How Prosperous Is Your Community?

If you are fortunate enough to live in a nice neighborhood and have a good job, you probably feel some degree of prosperity. Other residents of your community may be as prosperous as you or more so, while some are struggling just to get by. But, overall, would you consider your community to be prosperous? If out-of-town friends came to visit and you took them on a tour showing them the neighborhoods, retail shops, restaurants, local industries, and other “good” parts of town, would it be hard to avoid the “bad” ones? Several years ago, a mayor gave a group of economic developers, including one of the authors, a tour of his small southern town. He pointed out historic homes, a new city hall, and scenic river vistas, but when he drove through a blighted part of town, he asked everyone in the tour van to lower their window shades for a promotional video—an enterprising, if amusing, approach to community marketing. To address the question of “how prosperous is your community?” we need to first define the term.

What Is Prosperity?

Prosperity is a word with many connotations. If you were to walk down a main street sidewalk and randomly ask passers-by to define prosperity, most people would probably mention wealth, a good job, and other aspects of economic success. You might also hear things such as a self-made person, a rising star, or terms similar to those found in various dictionary definitions of prosperity. Other respondents might have a much different perspective on prosperity. The Buddhist religion includes collectivism and spirituality in the definition of prosperity.1 Yourdictionary.com defines prosperity as “the state of being wealthy, or having a rich and full life.”2 Note the “or” in this definition, implying that wealth and a rich and full life are not necessarily related and either one can be a path to prosperity. Most people, however, might believe that wealth without a rich and full life is a vacuous kind of prosperity.

Each of us can embrace our own definition of personal prosperity, but how do we define community prosperity? More to the point, how should a community define prosperity for itself? Most residents, assuming they do not seek a back-to-nature lifestyle, would probably include a strong local economy with good jobs and economic opportunity for all in their definition of community prosperity. But, is economic success alone enough to call a community prosperous? What about the “rich and full life” and “self-made” aaspects of prosperity in the aforementioned definitions?

A Tale of Two Cities

Figure 2.1 Riverside: A new tech town

Let’s consider for a moment two towns: Riverside (Figure 2.1), where technology companies have moved in creating high-income jobs, and Port City (Figure 2.2), where growth is stagnant and lower-paying manual labor jobs prevail. Given only this information, you might consider Riverside to be the more prosperous community. But, let’s do some fieldwork and find out more about them. From visits to these two towns, we discover that few residents of Riverside are involved in civic activities and there is little sense of community identity. On the other hand, Port City’s residents are active in neighborhood and civic associations that sponsor community improvement projects, festivals, and concerts. People know each other, and there is a sense of community pride. The accompanying boxes paint a more detailed picture of these two contrasting towns.

Figure 2.2 Port City: A town of tradition

The Town of Riverside

Figure 2.3 An old mill in Riverside

Riverside, founded over 150 years ago, grew up around manufacturing firms that originally located there because of hydropower. Over the last three decades, however, employment in Riverside’s manufacturing sector steadily declined as many local firms moved overseas. The ones that stayed eventually succumbed to lower-cost competitors. Despite limited attempts at reuse, the stately old mills by the river eventually fell into disrepair, as did many other parts of the city. Many of Riverside’s residents, watching their children leave for opportunity elsewhere, became discouraged and withdrew from community involvement or even moved away. While Riverside’s economy declined, Danville, a larger city an hour’s drive away, experienced a boom as technology companies grew nonstop, driving up occupancy costs and creating rush-hour traffic congestion. Looking for lower-cost locations but not wanting to abandon a skilled labor force, the owners and managers of Danville’s high-tech firms discovered Riverside’s old mills with their scenic river location and converted them into mixed-use production and office space (Figure 2.3).

