5

Becoming More: Developing Yourself as a Social Leader

I am not what happened to me, I am what I choose to become.

CARL JUNG

Some years ago, one of the authors was working with the CEO and his team in a well-known pharmaceutical company. The problem was Colin. The senior vice president of research and development, Colin had previously been a member of the management team of a small but successful pharma R&D start-up before it was bought by this global organization four years earlier. Although he was happy when the deal went through, Colin was now struggling in his role in the large global corporation. He had acquired a reputation in the short time after the acquisition as being unapproachable, which is clearly at loggerheads with one of the competencies the company defines for his role—an “open and collaborative attitude.”

The head of talent recommended that Colin work with an executive coach, which he did (although reluctantly). The results after a year were disappointing, though not for lack of effort. Colin tried to incorporate some behavioral changes that the coach recommended, such as trying to look approachable at meetings, keeping the door to his office open, and asking inquiring questions of others. After six months or so, he felt he was appearing stilted and awkward, as though he was doing what was not core to him. In short, he felt he was faking it.

Now, there is no doubt that some of these corrective behaviors might have helped Colin in the short run to improve others’ perceptions of him. But these corrections weren’t sustainable; maintaining behaviors that do not have an origin in who we actually are is difficult and over time can be seen as inauthentic. Behaving in a way that was foreign to him only made Colin seem even less approachable and further eroded others’ views of him.

BECOMING THE SOCIAL LEADER

Colin’s story will be familiar to any of us who have been given a list of new behaviors that would help us “improve.” The organization wanted Colin to change his behavior and become more approachable. Colin tried, but could not hold it up in the long run. Something inside him was not in tune with the changes he was trying to make. Does that mean that Colin is doomed to remain “unapproachable”? No.

What Colin needs to do is become aware of the productive conversations, actions, and behaviors (CABs) that are already a part of him. He can start by looking at the root issue: What problems are his perceived lack of approachability causing? Colin can then extend the volume and scope of his productive CABs to address the difficulties his lack of approachability is causing. So, Colin is going to overcome a behavior pattern not by trying to mold himself to a fixed organizational competence, but by expanding and adapting his own repertoire of conversations, actions, and behaviors. Think of jujitsu as an alternative to boxing!

We are aware that we are sidestepping one of the dominant practices in the field of leadership development: the competency development model. Leadership competency models look great on paper. We believe, however, their fixed and retrospective nature makes them fraught with peril in the Social Age. Instead, we propose the following:

- You can improve your capacity to lead successfully in the Social Age by increasing the volume and scope of the productive conversations, actions, and behaviors that are already part of you.

- You can help yourself grow in this way by purposefully approaching challenging situations.

- As growth tends to favor the prepared mind (with apologies to Louis Pasteur), your focus must be on preparing your mind for growth.

TECHNICAL VERSUS ADAPTIVE APPROACHES

For many years now, the state of the art in developing leadership talent has focused on what has been called “competency development.” Competencies became the byword for all things about leadership development, and this approach has spun out an entire consulting industry. Competency development was (and still is) performed in a very targeted manner by focusing on identifying and “improving” specific, company-centered behavior patterns within individual leaders, regardless of whether these new behaviors have any resonance with the individual leader. This approach falls into the category of what Ron Heifetz from the John. F. Kennedy School of Government referred to as solving a “technical problem.”

Heifetz differentiates between technical problems and solutions, and adaptive problems and solutions.1 Technical problems involve very specific, limited, and identifiable challenges and have very limited, identifiable, and direct solutions. Adaptive problems, on the other hand, involve looking at complex phenomena and require long-term adjustments to fundamental aspects of the situation.

Heifetz uses the example of high blood pressure. There are two approaches you can take to resolve this problem. Solving it as a technical problem may involve taking medication regularly to lower your blood pressure. This provides a direct solution, addresses the problem directly, and can in the short term improve the situation. Alternatively, high blood pressure can be addressed as an adaptive problem. In this case, you may look to adjust your lifestyle—changing your eating habits, increasing your physical activity, and reducing your stress level. Addressing high blood pressure as an adaptive problem is more difficult, involves “growing” who you are as a person, and requires making changes across several areas of your lifestyle. This solution, however, also brings long-term benefits and substantial continuous improvement in your health.

