7

Moving Through Ambiguity: Proactively Influencing the World Around You

I don’t like that man. I must get to know him better.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

GENE AND MARY MEET WITH THEIR TEAMS

The RFID crisis team, as they called themselves, met six times and fleshed out a clear path forward. There would be changes to almost every part of the company and rigorous cost cutting to balance out the expense of adding the new division. Tom had insisted they all take the plan back to their respective departments to see how everyone reacted. Of course, these meetings were more like town hall meetings than briefings, as everyone seemed to have already heard about the plan and formed an opinion. Someone had even started a “Got Bulk?” thread on IKU’s internal blog.

Passions were running high across the board. When Mary e-mailed all of her senior designers to come to a meeting in Milan to discuss the plan, one responded by asking if the meeting should be in Hong Kong. Gene learned that the design engineers in Bangalore had started a job-lead sharing page on Renren, the popular Chinese social networking site.

Mary called her meeting to order and shared the outline of the plans for the new division with her senior designers. She said, “This is the best thinking we have come up with so far. Everyone involved is holding meetings like this to get a bigger perspective.” Everyone already knew most of what was said but some of the details came as a surprise. “Mary, we have been talking about this for the last month among ourselves. In our view, the approach unnecessarily limits what we can do creatively. Here are five things we’ve come up with that can give us back some creative freedom and an ability to better respond to customer requests,” said Gian Carlo, speaking for the group. “Look,” said Mary, “I believe creativity should be at the heart of everything around here. I’ll support anything that drives that home and also helps IKU succeed.”

Mary looked at the list and realized two things: they were right about the changes they suggested and, since each of these items would change aspects of the plan that affected other departments, there was no way to know what the ripple effects would be. Mary looked up from the list and said, “If we are going to create these changes in the plan there are a number of things we need to do.” She led a discussion on getting more detailed information on costs and process, and the group talked about how to connect with clients to ask for their input. Then she said, “We will need to move quickly. We can definitely influence the plan with these changes if we act now. Getting sales and industrial design on board will be critical. I can work with Tom Lee, but I don’t speak engineering—who can take that one?”

When Gene arrived at his team meeting, everyone was a little cranky. The meeting was in Bangalore, where most of the industrial designers worked, and a number of the senior R&D staff from New York had flown over. Gene had postponed the meeting three times because some emergency had come up, and now he was twenty minutes late. He walked into the conference room and said, “Sorry, I had a call with someone from auditing and he just wouldn’t let me off the phone. I’ve noticed you have all been busy chatting on this cute page on Renren, by the way. Let me lay out the plan for you.” When he finished, Gene said, “As you can see, they took our design specs as the foundation for the plan so we should all be happy. The company will do a great job putting this in place.”

Rakesh, the longest-tenured manager on the team, looked around and said, “Gene, we are all happy the company liked our ideas on the design for the new equipment. We think that the implementation could be better. We have some ideas we would like to share.” Gene raised his hand, “Rakesh, I appreciate you and everyone here. But how our ideas get implemented is not our concern. What we need to do is listen to what we are asked for and then deliver it. We’ve done that and you all have done a fine job.”

Rakesh continued, “Just a few changes, for example, in the sales data process and the way distribution centers are planned to operate might help us in the future.”

“I take your point,” said Gene, “but I cannot change the way those departments operate. We are the engineers, not the business planners. But I’ll tell you what, send me an e-mail with your notes and I will send them around to the team. But don’t get your hopes up. Now, just let me say again, good work on this, everyone.” Rakesh sat down.

THE CHALLENGE OF AMBIGUITY: PARADOX 1

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune or to take up arms against a sea of trouble …?

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

If you want to lead, Hamlet, you don’t have a choice. To be or not to be? To do or not to do? In our work, we have watched leaders struggle with this choice. And some have successfully waited on the sidelines for “strategic direction from above” and then “led their people to flawlessly execute” on the received strategy. This, of course, was General McClellan’s approach during the American Civil War. While this tactic may have worked in the past, all we can say to those who attempt this today is, good luck. In a world where leaders were crucial linchpins in a downward flow of communications and strategies were set for long periods of time, this passive approach had an opportunity to succeed.

