6

Dealing with Discontinuity: Leading from a State of Mindfulness

Do not dwell in the past, do not dream of the future, concentrate the mind on the present moment.

BUDDHA

TOM AND LISA MEET

Three weeks after their first meeting, Tom Lee, VP of sales, and Lisa Charles, VP of purchasing, decided that they would construct a plan for the new RFID effort and pitch it to the other team members. Tom had spent the intervening weeks talking to customers and anyone else he could about this new direction. Lisa had gathered information from her team on all of the relevant parts of the company that would be impacted—basically everyone—and tried to put it into perspective with the technical requirements that Gene Koss had his engineers work up. True to his word, Gene had delivered the specifications for what IKU would need to enter the bulk package smart label business within a month. True to his reputation, the specs were incomplete.

Lisa was already in the conference room when lunch and Tom arrived at the same time. “You certainly have your timing down,” smiled Lisa. “I am glad we decided to get together on this. We may get more done, just the two of us. I have been working up a timeline and cost analysis for launching the new division, and I think this may be a very profitable new direction for us.”

“Possibly,” said Tom. “I am concerned about some things, though. Some of the people I have been speaking with are already starting to talk about what will come after RFID. Who knows, but we may be chasing something that has a short life span. And I think there is going to be some pressure on privacy issues. The latest government data-collection scandal has gotten everyone I talk to nervous.”

Lisa tried to redirect Tom to the here and now. “Tom, we have customers responsible for 43 percent of our revenue insisting on these new package labels and, after investments, we could be profitable on this in eighteen months. The only real challenge I see is bringing Luther King from operations along. The last time we made a significant change and set up some production in Bangalore rather than Hong Kong he was furious, and was not at all cooperative. I am not sure where we will settle the new division, but Luther is likely to resist again.”

“Well, Lisa, I remember that decision as being controversial and rushed. Over the last three weeks Luther has been in contact with Gene, and it seems all right. We should stay focused on this effort and not rehash the Bangalore project.” Tom went on, “Still, I wonder if we should consider expanding this beyond textiles. If we really can develop bulk RFID label production cheaply with data ties to individual item labels, we might find a lot of new markets.”

Lisa could feel her temperature rise. Tom’s constant focus on getting every possible person on board was making her crazy. She thought to herself, “This will never get going if everyone needs to have a hand in it. Everyone will do their part once this is under way.” Lisa knew she needed to calm down before going on, so she started to recheck some of the figures she had brought to the meeting.

Tom stared at Lisa for a full minute, waiting for a response, and then said, with a bit of a laugh, “Hello, Lisa? Are you still with me?”

Lisa snapped back from wherever her mind had gone and said, “Yes, Tom. I was just trying to think through the implications for the incomplete specs we got from Gene’s team.” In truth though, she could not recall what she had been thinking.

“Well,” said Tom, “you’re right of course about that, and possibly about Luther too. Let’s go through all of the things you’ve put together and see what conclusion we come to. All I am asking is that we look over the horizon a bit.”

“Fine,” said Lisa. “Let’s see how far we get and then we can share our thinking with Gene and Mary.”

“Yes, and I’ve been wondering if there are others we should add to the team,” said Tom. Lisa sighed and ate some of her salad.

AN AGE OF DISCONTINUITY

This Social Age is more than the intersection of social connectivity and seemingly limitless technological innovation. It is a time of continuous and recurring disruption to the competitive landscape. These disruptions are frequently called “discontinuities”—complete breaks in the expectations and trend lines we have relied on to create plans and guide actions.