The technology companies wanted to staff their new Riverside offices with local residents where possible, but few residents had the appropriate experience and skills, so they asked some of their current employees to transfer to Riverside. Some of these well-paid employees relocated to Riverside, but many others felt tied to Danville because of its good schools and quality of life and therefore chose to maintain their residence there and commute to work in Riverside. The employees that relocated to Riverside tended to cluster in several new gated communities on the west side of town closest to Danville. Riverside benefited from increased tax revenues from the renovated mills, new residential developments, and more daytime retail activity. As a result, the city was able to repair some aging infrastructure and improve its appearance. However, the civic commitment to Riverside from new technology workers was low and they did not get involved in community affairs. Instead, they maintained social ties in Danville and drove back there to visit friends, shop, and otherwise enjoy the larger city’s amenities. While statistics indicated a growing town with high-paying technology jobs, Riverside remained a community with little civic engagement, few amenities, and a stubbornly high crime rate.

Figure 2.4 Port City has a Walkable Downtown

Port City’s history is tied to the maritime industry. Founded over two centuries ago as a mercantile seaport, the city has enjoyed a fairly steady but slow-growing economy. With the help of the state, the city was able to adapt to changing technologies and convert to a small containerized cargo port. The work done by hundreds of stevedores in years past is now done by a handful of crane and equipment operators. While these skilled jobs offer high salaries, many blue-collar jobs in the city’s warehouse and distribution industry offer lower pay. Some residents argue that the town needs to attract companies with higher-skilled jobs, but the common response to this is “these warehouse jobs were good enough for my parents, so they are good enough for me.” Port City is a town of modest homes, but civic and social bonds developed over many years remain strong. Recreational sports are important to Port City residents, and the city has an extensive park system to support them. Neighborhood associations are strong and encourage the involvement of residents in civic affairs (Figure 2.4).

Because of relatively lower incomes for most households and fewer wealthy residents, there are not many outward signs of economic prosperity in Port City. Retail stores sell modestly priced merchandise and restaurants serve family-style meals. Except for a small maritime museum and gift shop, there are no galleries, concert halls, or other arts-related venues. However, the city does encourage outdoor seasonal arts and crafts fairs and folk concerts that attract people from surrounding communities to enjoy the scenic old port area, purchase the work of local artisans, and eat in local restaurants.

Would the additional information from the visits to Riverside and Port City change how you would rate the prosperity of these two communities? Which one would you prefer to live in? Numerous surveys and studies have cast light on what people like about communities, and they can help us arrive at a more complete definition of community prosperity.

How Do People Rate Communities?

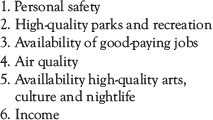

Urban studies expert Richard Florida has examined the factors that influence how survey respondents rate their communities.3 The factors most closely correlated with high community ratings in his study are shown (in the order of strength of correlation) in Figure 2.5. The results were generally similar for urban and suburban residents but with some differences in the factor rankings.

Figure 2.5 Survey: Community factors preferred by residents

Researchers at the Penn State University Extension Service have also examined the factors associated with residents’ evaluation of their community, and they cite two leading studies.4 The first study by McMillan and Chavis found that the following four factors consistently emerged in surveys as attributes commonly associated with a good community:5

1. Membership: a feeling of being invested in the community; having a right to belong and feel welcome.

2. Influence: a sense that they have some say in community issues and that their viewpoints are respected.

3. Integration and fulfillment of needs: the belief that a community has numerous opportunities for individual and social fulfillment, including basic needs, recreation, and social interaction.

4. Shared emotional connection: the sense of a shared history or sense of community with quality interactions.

The second study by The Knight Foundation (Soul of the Community Project)6 identified factors that were most closely correlated with survey respondents’ ratings of “community attachment.” The top five factors (in order of importance) were:

1. Social offerings;

2. Openness;

3. Aesthetics;

4. Education; and

5. Basic services.

Leadership and the local economy were also mentioned by survey respondents, but they did not rank as highly as the previously mentioned five factors.

Hierarchy of Needs

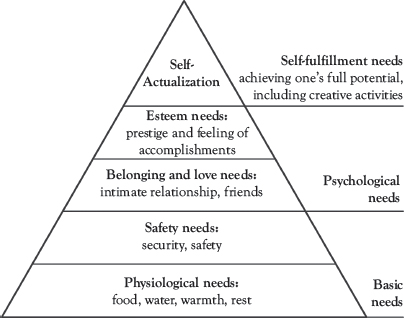

Richard Florida draws a correspondence between how residents rate their communities and psychologist Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs pyramid (Figure 2.6).