In today’s networked world, where everyone has access to broad communication tools and can shape the conversation, standing on the sidelines is not a productive option for a leader. And yet simply defaulting to the activist general—Ulysses Grant, for example (in contrast to McClellan)—and shouting “troops, take that hill” is also a recipe for leadership failure. Aligning people with your point of view is possible but not always productive when passionate employees wish to be fully engaged in creating a communal point of view.

How does a productive mayor–leader take an active stand without alienating constituencies who expect to participate in setting direction and creating meaning? To be productive, the Social Leader must address the first paradox of succeeding within ambiguity: holding a values-driven point of view and influencing constituents to move toward this point of view while acknowledging the validity of other viewpoints. A leader does this by communicating his viewpoint as a point of view rather than the point of view.

Further, the troops no longer stand silently waiting for the general to speak. The mayor uses every moment to shape the cacophonous din of many constituents participating at once. Most importantly, the productive Social Leader believes that she is capable of influencing and harnessing these passions rather than being carried away by them. In this way, the Social Leader is an “actor in” rather than a “receiver of” socially created meaning.

To perform this balancing act, a Social Leader must be a performative artist; we will come back to this after we’ve discussed the second paradox.

THE CHALLENGE OF AMBIGUITY: PARADOX 2

David Levin, then CEO of UBM, needed to transform the company’s business model away from print publications and into events and data analysis. The first step in this transformation was, as he described it, “generating self-belief” within the organization and the leadership. He did this with start-up projects in media, events, and data management. He worked to make sure that word spread about successes. This went a long way toward helping the community of employees believe that, not only could they succeed, they could shape and drive the direction of the transition.

Not only must a Social Leader have the self-belief to act, he must be willing to act in the face of imperfect understanding and incomplete information. That you will not have all the information before you act is today a given. More to the point, it is unlikely that, with the information you have, you will be able to form a definitive prediction about the near-future environment you will face.

A recent report by Duke Corporate Education titled 2013 CEO Study: Leading in Context makes clear the challenge leaders face in taking action in today’s interconnected, socially driven landscape: “These CEOs emphasized how difficult it is to lead effectively in a context where the shelf-life of information is unstable, the interconnection of information resources is non-linear, access to information is uncontrollable, and the source of true differentiation lies in figuring things out as opposed to finding things out.”2

Rather than posing a solution to this challenge, the study’s authors pose a provocative question for a leader: “How long can you hold on to multiple conflicting hypotheses about which course of action to take until you can see the way forward that gives you the most leverage?”3

This suggests a significant revision to the old metaphor of Tarzan swinging through the jungle on a vine; traditionally, if he is to move forward, Tarzan must let go of the vine he knows is stable and grab the next vine without assurance that the new vine will hold. In today’s world, the challenge for Tarzan is to swing out on the first vine without knowing whether he will come to another vine; or if the jungle will transform into a sea instead, or into a city, and he will need to hail a cab instead of grabbing a vine. It is one thing to move from a stable vine to another vine without full assurance. It is another thing entirely to set out on a vine without being sure if your next move is to grab a vine or a boat or a cab.

How does the mayor–leader maintain the capacity for action amid an unpredictable competitive landscape? This brings us to the second of the two paradoxes: maintaining a clear sense of self-efficacy (a personal fact-based belief in your capability to succeed or, as David Levin called it, self-belief) while being willing to live with ambiguity and move without complete understanding (or knowledge) of all of the forces, stakeholders, and contingencies that can affect your success. In short, keeping your sense of self-belief without knowing all of the answers.