Writing in 2008, Nassim Nicholas Taleb called these discontinuities “black swans,” because historically such radical and unexpected departures from the norm were atypical.1 However, Mike Canning and Eamonn Kelly of Deloitte Consulting, writing just five years later, made a rather different judgment: “Having recently concluded an analysis of the major trends reshaping commerce, we are convinced that the global business environment is experiencing major discontinuities …”2 The business environment discontinuities we experience are driven not only by the forces of the Social Age but are compounded by the innovations our competitors—and, even more importantly, companies that formerly were not competitors—engage in to address the discontinuities they experience. According to Will Mitchell at Duke University, “Organizational innovation involves discontinuous changes in business practices.”3

The traditional leader, in the role of general, takes up the tasks of creating plans, providing direction to the troops on achieving the objective at hand, and dealing with obstacles or variances that can be predicted. But how does a leader address the world of discontinuities—where objectives shift, where both the “troops” and the customers expect to be engaged in the conversation, and where obstacles are not only unpredictable but come from unpredictable sources?

The answer, of course, lies in acting less like a general and more like a mayor. The leader as mayor has a broad direction in which he is leading his constituencies but works at remaining mindful of the changes in the world around him—changes in the sentiments of his constituencies, the emergence of new competitors, and unexpected directions in which competitors are heading.

To Plan or Not to Plan

As we check in with two of our leaders from IKU, we see a tension that is often top of mind in leaders today: How much should we plan? In the previous case, Lisa is arguing to take the information at hand and create a plan with timetables, costs, and deadlines. Tom is arguing to stay loose, believing that the world will change twice before the plan comes to fruition and looking for “weak signals”—low-level information that may not seem relevant at the moment but could change everything in time.

Of course they are both right. You cannot move forward unless you know what you want to do and where you are going. However, in a world of frictionless information exchange, multifaceted connections, and rapid technological, social, and information advances—that is, a landscape of discontinuity—it is harder than ever to make long-term plans. As we examine the productive CABs Lisa and Tom use in this situation, we will recognize the mindfulness tenet.

Mindfulness as a term has been gaining in prominence and becoming increasingly associated with leadership rather than sixties-style counterculture. The Economist ran an article in November 2013 on what it called “The mindfulness business,” catapulting the topic into the hallowed precincts of capitalism and market economics.4 But while articles such as this tend to associate the growing importance of mindfulness with the stressful and nonstop environment of the corporate world, we take a different approach. We see mindfulness as a state necessary for addressing complexity and disruption.

To recap, we refer to mindfulness as a four-faceted awareness:

• Temporal awareness: being in the moment; for example, Tom looking at the current actions of his colleague Luther rather than at Luther’s responses from the previous major project

• Situational awareness: reading the situation and forming an unbiased view of all possible impacts; for example, Lisa gathering information from across the company on the impact of the new strategy

• Peripheral awareness: understanding the potential impact over the horizon; for example, Tom talking to customers and others about their reactions to IKU’s new strategy

• Self-awareness: appreciating one’s own thoughts, emotions, and beliefs, and recognizing the impact of one’s values on actions; for example, Lisa taking a moment before responding to Tom when she felt her anger rising

Physics of the Mind

Classical physics is the study of matter and its motion through space and time, and of related concepts such as energy and force. Analogously, mindfulness is an attempt to understand our perception of the world as it operates through time and space (awareness) and relates to energy and force (values). When a physicist wants to understand how and why a particle is behaving, she asks, “What is its motion (the time and space it occupies) and what forces are acting on it, with how much energy?” We are going to ask the same questions of ourselves to understand our own perceptions—to look at the way we interpret the world around us.

First, let’s look at what we mean by perception. When we become aware of a conversation, action, or behavior (CAB) that has been originated by someone else, we interpret it. We try to understand what occurred, why it occurred, and what it means to us; then we respond. For example, imagine receiving the following e-mail from your boss: “I was wondering about the progress of your report—are things going well?” Did you just receive a show of concern, an expression of sympathy for being overworked, a reprimand, friendly encouragement, an expression of panic based on a looming deadline, or an attempt to remain tightly in control of the situation? Suppose you reply, “I have it covered, thanks.” Did you just try to allay a concern, acknowledge a friendly gesture, tell your boss to back off, defend yourself from a reprimand, or create some space to work without your boss breathing down your neck? The answer depends on a combination of intention and interpretation.