Now let’s look at how such solutions relate to leadership. Colin’s real-life example shows him trying to fix a problem by using a technical solution. Let’s look, instead, at how Colin might apply an adaptive solution. We begin by recognizing that there is a problem with others’ perceptions about Colin’s approachability. Our advice to Colin would be that he start by looking at areas of his performance where he is effective and productive. For example, we noticed that when Colin took on a task, he was extremely passionate about it and had a talent for seeing details that often escaped others. He was able to connect the dots faster than the others and pick holes and see around corners. In short, Colin had a real eye for detail.

One of the reasons people saw Colin as less than fully approachable was that he listened to them extraordinarily intently—he was utterly wrapped up in the details of what they were saying. So Colin needed to become aware of his CABs during those conversations. Instead of just focusing his attention on the content he was receiving, he had to expand that attention to the person who was in conversation with him in a way that was uniquely authentic to him. As he started doing that more, Colin began to change others’ perceptions and they started seeing him as interested and committed. No one had to “fix” Colin’s problem of lack of approachability; the problem corrected itself as Colin learned to adapt his CABs. Developing approachability for Colin was not about “walking the talk” or other such slogans, but about taking what he did well—focusing on detail—and expanding that to include the person as well as the task. That is authentic growth!

LIGHTBULBS AND LIGHTNING BOLTS

It is time for a small thought experiment. This will require you to picture four different things and describe them.

- Picture a lightbulb. Describe it. What words come to mind? Bright, illuminating, useful, controllable, predictable, boring?

- Now picture a lightning bolt. What words come to mind now? Bright, illuminating, powerful, dangerous, unpredictable, exciting?

- Think of the last time you were in a classroom of any sort. This could have been in school, at a corporate training event, or in front of a computer for online training. Describe the experience. Are the words you used more like those used for a lightbulb or a lightning bolt?

- Finally, picture the last time you took on an assignment where you had no idea how to begin or how to succeed. Describe it. Was it more like a lightbulb or a lightning bolt?

Reconciling the learning impact of an experience versus controlling the content of learning has been the dilemma facing leadership development for more than half a century. Trying to help people become leaders by placing them in a classroom has some distinct advantages—the time is focused, you know what the expected outcomes are, and you can create awareness and even inspire people. Also, no one gets fired, so it’s a great safe environment. However—and it’s a very big however—no one really learns to be a leader that way.

On the other hand, put people through the crucible of a career-making experience, and they will certainly learn an approach to leadership. However—and again, it’s a big however—you have no idea what type of leadership they are learning. And sometimes people fail and get fired.

In a series of research experiments performed in the 1970s, the influential psychologist Albert Bandura demonstrated two important things. First, he discovered what was so eloquently stated by the great wit Yogi Berra: “You can observe a lot just by watching.” The second thing Bandura discovered is that, while observing can teach you something, the knowledge does not become part of you unless you use it successfully in real circumstances. This led to an approach that we call “learn–then do,” a combination of learning in the classroom, followed by attempting the practice in “real life,” then getting feedback. Seems a lot like a lightbulb.

The Problem with Muscle Memory

Martin Seligman applied the physiological concepts of tonic (muscles at rest) states and phasic (muscles in action) states to explain why it’s so difficult to predict performance.2 According to Seligman, just as measures of electrical impulses in muscles are not directly relatable from their resting state to their in-motion state, assessments of behavior and performance made in a “tonic” state—such as tests, interviews, or classroom have only a limited relationship to behavior and performance in a “phasic” state—when the person is actually engaged in performance.

Similarly, learning and development in the lightbulb or “learn then do” mode has a limited utility. In this mode we tend to develop automatic scripts—muscle memory—that we fall back into mindlessly every time we are faced with a situation or problem that we believe we have dealt with before. Leaders are encouraged to follow these steps whenever they recognize the situation. This is the essence of the athlete’s motto, “Don’t think, react.” This approach to development seeks to create leadership muscle memory, with leaders reacting to situations with common, predetermined, preapproved behavior patterns.

