CHAPTER

2

Life at the Top

Executives are paid to be paranoid. Executives are territorial. Executives are impatient.

—Harold Fethe

Your success depends on getting through to C-level executives on their terms. Let’s be clear about this—presenting to C-levels (or other senior decision makers in your company) will simply be the most important presentations you will ever make in your entire life. Ever! In your entire life! Think about it. You probably will not go into politics or entertainment where you could be in front of huge audiences at say, the Democratic or Republican national conventions, or on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial speaking to hundreds of thousands of people. Nope. Probably not going to happen.

More likely

Yet your 45-minute presentation in the boardroom in front of a dozen people who are not there to be entertained or inspired could get your project approved, could get you promoted, and could make you a hero to your family and your team … or not.

The toughest audience you will ever face are high IQ, high self-esteem males. The research also shows that high IQ, high self-esteem females are only slightly more forgiving.1 Welcome to C-level land.

Input from C-level executives makes it clear that their expectations are unique. The rules are different at the top, and are often a mystery to mid-level managers. Understanding executives at the top level—their personalities, the stresses of their positions, what they demand from mid-level managers—is key to successful communication in and out of the meeting room. Conversely, not understanding whom you’re dealing with can be career suicide.

People who get to the top have traits that set them apart. They are extremely bright, aggressive, successful Type ‘A’ personalities. Most are males and often Ivy League educated. They are under heavy pressure to produce in a highly competitive environment. Your goals must be in line with their goals: to move the company forward. They don’t have time for pleasantries, diversions, or people who can’t respond quickly to their demands. Here we’ll look at the reality that defines their world.

Warning: this is not a pleasant stroll in the park, and it is occasionally ‘R’ rated.

Alpha Personality “Syndrome”

Life for people at the top levels of corporate America is a competitive, power-driven, dog-eat-dog world. And they know it. Witness Chuck Tyler, physics PhD, who headed up a major Hewlett-Packard research lab back in the early 1980s. With 100 engineers and scientists under him, he proudly quipped to me one day, “I’m the intellectually dominant primate in the room.”

In our research on the personalities of top-level executives, we did a survey of middle management to see how they perceived people at the top. For a period of six months in our training workshops, we had people describe the personalities and business values of their C-level executives. Content analysis of the surveys showed that the top five adjectives used to describe senior leaders were: data-driven, impatient, aggressive, time-pressured, and intimidating. Perhaps these are qualities that boards prize in CEOs, but they probably don’t describe someone you’d like to have over for dinner.

It may be a stretch to say there is an “alpha male” or “alpha female” personality syndrome simply because there is such a wide variety of successful styles among top-level executives. Consider the huge differences between well-known CEOs: Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard (The HP Way); Andy Grove at Intel (Only the Paranoid Survive); Larry Ellison at Oracle (“We eat our young.”); Bill Gates at Microsoft; Steve Jobs at Apple. Yet, it is undeniable that there are commonalities among people at the top. Their idiosyncrasies help to build the companies they founded, but they can also cause pain to people who work for them.

Writing in the New York Times2 on the death of George Steinbrenner, Benedict Carey commented, “Recent research on status and power suggests that brashness, entitlement, and ego are essential components for any competent leader.” Psychologist Kate Ludeman noted in the Harvard Business Review4, “Possessing both intimidating personalities and genuine power, alphas expect the world to show them appropriate deference.” According to Andrew Park in Fast Company5 magazine, “Convinced of their greatness, these alpha males lapse into arrogance, defensiveness, manipulation, and malevolence, leaving a tangle of confusion and unhappiness.”

Why are these descriptors so harsh? Performance pressure, for one thing. CEOs answer to many audiences: shareholders, analysts, employees, customers, management, even community groups. One minute they’re dealing with a Wall Street phone call, and the next minute they’re making an employee video. As we’ll see in Part IV, they describe living in a kind of fishbowl. Ginger Graham confided that she can’t have a bad day and be wearing a frown, or forget someone’s name for fear of sending the wrong message. And that’s just the start of the pressure.

What Job Security?

Why is it a bare knuckles world at the top level? For starters, there isn’t much job security. If you plan to work with C-levels to get things done, be advised they won’t be there for long. According to CLO6 magazine, the average tenure for someone in the “C-suite” is only 23 months.

