3

The Leader as Mayor

Leadership should be born out of the understanding of the needs of those who would be affected by it.

MARIAN ANDERSON

In the previous chapter we talked about business as a community rather than as a bureaucracy, and we looked at UBM as an example of a company that successfully made the switch to a community. Our premise for advancing the community model is that the traditional bureaucratic model is fast becoming obsolete in the Social Age. This is an age in which information is ubiquitous, and it’s one in which there are no barriers to influencing both the creation and meaning of information, constantly and in real time.

SOCIAL ENERGY

Earlier we introduced the term “Social Energy,” a key resource in the Social Age. If intellectual capital was the resource that marked the Information Age, it is Social Energy that marks the Social Age. We came up with this term after interviewing more than five hundred people in twenty-four organizations that cut across diverse sectors and industries. We asked these people to describe the chief resources they felt were critical to succeeding in the Social Age. The characteristics that recurred most often were: passion, curiosity, engagement, connectedness, decisiveness, awareness, meaning, drive, empathy, agility, and purpose. When we looked at our results, we felt we were staring at something very important. There was a significant tilt toward words that were loaded with emotive content and social connectivity. Not that intellectual capital, know-how, knowledge, and so on were considered irrelevant; rather, it was taken for granted that these resources existed. It was as if the participants were looking at the next stage of evolution and saying that knowledge without a social and emotive component was becoming irrelevant.

One participant from Barclays Bank at a “top fifty leaders” workshop, described the resources needed as a “… kind of energy that needs to be in my company, something that holds us together in the absence of all the old hooks, and invites the customer to become part of it.” It was precisely this energy that Andrea Jung, the erstwhile CEO of Avon during its heyday, was able to generate, and every employee felt its presence.

But Social Energy is not new; leaders have created it and tapped into it for several generations. All we are saying is that it is becoming more critical than ever. One of the most celebrated examples of tapping into Social Energy is that of Nelson Mandela bringing together a deeply divided nation after the African National Congress came to power. He had the easier option to retaliate against the previous apartheid government and to seize back assets from the minority that had ruled South Africa for so long. He chose the more difficult path of reconciliation, allowing the perpetrator to seek forgiveness and be forgiven by the victim in a reconciliation court. Doing this created the possibility for black and white South Africans to generate a sense of emotional engagement within the larger context of building a nation.

Another example is the way Mandela chose powerful symbolic action to generate Social Energy at a Rugby World Cup final. The Springboks rugby team was long considered a symbol of racism and apartheid by the black majority of the newly formed republic. Once the African National Congress came to power, there were clarion calls to ban the team. Not only was Mandela against banning the team, he wore the Springbok colors to the World Cup final, striding out to the middle of the ground to meet the players. Black and white South Africans cheered together for the Springboks as they stormed to victory, and a simple symbolic action became the harbinger of a Social Energy that swept across the new country, touching each and every citizen.

In chapter 8 we will discuss the challenge of relating authentically to deeply connected constituencies and will explore the conversations, actions, and behaviors a leader needs to exhibit to generate an upward, positive cycle of Social Energy. For now, as we introduce the full score of Social Leadership, let’s begin by examining the underlying principles of shifting your leadership approach to be more like a mayor’s and less like a general’s.

THE SOCIAL LEADER’S FIELD OF ACTION

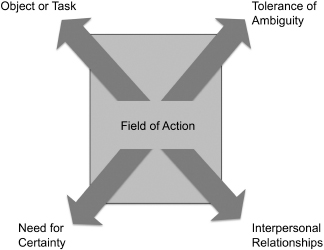

What Nelson Mandela was doing in bringing South Africa together was balancing two powerful sets of forces that impact all of us: one, the need for certainty versus the need to tolerate ambiguity; and two, focusing on people versus focusing on tasks. Take a small rubber band. Imagine that the space within this rubber band represents all of the room in which you have to maneuver as a leader. Now take your thumb and index finger and stretch the rubber band. It has gotten longer but narrower. You may have improved your room to maneuver in some ways but limited it in others. Now take your other thumb and index finger, insert them crosswise into the stretched rubber band, and spread them as well. You now have a broad square, a much larger field of action. Perhaps it looks something like this:

