1

Leading in the Social Age

Lead from the back, and let others believe they are in the front.

NELSON MANDELA

In 1995, the commercial Internet came into existence and the world ended and was reborn. This is not an overly dramatic statement. If you are over thirty-five years of age, you learned to think and work in a world defined by planning for foreseeable trends and competitors. That world has been completely replaced by the Social Age—a time marked by digital connectivity, socially created information, and globally connected networks where constant disruption, agility, and competing points of view are the rule. If you are less than thirty-five years old, all you know is the Social Age. You joined the world of work in the twenty-first century and only know a world where the Internet and social media are part of life. You are native to this world and everyone else has immigrated to your world, bringing with them ways of thinking and leading that don’t quite fit.

Let’s take the example of Julia—a digital immigrant struggling to make the shift. Julia is the global head of strategy for a well-known telecom company in the United Kingdom. She is talented, in her forties, and has earned her place in senior management. With a track record of driving change in her past three organizations, she is now working in a corporate role. Many of the teams that report in to her are spread across the world and loosely linked together. Julia thought she knew all about managing a matrix and understood that she had to drive the corporate marketing vision and strategy across the regions and the local markets. She gathered her regional marketing heads at an off-site meeting to explain the company’s new strategy to all of them and share the vision of the top team. She gave them lots of detail on how regions would provide information to the center, what the numbers were to look like, and, most importantly, the key processes that would make sure the matrix worked.

A year later Julia was starting to realize that she hadn’t gotten the traction she wanted. In one particular region there was a young marketing head named Dmitri who had tweaked some of the core messages that came from her office and developed a marketing campaign using a local celebrity that clearly did not fit with the global marketing message. But the campaign was a big hit and the region was doing very well. Julia struggled with balancing the need for order and consistency with the corporate message and the need to manage employees like Dmitri. She congratulated him on the new campaign but asked him to henceforth report to her on every decision he made, and made it very clear that from now on, no campaign was to be launched without her approval. Dmitri soon left the company, and the numbers in the region began to dwindle. Before leaving the company Dmitri logged onto Glassdoor and made sure that he expressed his views on what was wrong with the organization.

Julia hadn’t even heard of the “Glassdoor thing,” as she called it when the head of HR brought it up at a Monday morning meeting. He connected to the website and displayed Dmitri’s comment on the LED TV screen at the end of the room: “… good company to work for but there is zero culture of innovation. Managers like employees to do what they are told to do, and any attempt at thinking on their own or being creative is disallowed.”

“But surely we have to enforce discipline and standard procedure across all regions!” exclaimed Julia when one of the meeting participants referred to the need to understand people like Dmitri. “We cannot be held ransom by anyone …” agreed Paul, the head of finance. Julia was struggling with the Social Age and she was playing by the book.

Julia saw in Dmitri an employee who was “refusing to play ball.” If only she had been able to step into the shoes of a Social Leader, Julia would have found a way to reconcile Dmitri’s passion for his market and his constituencies with the fact that a global strategy was essential to the company. Dilemmas such as these are exactly what complexity is all about. Rather than attempting to solve them in a linear, top-down fashion, Julia needed to explore complex solutions arising out of the conversations, actions, and behaviors characteristic of the Social Age.

Sally Shankland is the CEO of UBM Connect, one of the companies in UBM, a global marketing and events management company, and also heads the social and culture function for UBM Global. She has been working at UBM for twenty-five years, making her way up from an entry-level marketing role. Astute, authentic, and compassionate, Sally is the epitome of a leader who has made a successful transition into the Social Age. She talked to us about how, just fifteen years ago, she led differently and her need for control dictated how she ran meetings and teams: “I used to set very high standards for myself and for my team, and my natural style was all about ‘lemme tell you how to do it.’ ” Calling this a default pattern for most leaders, she talked of how she had to make the shift from someone who led from the front to someone who knew how and when to get out of others’ way. “For me,” Sally said, “it used to be about giving my team the directions and saying this is where we’ve got to go … your job is to … and I would describe what I expected from them in detail. Then we met again in a week and I would ask them to report to me what they had done.” As Sally said, “This definitely worked twenty years ago when business was not as frequently disrupted as now.”