These statistics are confirmed by Karen Sage, VP Marketing, CA Technologies:

Tenuous job security doesn’t impact just the CEO, but all upper executive-level staff. It’s about holding leadership accountable. Someone has to take the fall. Another situation to note is that most leaders like to bring in people from their past or that are culturally similar to themselves. At the highest ranks, if a new leader comes in they will typically replace half their direct reports. Even if the CEO is promoted from within, the top performers at the next level will be forced to leave 1) because they were passed over and 2) in vying for the CEO position they likely burned bridges competing with the person who passed them over. This is why executives at that level have employment contracts stipulating that if they get fired, they are paid off handsomely.

The Harvard Business Review7 reports that if the company’s stock price goes up after the arrival of a new CEO, there is a 75 percent chance that one year later that CEO will still be in his or her job. But, if the stock price goes down, there is an 83 percent chance he or she will have been fired.

The demand to get immediate results is unrelenting. Few of us live under such daily, weekly, or monthly performance pressure. Rick Wallace says all this goes with the territory: “You’re in a job that can go away or not, depending on how you perform. You’ll keep it or you won’t. If you don’t perform well, you move on. It’s not that complicated.”

But even success is no guarantee. According to Chuck House and Ray Price in The HP Phenomenon, boards ask CEOs: “What have you done for me lately?” Shortly after generating record-breaking profits for their companies, boards fired John Akers, IBM; Ken Olsen, DEC; Ed McCracken, Silicon Graphics; and Rod Canion, Compaq.8

Those looking up to the CEO may see an imposing figure to be admired or feared. However, from the vantage point of the CEO, it’s very different. Ginger Graham observed that CEOs often feel like “hired help.” With shareholders demanding quarterly profits, and a board that understands little about the day-to-day problems of running the company, the CEO may feel like a puppet on a string with little job security.

The Power Culture

According to researcher Adrian Savage, what gets you ahead at the lower levels is competence, but at the top it is all about raw power. In his breakthrough paper “The Real Glass Ceiling,”9 Savage describes the shift that must happen as a manager advances up the ladder:

As he or she crosses the invisible barrier, the rules change. To advance further, s/he must play by the new rules, even though they’ve probably never been explained or even acknowledged openly: succeed in getting and keeping a position of influence and power, from which to secure resources for his or her division or function. Do this amongst a highly competitive group of people who are all outstanding individuals, all working hard to secure their own positions and resources, and all committed to winning first and worrying about any casualties later, if at all.

Shortly after reading the Savage paper, an executive told me this story:

I was giving my quarterly finance report to our top leadership. As had happened on three previous occasions, Mike, a peer from product development, began challenging my numbers in a derisive manner.

I walked over to him, paused, and said: ‘Mike, you do this to me every time I present. I am goddamned sick of it. This is my presentation and I plan to finish it. If you have something to say to me, you can do it after this meeting is over. But for now, I want you to shut up!’

This executive had played college football and presented an imposing figure. He said the room grew deathly quiet. Mike sank in his chair. “As I scanned the room, I could see looks of approval on the executives’ faces,” he told me. “Six months later, I was promoted to CFO. Two years after that, I was president of the company.” Today he is CEO of a 10,000-employee Silicon Valley technology company.

In the C-suite, it is not about competence—that’s a given. It is about power.

Self-Reliance

When you work with the top level, you’re being watched for your leadership capabilities and potential. How savvy are you? How well do you pick up the cues? Can you be political without looking political? Keep in mind, there is no handbook or instruction manual for what to do. For example, the January, 2005 Harvard Business Review noted:

Would-be CEOs can’t expect much help in moving to the top spot. Boards and chief executives will give only the slightest indications of the behavior they expect. They want to see whether a candidate is sensitive to subtle cues and can adjust his or her behavior accordingly. CEOs and chairmen are more likely to test than to counsel.10

A recently promoted sales executive I worked with in a high-tech company felt he needed help in his new position. After a particularly contentious senior meeting, he approached the CEO complaining that he couldn’t get things done without the CEO’s support. The CEO said bluntly, “I don’t have time for this. Okay, yes, you have my support. Now get on with it.” The end.