At the base of Maslow’s pyramid are basic needs—the necessities of life including food and shelter. One level above that is safety and security, without which little can be accomplished and sustained. Further up the pyramid are the higher-order psychological and social needs of belonging, esteem, and self-actualization, which correspond with the survey respondents’ emphasis on community involvement in the studies referenced earlier. Maslow includes creative activities in the top tier, which points to the role of factors such as arts and recreation in building prosperous communities.

Figure 2.6 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Source: www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html#gsc.tab=0

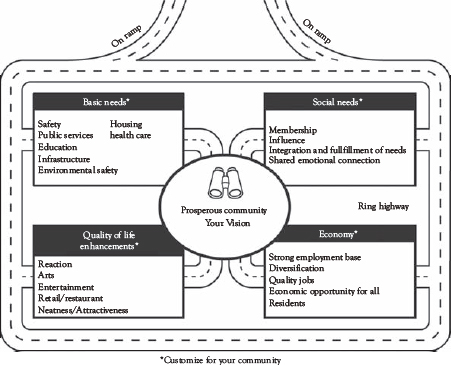

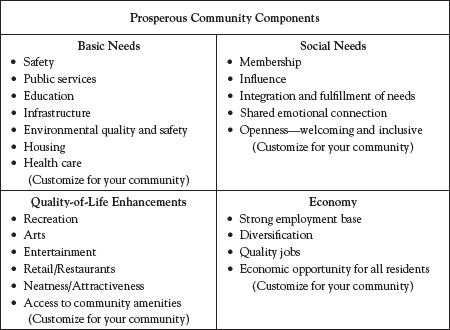

Drawing on the surveys and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs pyramid, we can group the factors that influence how residents rate their communities into the following four prosperous community components:

1. Basic Needs such as safety, public services, and education;

2. Quality-of-Life Enhancements such as arts and recreation;

3. Social Needs such as feelings of community, involvement, and social fulfillment; and

4. Economy including a strong local economic base and good job opportunities for all residents.

Can Money Buy Happiness?

Our discussion of prosperity and happiness leads us to ponder yet again an eternal question: can money buy happiness? Our holistic definition of prosperity might lead us to answer no, but let’s consider some different “philosophical” perspectives on this question. Draw your own conclusions and apply as you see fit.

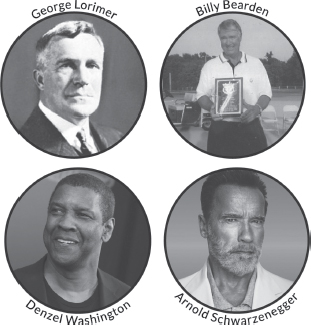

Figure 2.7 Can money buy happiness?

It is a good thing to have money and the things that money can buy, but it’s good too, to check up once in a while and make sure you haven’t lost the things money can’t buy.

—George Horace Lorimer, Editor of the Saturday Evening Post from 1899 to 1936.

When will people realize that time, not money, is what really matters?

—Billy Bearden, Former MVP for the All World Softball League

Money doesn’t buy happiness. Some people say it’s a heck of a down payment, though.

—Denzel Washington, Award-Winning Actor

Money doesn’t make you happy. I now have $50 million dollars but was just as happy when I had $48 million.

—Arnold Schwarzenegger, Actor and former governor of California

Sources: “TOP 25 MONEY DOESN’T BUY HAPPINESS QUOTES | A-Z Quotes.” 2021. A-Z Quotes. www.azquotes.com/quotes/topics/money-doesn’t-buy-happiness.html

Billy Bearden quote from Robert Pittman, coauthor (Figure 2.7).

