9

Working with Social Information: Remaining Open and Adjusting Your Perspective

We cannot solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.

ALBERT EINSTEIN

LISA AND GENE MEET WITH HOSUR’S TOWN COUNCIL

It was a surprise to everyone when the bulk label RFID team’s plan called for the new division to be placed in Hosur, a small town outside Bangalore, rather than in Hong Kong. But the need for IT resources outweighed the manufacturing cost savings in China. It was an even bigger surprise when Bangalore politicians seemed less than enthusiastic about welcoming the IKU expansion. Construction permits and other approvals were all being held up. IKU’s legal department was making no headway in managing the infamous Indian bureaucracy. Lisa, IKU’s purchasing VP, and Gene, VP of industrial design, got on a plane to India to meet with local officials.

“Look at this,” said Gene. Before takeoff, Gene had downloaded some interesting information. The local paper had published an editorial saying that IKU’s expansion was coming at the expense of people in three slums, who were being rushed into new, unfinished government housing. An environmental group had started a blog detailing how the IKU expansion would add to local industrial waste, and a local IT professional group’s website had more than two hundred comments on a thread about IKU importing staff from China rather than hiring locally.

Gene and Lisa arrived at the Bangalore town hall expecting to meet with the town council. Instead, they found themselves confronted with hundreds of angry people. It seems someone had posted the meeting on the Internet and it took no time for lots of passionate people to mobilize themselves. Rather than participating in a reasoned discussion, they found themselves listening to speeches from local politicians playing to the crowd.

Lisa leaned over to Gene and said, “This will all blow over. Let’s just let this go on and then we can meet quietly with the town council and show them the proposal to provide some community support and donations. They’ll agree and things will be fine.”

“I’m not sure,” Gene whispered back. “I am not even sure the town council is the only decision maker. Certainly it is not the only one influencing the conversation.”

“What are you suggesting? We engage all of these people? I don’t even know how to do that. I am not even sure they know what they want. Let’s stick to the plan,” Lisa said with conviction.

“Obviously, this is a mess,” Gene replied. “No, I don’t think we should engage at this minute. Let’s talk to the town council members after this breaks up. I think we need to stay high level and not expect much. Then we need to figure out how to talk to these different groups to see what they really want and how we can help them or at least manage expectations. We are not going to walk out of here today with what we want.”

Just then their conversation was interrupted by one of the speakers from the floor, who said, “The IKU people are here, what do they have to say?” Lisa grabbed the notes she intended for her talk with the town council members and started to stand. Gene put his hand on her shoulder, stopping her. He rose instead and said, “Hello, I am Gene Koss, we’re here to listen.”

Were Lisa and Gene ambushed? No. Were they caught unaware? Absolutely. Why? It’s unlikely they could have predicted when they boarded the plane that the local council meeting they were headed for would turn into a multi-constituent free-for-all. However, they believed they were going to solve a straightforward issue, what we would call a “linear” problem. They had a construction plan and they needed permits; the town issued the permits, and the town council would want some positive community contributions to grease the wheels. Difficult negotiations were ahead of them, maybe, but it was a problem they could frame and address with a straightforward strategy.

What they found instead was not a linear problem but a complex one, a challenge with multiple independent influences creating an emergent situation that was largely unpredictable. Let’s explore the nature of complex problems and then look at the Social Leadership tenet of openness, which is the mind-set necessary for addressing complex problems.

Most business processes and most approaches to leadership developed before the Social Age focused on reducing ambiguity and creating predictability and certainty. That was a critical and meaningful activity when businesses faced linear problems. Linear problems occur when the challenges facing a company are known and operate independently. For example, events such as the increasing cost of a critical product component or the appearance of a new competitor are independent events, and models can be built to predict the impact on sales of price changes and market share changes.

Complexity—one of the hallmarks of the Social Age—is the opposite of linearity; it occurs when multiple causes converge to produce effects that are unforecastable. The word itself comes from the Latin complexus, which means “entwined together.” A complex system is composed of interconnected parts, and it exhibits properties that are not obvious from the individual parts. Complexity occurs when unforeseeable factors converge to create a situation that is not only unpredictable but also immune to the traditional rules of decision making because it is impossible to assign probabilities to different outcomes. As we noted previously, leading within complex systems tests our tolerance for ambiguity.