We find there are two significant challenges with this approach. First of all, life is much more diverse and unpredictable than the events that arise on a football field or a tennis court. Although the number of situations confronting a leader may be diverse, as behavior patterns become more ingrained and automatic, it can become difficult for a leader to recognize nuances in situations where the old patterns do not apply. Worse still, relying on rote patterns of behavior encourages a lack of adaptation and flexibility.

Secondly, this approach encourages leaders to adopt behavior patterns that have been created outside themselves, as was the case with Colin. These behaviors may or may not be consistent with the way the leader sees himself and with who he really is. Inauthentic behavior patterns can be difficult to sustain, create barriers to relationships, and cause stress in the person trying to maintain an approach that she does not see as “hers.” All of this may further lead to cynicism, frustration, and a lack of effectiveness.

As we have discussed, authenticity is critical to sustaining an approach over the long term. Rather than trying to grow as a Social Leader by adopting a number of automatic responses to specified situations, expand your portfolio of productive conversations, actions, and behaviors (CABs). These expanded CABs need to be both consistent with who you are as a person and engage the range of activities required to lead in the Social Age.

At this stage we need a lens through which we can focus on our effective and productive CABs: this is the lens we gave you earlier in the Tenets of Social Leadership. Each of the five tenets provides the space and channel to grow your CABs.

- Being mindful

- Proactively influencing the world around you

- Authentically relating to others

- Being open to new information and adjusting perspective

- Adjusting approaches for different audiences—social scalability

Growing these productive capabilities requires an approach that is personally meaningful, insightful, and focuses on development that is unique to you. We find that, rather than a “learn–then do” approach, this requires a “learn–while doing” approach. But remember not to confuse the “learn–while doing” approach with the “do then hope” approach, where you jump into a situation striving for success (or just survival) and retrospectively try to extract meaning! In the learn-while-doing approach, you take on new, challenging situations with a growth intent. We will explore this approach by discussing ways of turning lightning bolt experiences from do-then-hope moments to learn-while-doing opportunities.

SEMINAL EXPERIENCES

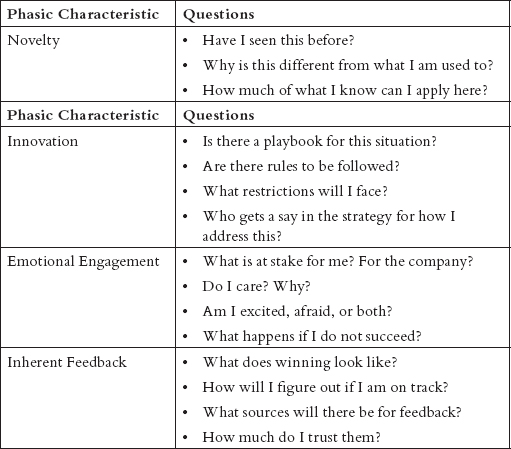

As we discussed in the last chapter, “seminal situations” render our normal way of responding insufficient. New challenges confront us and we find ourselves in deeply unfamiliar waters. Seminal situations involve four features: they are novel, are energizing, allow for “behavior innovation,” and give us feedback on success and failure in the moment.

1. Novel. Novelty is the experience of being suddenly thrust into a situation that demands mindfulness. Our automatic ways of behaving, our “mind-less” patterns of reacting, are simply insufficient to deal with the situation at hand. We find ourselves struggling at first to understand the nature of the challenge and are even at a loss as to how to proceed.

Novelty may arise from changes to:

- Content—the substance of the challenge; dealing with a challenge in a new functional area, for example

- Context—where the experience is occurring; dealing with a new region, location, or department

- Scope/volume—a significant increase in the range of impact of the challenge we are facing

2. Energizing. Seminal situations fully and deeply engage our interest, our excitement level, and our passions. These are situations in which we find ourselves struggling but motivated by the struggle. Something meaningful is at stake.

3. Allow behavior innovation. Seminal situations are those in which the proper path is not laid out before us. There is no best practice playbook to open up and there is no script to be followed. Others may have walked this road before us, but we are required to walk it in our own way, inventing as we go along.