Building on a Strong Local Economy

While not explicitly considered in Maslow’s pyramid, jobs and incomes are necessary to provide for human needs at all levels. Food, shelter, and other basic needs do not materialize out of thin air, except perhaps from the replicator on the starship Enterprise in Star Trek. A strong economy also helps provide opportunities for meeting human needs higher up Maslow’s pyramid such as creativity and accomplishment, which are related to the prosperous community components of Quality-of-Life Enhancements and Social Needs. Arts activities are often supported by a combination of public and private funding. Profitable companies and well-paid employees help support the arts through patronage and contributions. A healthy economy also leads to higher tax revenues that can provide public support of the arts through grants and other forms of assistance. In addition, financially prosperous communities are often more capable of supporting community improvement organizations such as the United Way that provide opportunities for citizen involvement and personal fulfillment.

These connections between a strong economy and prosperous community components help explain why the McMillan and Chavis study cited previously concluded that:

Evidence suggests that businesses and residents place considerable importance on community characteristics that go far beyond simply a vibrant economy. Importantly for many communities, a strong social and aesthetic foundation is critically important to building a healthy and sustainable economy ….

In other words, just as a strong economy helps support desirable community characteristics, the latter also supports the former—it is a two-way street.

While locally-owned businesses may be more committed to staying in their hometowns, location decisions for larger companies with multiple facilities can be quite complex. They seek communities that offer reasonable operating costs and opportunities for favorable profit margins. They typically compare and screen communities on basic operational factors such as labor cost and quality, transportation services and costs, and the availability and price of land and buildings.7 However, for business and personal reasons, after meeting these basic operational requirements, most business owners and managers would naturally prefer to locate in a community offering a desirable quality of life, good educational resources, and a strong sense of civic commitment. In addition, with the pandemic-related emphasis on remote work discussed in Chapter 1, many knowledge workers are freer to move to amenity-rich communities that meet their social preferences. In turn, these skilled workers make the communities more attractive to businesses. This helps explain the conclusion from the Knight Foundation study cited earlier that communities with the highest levels of “community attachment” also had the highest economic growth rates.

How Does Your Local Economy Measure Up?

Financial analysts use many different metrics to gauge the performance and outlook for companies. They know that current performance is not necessarily an indication of future performance—overall economic trends, product demand, and competition can change quickly. Likewise, executives monitor their firm’s performance and external conditions regularly to look for early warning signs that could affect profitability or even their continued viability.

In a similar fashion, communities should monitor their economic performance to maintain and enhance their prosperity. As several examples in this book attest, the sudden closing of a major employer can devastate a community overnight. While not as dramatic, the gradual decline of major industries and other job-providers in a community can have the same effect over time. As with companies, current performance is no guarantee for the future performance and prosperity of communities. Here are some ways communities can monitor their economic strength and vulnerability:

• Track key economic indicators such as the unemployment rate, personal income, and income per capita. Be aware of trends in these measures—up or down—and investigate their causes. Of course, much of the variation in these key indicators can be closely linked to national trends and this has to be factored into any assessment.

• Benchmark these economic indicators against other communities, your state and the nation to see how your community stacks up currently and also to spot trends.

• Track the performance of the industries in your community. Make a list of industries sorted by employment in the community. Data to do this are available from a number of sources such as the U.S. Department of Commerce and U.S. Department of Labor. How are the major industries in your community performing at the national or international level? Are they growing or declining? This will provide clues to the future performance of your local economy and need for diversification or even rebooting.

• Monitor your local economy from the ground up. Stay in touch with employers in your community to see if they are growing or declining. Most employers appreciate a visit from a local economic development professional or volunteer. Confidential surveys can add to the information gained through visits and direct contact.

Complacency can be dangerous. Smooth economic sailing today may mask turbulent waters ahead. Smart communities, like companies, watch for signs of danger—and opportunity—and plan accordingly. For more information on monitoring and measuring your community, see Phillips and Pittman, Chapter 21.8

A Tale of Three Cities

Riverside and Port City are different communities with their own individual set of strengths and weaknesses. Riverside, with its high-tech jobs, rates highly in the economy component but falls short in some aspects of the other three prosperous community components of basic needs (high crime rate), quality-of-life enhancements (limited support for local retail and restaurants), and social needs (limited community involvement). Port City is almost a mirror image of Riverside, scoring well in basic needs (safety) and quality-of-life enhancements (arts and music festivals) but lower in the economy category than Port City with its high-tech jobs.