FIGURE 3-1 Field of Action

Balancing the dynamic tensions within these four poles—ambiguity, certainty, people, and tasks—creates a broad field of action. John D. Ingalls was among the first to describe this set of forces. He described them as follows:1

Need for certainty:

- The search for cognitive balance or consistency (logic)

- The tendency for social evaluation and comparison (judgment)

- Attribution and the assignment of motives (assumption)

Tolerance of ambiguity:

- The capacity for remaining open to experience (acceptance)

- The ability to be descriptive (nonjudgmental assessment)

- The willingness to question and inquire (experiment and exploration)

Focus on tasks:

- Positioning one’s role through the objective lens of task

Focus on people:

- Positioning one’s role through the subjective lens of relationship

Our goal as Social Leaders is to focus on all four poles, so that we live within this dynamic tension to create the most space to lead and bring constituencies together.

Ingalls describes how, for too long, leaders have focused on only half of this field of action, concerned with driving tasks and building certainty; we would call this operating as generals. As we have discussed, in today’s reality this is a fool’s errand. As a leader you must balance all of these forces and, like a mayor, pay attention to people as well as tasks and accept ambiguity while searching for some solid ground of certainty. The psychologist Carl Jung called the capacity to create this balance the transcendent function of consciousness.2 We call it being a Social Leader. Jung encouraged people to seek this balance by understanding how they perceive the world. We add that it is crucial to also understand how you act upon the world to influence those around you.

THE LEADER AS MAYOR

If, in a traditional organization, the successful leader was a general, focusing on certainty and task, then in the community-based organizations of the Social Age the successful leader will be a mayor, focusing on all four poles of the field of action—certainty, ambiguity, tasks, and people. The differences between generals and mayors are immediately obvious:

- Generals have troops; mayors have constituents

- Generals are known by their troops; mayors know their constituents

- Generals command; mayors influence

Generals lead by command based on their position in the hierarchy, which they achieved independent of the wishes of their troops; mayors govern from their position in the community, which they achieve with the consent of their constituents.

Constituents versus troops, knowing versus being known, governing versus commanding, consent-based influence versus positional authority: these are the new realities of leading within a community-based business. But how do leaders succeed within these new realities? The traditional answer to this question has been to focus on establishing correct patterns of behavior—competency models, if you will—that instruct the leader how to act and provide the organization with standards for assessing leadership. We find this approach to be challenged in several areas because it relies on leaders adopting ways of behaving that may not resonate with who they are authentically and that artificially constrict what a leader can do to be effective.

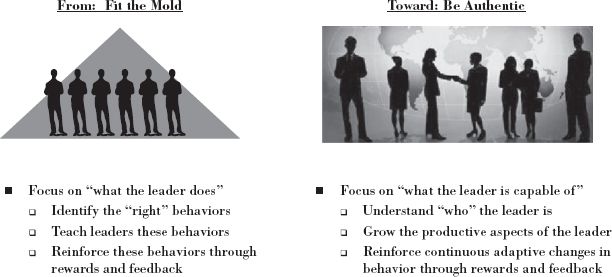

FIGURE 3-2 Generals vs. Mayors

We believe that the answer is not a set pattern of behavior or a rigid “competency model.” Creating a fixed list of successful leadership behaviors runs the risk of being quickly out of date, ineffectively simplistic or bewilderingly lengthy.

The United Nations, for instance, has a complete set of forty-three “core competencies” plus another forty managerial competencies that provide a rich and bewildering smorgasbord of all the wonderful behaviors the organization wants to track, monitor, and measure in its people and managers. An entire machinery remains in operation at the UN to sustain the production, upkeep, and implementation of this competency framework. The outcome of this mammoth endeavor to reduce human development into a neat set of measurable parameters remains dubious.