4. Give feedback on success and failure. We win, we lose, we make progress, then we lose ground again; all of these may occur as we work to resolve the challenges of this seminal situation. True seminal situations are those in which we are able to gain feedback on the success and failure of our CABs. Sometimes our ability to gain feedback is inherent in the situation, and other times we must work hard to set up opportunities for feedback. Either way, feedback allows for the constant course correction necessary to understand which of our innovative actions are moving us forward to address these novel challenges.

THE LIGHTNING BOLT

Ever since Morgan McCall and Michael Lombardo published their critical study Lessons of Experience,3 the power of developing leaders through direct experience has been recognized and seen as essential. We know how to set up seminal situations: significantly change either the content of what a leader is doing, the context in which he is doing it, or his scope of responsibility. Or perhaps change two or all three of these. Limit the constraints on what he can do to succeed. Ensure there is something real at stake and be sure he will know if he is succeeding along the way. We have been throwing people into the deep end of the pool for many generations. The ones who don’t drown seem to come out better. Is that all there is to it? Not really.

These types of experiences are certainly seminal experiences as they contain all of the characteristics of seminal experiences we have previously discussed. These experiences are truly lightning bolts: bright, illuminating, exciting, and powerful … also dangerous and unpredictable. Recall the last time you were in a situation like this. As likely as not, you were in survival mode, doing whatever seemed best to survive the challenge and come through to the other side.

Do you learn from this? Certainly, yes. Do you grow as a result? Sure—just ask the dozens of people to whom you have told your heroic story over and over. But what did you learn and how did you grow? You may never fully know. In some respects, you will have grown the productive ways in which you lead. Maybe some approaches were so idiosyncratic to surviving that experience that you are likely to fail whenever you resort to them in other situations. And some of the CABs you leaned on to survive that experience may have proven destructive everywhere else. We refer to these situations as thought-less seminal experiences.

We suggest an alternative approach, which we refer to as thought-full seminal development. Have a look at the chart below.

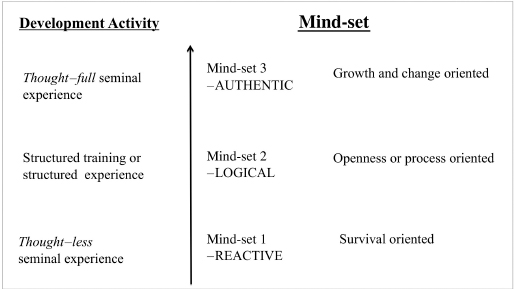

FIGURE 5-1 Development Mind-Set

Mind-set 1 represents a thought-less seminal experience in which the individual operates in a reactive mode with the primary task of survival. It is a lightning bolt experience that will change the leader—but how much of the change will be productive is an open question.

Mind-set 2 represents a structured experience with a logical mindset, allowing you to “master for the moment” a very specific set of behaviors in a controlled stable environment. Very much a lightbulb experience, it treats leadership as a technical problem. Will the specific behavior patterns imparted help you grow as a leader? It depends on the extent to which the behavior patterns you are being exposed to align with your authentic self and with the Tenets of Social Leadership. Will this be productive? Once again, it will depend upon how rigid your muscle memory tends to become. Will you be able to remain mindful and recognize when innovation is needed? We don’t know.

Let’s now look at the third way, what we call thought-full seminal experiences, represented by Mind-set 3. In these experiences, the individual approaches the challenge with a learning mind-set and an expectation of growth and change.

Thought-Full Seminal Experiences

Thought-full seminal experiences begin with three things:

- Self-awareness

- A seminal situation

- Purposeful intent

Self-awareness involves knowing and owning your productive and unproductive aspects of the Social Leadership tenets and the CABs these lead you to undertake. In the previous chapter we discussed tools and approaches that will help you understand yourself as a Social Leader—use these tools to cultivate your approach in relation to the five Tenets of Social Leadership and recognize which of your CABs are productive, which are not, and why.

Seminal situations, as we discussed earlier, involve novelty (usually in the form of changes to the content, context, or scope that the leader is dealing with), emotional engagement (the leader cares about what is at stake), opportunity for innovation, and inherent feedback. Not every significant experience leads to a seminal situation. Some experiences require effort so that they become seminal, while others are important events but not seminal situations. When a significant event does occur, for example a promotion, relocation, or the need to clean up after a major failure, ask yourself the questions below.