So, which town would most people consider more prosperous and prefer to live in? The answer, of course, depends on individual preferences. People who emphasize economic opportunities might prefer Riverside even with a high crime rate and lack of social interaction, while others might prefer Port City because it meets their desire for community involvement. As the saying goes, people are free to “vote with their feet” and seek communities that match their preferences. Other people seek to shape their communities to match their preferences and definition of prosperity—and that is a central focus of community and economic development.

We have discussed how a strong economy can help a community achieve the social characteristics that residents desire, which in turn can help build an even stronger economy. It appears that Riverside and Port City have not yet realized this synergy. Now let’s bring a third contender into our community comparison. The city of Overton profiled in the accompanying box has managed to reboot its local economy twice to achieve higher levels of economic prosperity and build a community rich in the characteristics that residents prefer, including quality-of-life enhancements and the social needs of belonging and involvement. No community is perfect and Overton will always face challenges and issues, but it has demonstrated that it knows how to adapt, reboot, and prosper.

The Town of Overton

Figure 2.8 Welcome to Overton

Overton (Figure 2.8) is a survivor. It has transformed itself and rebooted its economy at least twice before, meeting the challenges (and opportunities) from national and global economic trends. Like countless communities in rural areas, Overton started out as an agriculture market town serving the business and personal needs of local farm families. The postwar economic boom and shift to the production of consumer goods provided an opportunity that Overton embraced. Local leaders knew that Overton’s farm families were hard working and resourceful. When the combine breaks down in the middle of a harvest, farmers find a way to fix it and get the job done. Not only were residents extremely productive and resourceful, their cost of living was also lower and wage scales more competitive than their counterparts in higher-cost urban areas. Overton saw a way to capitalize on the labor force asset and strengthen its economy; so, with help from the state government, it developed programs and incentives to entice manufacturing firms to relocate there and enhance their competitiveness with a more productive labor force.

New manufacturing jobs with higher incomes fostered growth in other sectors in Overton, including retail, home building, education, and health care, thus creating a stronger and more diversified local economy and more personal wealth. Change is constant, however, and years later Overton’s manufacturers began to move offshore looking for the very thing that helped build Overton’s economy—lower labor costs. Overton’s leaders realized that communities now had to compete in the world of advanced manufacturing requiring higher-skilled labor operating sophisticated production equipment.

Fortunately, economic prosperity had helped build strong civic bonds, and the community pulled together to reboot again. They realized that education and training programs, as well as new industrial sites and buildings, were needed to attract modern advanced manufacturing firms, so Overton built a regional coalition with surrounding communities. They worked together to create an advanced manufacturing curriculum at the community college serving the area and developed a regional industrial park that attracted a large international company with high-paying jobs. Thus, for the second time, Overton succeeded in rebooting its economy, this time in conjunction with surrounding communities in a true regional effort.

The Tale of Three Cities illustrates our point that community prosperity has many dimensions. Based on numerous surveys and studies on how residents rate their communities, prosperity is more than just economic success. Riverside achieved economic success but did not translate that into quality-of-life enhancements and community involvement. On the other hand, Port City had a more cohesive community but less economic progress. Overton, however, was able to achieve true prosperity with a strong economy, quality-of-life enhancements, and social needs through citizen involvement. Recreational boaters sometimes use the phrase getting up “on plane.” Many modern boats start out plowing the water like older wooden boats, but as they gain speed, they come up on plane, guiding on the surface for greater speed and maneuverability. We can say that Overton has come up on the plane of community prosperity and is ready to face the future confidently.

A Roadmap to Community Prosperity

Let’s dig a little deeper into the four components listed previously that constitute our definition of community prosperity. Figure 2.9 lists some major factors or characteristics under each component that contribute to community prosperity. The list is not comprehensive, nor is it tailored to a specific community. A principle of community and economic development is to build a community that meets the priorities and vision of its residents, not one that meets a generic checklist. Therefore, to apply Figure 2.9 to your particular community, it should be customized to include prioritized factors that are more highly valued by your community and omit or minimize factors that are not highly valued. For example, residents of a suburban community might desire more close-to-home retail shopping and restaurant options yet be content with driving to the adjacent metro area for arts and entertainment.