FIGURE 3-3 Fitting the Mold vs. Being Authentic

It is a fine idea to have a list of values that all employees should aspire toward. However, our experience tells us that while competency models look great on paper, a far more effective approach is to encourage leaders to become the most productive version of the person they are meant to be. Or to use the famous words of psychologist Abraham Maslow, “A musician must make music, an artist must paint, a poet must write; if he is to be ultimately at peace with himself, what a man can be, he must be.”

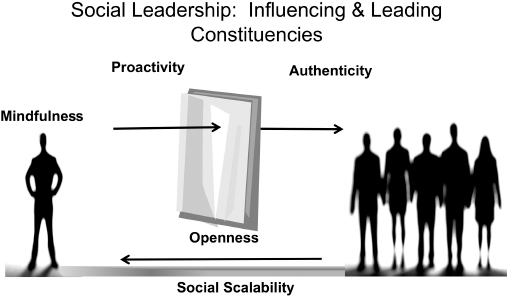

TENETS OF SOCIAL LEADERSHIP

We do, however, need a framework as the basis for a common understanding of how each of us can develop as a Social Leader. The framework must include all four poles suggested by Ingalls in his field of action. We propose that as an alternative to competency models we instead look at a framework that describes “who the leader is.” This allows each one of us the flexibility of using behaviors (and conversations and actions) that are uniquely productive for us while allowing a common basis for describing the areas of focus for success. We call this framework the Tenets of Social Leadership and suggest that there are five core Tenets. Success as a leader is based on understanding these five core tenets with regard to oneself, and learning to capitalize on one’s own most productive aspects within these five tenets.

The five tenets for becoming a successful Social Leader that we want to focus on are:

Mindfulness: maintaining and acting on four types of awareness: Temporal awareness, Situational awareness, Peripheral awareness, and Self-awareness.

Proactivity: the belief that one is in control of one’s own actions and seeing oneself as being able to influence events rather than being dragged along by them

Authenticity: engendering in others a belief in your own credibility; the ability to build personal trust in a relationship and positively confront disagreement and competing points of view

Openness to learning, growth, and ambiguity: the capacities to act, thrive, and learn from situations that are complex, novel, and ambiguous

Social scalability: fluidly communicating separately and jointly to: one individual, a small group, the entire organization

These five Tenets of Social Leadership interact in a dynamic way to form an individual leader’s Personal Narrative. A Personal Narrative is the thematic story describing an individual that 1) the individual believes about himself and 2) that others believe about that person. Others experience our Personal Narrative through our conversations, actions, and behaviors (CABs). In the following chapters we will explore the concept of conversations, actions, and behaviors as leadership in action based on the underlying Tenets of Social Leadership. For now, let’s explore the basis of Social Leadership and what this means for your own Personal Narrative.

FIGURE 3-4 Social Leader Tenets

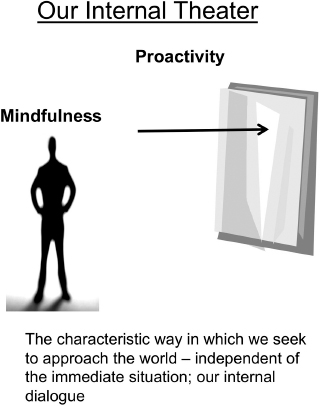

OUR INTERNAL THEATER

We use the idea of an “internal theater” to denote aspects of you as leader that are within yourself. Mindfulness and proactivity help the leader remain purposeful and aware of the conversations, actions, and behaviors she uses in leading others. Both these tenets share the characteristic that they are fully within the leader—they are part of one’s own internal theater. In large part, though not exclusively, they help determine that part of the leader’s Personal Narrative that he tells about himself.