The ability to hold together the paradox of self-efficacy amid ambiguity creates the context for a leader to be proactive. This means asserting and maintaining influence on the direction of events with:

- Multiple constituencies expecting a voice in setting direction

- An inability to control the flow of information

- An imperfect understanding of current influences and future events

PROACTIVITY

Addressing the challenge of ambiguity is the Tenet of Social Leadership we call Proactivity, the belief that one has the ability to initiate, execute, and control one’s own actions in the world.4

In our case study of IKU Industries, Mary and Gene are bringing to their teams the plan for building a new division and transitioning the company. Immediately they are confronted with the realities of the Social Age:

- They were not in control of information—their departments were already aware of the plan, had formed an opinion, and had created responses while the leaders on the crisis team were talking among themselves

- The staff was not just talking among themselves but across the organization (and, in the case of the industrial designers, outside the company as well)

- Their people wanted very much to influence what was going on and expected to be able to do so

- Any action involved areas not within the leader’s direct control, requiring influence and the blending of additional agendas

Looking at Mary and Gene, we see two contrasting styles. Mary took on the challenge of proactivity headfirst. She demonstrated in the conversation with her team the actions she was willing to take. And she demonstrated by her behavior that she saw it as her role to continually influence both the conversation and the execution of the plan across all constituencies. Gene, by contrast, took his meeting as an opportunity to inform his troops, praise them, and tell them to wait for orders from above.

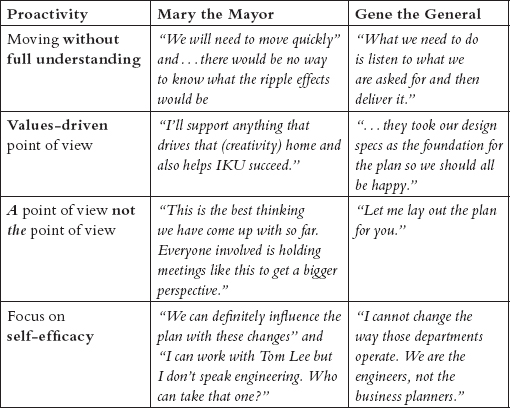

Here is what their CABs look like through the lens of proactivity:

Here we see Gene poised at the threshold of inaction. Caught up in linear logic of either/or, he has faith in the plan and in “the company” rather than in his own ability to influence events. As a leader he is working to define the space in which his department should operate and encourages his team to focus on these accountabilities, leaving everything outside the frame to others.

Mary, by contrast, has a strong sense of proactivity. Her actions and behaviors convey to her team that anything that drives their collective purpose is fair game. Notice that we said collective—not common—purpose. Mary does not seek to “align” her team to her plan. She is looking to them to shape the plan and interpret what is going on. She is clear about what she values and what she will support without insisting that others sign on to her values.

Earlier in the book we talked of Jonathan Donner, vice president of global learning and capability development at Unilever. Unilever, which began as a merger of English and Dutch companies, operated using a dual corporate structure with co-CEOs headquartered in both the Netherlands and the United Kingdom for nearly seventy years. In 2005, Unilever changed its management structure in favor of a single CEO and dramatically simplified the organization, moving to three divisions from eleven. These moves created a considerable amount of ambiguity and uncertainty throughout the organization. A critical approach to dealing with the transition was to pull the leadership around the world together to help forge the vision and direction of the renewed Unilever.

Jonathan was tasked with leveraging the fabled London-based training center known as “Four Acres” to accomplish this task. Over a five-year period Jonathan directed Four Acres to bring hundreds of senior executives from around the world together on world-class development programs with the active participation of the CEO and Board, to actively participate in the business vision, which was originally called “One Unilever” and later became “The Compass.” As these visions matured, and with the appointment of a new CEO, this community of leaders increasingly cast their ambition towards developing and emerging markets, with a focus on Asia. Given the iconic status of Four Acres and its role in shaping Unilever’s business, leadership culture, and talent, the decision was made to build a second Four Acres Leadership Centre in Singapore.