Sally told us of the shift she had to make in the way she led, and recalled the time UBM made the decision to move from its traditional print business to digital. Looking back, Sally remarked, “It wouldn’t have worked to have taken that [top-down] approach” during that time of massive disruption in the business model. Sally talked about the way the disruption gave her the impetus to sit down with the team and start a conversation about a customer audience that was behaving very differently from the one UBM had traditionally served. “We sat down together and started mapping out the landscape, and over time questions began to emerge … How are people behaving? Why are they behaving that way? What is it that they need? What would it look like? What does the future vision look like?” It took time to reach a collective agreement, which, as Sally explained, was getting a group of diverse people to agree on what they were not going to do. Sally was guiding her team, not telling them what she wanted. She was facilitating the conversations and guiding the group to becoming a coherent whole. She was “leading from the back” rather than from the front.

Sally had a “beautiful moment” a year later when the team got together again. Sally said, her face lighting up as she recalled that moment of discovery, “I saw total alignment. We didn’t have to ask if we were on the same page … we were like a school of fish that swam together making patterns.”

When we spoke with Sally, she told us how the change in culture at UBM made Social Leadership possible. “UBM is now a business that is governed by principles rather than by rules,” she said. Speaking about the positive impact that the paradigm shift created, Sally talked of how that made it possible for leaders to adjust: “We learned how creating value is more important than capturing value … and in the end, when we have created value, we end up capturing value anyway, but that is not the purpose.” That is an apt descriptor for the Social Age: the only way we can capture value is when we don’t try to capture value, but rather work toward creating value for our networks in the community.

The Social Age is a new order brought about by the confluence of three major forces: digital technology, globalization, and changing mindsets and attitudes. Together, these forces are creating profound changes in the world and, more specifically, in the environment in which we work and lead. Julia’s story is about one of the ramifications of this Social Age. She was left facing the unplanned consequences of actions that had made perfect sense in previous years but were no longer useful in the current context. Julia needed to understand that, to lead in a rapidly changing Social Age, she had to tap into the passion that drives people in differing constituencies and harness them to a common purpose. What Julia needed to do was step into the shoes of a Social Leader, just as Sally did.

The Social Leader is a phenomenon whose time has come. We define the Social Leader as one who is able to harness the passions of networks of individuals by generating the Social Energy needed to achieve a common purpose. Let’s begin our journey into what it means to be a Social Leader by looking at some of the characteristics and challenges of the Social Age.

WHAT IS DRIVING SOCIAL LEADERSHIP?

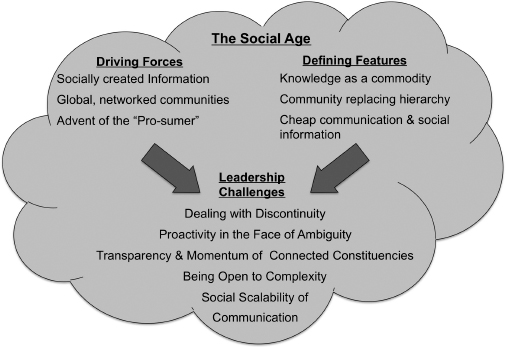

The Social Age is here. It is present and will be the context in which you lead from today onward. Let’s take a moment to step back and identify the key characteristics of this new reality.

The Social Age is characterized by:

1. Socially created information. The lines between public and private spaces are becoming increasingly blurred, leading to an overlapping social space. Information is therefore finding itself increasingly in the social space, created continually and communally and accessible to all through technology. Our organizations are becoming increasingly inhabited by individuals, and under scrutiny from stakeholders and customers, who possess three resources on a scale that is unprecedented: ubiquitous access to social information; an expectation that they can engage anyone and everyone in conversation to shape the point of view of the community; and speedy, cheap communication that allows them to react to events in real time.