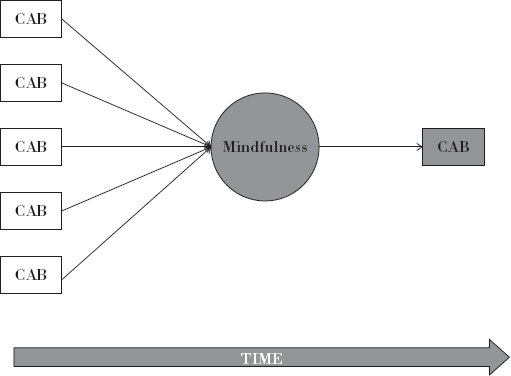

How is this like physics? You may recall seeing a diagram in a high school textbook of a pool table and two balls, one moving and striking the other, which then moves. The physicist asks the question about where the two balls are and the forces are that are acting on each of them. With this knowledge the physicist can explain what happened and what the consequences of this interaction will be. We will be asking the same questions about CABs. For us, the person originating a CAB is the first ball in motion, which provides us with intention. The individual reacting to the CAB is the second ball, which moves in response to the first; here we will be looking at interpretation. The diagram below outlines this set of interactions in its simplest form.

FIGURE 6-1 Mindfulness and CABs

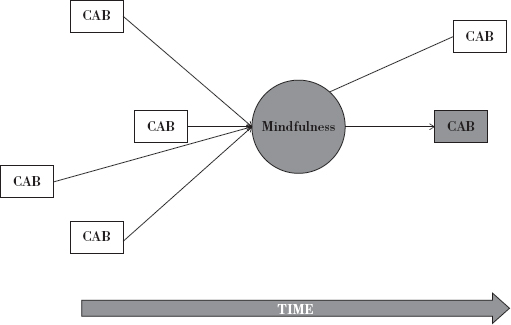

Here we become aware of a number of CABs. We interpret these based on our own values and originate a CAB in response. Of course, the world is not that simple. In reality, the CABs that impact us look something like this:

FIGURE 6-2 Mindfulness and CABs

Some of the CABs that influence us will be close to the point at which we take action and relevant to the matters at hand. Others will be on the periphery of our awareness, as they may not be directly or immediately relevant to the matters at hand. Some CABs will have occurred some time ago and may still be impacting us. Finally, some of the CABs that impact us may have not yet occurred—they are CABs we anticipate. How we react to this complex set of CABs is based on our interpretation of them. Our interpretation is in turn based on two things: the CABs of which we are selectively aware and the values we use to filter others’ CABs.

Being aware of the CABs that impact us and the way we are impacted is how we portray mindfulness as an active aspect of leadership. Jeremy Hunter, from the Drucker School of Management, describes mindfulness as being present and aware of one’s self, others, and the world; recognizing in real time one’s own perceptions, biases, and emotional reactions; and realizing the actions one needs to take to address current realities effectively.5 Mindfulness enables leaders to rapidly assess and respond to situations by stepping back into a zone of awareness, tuning in to what is happening, and watching and regulating their perceptions, thereby responding rather than reacting. Let’s get back to the four-faceted nature of mindfulness:

- Temporal awareness—staying in the present moment

- Situational awareness—focusing on CABs that are directly relevant to the situation

- Peripheral awareness—tuning in to “weak signals6

- Self-awareness—understanding your own values

Let’s look at each of these in turn.

TEMPORAL AWARENESS

There is a growing body of knowledge concerning the positive effects of mindfulness. The concept of mindfulness presented in this literature deals primarily with what we refer to here as temporal awareness, the aspect of mindfulness that involves being present in the moment and remaining in cognitive control. Temporal awareness is the antidote to mindlessness. Mindlessness is a common, pervasive, important but potentially destructive force.7 When we act mindlessly, a common event triggers an automatic reaction. We are often not fully aware that we are reacting, because the whole process of perception–interpretation–reaction has become hardwired. It’s a bit like driving a familiar route and not remembering the drive or eating a meal and not recalling putting the fork in your mouth. We see an example of this in our IKU case when Tom says to Lisa, “Hello, Lisa? Are you with me?” Lisa’s mind began to wonder and she was no longer “in the moment” until she “woke up.”