Complexity has three main characteristics: one, a complex system is self-organizing, which means it consists of agents whose actions cannot be controlled or predicted. Two, it is adaptive, which means that the diverse agents make independent decisions to interact with one another. And three, it is emergent in that the result will always be different from the sum of its parts. The outcome “emerges” as the situation evolves. In a nutshell, complexity is the absence of the data points and information that we traditionally rely upon to make decisions.

All of these elements were present in the situation in which Gene and Lisa found themselves. The town council, environmentalists, and local IT workers are all independent actors, and their concerns interact with one another to create additional complexity. Moreover, as these interactions occur, a spiral of downward Social Energy is generated, creating a movement away from the direction that Lisa and Gene are promoting. Further, as Gene pointed out on the plane ride, there were signals, disparate and dispersed though they were, that they were heading toward an unplanned, ambiguous situation.

In the past, the need for certainty has driven the way we behave in organizations, the way we make decisions, the way we communicate, and the way we develop our leaders. Although we have known for millennia that ambiguity is part and parcel of life and is an important ingredient in our creative impulses, our emphasis on measurability and predictability has rendered ambiguity undesirable. Curiously, an inability to tolerate ambiguity is returning in the Social Age as one of the main factors of business and leadership failure. Let’s take a look at the impact that complex problems and dealing with ambiguity can have.

THE CURIOUS TALE OF NOKIA

Nokia was the world leader in the telecom industry in the early 2000s, and was among the most profitable companies in the world. With a ringtone that had reached iconic status, powerful brand positioning, and Keanu Reeves flipping open its phone in The Matrix, the company seemed destined for success. It also had an enviable track record of reinventing itself, transforming from a lumber business to a leader in the mobile phone business.

In 2013, Microsoft bought out an ailing Nokia mobile phone division that was unable to compete with Apple and Samsung. Nokia had a 34 percent market share in 2005 and as late as 2012, it still had an 18 percent market share. At the time Nokia sold its mobile phone division, it held a mere 3.2 percent share in smartphones. What went wrong?

What went wrong with Nokia is precisely what had led Nokia to its success: expertise in the cell phone manufacturing business. Over time, this became an orthodoxy—a fixed mind-set—that began shaping the decisions and judgment calls made by its leaders. Nokia’s orthodoxy prevented its leaders from reacting to the radical disruption initiated by Apple and Google, which altered the core of the cell phone industry. iOS and Android operating systems transformed the cell phone from a phone to a crucial technological gadget at the heart of a community comprising stakeholders, such as app developers and prosumers, who are actively engaged in providing feedback and influencing the direction of smartphone development.

Nokia became increasingly isolated from consumers, who wanted to influence the user experience, not the hardware, and from developers, who wanted an easy platform to work with and a market to sell their apps. Despite having the patent for “touch”—the swipe function that all smartphones feature today—Nokia was hustled out of the smartphone market.

Nokia’s problem began with a rather inconspicuous development in 2005, when Google acquired a little-known start-up company called Android. This was a classic weak signal. It happened in what Nokia saw as an adjacent industry, and thus was easy to ignore. Our interviews with several Nokia leaders, past and present, indicate that while the weak signal was picked up in some quarters, it was not seen as critical.

At the time of Android’s acquisition, Nokia’s mobile phone business was highly successful, and there was more than a fair amount of hubris in its internal culture. The dominant position of its Symbian operating system seemed unassailable. And in a linear world, where phones remained primarily voice communications devices, it was. But by 2010 the weak signal had become a major disruptive force. The success of Google’s Android OS and Apple’s iOS as platforms for apps vastly changed the nature of mobile phone use and led to a shift away from hardware manufacture—Nokia’s home ground—toward user experience. The communities that grew up around the App Store and Google Play ecosystems changed everything.

Nokia’s own operating system, Symbian, was falling short of what the developers in the newly emergent community wanted. They found it clunky and difficult to work with, and began focusing on Apple and Android. With the threat now clearly visible, Nokia reacted to the complexity by going back to what it knew best: manufacturing quality cell phones.

What Nokia leaders really needed to do was pay attention to the information that was coming in, first from the periphery and later from all over, and adjust their perspective. Agility rather than expertise was the need of the hour. Weighed down with hubris and the burden of past success, Nokia was not able to move quickly enough to abandon old positions and adapt to the changing world. It needed leaders to step back from the situation and ask fundamentally challenging questions that dealt with the social relevance of Nokia to the community of customers and developers. Instead, the questions stayed focused on functionality, technical improvements, and manufacturing.