2. The rise of global, networked communities. Driven by passion and purpose, groups of people from around the world are becoming linked together in communities that are dramatically transforming the way we communicate, make choices, take decisions, and engage with one another. These global communities are also sharing information and becoming points of influence in novel ways. With information fast becoming a commodity, the competitive landscape is dramatically shifting to a context in which it is the social relevance of information, rather than the information itself, that is a source of advantage. The problem with social relevance is that we are no longer in control of it; rather, socially networked communities whose actions, decisions, and interactions are beyond our jurisdiction bestow relevance upon information.

3. The birth of the prosumer, who is completely at home in the Social Age. The term prosumer defines the shift in individuals from consumers, who seek to acquire goods and services that are created for them, to contributors proactively engaged with companies and one another in the creation, development, and even the conception of the products and services they use. A mind-set of transparency, participation, and engagement have created a new generation that is starting to have an impact on the creation, dissemination, and absorption of information. As employees and as consumers, they expect to have a voice in the products and strategies of companies they care about.

As a result of these three factors, our organizations are being driven to act more like communities than like traditional hierarchies. Leaders in organizations are experiencing a shift from planning to agility; instead of generals directing their troops, they are becoming mayors managing diverse constituents. All in all, these factors have created five leadership challenges that are unique to the Social Age:

1. Dealing with discontinuity. Although business discontinuity has always been around, it occurred in rare and dramatic ways. Today, business discontinuities are the norm—from mobile apps transforming the cell phone to streaming video destroying the video rental market to data mining of search terms remaking epidemiology.

The ability to pick up “weak signals” emerging from an adjacent technological or industry space and respond to them speedily is fast becoming a leadership challenge of huge importance. When Nokia was at its pinnacle of success in the early years of this century, it failed to capitalize on a few weak signals that were happening outside its field of vision. The most critical one was Google, a search engine company, buying a small start-up in Silicon Valley called Android in 2005. As this was happening in an adjacent space, it ostensibly had nothing to do with the world of cell phones and telecommunication. But by 2008, Android had emerged as a serious contender to Nokia’s own operating system, Symbian, and Nokia’s mobile phone business entered a downward spiral from which it never recovered.

2. Moving through ambiguity. Leaders are under pressure to act in a constant state of ambiguity, and must trade predictability for confidence in their ability to be agile despite frequent disruption. For example, no longer is it possible for a leader to focus only on “her team” or “his organization.” Leaders today are expected to influence a wide range of constituencies, sometimes two or three steps removed from their “official” range of responsibility. These relationships are often devoid of authority or loyalty, making them complex to manage. The emergence of networked groups of constituents tied together by shared passion and common interests has created more complex business landscapes than ever before. Further, the need to influence multiple stakeholders who may not be in agreement with you is another major shift from the traditional model, in which old factors of loyalty and reporting lines made it easier to “manage” people.

3. Demands of connected constituencies. The socially enabled organizations in which we lead are driven by the demands for transparency from our instantly connected constituents. In fact, transparency is fast becoming the defining characteristic of the Social Age thanks to the blurring of lines between the private and public spheres. In the Social Age, it is no longer possible for a leader to have a “game face,” one that is shown to the world but is inauthentic. In fact, we are finding that the demand for authenticity has never been higher, as workplaces become increasingly flattened and transparent, and a new generation of “digital natives” and early converts to the Social Age start exercising their demands for transparency.

4. Working with social information. The speed of change and the rapid propagation of information mean that the Social Leader must be able to operate using multiple perspectives. Constituents’ expectations for multi-way communication and constant commentary result in “meaning” being created in public continually, communally, and quickly—i.e., social information. The ability to make adjustments and remain adaptive, to work with contradictions, and to do all this without compromising credibility have become essential aspects of leadership in the Social Age.

