovation and knowledge management at Xerox (Earl, 2001; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995) are also good examples of potential midrange theories because they illustrate how studies of innovation and knowledge management were conducted in one corporation and then distilled into practices that other corporations might consider adopting.

Local Theories

Local theories are very specific and so tightly coupled to a context that the context itself becomes part of the theory. They are theories that are intended to apply in a small number of instances, sometimes only a single instance of human/human systems activity. Local theories are often based in the social construction philosophical orientation, and they are not required to be generalizable to any other instance. To use a term from the quantitative philosophical orientation, local theories are often outlier instances of human activity. For example, when outcomes deviate from grand or midrange theories (the outliers), local theories often result from attempts to understand the unexpected results. An example of a local theory would be an in-depth study of innovation practices at Apple, Inc., since other companies cannot really compete. The idea that frames local theorizing is that something unique is going on that is difficult or impossible to replicate. Research efforts attempt to describe the uniqueness in ways that generate insight, but they are not intended to be used in alternative situations or contexts.

Theory Type Connections

The importance of the connection between theory types and the theory boundaries cannot be overstated. Grand theories have wide boundaries and are expected to be generalizable. Local theories are by definition much smaller, apply in selected or specific areas of human activity, and may be minimally transferrable. In between these two are midrange theories, which have the greatest degree of flexibility. With that flexibility comes the responsibility for clarifying decisions in the theory-building process and providing a logical connection among a theory’s varying elements (which are covered throughout the rest of this book).

EXISTING WORK ON THEORY BUILDING

A 1989 issue of the Academy of Management Review was dedicated to theory building. Several seminal articles were included that framed the foundation of theory building to date (Bacharach, 1989; Eisenhardt, 1989; Osigweh, 1989; Poole & Van de Ven, 1989; Van de Ven, 1989; Weick, 1989; Whetten, 1989). Later contributions also supported a joint effort at understanding theory building more deeply (Ghosal, 2005; Gioia & Pitre, 1990; Hambrick, 2007). Most of these contributions either frame theory building from a specific methodological perspective or lack the practical, applied direction to make them useful to a novice theory builder trying to create theory.

Similarly, a collection of articles on theory building was published as an issue of Advances in Developing Human Resources (Swanson & Lynham, 2002). Authors again took a methodological approach to describing theory building in the following categories: quantitative (Lynham, 2002b), social constructive (Turnbull, 2002), grounded theory (Egan, 2002), case study (Dooley, 2002), and meta-analysis (Yang, 2002). Certainly, insights were uncovered, but again the novice theory builder was left with little guidance for actually performing theory building. Torraco (2002) summarized the collection of articles in an attempt to sort out where each approach had highest utility.

The concepts put forward in these collections of works on theory building are important contributions, and they are covered in detail at the appropriate points as this book unfolds. These works are by no means exhaustive of theory-building content, but should be considered required reading.

A THEORY FRAMEWORK

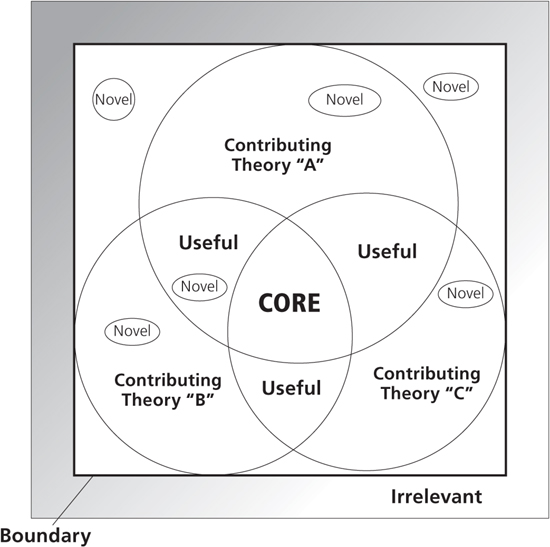

Swanson (2007) established a theory framework that labeled six specific components of theories for framing the boundaries and defining applied disciplines—not just useful subtheories within an applied discipline. The six components are (1) theory boundaries, (2) contributing theory, (3) core theory, (4) useful theory, (5) novel theory, and (6) irrelevant theory (see Figure 2.2):

• Boundary: The boundary of the theory of an applied discipline is established by specifying its name, definition, and purpose along with assumptions or beliefs that conceptually frame the theory and practice of that discipline.

• Contributing theories: selected theories that fundamentally address the definition, purpose, and assumptions undergirding an applied discipline

• Core theory: the intersection and integration of the contributing theories that operationalize the definition, purpose, and assumptions of an applied discipline

• Useful theory: a theory outside the core theory of an applied discipline and within the intersection of two contributing theories that has utility in explaining an important realm of practice within the discipline

• Novel theory: the theory of a narrow phenomenon that is related to an aspect of the applied discipline under consideration that could logically provide an unusual explanation of how the phenomenon works.