ADJUSTING YOUR PERSPECTIVE

Nokia was the victim of a fast-moving disruption that appeared suddenly out of an adjacent space. This is something that happens every day in the Social Age: socially created information; the advent of global, networked communities; and the prosumers who participated and championed the evolution of the smartphone all created complexity—interwoven forces that defy predictability. Nokia’s lack of agility and its inability to shift perspectives cost it dearly.

The ability to pick up information that may not be in your direct line of sight (part of your strategic direction) and to adjust your perspective quickly is crucial for leaders in the Social Age. Complex problems, by their very nature, challenge a leader’s point of view and the strategy she is executing. In the case of Nokia, the more complex the challenge became, the more the leaders insisted on returning to strategy as the element to fix. Instead, a successful Social Leader accepts ambiguity and works to gather information and build new perspectives—new points of view—rather than make old ones fit. Let’s look at an entirely different situation to uncover how Social Leaders go about taking in new information and adjusting their perspective.

LESSONS FROM A PRO

On January 15, 2009, at 3:24 p.m., US Airways 1549 took off from LaGuardia Airport for a routine flight to Charlotte, North Carolina. Ninety seconds later it was hit by a flock of geese. The pilot, Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, a veteran of forty-three years of flying, would later describe the sound of geese hitting the plane as louder than the worst thunderstorm he had heard growing up in Texas. With both engines down, the aircraft stopped climbing and lost all forward momentum. With a full tank of fuel and 150 passengers on board, the Airbus A320 was headed for disaster.

Captain Sullenberger’s immediate reaction on taking control of the stricken aircraft was to radio air traffic control and announce that he was turning back to LaGuardia. This was an immediate, default reaction when dealing with a problem at this point in the flight, part of the established strategy. Of course, having the plane’s engines shut down by geese was not a predictable event. The captain was cleared right away for the return to LaGuardia. Although managing the aircraft according to “the plan” in the midst of this unforeseen emergency could easily have occupied all his energies, Sullenberger continued to seek new information. He was willing to see information that contradicted his plan and quickly deduced that he might not make it back to the runway at LaGuardia. Seconds later he checked with the control tower to see if there was any other airport available in New Jersey and asked about Teterboro Airport.

He was cleared for that too, but he decided not to turn toward Teterboro either. Sullenberger began with the default strategy, realized this would not work, and announced his strategy—Teterboro. Under extreme stress, instead of trying to make his plan work when incoming information suggested it would not, he developed a third alternative.

Think back to a time when you stood up and announced a departure from the routine approach. It’s likely you felt good about recognizing that the standard strategy would not work. As new information showed that your revised plan was not working, did you accept this and rethink it or did you recommit to your revised strategy, making minor adjustments to try to make this plan succeed?

Back to flight 1549 …

After a protracted silence in the cockpit, which cabin attendants would later describe as resembling the quiet of a library, the captain calmly told the control tower that he was “going in the Hudson.” For the second time in the three minutes in air, Sullenberger had challenged his own assumptions based on the information he was picking up, and had readjusted his perspective.

Sullenberger’s decision to go into the Hudson was not a knee-jerk reaction to ditching the plane, but rather reveals his ability to function in a state of ambiguity. He chose that portion of the river for the landing because he had seen boats in the area that could assist in the rescue. At the time of takeoff, those boats were peripheral information, drawn from an adjacent area (the river), rather than his immediate focus (the airspace).

The lesson of this story is about not succumbing to the familiar and instead being able to operate in a state of ambiguity in the absence of known landmarks and cues. If one can do that, then ambiguity provides a medium for exploring alternatives that were earlier hidden by the lens of the familiar.

We see this contrast between the stories of Nokia and Sullenberger in the different reactions of and approaches that Gene and Lisa from IKU took at the town hall meeting. Lisa looked at the mess of competing viewpoints and constituencies in front of her and suggested that they forge ahead with the plan. Gene, by contrast, looked at the same situation and realized things had changed. The people they thought could make decisions and control the situation—the town council—were neither in control nor were they the sole decision makers. Gene realized that not only did they not have all the relevant information, they might not even have the right questions. He adjusted quickly and spun their approach by 180 degrees. Rather than viewing the meeting as a chance to make an offer and negotiate, he took it as an opportunity to listen and build relationships.