Use the answers to these questions to either enhance the situation, bringing it to the level of a seminal situation (one with real developmental possibilities), or to decide that this is a situation with limited developmental possibilities. For example, you may find that you need to negotiate a wider field of possible actions or identify a few trusted people from whom you can gather feedback along the way. Alternatively, if you truly do not care about the outcome of a situation, it is unlikely that it will impact you in a meaningful way.

Purposeful Intent

Purposeful intent refers to deciding early on that this challenge/event/opportunity in front of you is one you will use to expand your leadership capabilities. Once you make that decision you will engage in two actions, based on the Social Leader Learning Arc. The first involves setting up the conditions to create a learn-while-doing leadership growth opportunity out of the situation. The second involves creating a mindful intent to learn. We will discuss how to use the Social Leader Learning Arc to do both.

SEMINAL EXPERIENCES IN APPLICATION

In the previous chapter we introduced the idea of the Social Leader Learning Arc based on Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey.4 Here we will revisit this Learning Arc and use it as a tool to set up thought-full seminal development experiences.

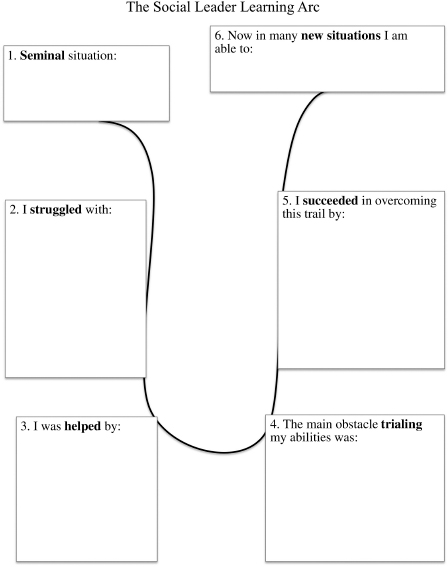

FIGURE 5-2 Learning Arc Icon

If you remember, we used the map above to help chart your learning from past experiences.

In this way, we treated past seminal experiences as thought-less development experiences, assuming that there was no development intent and that the results of these life experiences helped to build your repertoire of both productive and nonproductive conversations, actions, and behaviors. Essentially, we suggested using the Social Leader Learning Arc to examine past seminal situations to extract meaning. Learning your characteristic CABs help you make judgments about which are productive and which are nonproductive.

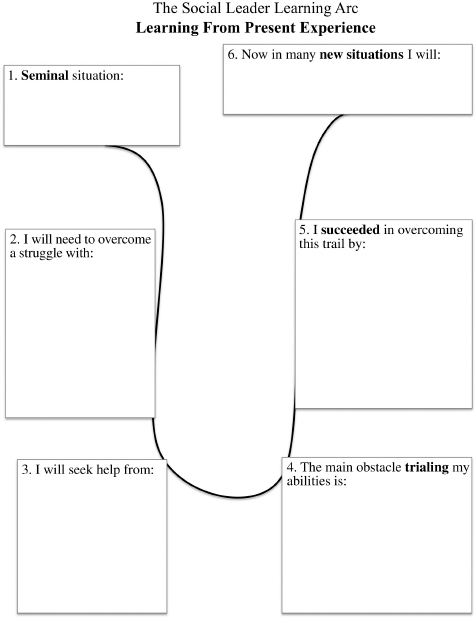

FIGURE 5-3 Prospective Learning Arc

We now introduce a few changes to this map to turn it into a proactive development tool. Have a look at the Social Leader Learning Arc on the previous page.