Another example illustrates what Savage is describing. Dan was extremely talented and had moved quickly up the management ladder. He was on the verge of being promoted to the C-level. He complained to a VP I’d been working with that he’d presented an idea to the CEO and had been dismissed in an offhanded manner. The VP said, “Well, Dan, you know what, the CEO doesn’t give a shit about your problems. He worries about things like shareholder value, what the financial analysts are going to say in their next quarterly report, some employee lawsuit, and a quality problem in the manufacturing facility in Taiwan.”

The VP went on to add, “Now Dan, you may not like that, but it’s not going to change. You may not be cut out to work at the C-level, and that’s okay. There are lots of other places you can work. But if you are going to play at this level, that’s the name of the game. So take care of yourself. The CEO isn’t there to take care of you.”

Looking for Empathy in All the Wrong Places

A study by two University of California psychologists, Michael Krause and Dacher Keltner11 indicates that people at the top of the economic food chain are less likely to be empathic. They are also less able to accurately read the emotions of others. On the other hand, lower-class people are more empathic and better able to read the emotions of others. According to Krause and Keltner, this is because lower-class people are more vulnerable in the unpredictable environments they live in. Hence, they need support from other people more than their upper-class counterparts.

When you’re presenting in a Fortune 500 C-level meeting, you can bet your executive audience is in the upper class. In 2010 the mean compensation for S&P 500 CEOs was $12 million.12 They are less likely to even notice the anxiety on your face, or to empathically acknowledge your job well done. So, be reassured, it is not personal.

From the Harvard Business Review, to high-tech companies, to the Adrian Savage research, a clear picture emerges: the higher up you go, the more self-reliant you must become. We might add to the old axiom: “It’s lonely at the top—and, there’s no help for you up there either.” No wonder executive life coaching has become a $2.4 billion industry.

So what does all of this mean to you as you stand at the head of the big oval table about to deliver a career-defining presentation to a group of intimidating C-levels? The more you know about them, the more successful your presentation will be. First of all, remember that they are under enormous pressure to perform. They don’t have time to chat, so get to the point. As Ginger Graham said, “I don’t need your life story. I want to know why you’re here, then let’s get on with it.” Secondly, if you do get treated in a rough manner, remind yourself that they are dealing with enterprise-wide problems, and the perceived rebuff is not personal.

It is hard not to take being grilled or even chastised by executives personally, especially if we bring childhood unresolved authority issues with us into the boardroom. Too often people enter the C-suite hoping for approval from a kind and loving “father figure.” Such expectations muddy the water and make time-pressured executives annoyed.

The CEO Ain’t Your Dad

If you come in and seem angry or are being a “suck-up” looking for a reassuring pat on the head for doing a good job, then you are still working out your childhood authority issues. When we have to deal with all of that it is just a waste of our time.

—Felicia Marcus

Our attitudes toward authority figures are determined by our childhood experiences with the first and most powerful authority figure in our lives, our fathers.

If you hated your mean authoritarian father, you may then unconsciously transfer that hatred to other authority figures in your life, like teachers, police officers, and bosses. On the other hand, if you had a distant and judgmental father whose acceptance you never got as a child, you may long for that approval from the boss, whomever that might be.

If all this sounds too “woo-woo” to you, hang on. It is very real in the boardroom according to the executives we interviewed. In fact, citing our research on this issue, USA Today ran a cover story about this problem on the front page of the Money section on Father’s Day, June 6, 2007.13

Imagine a presenter at a C-level meeting with a serious authority problem like I just described. He or she, who may be 30 to 45 years old, walks into a room with a large mahogany table. Seated at the table is an imposing group of eight to 10 people in their 60s and 70s who perhaps founded the company, have enormous power, and huge net worths (perhaps in the hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars). If there was ever a time and place for childhood unresolved authority issues to surface, this is it.

This authority problem is so common that several executives expressed frustration over how it shows up in meetings. Whether the presenter is angry and rebellious or pleading for approval, these meetings are not the time or place for those issues to come up.