MAKING AMBIGUITY DESIRABLE

Being comfortable with ambiguity and even thriving in it is fast becoming an important leadership capacity in the Social Age. Those who flourish in ambiguity are able to suspend judgment, stay curious, and experiment with potential solutions rather than wait for the one answer. How can you develop not only a tolerance for ambiguity but also the capability to thrive in it? A recent series of studies by Michael S. Lane and Karin Klenke provides some clues.1 Based on their research, Lane and Klenke suggest four keys to developing tolerance for ambiguity: mindfulness, creativity, aesthetic judgment, and spirituality.

We have discussed mindfulness already, and its role in handling ambiguity is clear. Ambiguous situations tend to push our brains to default to familiar patterns, and therefore a leader with low awareness is bound to use CABs based upon established patterns. What about the other three? What have creativity, aesthetic judgment, and spirituality to do with being better able to deal with ambiguity?

While there are many definitions of creativity, one that resonates was shared in a discussion with us by Ian Florance, a poet and organizational performance expert who is also an associate at the Psychometrics Centre at Cambridge University: [creativity is] “seeing connections between things, and making these connections frequently.” That means being receptive to numerous and multiple inputs without squashing contrarian contributions with one’s beliefs. Research suggests that the habit of finding “uncommon connections” can be greatly increased by spending time in the pursuit of hobbies and other avocations. This is where the concept of aesthetic judgment comes into play—having a number of different ways of looking at the world and perceiving beauty.

For a business leader whose time is spent in numbers, data, spreadsheets, PowerPoint decks, and endless strategic meetings, the need for a counterbalance that produces dissonance in the brain becomes very important. In fact, a piece of groundbreaking research by J. Rogers Hollingsworth studying 450 scientists identified the role that an “avocation” plays in the development of scientific discovery.2 Interestingly, the avocations scientists in the study pursued bore no immediate resemblance to their scientific work; instead, the hobbies reported were all in the arts and the humanities. Like Einstein turning to music after he had spent much time pondering an equation, the arts “stimulate the senses of hearing, seeing, smelling—enhancing the capacity to know and feel things in a multi-model synthetic way.”3

In the context of leadership, introducing spirituality may seem misplaced, but we are thinking about spirituality from the perspective of having purpose. We have already discussed the importance of purpose as a factor in generating Social Energy. In order to generate purpose in others, the Social Leader must feel a deep sense of purpose within himself. Career analyst and author Daniel Pink’s definition of purpose is apt: “the yearning to do what we do in the service of something larger than ourselves.”4 That might take the form of finding a new way to delight a customer, solving a problem that has not yet been solved, or doing work for the joy and fun of it. Purpose is about why we do things, not how we do things.

So are we saying that business leaders need to develop artistic appreciation, focus on creativity, and have a sense of purpose? In a word, yes, but not because these three are valuable in and of themselves (which, of course, they are). The point is, to succeed as a Social Leader you will need to perceive situations from multiple and often contradictory perspectives. Aesthetic appreciation, creativity, and purpose push a leader’s mind-set toward comfort with cognitive complexity.

COGNITIVE COMPLEXITY

Cognitive complexity is a psychological characteristic that describes a leader’s skill at framing and perceiving situations in multiple ways. Leaders with high cognitive complexity process information differently because they use more constructs, categories, and dimensions to perceive relationships between bits of information. Leaders with high cognitive complexity use this capability to see relationships across many points and build relationships and influence people through networks.

What are the factors that influence cognitive complexity? Cognitive complexity is created when dissonant factors are brought together; think of a finance executive taking an art history class.5 Cognitive complexity is a state we can develop by going beyond our natural tendency to seek uniformity and easy answers. In Hollingsworth’s study of scientists, which we referred to in the previous section, he identified “internalizing multiple cultures” as a key factor that impacts a person’s ability to be cognitively complex.