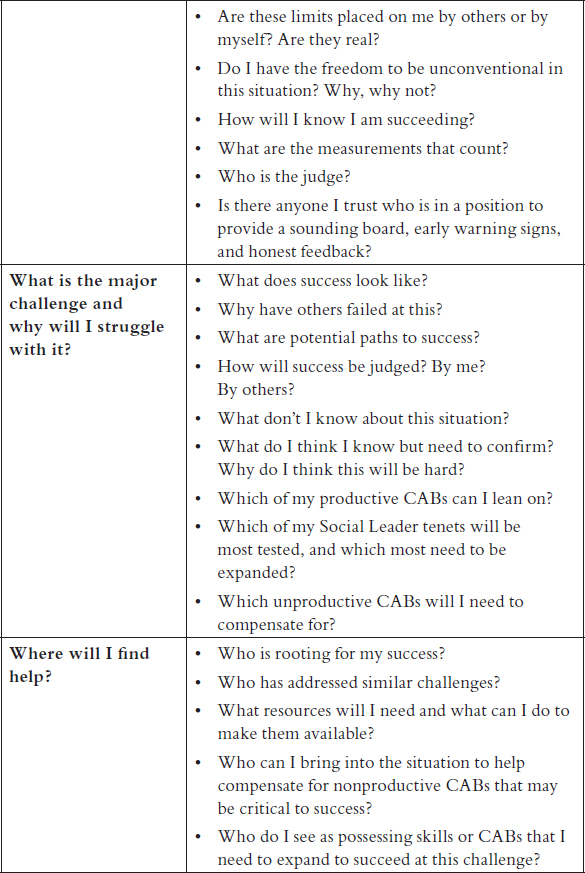

Addressing the first three items in this map: situation, major obstacle, and sources of help are part of creating growth intent. These are the questions to answer before jumping into the situation. The table that follows lays out the questions to ask in order to be mind-full about what you are stepping into. Note that these questions presuppose self-awareness, that is, they assume you have a good understanding of yourself as a Social Leader. Having thought about the productive and nonproductive CABs that are part of your repertoire within the Tenets of Social Leadership will enable you to ask and answer these questions honestly.

Answering these questions will help you enter into this seminal situation prepared to grow, with some early pointers on assistance and support. This is the planning portion of a thought-full seminal experience. Taking action on these three parts of the Social Leader Learning Arc enable, but do not create, the learn-while-doing experience you are trying to establish.

Once you have considered these elements of the Learning Arc, it is time for mindful engagement. While you work to overcome the main challenge of the seminal situation, you will need to actively and regularly engage in the next two steps of the Learning Arc, which require that you consider these questions:

- What challenges or obstacles are putting my abilities to the test?

- How am I succeeding?

MINDFUL DEVELOPMENT: UNDERSTANDING LEADERSHIP TRIALS

Seminal situations, as we have noted, are defined in part by the need for “behavior innovation.” Behavior innovation means having conversations, taking actions (making decisions and setting policy or strategy), and using behaviors that are not normally part of your comfort zone. These new CABs are required because the overarching challenge of the seminal situation and the smaller challenges along the way—leadership trials—will be those you have either not seen or not successfully confronted before. Approaching these trials with a growth intent means that you are striving to remain mindful in the situation—diagnosing what is going on, while it is going on.