FIGURE 3-5 Internal Theater

Mindfulness

Mindfulness allows a leader to purposely set his course of action, recognize his actions’ impact on others, and adjust them accordingly. We think of mindfulness as having four aspects:

- Self-awareness—knowing your strengths and weaknesses and being able to see the impact of your behavior on others

- Situational awareness—reading the situation accurately and synchronizing one’s conversations, actions, and behaviors to the needs of the moment

- Peripheral awareness—being able to “keep an eye” on the horizon and detect weak signals, early warning signs of trends that will have an impact over time even if they do not at the moment

- Temporal awareness—staying in the moment and recognizing when your reactions are driven from past events rather than present events

Proactivity

Proactivity concerns a leader’s ability to see herself as the initiator of events rather than the responder. To some extent this tenet has to do with the way a leader sees herself as capable and potent to influence a situation or challenge. To a greater extent, though, it is about the way a leader perceives situations and challenges—does she see them as a field on which to exert her capabilities or as an interconnected set of events to which she is a spectator. As Fred Kofman, author of Conscious Business puts it, does the leader see himself as a player or a victim?3

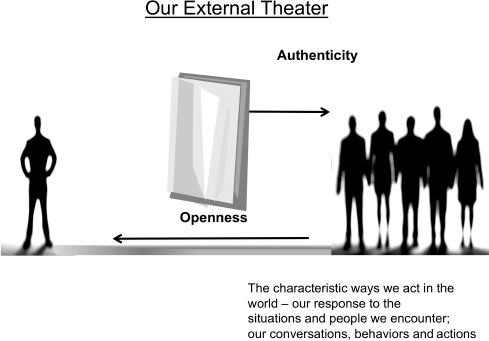

OUR EXTERNAL THEATER

We use the idea of “external theater” to denote those aspects of your leadership that involve engaging with others. Authenticity and openness focus on the ways that we initiate and respond to the people we choose to influence and lead.

Authenticity and Openness

Authenticity and openness are aspects of the leader that involve engagement with others. These two tenets in large part, though again not exclusively, determine the part of the leader’s Personal Narrative to which others have access.

Authenticity refers to the quality of relationship that the leader is able to engender with her constituents. It is built on a leader’s capacity to create an atmosphere of trust through consistent, unbiased action and to display empathy without being seen as basing decisions on sympathy. Let’s look at an example of building trust and credibility by comparing two leaders, C-suite executives with whom one of the authors has worked: Leader A has been able to demonstrate the productive aspects of authenticity and Leader B has not. When something important goes wrong and needs to be brought to the leader’s attention, the constituents of Leader A respond by saying, “Let’s go tell Leader A.” Conversely, the constituents of Leader B respond by asking, “How should we tell Leader B?” Leader A consistently learned of problems quickly and fully, while Leader B learned of problems more slowly and with “spin” that forced him to work much harder to gain a full and accurate appreciation for what was going on. Over time this had a significant impact on the success of Leader B.

FIGURE 3-6 External Theater

Openness to Learning, Growth, and Ambiguity

Just as leaders’ actions affect those around them, they are in turn subject to the actions of their constituents. The tenet of openness to learning, growth, and ambiguity refers to the aspect of the leader that allows him to experience information, experiences, and situations as new, with a positive, embracing attitude.

Psychologists have pointed out that we all look at the world seeking familiar patterns to help us quickly sort through the vast amount of information that bombards us. Once we recognize an event as essentially similar to a past experience, we know how to deal with it with a minimum of thought.4 We each have our own awareness point—that point where we see something as different enough from our past experience to recognize it as new. The positive aspects of openness are those that allow us to have an appropriately set awareness point—one that is low enough to make us appreciate the novelty around us without becoming overwhelmed. Of course, seeing something as new is only one half of the equation. The other half is embracing the novel experience and seeking to use it as an opportunity to learn and grow.

OUR STAGE

Our internal and external theater performances play out on a stage. Our stage operates like our own personal YouTube channel where the world can tune in as it chooses. As leaders we must be prepared to speak to any range of audience at any moment, and to speak while they are speaking to each other. We call this capability Social Scalability.