Based on a personal commitment to maintaining the concept, standards, and intent of Four Acres as it was translated to Asia and expanded globally, Jonathan requested a relocation to Singapore to complete the build process and lead the stabilization of its initial period of operation. “While we sought to build a second, magnificent Unilever learning site, I was acutely focused on creating the existing concept that respected the importance of how the content we delivered connected with the context we were creating. Creating meaningful content for participants and the business, while protecting the concept of Four Acres, I saw as critical to the Singapore center becoming a sustained success.”

Jonathan’s initial work involved directing architects and construction firms, bringing in renowned learning design experts, engaging in discussions and negotiations with government officials, and importantly, ensuring that the voices and needs of internal Unilever constituents were managed and represented. In June of 2013 the $40M-plus learning facility, recognized for its environmental design and spanning six acres, was opened by CEO Paul Polman and the Singapore Prime Minister. As we discussed this with Jonathan, he told us about the first groups he approached to attend Four Acres Programs in Singapore, which included global executives from the Americas, including Argentina.

A quick check of Google Earth will explain the confused looks we gave Jonathan. As he explained, putting a Four Acres center in Singapore would only have meaning if it served the same purpose as the center in the UK—ensuring the diversity by connecting executives around the world to join the conversation and influence the direction of the company. Putting a learning center in Singapore was a way to communicate the importance of Asia to the future of the company; having it only serve Asia while the UK center served the west would not be in line with the Four Acres mission to develop a global community of leaders. Since then, Jonathan has worked hard to defend and underline this logic in the face of travel budget cuts and continued challenges, as he sees this standard as vital to the long-term integrity of what Four Acres uniquely represents to Unilever.

We see in this example many of the same productive aspects of proactivity we saw in our fictitious leader Mary: a willingness to take action, even without a full understanding of all the contributing influences and potential outcomes, and actions based on values and a willingness to work with multiple points of view. We also see the breadth of constituencies a leader in the Social Age must address and the need to act beyond boundaries to maintain one’s influence. Let’s look at each aspect of proactivity in turn and explore the productive conversations, actions, and behaviors in which Social Leaders engage.

LEARNING TO BE A PERFORMATIVE ARTIST

We draw the term performative artist from the work of philosopher Jürgen Habermas, who coined the term performative contradiction.5 A performative contradiction is a paradox in which the content of one’s actions and the actions themselves contradict each other. For example, the statement “There is no such thing as truth” is a performative contradiction because the speaker is making a claim he believes is true but which states there is no such thing as truth. Other examples include creating a plan that encompasses the idea that it is impossible to predict the competitive landscape or asking everyone’s input on a strategy that is already fixed.

Leading in our socially defined, discontinuous world means being able to remain credible (and sane) while creating and leading within performative contradictions. For example: “We must keep everyone engaged while we reduce head count 10 percent.” How can you, the productive mayor–leader, make this statement and expect those around you to take you seriously? Answering that question takes us into the heart of performative artistry.

Values

The performative artist knows that being productive in the face of contradictions means understanding and living your values. In the example above, the Social Leader making the head count statement may have a strong belief that “making positive contributions at work is a way to maintain one’s pride” and may have communicated that this is a core value for her. If that is the case, when she announces, “We must keep everyone engaged while we reduce head count 10 percent,” what everyone hears is, “I will help you maintain your pride even if you are affected by this reduction.”

Of course, it will do you no good as a leader to suddenly “discover” your values at the moment they are needed. Try this: make a list of some of the most difficult decisions you have had to make. Recall what was behind each decision—on what did you place value? The list might seem a bit long at first. Now, for each item on the list ask yourself, “Would I walk away from my job if I were asked to violate this value?” Be honest and the list will get shorter quickly. Now you have your true core values. What do you do with them? You may want to try three things: always act with these values in mind, let others know that you are doing so, and hardest of all, remember that others hold values too, and their list may be different. This brings us to acknowledging the validity of other points of view.