Ralph Patterson, former Product Line Manager at Hewlett-Packard in San Diego, told me about his aggravation when junior-level engineers came to his meetings looking for approval. Instead of presenting a recommendation based on their expertise, which is what he needed, they would spend a lot of time explaining how they did the experiment or the study and all the problems they had solved. His reaction was to hammer the presenters. “Don’t tell me how you got the data,” he’d say. “Tell me what the data means. We have to make a decision and move on.”

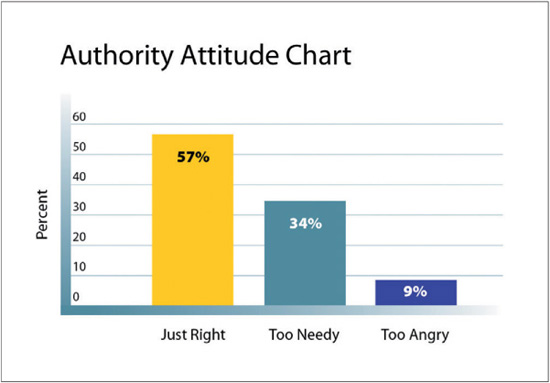

To measure the extent of this problem, I asked our executives, “In your experience, what percentage of people presenting at the C-level have a collaborative attitude, have a needy attitude, or have an angry attitude?” They reported that a surprisingly high number of presenters, 34 percent, are looking for the reassuring pat on the head and are seen as “too needy.” At the other end of the continuum, nine percent come across as angry and resentful. That leaves just 57 percent who have the collaborative attitude the executives value for getting the job done. The people in this last group don’t feel either anger in the face of authority, or a pleading need for reassurance. Their locus of control is within themselves, not projected onto the external power structure around them. They collaborate with the executive team to solve business problems.

Cindy Skrivanek

An excellent example of this comes from Cindy Skrivanek, at LSI Corporation, who speaks to her senior team all the time. She is clear about her role as a resource for decision making at the highest level:

I’m a tool of management. My job is to give senior executives information, lay out a set of options, or maybe ask for a decision … and then leave. I’m not there to be their buddy or to get pats on the back. A presentation isn’t a personal development opportunity or a chance for increased visibility. I’m there to do a job. And that job is to help prepare the executives to make the best possible decisions for the company.

Putting all this together in what we might call an “Authority Attitude Chart,” (Figure 2.1) you can see that only a little over half of the first-time presenters at the C-level handle authority issues with maturity. The executives were clear that these numbers apply to new presenters at the C-level. More seasoned presenters learn through experience how to be successful.

The unforgivable sin is to come in and be arrogant and condescending to your boss. It is shocking how many people will come to me with work that’s a piece of crap, and are arrogant about it … and if I don’t like it that’s my problem.

—Felicia Marcus

Think about your own attitude when you present to the top level. If you are too needy for approval or too resentful of authority, work on moving toward a more collaborative approach. The executives will appreciate it, and you will be more successful.

You are asked to present at the meeting because you have something they need in the decision-making process. “I respect you or I wouldn’t be asking you to be in the room,” commented Brenda Rhodes. Do not be hurt if you don’t get the approval you’d hoped for. Harold Fethe advised, “You may crave reassurance in the meeting, but you will almost certainly get higher marks if you can acknowledge their goodbyes, whether friendly or terse, and allow them to move on to their other work.”

Executive Presence

Business schools do not create leaders. You can only identify leaders. People are born that way.

—Scott McNealy

Co-Founder and Former CEO,

Sun Microsystems

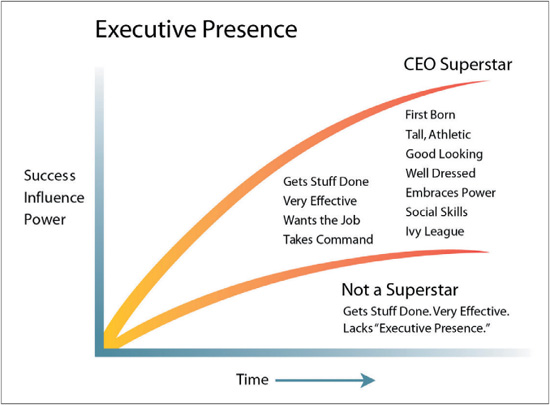

A relatively new concern in the leadership literature is “executive presence.” Executives at the senior levels are all top performers, otherwise they would not be there. Some, though, get catapulted into the top spot. Executive presence plays a big role in such a promotion. Apparently top CEOs have it, and runners-up do not. What, exactly is “it?” What differentiates the stars from the superstars? Executive presence consists of a number of things, some physical, some social, some psychological. To meet Scott McNealy halfway, some of these skills are indeed inborn, but others can be learned.