With all that we need to do in a day, autopilot can come in handy. These innocuous examples of mindlessness are geared toward conserving our energy so that we do not expend it on trivial tasks such as driving to the office. However, mindlessness can also become a habit, and its dangers are readily apparent. When we act mindlessly we act out of routine, disregarding new information and thereby making our habitual CABs unproductive. Acting mindlessly also means we are unlikely to recognize the novelty of a situation, and possibly may respond inappropriately or, more importantly, fail to learn from the situation. Finally, when we allow our brains to automatically select a response for us without our conscious control, we frequently act out of emotion rather than reason. Think back to a time when you have tried to deal with an unexpected disruption, and recall how easy it is for emotions to take over and hijack the brain’s reasoning process.

For example, Hunter describes a series of experiments conducted by several other researchers in which individuals trained in temporal mindfulness are compared to untrained ones in a situation known as the Ultimatum Game.8 In this game, two people—known as “the proposer” and “the responder”—are paired. There is a fixed sum of money and the proposer makes an offer to split the funds with the responder. If the responder accepts, each gets his respective share; if not, neither receives any funds. In the experiment, the “proposer” is always a confederate of the researcher and is told to offer an amount that is less than a fair share.

Logically, the responder should accept any offer that is above zero, with the understanding that something is better than nothing. However, only one in four responders accepted offers that were less than 20 percent of the available funds; all of the others refused such offers, feeling they were too unfair. These responders were unable to separate an emotional reaction to being treated unfairly from their behavior. The one in four who accepted the offer had been trained in mindfulness and was able to successfully regulate their negative emotional reactions. As Bill George, professor and former Medtronic CEO, observed in one of his Harvard Business Review blog posts, “The practice of mindfulness … teaches you to pay attention to the present moment, recognizing your feelings and emotions and keeping them under control … when you are mindful, you’re aware of your presence and the ways you impact other people.”9

Remaining in the moment helps to uncouple events from automatic emotional reactions based on the past. An example of this in the IKU case is the disagreement Tom and Lisa have over Luther’s possible reaction. Lisa is anticipating a negative response from Luther based on his actions during a previous major transition in the company. Tom, however, draws Lisa’s attention to the way Luther is reacting to this new project. While taking into account the history of past reactions is important, it is far more productive to deal with current responses. This is particularly true in the Social Age, when drawing trend lines and planning from past experience is more challenging than ever.

What can we do to avoid automatic, mindless CABs? Temporal awareness is itself a learned habit; it comes with practice. The habit of temporal awareness encompasses four elements:

- Recognizing when your mind is on autopilot

- “Seeing” your automatic thoughts and behaviors as if you were looking at someone else’s

- Bringing your attention back under your control and purposefully perceiving what is going on

- Intentionally selecting a CAB

There are many classes and programs on mindfulness, almost all of which focus on what we call temporal awareness. While taking one of these classes is a fine activity, Hunter and his colleagues suggest a simple approach that we also endorse. Try to meditate each day, beginning with ten-minute periods and working up to twenty minutes.10 To do this:

- Set a timer so you are not worried about how long you are at it

- Sit quietly and try to concentrate only on your breathing

- When your mind wanders, and it will, do the following:

a. Recognize that it has wandered

b. “See” where it went—“What am I thinking about?”

c. Return your attention to your breathing

d. Be kind to yourself. Do not become frustrated, angry, or even disappointed that your mind wandered and you were not able to maintain attention on breathing; your mind may wander a hundred-odd times in ten minutes when you first begin

- When your timer goes off, stop and feel good about whatever success you have had

SITUATIONAL AWARENESS

Situational awareness is the second aspect of mindfulness. Here we are talking about being fully conscious of all the CABs that have direct influence on the matter at hand before selecting a particular CAB as a response. Seeing the whole field and responding to what is happening rather than reacting to what you think has happened is the core of situational awareness. In our IKU case we see Lisa using situational awareness when she reaches into all parts of the company to gather details on the impact the team’s strategy will have on different parts of the company.