Valuing Others’ Points of View

If you have spent any moment in your life reading or thinking about philosophy (including that required freshman class) you may be aware that for centuries the debate has raged over whether logic and truth exist independently or only as part of our subjective points of view. The Social Leader learning to be a performative artist will have to suspend that debate, however interesting it is, and focus on one fact: every single day, we have conversations, take actions, and behave in ways that are characteristic of ourselves. All of these CABs are drawn from the way we see the world, and our vision of the world is strongly impacted by our values.

Other people also have a vision of the world, and their vision is strongly impacted by their own values, which may well be different from yours. Keeping this in mind and holding that contradiction together is what drives success as a performative artist. How can you do this? There are three steps:

- Use CABs that clarify that you are acting from your values and that you recognize that others may have different values

- Ask those around you how they see the situation—the contradiction—and decipher the relevant values they hold

- Widen your field of vision so that your CAB takes into consideration the perspectives of your constituents

SELF-BELIEF

Recently, one of the authors of this book was working with Fabrizio Alcobe, SVP of Administration at Univision Networks. While driving to a meeting, Fabrizio explained that he was in the middle of a difficult negotiation with another senior manager. The negotiations were complex because a good many people were involved, not everyone was fully aware of all the aspects of the negotiations, and some very senior public figures were in danger of being embarrassed.

Fabrizio was concerned but confident he could handle the situation. As he explained, while working in a different company several years earlier he had learned that his boss was to be fired and that he would be involved in arranging the severance agreement with the board of directors. It was a real trial that tested his loyalty and forced him to deal with a shifting political landscape. Though the situation was personally painful, the executive learned that he was capable of identifying what information needed to be conveyed to whom and doing so with the discretion necessary to keep these sensitive activities on track while also maintaining his own sense of loyalty (a core value for him).

He carried this belief in himself, this efficacy for managing sensitive political situations, into his current role. This sense of self-efficacy allowed him to maintain an active role in these negotiations, directly and positively influencing both the specific details of the deal as well as the quality of the relationships with those involved. This self-belief was not a fanciful hope but a fact-based belief rooted in real experience. The term self-efficacy originated with one of the twentieth century’s great psychologists, Albert Bandura.6 Essentially, Bandura was referring to a person’s fact-based belief that if he tries to accomplish a particular thing he will succeed (for example, leading a group through a crisis, remaking a company’s business model, or carding par for a round of golf). Notice that we are talking about fact-based beliefs. Bandura was not suggesting a plot from a feel-good children’s movie in which a group of poor-skilled ballplayers overcome their highly proficient rivals simply because they have heart and believe they can succeed. While this may be a great story line for Disney, it’s an unproductive approach for a leader. Self-efficacy means looking at past successes and extrapolating to a current set of circumstances.

How can you develop this sense of self-efficacy? First, it is important to recognize that there is no true thing as general self-efficacy, that is, “I can achieve anything.” True self-efficacy is rooted in a particular activity, for example, managing a complex political negotiation. Then it is about creating opportunities for yourself so that you develop a track record of success in an area. These opportunities need to be scaled in a way that you can both create success and recognize the CABs that led to this success.

Let’s draw a lesson evident in the stories of both Fabrizio Alcobe and UBM’s David Levin, who worked to build self-efficacy for business transition into his leadership team. Levin purposefully set up a number of test cases and small trial projects; our TV executive was thrown into a situation where he needed to be a part of terminating his boss. Importantly, though, he was a part of this process and not the key driver, and though a misstep might have hurt his career it was unlikely he would be in a position to make a catastrophic mistake.

Both of these stories show us the same pattern: a novel situation in which the stakes are real but manageable, ultimately ending in success (even if there were some setbacks along the way).