In his book, The Intangibles of Leadership,14 Richard Davis has an entire chapter on executive presence. Davis points out some of the physical aspects of executive presence: size, good looks, and athleticism. He also includes things that can be learned: speak slowly, walk tall, develop a firm handshake, and have strong eye contact. (The Economist magazine, reported that 30 percent of Fortune 500 CEOs are over 6’2” tall compared to just 3 percent of the U.S. population, and only 3 percent were under 5’7”.)15

Other factors that contribute to executive presence are: confidence, charisma, ability to “own” the room, comfort with power dynamics, and social skills, i.e., the ability to make people feel at ease and feel heard. Think Bill Clinton. An Ivy League education also helps. Birth order may even play a role. A USA Today16 survey, noted that 59 percent of CEOs are the firstborn, confirming Scott McNealy’s assertion.

Don Angspatt, a vice president at EMC, added to this list by pointing out the impact of dress, “A well-tailored image is hugely helpful.”

Don Angspatt

Figure 2.2 shows graphically the difference between the really effective C-level leader who does not become CEO, and the one who does.

Why should executive presence be important to you? For two reasons:

1. It is helpful to know the profile of what defines C-level executives so you know what is expected;

2. If you have ambition to get a seat at the table someday, these descriptors give you a menu of things to work on. (Sorry, can’t be of much help on the height or birth order issues.)

C-Level Backgrounds

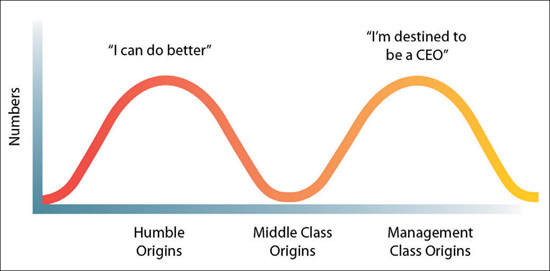

Looking over the class, family, and educational backgrounds of the executives in this study, we could see a pattern that fits a bimodal distribution curve. (Figure 2.3) Although this is not a scientific study, and the sample size is very small, what I noticed is that these executives fall into two quite different groups. One group grew up in very modest circumstances with parents who were not college educated. Others came from executive families with clear expectations about education and business success.

Ginger Graham observed:

Most CEOs I’ve worked with came from modest means. It’s about work ethic and sacrifice, and a desire to have influence and impact. You learn to work against adversity even though you don’t have connections, means, or education. You have to get it done anyway.

Audrey MacLean recalled:

Everything was a struggle. Nothing was handed to me. I didn’t start with an inheritance, and an Ivy League pedigree, or a comfortable office. Everything I did was from scratch.

In one group, people knew early they would be in the world of business, and have executive roles. The other group found the executive calling later in life, usually because of mentors who were not their parents. It may be that people born into families in the middle are simply not that motivated, while those at the top are groomed for it, and some at the bottom are strongly driven to make a better life for themselves.

Only in America

“Only in America are the streets paved with gold,” said Steve Blank’s mother. Steve elaborated, “My mother grew up in a hut. No electricity, no running water. She had to go to the well or the river. To go from that to Silicon Valley is one of those amazing journeys.”

Steve’s parents came to this country in steerage class, through Ellis Island to the lower east side of Manhattan and worked in the garment district. The son of immigrants, Steve started several companies, has become renowned for his entrepreneurial genius, and teaches in the business schools at Cal Berkeley and Stanford. All this in one generation.

California Congresswoman Anna Eshoo’s parents came to the United States as youngsters. Her grandparents fled their native countries in the Middle East due to religious persecution. Anna became a member of the United States Congress in 1993. She said her parents really understood the blessings of this country:

My father never once, in his entire life, complained about whatever he paid in taxes. Not once. If they had guests over to the house who started talking about politics and complaining about taxes, he’d say simply, ‘They don’t realize the blessings of this country.’