As we take in the world around us, we selectively perceive the CABs of others that we deem relevant and then interpret these CABs based on our own value system. We then produce CABs of our own based on this interpretation. Using this basic process as a foundation, improving our situational awareness requires that we do three things.

• Remove the blinders. First, we must become aware of the blinders we are using to select which CABs we attend. Blinders are a critical feature of our survival: without them, all that is going on around us would soon overwhelm us. Improving situational awareness requires that we have active rather than passive blinders. Passive blinders are those that we create out of habit or bias and use without thinking. For example, Nokia once owned the mobile phone market because of its outstanding telephone technology. This led to a reflexive blinder about the emerging importance of software and apps to smartphones, an error reminiscent of IBM’s pass on an operating system known as DOS from a very small start-up called Microsoft.

• Focus on the CAB, not perceived intention. Secondly, improving situational awareness requires that we look at what actually happened rather than what we think was intended. Let’s go back to the example we used to open this discussion. Your boss sends an e-mail inquiring about your progress on a report. It is easy to say, “My boss is pressing me on this report” or “My boss is worried about me,” but the reality is, “My boss sent an e-mail asking about progress on the report.” By focusing on the actual CAB, you can begin to put together an unbiased picture of the situation.

• Suspend judgment. There is a well-understood psychological principle that says once we form a judgment about something we tend to see new information as supporting that judgment and it takes an overwhelming amount of contradictory information for us to rethink our view.11 So, tempting as it is, we can improve our situational awareness by working to hold off judgment until we gather as many actual CABs as possible. Consider forming working hypotheses rather than judgments, and continue to look for contradictory information.

PERIPHERAL AWARENESS

“Because that’s what living is! The six inches right in front of your face!” A great Al Pacino line from the movie Any Given Sunday. Unfortunately, it’s more complex than that. Figuring out what is relevant information amidst all of the weak signals around us is harder than it has ever been. Let’s look at an example. The digital video recorder came into existence and the recording, storage, and retrieval of large volumes of televised programming became simple. For whom was this relevant? Every broadcast advertiser in the world, all of their advertising agencies, and all of the companies engaged in measuring media consumption understood this development as deeply relevant.

What about television writers? If you are a writer for a scripted TV show, does this matter to you? Digital video recording would be an easy thing for a writer to ignore. Easy, that is, until the advent of binge watching, the phenomenon of fans hoarding multiple episodes or entire seasons of a TV show and watching them all at once. Suddenly, the structure of the shows you are writing needs to accommodate this new way of enjoying programs. Peripheral awareness is about seeing this change coming and paying attention to the CABs that do not directly influence what we are doing today but which have the capacity to change the nature of what we do in the future.

These currently not vital CABs are sometimes called weak signals.12 In his aptly named book The Signal and the Noise,13 Nate Silver describes the challenge of separating relevant information from a background of constant information. Trying to remain abreast of information that might be relevant at some future point compounds this challenge.

Cultivating a habit of curiosity is one of the best antidotes to peripheral blindness. Think about the course of your typical workweek: How many people outside your industry and profession do you speak with? What circle are you drawing your inputs and stimuli from? How many things do you read not directly relevant to your immediate activities? Increasing this number beyond zero is a first step in cultivating a habit of curiosity. In our IKU case we see Tom demonstrating this habit. His natural approach to gathering information on the proposed strategy is to go far afield outside of IKU and ask what others’ reactions are both to the strategy he is considering and, more fundamentally, to the challenges he is trying to address. He is looking at what we call “adjacents.”