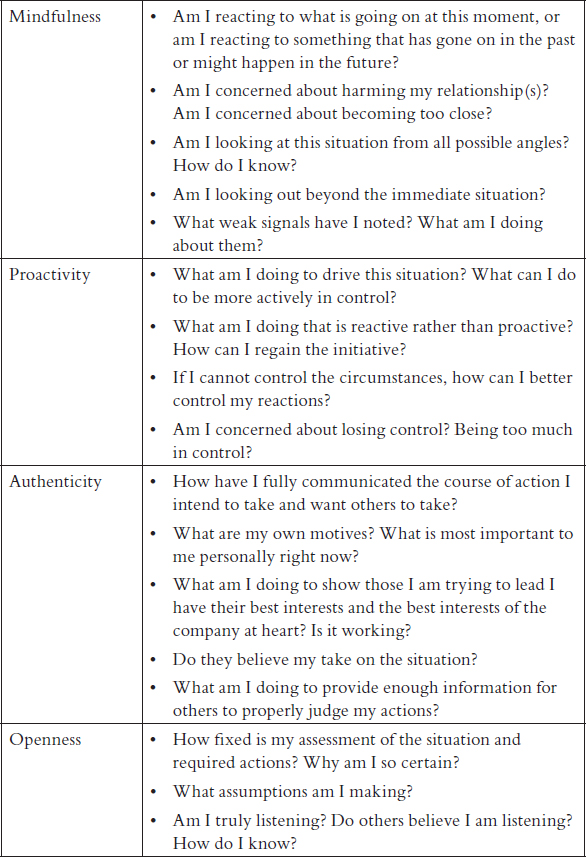

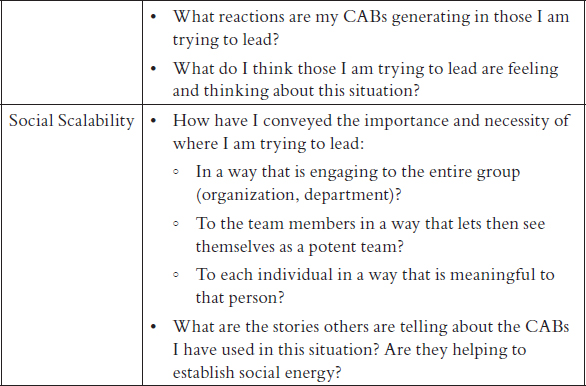

When you find that you are struggling to lead successfully—that is, to influence and direct the attention and effort of others—look at the situation through the lens of Social Leadership. Keep the diagnostic questions that follow in mind as you determine within which tenet you need to innovate.

Keeping these questions in mind will help you see where your leadership strengths are having a positive effect. Hopefully, after using the tools in the previous chapter to understand yourself as a Social Leader, little of this will come as a surprise. Using these questions to be mindful about your success as it is occurring will also provide clues to areas of leadership in which you are not being productive. Look at the areas you believe are limiting your effectiveness and consider which CABs you are using within that tenet. Now is the opportunity for innovation.

Take a hard look at the CABs you normally rely on within this tenet and which you are using in this situation, then take three actions. First, go to the sources of feedback you set up during the “help” planning, and confirm (or expand) your assessment. Do this in real time, while the situation is unfolding and you are asking yourself the questions above. New York City’s successful and popular mayor in the 1980s, Ed Koch, was famous for constantly asking the question, “How’m I doin’?” That approach helped him earn three terms as mayor and have a bridge named after him.

Second, consider alternative CABs that can be used to compensate for the lack of success in this situation.

- Use the self-assessment work you have already done and consider again the list of productive and nonproductive CABs in the appendix.

- Look carefully at the chapters that follow in part 2 that deal with the tenets in which you are not productive to learn how to expand your productive capabilities in these areas.

- Reach out to some of the resources you planned for in the “help” step of the Learning Arc.

Before engaging in these new CABs, take a moment to decide if they really are authentically you. These may be approaches you have not tried or even thought about trying before, and that’s fine. In fact, it is the whole point of behavior innovation.

The real question is, are these new CABs consistent with who you believe you are and how you see yourself? Or are they recommendations from others that fit more with their approach than yours? If it is the latter, it will be difficult to sustain them over time and, worse, may erode others’ perception of you as authentic. Remember, compensating for a nonproductive area of your leadership with a strength is much more likely to succeed than attempting to “correct” this nonproductive aspect with CABs that are simply not you. Finally, remember that, at times, compensating for a nonproductive area of your leadership can mean bringing into the picture someone else to take on those CABs for you.

Finally, it is time for step 6 of the Social Leader Learning Arc: “In many new situations I now will …” This is the time for reflection about what you might do differently. Once the seminal experience has wound down, it is time to look forward and consolidate the changes and growth in leadership productivity you have made. Approaching this experience thoughtfully with a growth intent and working through the steps of the Social Leader Learning Arc will give you a solid understanding of the CABs in each of the Tenets of Social Leadership that helped you successfully navigate the challenges you faced. The task now is to examine these CABs and identify the aspects of the situation that made these successful.

Rather than focus on the specifics of this situation, generalize the pattern within the situation that leads you to this specific CAB. For example, you may have found that three key players needed to work together as a team for the first time in order for the project to be successful. While ignoring this at first, you realized that you could rely on some of the CABs you use to create affiliation with individuals and scale them for a team to create needed cohesion. Generalizing beyond this specific situation, you now have some experience with the CABs needed to create relationships among a team, and these can be used whenever you see the need for tighter cohesion. Going forward, you may be more attuned to seeing cases where team cohesion is needed.