FIGURE 3-7 Stage

Social Scalability

The final tenet of Social Leadership, social scalability, refers to the stage on which the leader is working and his ability to transition easily from one stage to the next. In the Social Age, “who” the leader is dealing with is not always within her control. At the same time, the expectation that the leader will be available to a widespread constituency is higher than ever. In this context, a leader will need to display the other tenets—mindfulness, authenticity, personal agency, and openness—and make smooth and easy transitions among audiences, from one person to a team and the entire community.

Think of those leaders you’ve met who have this ability to influence people across the organizational spectrum, from those on the shop floor to those in the boardroom. What exactly do they do differently? Their message and the core story remain the same, what varies is their ability to connect with different people differently. Leaders who do that are able to fine-tune their message to reach different audiences. This demands a high level of empathy on their part. They work to recognize that the underlying experiences that shaped the way they see the world may be different from the experiences of those hearing their message.

Mayor–leaders also recognize that in the Social Age everyone they speak with has a megaphone. Their audience is able to—and even expects to—share not only the leader’s message but their own view point on it. And these multiple viewpoints spread virally. Transparency and communal conversation are the new normal.

YOUR PERSONAL NARRATIVE

These five leadership tenets are the building blocks of an individual’s Personal Narrative. Successful leaders have Personal Narratives that are aligned and that have productive themes. By aligned we mean that the way the individual sees himself is the way others see him. The stories that the leader tells about her leadership experiences are thematically similar to those that are told by her constituents.

By productive we refer to the character of the conversations, actions, and behaviors (CABs) the leader displays within each of the five tenets. Each of the tenets can have productive and unproductive aspects, and a leader will at times display productive or unproductive aspects of each tenet. The goal of a successful leader is to understand which aspects of each tenet are most consistently characteristic of him and then to work on capitalizing on the productive aspects and developing strategies for compensating for the unproductive aspects.

In part 2 we will dive deeply into each tenet and explore how you can use it to productively address the challenges of the Social Age as well as learn to recognize and expand your own productive capabilities in each. For now, if you want to quickly gain a deeper feel for each of the tenets, have a look at the appendix, which provides a sample list of characteristically productive and unproductive CABs for each of the five Tenets of Social Leadership.

IN SUMMARY

So far we have demonstrated seven crucial points.

1. We are living in a Social Age, a time defined by digital technology, globalization, and an expectation of participation by everyone who cares about a topic. Most of us are immigrants to this world, and bring with us a mind-set of leadership and organizations developed before the dawn of global digital social connectivity.

2. In this Social Age we see: the socialization of information, with points of view created continually, communally, and in real time; the rise of global, networked communities linked through technology and now operating as a fundamental unit of analysis to be addressed; and the rise of the prosumer, individuals and communities both inside and outside of companies that expect to have a voice in the company’s strategy and actions.

3. The Social Age is creating a number of leadership challenges, some of which are new and all of which are new in their intensity:

- Anticipating discontinuity

- Remaining proactive in the face of ambiguity

- The demands of connected constituents

- Dealing with social information

- Communicating when everyone has a megaphone

4. These features and challenges of the Social Age are pushing organizations to operate more like communities and less like traditional hierarchies. This is causing a rethinking of some of the fundamental principles upon which companies operate, including how they think of members (employees), affinity (participation and engagement), and connectivity (relationships beyond the company).

5. Importantly, the shift to community-based organizational structures embedded in the Social Age means a shift in thinking about leadership. Leaders can no longer be generals commanding troops and setting strategy; instead, they must be mayors, influencing constituencies and reacting to unforeseen events.

6. In this new reality of the mayor–leader it is important to focus on the productive capabilities of the individual leader, her Personal Narrative, rather than on a fixed set of behaviors.

7. A leader’s Personal Narrative is best understood through the lens of the Tenets of Social Leadership:

- Mindfulness

- Proactivity

- Authenticity

- Openness

- Social scalability

Now let’s look at you in terms of the Tenets of Social Leadership and see what you can do to expand your own productive conversations, actions, and behaviors in each of these areas.