5. When everyone has a megaphone. The inhabitants of the Social Age carry megaphones and live life out loud. Speaking to the entire organization was once the purview of senior leaders. Thanks to social media—from purely social sites such as Facebook to proprietary internal social media platforms, to socially driven work platforms to external blogs devoted to a company or industry—everyone who cares about a company can speak to everyone else who cares, inside an organization or outside it. In this new reality, a leader must be able to pitch communications in a way that is appropriate for an individual, a group, and the community all at once. As importantly, a leader needs to be aware of how communication travels like a light wave, spreading across communities within a network in real time.

STAYING RELEVANT IN THE SOCIAL AGE

It was almost twenty-five years ago that John Kotter wrote the deeply influential Harvard Business Review article “What Leaders Really Do.”1 He told us that a leader’s primary role is to help people cope with change and that leaders actually do three things: they set direction, align people, and motivate and inspire others. That article set the focus of leadership for an entire generation, and corporate training departments, business schools, and individual executives all took this sound advice to heart. These efforts set in motion a school of thought that placed leaders at the pinnacle of sense making within organizations. They became accountable for creating meaning and bringing employees together in common cause. Around the same time, something else of consequence happened: the Internet came into being and forever changed the world.2

The birth of the information age and the so-called knowledge era provided us with access to huge amounts of information, and before we knew it, information was fast becoming a commodity. Information was no longer at a premium, dealing the first blow to hierarchies sustained by the notion that those at the top knew more than the rest. Soon, the information age gave way to the Social Age, a post-information age in which information—facts and data plus a point of view—is created continually, communally, and simultaneously by networks of people joined by shared passion around a topic rather than through geographical or organizational allegiance. We’ve turned from mere consumers of information into consumers and producers.

The year 2013 will be remembered for two events that marked the passing of the old world order: one, the Encyclopedia Britannica ceased publication. What was once considered the pinnacle of objective knowledge—gleaned and documented by experts—was replaced by Wikipedia, a platform on which information could be published and edited by anyone with Internet access. Two, Google celebrated its fifteenth birthday, a coming of age of the divide separating those born before Google and those who have only ever worked, learned, and communicated in a world where information is fully available and social media communication is the norm. In two swift blows, the world was transformed in ways far more impactful than those wrought by Gutenberg’s fifteenth-century invention of the printing press.

So, coming back to where we began, are you leading in a way that is relevant to the digitally connected community? The role of leadership in helping an organization cope with change and uncertainty has perhaps never been more important. The tasks of leadership that Kotter outlined—alignment, direction, and inspiration—appear as valid as ever. How a leader delivers in a hyperconnected world where employees have access not only to facts and data but to everyone’s viewpoints is what has changed dramatically. One need only look at the results of the 2013 Edelman Trust Barometer3 and note that 40 percent of people who consider themselves “informed” about a company find the statements of a CEO credible while 41 percent find what they learn through social media credible. Clearly, leaders are now competing with “the community” over who gets to make sense of what is happening in and to the organization.

But Social Leadership is not about competing with “the community” to create a galvanizing point of view. Rather, it is about how to lead in a Social Age that has been reshaped by digital media and in organizations that have become socially enabled with employees more connected than ever before.

The growth in worldwide connectivity over the last twenty-five years has been astounding. According to the Internet Systems Consortium the number of Internet hosts has grown from just over 300,000 in 1990 to well over 900 million in 2012.4 Facebook announced in its 2013 Q1 financial filings that it has 1.11 billion members. It has grown so large that, if it were a country, it would now rank third in terms of population, ready to surpass India for the number-two spot very soon. A 2012 study in the United States found that 75 percent of employees check some form of social media at work regularly5 while a study in Ireland found that the rate was 80 percent.6

Virtual communities based on personal interests spring up constantly. Digital innovations now connect us personally and in real time to events, items of personal interest, and content that sparks our passion. This digital coming together involves not just a person and information of interest to her, but a person, information of interest, and other people who find the information of interest. Today, connections have become instant, constant, and unmoored from constraints of geography or time. Talent is more mobile than ever. In such a world, the ability to harness the passions, interests, and relationships among people is fast becoming a key differentiator of successful leadership.