Actively looking at adjacents is another way to improve peripheral awareness. Take a piece of paper, write your name and your current goal in the center, then surround this with the people, companies, constituencies, departments, and so on that directly impact your ability to succeed. Take the most important of these influencers and surround them with those entities that most impact them. These second-order influencers are your adjacents. How much do you know about them? Are you even sure you know who they all are? Set a plan to confirm that you have the right list of adjacents and then begin devoting some of your efforts to paying attention to what is going on with them. Your peripheral awareness will improve markedly.

SELF-AWARENESS

Self-awareness is essentially about becoming a witness to our own reactions. Looking at our IKU case, we see a classic productive CAB addressing self-awareness.

Lisa could feel her temperature rise. Tom’s constant focus on getting every possible person on board was making her crazy. She thought to herself, “This will never get going if everyone needs to have a hand in it. Everyone will do their part once this is under way.” Lisa knew she needed to calm down a second before going on …

From a mindfulness perspective, self-awareness involves recognizing our own values and understanding where they come from and how they affect our CABs. Each of us holds a wide range of values relevant to different aspects of our lives. Here we are concerned with those values that affect our ability to succeed as leaders. More than five decades of leadership research14 has shown that there are three internal drivers that play a large role in shaping the values we use in selecting CABs. These three drivers are: our need to achieve, our need for affiliation with others, and our need for power. Each of these is a bit more complicated than it seems on the surface. Let’s look at them in turn.

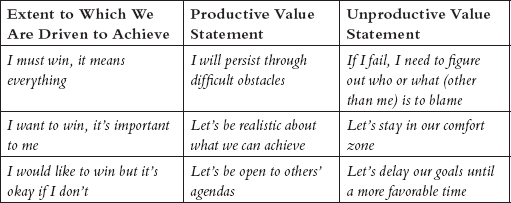

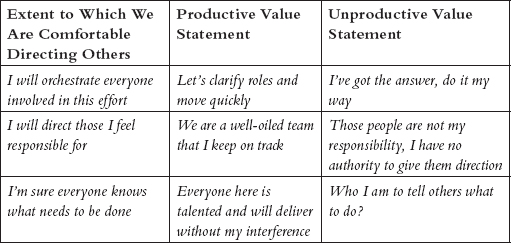

“Fire in the belly,” “Wants to win,” “A real go-getter.” It seems obvious. We look for this drive in the people we hire, we want to be seen this way, and this need for achievement is what should power a leader. Well, yes, … but not completely. Imagine a scale that runs from “It would be nice to win” to “I must win at all costs.” We are all somewhere on this scale, and each point on the scale leads us toward the opportunity for both productive and unproductive CABs. Take a look at the chart that follows:

As you can see, there is not necessarily a “sweet spot” on this scale. The goal is to recognize that we will have biases when selecting CABs as well as in trying to interpret the CABs that we see. Let’s go back to our example of the boss asking about a report status. If you are a must win person, you might interpret your boss’s e-mail as meaning, “Can I blame this person if the report is late?” If you are a want to win type of person, you may interpret this e-mail as your boss saying, “I need to know so I don’t over commit on a deadline we might miss.” If you are a would like to win person, you may see this e-mail as your boss thinking, “Let’s renegotiate this deadline.” The same biases are in play when we select the CABs we use.

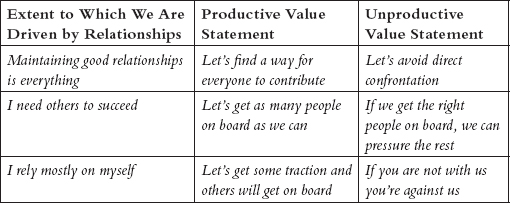

Let’s look at our inclination to be liked and to be part of a group, what psychologists call our need for affiliation. Again, imagine a scale, this one running from “I live and breathe relationships” to “I rely only on myself.” Now let’s look at the chart below.