Dan Eilers’ father was a truck driver with an eighth-grade education. Dan was CEO of three successful companies, and became a venture capitalist.

Ginger Graham grew up on a dirt farm in Arkansas. Her father was a rural mail carrier. She went on to get an MBA from Harvard, became CEO of several companies, taught at Harvard, and is a member of the Walgreens Board of Directors.

Felicia Marcus was raised by immigrant grandparents, got an undergraduate degree at Harvard, then earned a law degree. In her early 30s she was appointed by Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley to head the largest public works department in the country.

Brenda Rhodes grew up on a sugar beet farm in the state of Washington. She went on to found and become CEO of Hall Kinion, a very successful outplacement company. When she took her company public, Montgomery Securities said it was the most successful IPO of the year, raising $80 million.

These executives’ stories rest four-square in the middle of what we call “The American Dream.” They are bright, talented people who worked very hard to get where they are. Their stories attest to the remarkable opportunities this country offers. So as you address the people around that big oval table, keep in mind some of them may have remarkable backgrounds like these. They will likely appreciate the initiative you show.

Summary

• Are you a “tool of management,” to use Cindy Skrivanek’s concept? That is, are you clear that your role in top-level meetings is to help extremely talented, highly-stressed people make good decisions fast before moving on to the next decision?

• Do you realize that you may be treated dismissively and have your time cut in these meetings by people who are concerned with a lot more than you may even be aware of?

• Do you understand your presentation is not about getting a pat on the back or making friends with the executives sitting around the table? Or even, for that matter, getting a career boost?

• Are you capable of giving executives empathy about the lack of job security and unrelenting performance pressure that govern their lives?

If you can answer “Yes” to these questions, then you’ve captured the essence of this chapter. Gaining these insights about what life is like for people at the top gives you a huge advantage as you prepare and deliver senior-level presentations in the future. You are competing for limited resources with other mid-level people who also have good ideas. Your edge is that, as Sun Tzu says, you “know your enemy and yourself.”

Part I Summary

In Part I, you met the executives of this story who serve as both the foils for our mid-level managers (whom you’ll meet in Chapter 3) as well as their mentors. Your key takeaways in this book will be the strategies our managers learn as they struggle in their top-level presentations.

You also met Dick Anderson, the general manager of Hewlett-Packard’s Computer Systems Division in Cupertino. Remember, I didn’t get what I wanted from him in that meeting. To confirm my memories of all this, I located Dick, who has retired to his ranch in Utah. He reviewed this manuscript and had some thoughts about our meeting back in 1983, as well as about the role of the CEO:

Dick Anderson

The C-level can give you three things: time, money, and energy. What you really want from a CEO is his or her energy. It takes energy to accomplish anything. CEO energy takes many forms: creative thought energy, the energy to create a compelling vision, the energy to articulate a vision, the energy to convert nonbelievers, the energy to reward achievement, and the energy to lead.

If no energy is expended, then nothing happens. It is easy to allocate a few bucks to some well-intended project, but if the project is not in line with where the boss is headed, it won’t go anywhere. On the other hand, if an initiative is parallel to and supportive of the leadership’s directions, the boss will add energy and use your initiative as one more engine to drive for success. Everybody wins.

I saw quality as a compelling issue that needed more than my time, attention, or a few bucks for programs. It needed my energy. I also knew it would have to expand beyond my division and even beyond HP. In our meeting, I must have concluded that you didn’t show me how a few bucks in training could really move our quality results forward.

There you have it. Dick Anderson had a big vision about quality, had been in the national media about the issue, and was looking for someone to help him move his agenda forward, but it sure as hell wasn’t me. As a business neophyte, I was clueless about the bigger vision our GM had. My one exposure to our most senior executive went nowhere.

The rest of this book delves deeply into the issues facing senior-level people so that you will, unlike me, “have a clue” when you walk into that presentation room. You will hear from them what works and what does not work when you present at their meetings. You will learn critical skills about how to put a presentation together, as well as how to survive in a fast-paced senior meeting that you cannot control.