OUR MILITARY HERITAGE

Those of us who came of age before this new socially connected digital world are immigrants to it, and we need to learn how to succeed in this new context. From the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, the root metaphor around which organizations have traditionally been led, either consciously or inadvertently, has been military. “Marshal your troops” and “Get back to the war room” continue to be common phrases used in business; in an organization that one of us was connected to, common cautions were, “Don’t raise your head above the parapet” and “Watch out for the snipers.” We talk of “providing air cover” and “watching your back,” little realizing how deeply pervasive the military metaphor has been. The keys on our computers echo the same message: the Esc key, the Ctrl key, the Cmd key all resonate with the metaphor. So do the origins and the context of the word “strategy,” which embodies the worldview of top military brass planning an invasion, then communicating it through the ranks and finally to the troops, who then have to follow the orders. As parents of children who have grown up embracing a Social Age in which transparency and constant availability of information are taken for granted, we are concerned that the military metaphor has outlived its usefulness, even as many organizations continue to flog it.

One big reason that the military metaphor worked for organizations was that the world in which we have been operating was relatively stable and followed a linear order of causality and predictability. Leaders as “generals” led their troops to war, and that model worked as long as the enemy could be identified and strategies could be developed that relied on a predictable macro environment.

COMPLEXITY VERSUS LINEARITY

Complexity is the opposite of linearity, not the opposite of simplicity, a common misunderstanding. It happens when unforeseeable factors converge and interact in unpredictable ways to create a situation that is not only unpredictable but immune to the traditional rules of decision making. Complexity has three main characteristics: one, a complex system is self-organizing, which means that it consists of agents whose actions cannot be controlled or predicted; two, it is adaptive, which means that the diverse agents make decisions to interact with one another; and three, it is emergent, meaning that the result will always be greater than the sum of its parts. In a nutshell, complexity is the absence of the traditional data points and information that we rely upon to make decisions when leading like generals.

It shouldn’t take long to note two things: one, complexity is increasingly defining our business landscape. In a study we conducted with senior decision makers and CEOs in twenty-four different organizations, including the United Nations, spread across a number of industries, 89 percent of the over 500 interviewees agreed that complexity (defined by the pace of change and the unpredictability of the system) is their number-one challenge. Two, in a complex business landscape defined by self-organization, adaptability, and emergence, the root metaphor of leadership as a general commanding his troops is seriously limited.

So what is the alternative to the military metaphor and to the notion of the leader as general? We are convinced that the root metaphor for organizations in the Social Age has already shifted to community. Studying successful leaders tells us that the apt metaphor for the Social Leader is that of a mayor.

RETHINKING LEADERSHIP FOR THE SOCIAL AGE

A business with leaders operating as mayors, employees as members of networked communities, and teams held together by common passions and interests rather than hierarchy is not only possible but a requisite for meeting the core challenges of today’s business environment.

What does it mean to lead in this new Social Age? The topic of leadership has been explored and analyzed by psychologists, business experts and laypeople for years; some have looked for timeless principles and have made great strides in understanding the underlying aspects of successful leadership. Others have looked for specific behavior patterns and have provided prescriptive models of successful leadership actions often targeted at specific types of followers, leaders, or organizations. But nearly all those who have sought to understand leadership have agreed on one thing: leadership does not occur in a vacuum. Leadership occurs between the leader and the led within the context of the world they inhabit.7

Our own understanding of leadership proceeds from two core beliefs. First, the proper context in which to understand leadership is the moment in history in which it occurs. This transcends particular organizations, particular types of employees, and particular cultures. All of these are important, but “the times” in which the leader seeks to lead, we believe, profoundly influence what it takes to become a successful leader. For example, in Personal Growth, African Style8 one of the authors describes the challenges of leading in post-apartheid South Africa, as the African empowerment movement advances into a second generation. Much of the learning and guidance on leadership in that work is based on the deep influence of the particular moment in history in which South Africa finds itself.