Also, the leaders in both these situations took the time to examine the CABs that made them successful and were able in the future to identify similar situations—where the stakes were much higher—so that they were confident in their ability to take action to handle these new, higher-pressure situations. This leaves us with three steps for building self-efficacy:

- Make concerted efforts to have new experiences in which the consequences of failure are moderate enough to allow you to take action

- Pay attention to the CABs that allow you to be productive in this situation

- Extrapolate this success to other situations with similar challenges, but where the stakes are higher

THRIVING IN AMBIGUITY

A clear path in the Social Age is a rare thing. When it does appear, the clear path is often short and runs quickly into the fog of ambiguity. Leading has always been about taking risk and influencing others to take action when the results of those actions are not guaranteed. But at least you knew the odds that a given outcome would occur and how to influence those odds. The ambiguity that marks the Social Age is about a lack of certainty of the odds of an outcome occurring, or even the range of possible outcomes.

Ambiguity affects us all in two ways. First, it creates difficulty in choosing a course of action because our lack of predictive ability means we can no longer rely on the decision-making models we have used in the past. Second, the uncertainty associated with ambiguity creates a sense of unease and worry, especially when the range of possible outcomes is cloudy.7

Some of us naturally thrive in ambiguity. One such person we know is Angela Cretu, Group VP at Avon leading business in Eastern Europe. When we asked her about handling ambiguity she told us, “Once I have a stable point of reference, knowing who I am (strong identity, clear understanding of who we are as team or business, what we stand for, solid team around, etc.), I look at an ambiguous situation as a new playground with the anticipation and eagerness to get in, learn from it, and maximize the fun of playing with what I discover available.”

Those who do find uncertainty exhilarating rather than worrisome and are comfortable moving toward a goal in successive approximations, reacting quickly to real-time events rather than sticking to a course of action. How can the rest of us become more tolerant of ambiguity?

There is no easy answer to this question. In fact, those of us who find ambiguity worrisome rather than exhilarating are likely to always find it so. Being a performative artist means being able to thrive in, rather than being rendered frozen by, uncertainty. You can do this by focusing on three things:

1. Maintaining your long-range goals but vastly shortening your action horizon. That is, keep your long-term goal in mind but plan for and take only an immediate action.

2. Reassessing and readjusting. After each immediate action, reexamine what you know and then take the next step. The trick here is not to become stuck in analysis paralysis. You will never have all the information you need, you just need to be able to recognize that your next step will not be a disaster—it can be wrong as long as it is correctable. It is this sequence of short-term actions, quick reactions, and maintaining the long-term goal that characterizes those who succeed within ambiguity.

3. Accepting and managing your anxiety. If you find uncertainty worrisome rather than exhilarating, you have lots of company. Whenever any of us feels anxious, we use CABs to reduce these feelings. Pay attention to the CABs you use. It is likely that they are all effective in managing your worry. The question is whether they are effective or ineffective in productively influencing those around you. Expand the former and reduce the latter.

IN SUMMARY

The social age is an age of constant ambiguity. The ambiguity we face forces us to lead within two paradoxes:

- Having to hold values-drive points of view while acknowledging the validity of other points of view

- Having faith in our ability to influence the events around us while accepting the tremendous levels of uncertainty

These paradoxes are driven by three realities of leading in the Social Age:

- That leaders will face multiple constituencies who expect a “share of voice” in setting direction

- That leaders no longer have the ability to control the flow of information due to easy access to mass communication tools and the widespread interconnectivity of constituents

- That less than certain understanding of both current influences and the probabilities of future events is part and parcel of leading in the Social Age

The Tenet of Social Leadership that helps a leader to address these challenges is what we call Proactivity—remaining active and having faith in your ability to influence the events around you. The productive CABs that drive Proactivity fall into three areas:

- Being a Performative Artist: the ability to remain credible to yourself and others when acting within a contradiction

- Self-Belief: a personal, fact-based belief in your capacity to succeed in a given situation

- Tolerating Ambiguity: the adoption of productive CABs to manage the discomfort and stress of ambiguity including shortening your action horizon, frequent readjusting of your path forward, and being accepting of a state in which you are not able to have full knowledge before acting