DEVELOPING YOUR COGNITIVE COMPLEXITY

Were the Nokia leaders not cognitively complex? It is impossible to make that assertion, as a business failure involves many factors. However, after discussing the topic with many Nokia leaders, we believe it would be correct to assert that a culture had come to prevail at Nokia where “object-centered” rather than “person-centered” processes and communication had become de facto. One Nokia manager who left the company in 2013 after the sell-off to Microsoft said, “We had become obsessed with a process-centered world in which there was a process for every process … we had stopped talking about why we existed, what drove us to be Nokia … it had turned into a machine.” Hard words, and perhaps overdramatized, but the essence is apparent. Cognitively complex leaders tend to use more person-centered communication and are able to frame their messages in a way that helps others connect the messages to their own sense of purpose.

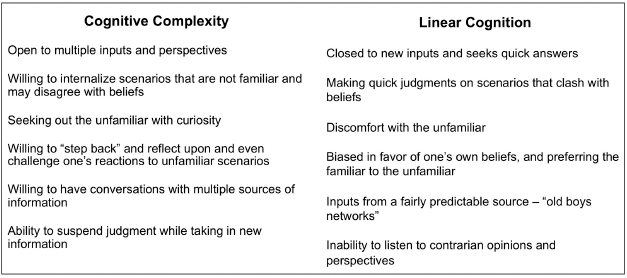

FIGURE 9-1 Cognitive Complexity

Let’s look at the factors that mark cognitive complexity in contrast with its opposite, which we term linear cognition.

One of the authors has spent a number of years teaching leadership programs that focus in part on building cognitive complexity. One such program, delivered through Duke Corporate Education, involves creating “immersion scenarios” in which senior leaders are pushed into the deep end of an uncomfortable experience. An example of this is an exercise called Dangerous Opportunities, which uses professional actors to push leaders into a place of discomfort and ambiguity.

Once, while working with a leading pharmaceutical company, we enacted a lawsuit involving an irate customer whose partner had died on the operating table, lawyers representing both sides, and the media. When company executives were immersed in this threatening environment, their default behaviors kicked in and their tendency to use linear cognition became apparent; they got stuck in the “how” rather than climbing up to “why.” Our experience with these programs highlights some CABs that can help expand your cognitive complexity, and which you might consider for your own repertoire.

10 Tips for Building Cognitive Complexity

- Become aware of your cognitive frames and challenge them

- Expand the circle of your stimuli and inputs

- Learn something new every day

- Create projects pushing you out of the zone of the familiar

- Expand your reading repertoire

- Go back to your avocation

- Travel and immerse yourself in new cultures

- Seek out new eyes through which to see the world

- Craft the story of your “why”

- Become multidimensional in decision making

OPENNESS TO LEARNING: THE “GROWTH MIND-SET”

The tips in the list just presented are all about developing a growth mind-set. Think of the leaders you’ve known: how many of them were willing to challenge their own beliefs, take in new information, and adjust their perspectives? How many had rich avocations that they pursued with passion? How many of them consciously chose to immerse themselves in environments that were uncomfortable and challenged their beliefs? In all likelihood, not too many; the ones who did stand out from the crowd.

The reason not every leader engages in a growth mind-set is simple: as we become increasingly successful we come under pressure to use those CABs that made us successful. We start filtering out everything that seems extraneous to doing what we need to do to succeed. But the science of success is pointing out that, in order to succeed in complexity, we must be open to learning. Success in the Social Age is defined by the ability to challenge and overcome the limiting tendency we all have to repeat what has made us successful in the past. This means constantly looking to change the perspective from which we take in new information and enlarging the CABs on which we rely.

IN SUMMARY

The Social Age has moved us from a world of linear challenges—difficult but knowable and subject to defined probabilities for different outcomes—to a world of complex challenges that are unforeseeable and unforecastable. Complex challenges are recognizable from three characteristics: independent factors, the intertwining of the independent factors, and the emergent outcome that results from the intertwining. Over time, the sum total becomes greater than any of the original driving forces.

The danger when confronting complex challenges is reverting to the strategy with which you entered the situation. Revising and doubling down on an existing strategy is our most common response to an emergent complex situation and is frequently a nonproductive one. A Social Leader approaches new situations from a mind-set of openness. This is a learned practice, one that requires adding to or expanding the CABs in our repertoire to include those that allow us to cultivate creativity (recognizing a wide array of connections), aesthetic judgment (using a number of mental models to recognize patterns, and purpose), and purpose (connecting what we are trying to achieve to something larger than ourselves).