• Irrelevant theory: any theory that falls outside the theory boundary, contributing theories, core theory, and useful theory of the applied discipline under consideration with no compelling evidence of its usefulness or logic supporting its potential for a novel contribution

FIGURE 2.2 Theory Framework for Applied Disciplines: Boundaries, Contributing, Core, Useful, Novel, and Irrelevant Components

Source: Swanson (2007a).

The context of these theory components is relevant to applied disciplines. This means that a theory contribution in an applied discipline could be judged as a core theory, a contributing theory, or other. This book is less concerned with classifying the utility of theories and instead is focused on building theories. However, it is still useful to think about the potential role of a theory in an applied discipline before taking on the theory-building effort. For example, a theory of scenario planning might be considered a contributing theory in the applied discipline of strategic management. Alternatively, a theory of motivation might be considered a core theory in the discipline of organizational behavior.

Honing the six theory-framework components is an iterative process. Developing and testing a single component in context of the others will advance a theory as it continues to evolve. Iterations of component refinement should have an eye toward understanding and harmonizing all six components.

Boundary and Irrelevant Components

Two critical components of the Theory Framework for Applied Disciplines include the boundary of the theory component and the irrelevant theory component. These components are particularly important when judging existing theories and their roles in applied disciplines. As applied disciplines grow and change over time, they continue to be messy and diverse. The ability to classify theories can be very useful in the struggles to debate and define core purposes and theories for an applied discipline.

When building theories, however, these components are even more important. Most scholars are drawn toward building novel theories to distinguish their ideas as unique or different. Often the drive for uniqueness results in irrelevant theories. By definition, irrelevant theories make no useful contribution to the applied discipline. Few disciplines and scholars are savvy enough to make judgments about such fringe theories, and it is usually left to debates and time to sort out.

GENERAL CRITERIA FOR ASSESSING THEORIES

Criteria for assessing theories are important because they provide a means by which to judge the utility or even potential utility of a theory. Some authors have tackled the important work of creating a general set of criteria, but there is no agreement, and different authors focus on different parts of the theory-building process with their criteria. Some authors have even proposed a specific set of criteria based on philosophical orientation.

It is important to establish a general set of criteria that can be applied to any theory regardless of philosophical orientation. Theories still must be able to do what they are defined to do, and a set of criteria is intended to give researchers a means by which to judge utility. The following criteria for assessing theory can be used as the basis for assessing theories in applied disciplines (Patterson, 1983, pp. xx–xxi):

Importance. A theory should not be limited to a few situations; rather, it should have relevance to real-world situations. Importance may be difficult to evaluate, as acceptance by professionals or recognition and persistence in the literature may be the only real indication of importance. Also, if a theory meets the other following criteria, then it is probably important as well.

Preciseness and Clarity. A theory should be understandable, internally consistent, and free of ambiguities. Clarity may be tested by the ease of relating the theory to data or to practice, or the ease of developing hypotheses or making predictions from it and specifying methods of testing them.

Parsimony and Simplicity. Parsimony has long been considered an important criterion for theory. This means that the theory has a minimum of complexity and few assumptions. Parsimony carried to an extreme, however, may lead to oversimplification of the theory. Parsimony is important only after the criteria of comprehensiveness and verifiability have been determined.

Comprehensiveness. A theory should be complete, covering the area of interest and including all known data in the field. The area of interest, however, can be restricted to one general area.

Operationality. A theory should be capable of being reduced to procedures for testing its propositions or predictions. Its concepts must be precise enough to be measurable. Theoretical concepts should first be identified and defined and then a method of measurement chosen or developed. Not all the concepts in a theory must be operational. Some concepts may be used to indicate relationships and organization among other concepts.

Empirical Validity or Verifiability. The preceding criteria are rational in nature and do not directly relate to the correctness or validity of a theory. Eventually, however, a theory must be supported by experience or experiments that confirm it. That is, in addition to its consistency with or ability to account for what is already known, a theory must generate new knowledge. However, a theory that is disconfirmed by experiment may lead indirectly to new knowledge by stimulating the development of a better theory.

Fruitfulness. The capacity of a theory to lead to predictions that can be tested, leading to the development of new knowledge, has often been referred to as its fruitfulness. A theory can be fruitful even if it is not capable of leading to specific predictions. It may provoke thinking and the development of new ideas or theories, sometimes because it leads to disbelief or resistance.

Practicality. The final criterion for a good theory, which is seldom mentioned, is whether the theory is useful to practitioners in organizing their thinking and practice by providing an organizing framework for practice. A theory allows the practitioner to move beyond the empirical level of trial-and-error application of techniques to the rational application of principles. Practitioners too often think of theory as something that is irrelevant to what they do, unrelated to practice or real life.

CONCLUSION

This chapter set out to define the term theory, present the differences between models and theories, and describe a variety of types of theories. In addition, we summarized some major philosophical orientations toward theory building and described a set of general criteria for assessing theories. This chapter, along with this book, is meant to be accessible and useful as background information for theory building in applied disciplines. The task has been to present relevant information and avoid esoteric discussions. The next chapter will review the General Method of Theory Building in Applied Disciplines, followed by chapters that give detailed guidance on each of its phases.