Again, we can begin to see the potential biases that creep into the CABs we choose when we act without conscious attention to our own values. And again, there is no “sweet spot” on this scale, though the extremes tend to involve a higher number of nonproductive CABs. For a particular situation it may be crucial that everyone is connected, while in another situation it may be necessary, even preferable, to go it alone for a while. Unless you are actively aware of your values, preferences, and biases, it is easy to fall into a predictable pattern of CABs that fit with these values but may hinder your success in that situation.

Further, our need to maintain relationships affects how widely we think when considering whose agendas we care about. If you are less driven by relationships, it is possible that you take into consideration primarily your own agenda (and perhaps that of a close colleague) at the expense of your constituents’ agendas. If you are moderately driven by relationships, you may focus on your team’s agenda ahead of anything else, giving less attention to your own best interests or those of a broader set of constituents. If you are strongly driven by relationships, you may focus on creating broad consensus at the expense of maximizing success.

Finally, when looking at the drivers of our key leadership values, let us consider the very poorly named “need for power.” The concept of our need for power, first articulated by psychologist Henry Murray,15 actually refers to comfort with and preference for getting things done through others. Whereas a person with a high need for power walks into a room, sizes up a challenge, and begins assigning tasks to everyone around, the person with a low need for power is loath to do so. Think of the scale for this value as running from, “Let me tell you what I need you to do” to, “If it isn’t too much trouble, could you help me with this?”

Consider the chart below.

As with the other internal drivers, there is no universal sweet spot on the scale. The extreme ends of the scale contain more opportunity for unproductive CABs, and if we are not aware of our values, we will select CABs that are in line with our preferences but which are not necessarily most productive in the situation.

It’s critical to understand that all three of these internal values drivers—the need for power, for affiliation, and for achievement—are present within us at the same time, interacting to guide our choices.

So how do we remain self-aware? One solution is to recognize that acting in ways consistent with our values makes us feel comfortable, while acting in ways that are inconsistent will make us uncomfortable. You can take advantage of this by periodically asking yourself two questions: “How do I feel about what I am doing?” and “Why?” If you are comfortable with the way you are addressing a challenge, you should be asking yourself: “Is this the most effective way to proceed or simply the one I always use? What might someone choose to do differently and how might that work out?”

If you are feeling uncomfortable with your actions, ask yourself: “Am I acting inconsistently with my usual preferences? Why am I using these CABs? Am I acting productively but in a way that is new and stretching me, or am I acting in a way that is inconsistent with who I am because I am being pressured to do so?”

Once you become mindful of the role your value preferences play in the CABs you select, you can start choosing to act productively rather than out of habit. Brian Little, an award-winning scholar and teacher who has taught at Harvard and Cambridge, refers to this as “acting out of character.” We may consciously choose to act out of character,16 as when an introvert is able to act in an extroverted manner and then returns to her introverted preference.

One final note on self-awareness concerns authenticity. Our internal value preferences make us who we are, guide us toward CABs that are consistent with our self-image (who we strive to be), and allow others to understand how we may react in different circumstances. The goal in addressing the self-awareness aspect of mindfulness is not to change your value preferences. Rather, the goal is to become aware of them so that you can broaden the productive CABs you use and become aware of CABs you use automatically, even though they may not be productive in the given situation.

IN SUMMARY

In short, mindfulness is a core Tenet of Social Leadership that leaders use to help anticipate and react to disruption. Mindfulness involves four facets:

- Temporal awareness—am I “in the moment”?

- Situational awareness—am I conscious of everything that is relevant?

- Peripheral awareness—am I giving enough attention to weak signals (adjacents)?

- Self-awareness—am I acting purposefully or am I reacting out of my unconscious value preferences?

There are techniques to help us improve our ability to be more aware in each of these four areas:

- Temporal awareness—use meditation to regulate where you are placing your attention

- Situational awareness—remove blinders, focus on others’ CABs rather than your interpretation of them, and suspend judgment for as long as possible

- Peripheral awareness—identify adjacents and set aside some energy to keep abreast of them

- Self-awareness—regularly check your comfort level and ask, “Why am I feeling comfortable/uncomfortable with my actions?”