In this book we seek to understand leadership in the current historical moment of the Social Age, a time when the digital world has expanded our capacity for social networking in the “real world” and has rekindled the age of operating in communities.

Our second core belief is that leadership must be understood at the level of the individual leader—who he or she actually is. This means understanding the fundamental aspects of successful leadership in this moment in history and helping individuals expand these characteristics within themselves.

In this regard, we find ourselves taking a different approach from those authors and leadership development practitioners who advocate the idea of leadership competencies. Leadership competencies are often described as patterns of behavior, and it is quite popular in leadership development practice to seek to identify a set of leadership competencies tied to a particular organization and then help leaders either acquire or improve these patterns of behavior.

Embedded in competency approaches to leadership is the assumption that the proper focus for improving an individual’s capacity to lead is based on changing or redirecting his behavior. An individual’s behavior is unquestionably a crucial component of his ability to lead. However, we think that helping a person acquire a new pattern of behavior that is inconsistent with who she is as a person is not a recipe for either long-term success or personal fulfillment. Rather, we believe that helping an individual increase her success at leading depends on helping her to better understand who she is and how she can capitalize on the most productive aspects of her own approach. Our research indicates that authenticity is crucial when operating in an interconnected world in which organizations function like communities. Therefore, helping individual leaders to grow “who they are” needs to become the primary goal of leadership development. This is in contrast to the more common approach of looking at leaders’ behavior in terms of competencies and helping them change “what they do.”

THE TENETS OF SOCIAL LEADERSHIP

While we will explore the concept of the Social Leader fully throughout the book, we start by proposing the Social Leader framework based on what we refer to as the Tenets of Social Leadership. We have developed these tenets after carefully examining the hundred-odd years of research on the topic of leadership and applying our combined experience of close to sixty years helping develop leaders.

Mindfulness: the capability to maintain and act on four types of awareness: temporal, situational, peripheral, and self

Proactivity: the belief that one is in control of one’s own actions and seeing oneself as able to influence events rather than being dragged along by them

Authenticity: engendering in others a belief in your own credibility; the ability to build personal trust in a relationship and positively confront disagreement and competing points of view Openness: the capacity to act, thrive, and learn from situations that are complex, novel, and ambiguous

Social scalability: fluidly communicating separately and jointly to: one individual, a small group, and the entire organization

We intend to look at the productive and unproductive aspects of these tenets as they relate to an individual’s success at being a Social Leader and address the five core challenges of leading in the Social Age.

Social scalability is a new concept that we believe is crucial to leading in a community-based organizational context. Social scalability is the leader’s capacity and comfort in moving between leadership situations of different scale—leading one person, a small group, or a large organization. One of the greatest changes brought on by social connectivity is the closing of the social space between leaders and followers. A leader’s success today will in large part be based on her capacity to move fluidly between leadership moments, and these moments will involve groups of different sizes—often outside the leader’s control or choosing.

IN SUMMARY

The Social Age is characterized largely by three key points: 1) socially created information, 2) the rise of globally connected communities, and 3) the birth of the prosumer who is completely at home in the Social Age. These forces have defined the Social Age as a time where knowledge is a commodity, the community is replacing the hierarchy as the basic structure of work, and cheap communication and social information impact everything.

Together, these aspects of the Social Age have created five crucial leadership challenges:

To deal with these challenges leaders need to evolve their mind-sets, approaching leadership as if they are mayors harnessing the Social Energy of diverse communities rather than generals leading troops into battle. We believe that this is best done through a focus on the five Tenets of Social Leadership:

- Mindfulness

- Proactivity

- Authenticity

- Openness

- Social Scalability