Once you recognize the new CABs that have proved effective and the patterns within a situation that make them relevant, you can answer the last question in the Social Leader Learning Arc and begin to extend your leadership capabilities. This approach to development through thought-full seminal experiences is one to be repeated over and over again as you grow as a Social Leader. It starts by being aware of your leadership capabilities, seeking out seminal situations, approaching them with a growth intent, and then working to authentically extend your productive CABs within this situation and planning to generalize them beyond this situation.

IN SUMMARY

We refer to development as becoming more. Rather than create new capabilities where none exist, we recommend instead that you grow the productive capabilities you possess and expand the situations in which you apply them. This journey begins, of course, with knowing yourself in relationship to the Tenets of Social Leadership. True development comes from balancing lightbulb experiences—focused and planned, with lightning bolt experiences—engaging and meaningful. We call these types of experiences thought-full seminal experiences. This chapter has provided a guide to help you identify and/or create thought-full seminal experiences to aid your growth. Further, the Social Leader Learning Arc that you used to document past experiences in chapter 4 can also be used to help get the most out of thought-full seminal experiences. As you approach your own development, it is crucial to consider the mindset that you bring to the effort. An “authentic mindset” is one that begins with the intention to use an experience to grow, and an openness to rethink the conversations, actions, and behaviors you reach for to address different challenges. Bringing this mindset to a seminal experience is a powerful “learn while doing approach.”

SUMMARY OF PART 1: “CAN I GET THIS ON ONE PAGE?”

In a world where newspapers have become blogs, video has been shortened to Vine clips, letters have become instant messages, and opinions are expressed in 140-character tweets, our challenge as authors is to put this part of the book onto one page. Here we go.

The Social Age is here, replacing all that has come before. It is a world driven by socially created information, networked communities, and the prosumer. The new realities of this world are that knowledge is a commodity, the community is replacing the hierarchy as our primary organizing structure, and cheap communication and socially created information are accessible to all.

Along with all of the amazing benefits of this Social Age come a number of challenges, including:

- Constant disruption from difficult-to-forecast events

- The need to remain proactive in the face of ambiguity created by complex events born of independent, intertwined, emergent forces

- A change in audience; the community—composed of networks tied together through interest and passion—has become the defining unit to be addressed

- Information and meaning created constantly, communally, and in real time

- Easy access to global communication, which has given everyone a megaphone and made the crowd the editor of mass-distributed content

These challenges transform the work of leadership; rather than creating meaning and control, leadership now means harnessing Social Energy. We call this Social Leadership, and it demands that you think of yourself more like a mayor than as a general.

Social Leadership is not defined by a list of traits or characteristics. Rather it is a lens through which to view the conversations, actions, and behaviors (CABs) that are authentically part of the leader and are productive in harnessing Social Energy. We call this lens the Tenets of Social Leadership and there are five areas to explore, corresponding to the five challenges of the Social Age. The five Tenets of Social Leadership are:

- Mindfulness

- Proactivity

- Authenticity

- Openness

- Social scalability

Becoming a Social Leader is not about changing who you are. In fact, remaining true to yourself—being authentic—is crucial. Becoming a Social Leader is about becoming aware of your productive CABs within each of these five tenets and then expanding how you use them.

The process of developing oneself as a Social Leader involves understanding who you are in terms of these tenets—what we call your Personal Narrative—and then seeking out what we call having mindful seminal experiences. These experiences allow a learn-while-doing opportunity and need to be actively created and seized. We have provided a tool to assist with this process, called the Learning Arc, which offers a way to look at past experiences and uncover your Personal Narrative as well as a way to cultivate a growth mind-set for approaching current and future seminal experiences.

This summary is a bit more than one page but, like many leaders, we are immigrants to this new Social Age and are still learning.

Let’s turn now to each of the challenges of the Social Age and look at how mayor–leaders use the Tenets of Social Leadership to address these challenges and at the conversations, actions, and behaviors that will be productive in addressing them.