Each factor can be further defined in more detail. Infrastructure can include transportation, public utilities, and telecommunications, and those categories can be further subdivided. For example, transportation infrastructure can include highways, roads, airports, public transportation, and so on. For a large city airport facilities and public transportation might be a priority, but for a small town local roads might be the focus. A large city might want to improve its higher education offerings, while a small town might limit its focus to K-12 education. Customizing and prioritizing the community components and factors should be accomplished by following the community development processes of gathering broad input, making inclusive group decisions, and creating a shared vision for the future. If resources were unlimited, any community could shoot for the moon and pursue excellence in all of the factors, but in the real world, budget constraints prevail. Creating a shared vision helps a community decide what components and factors to focus on and set budget priorities.

Figure 2.9 Prosperous Community Components

Now let’s put these community components and factors together to create a roadmap for community prosperity. Figure 2.10 shows the four components surrounding and supporting a prosperous community.

The ring road and interior roads shown in Figure 2.10 illustrate the connectivity among the four prosperous community components. We have discussed the numerous connections between the economy and the other components a strong economy generates: income and tax revenues to support basic needs, such as public safety, and quality-of-life factors such as retail and restaurants. The economy and social needs components are also interconnected as the Knight Foundation study referenced earlier concluded.

Figure 2.10 Roadmap to community prosperity

The Roadmap as a Decision Tool

Ring roads have on-ramps, and in Figure 2.10, they illustrate a useful aspect of the prosperous community roadmap—a filter or tool to help make important strategic and budgeting decisions. To understand this, let’s look at two examples. First, consider a community whose local privately-owned hospital is experiencing financial difficulties and is requesting public-sector support. Elected officials in the community could make that decision themselves, or they could create a citizens task force to study the issue and offer options and recommendations. The task force could include representatives from the local medical community, bankers or others with financial expertise, and perhaps marketing experts to suggest ways to generate more revenue. This approach would directly address the basic need of health care but also relate to the social needs component by increasing citizen involvement and influence. Residents might feel more comfortable with the decision to support or not support the hospital with public funds knowing that a group of their peers with the appropriate expertise had input into the decision.

In addition, the economic impact of the hospital should be considered. Hospitals bring money into the local economy through insurance payments and payments from patients in the larger regional hospital market. This money supports health care jobs, and those employees spend money in the local economy on housing, food, and numerous other consumer goods. The question of whether to financially assist the hospital, therefore, should be evaluated on how it affects all prosperous community components, not just the basic need of health care.

As a second example, consider a community embroiled in a heated debate over developing a highway by-pass. Some residents might support the by-pass to help alleviate traffic congestion, while others, especially in-town merchants, might be opposed because of the potential negative effect on existing businesses. At first blush, the by-pass might be viewed as a transportation and quality-of-life issue with some potential effect on local businesses; however, there could also be larger economic issues at stake. The by-pass could open up access to land favorable for industrial development, making the community more attractive to new businesses looking for good sites and good transportation access. It could lead to overall economic growth that could benefit existing local businesses and encourage new ones to open.

These examples illustrate how the prosperity roadmap can assist communities in making decisions. Issues such as a highway by-pass or supporting the local hospital generally affect a community in many different ways along the ring road, and these interactions among the prosperous community components should be taken into consideration.

There is a second important decision-making element underlying these examples. When deciding on matters such as the by-pass or support for the hospital, consideration should be given to how a community wants to grow and develop—its vision for the future (see accompanying box). In the case of the by-pass, does the community want to grow more quickly and attract new businesses and chain retailers along the by-pass, or would it prefer to remain a tourist destination with a quaint downtown retail district? Community residents opposed to the by-pass might argue that it will create noise and pollution, while those in favor might argue that it will relieve traffic congestion. These are certainly valid issues, but chances are an underlying bone of contention is different visions for the community.

Community Visioning

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” is a question mothers, fathers, aunts, and uncles often ask children in their families. This question has prompted countless young minds to think about what their future might be—or what they can make it be. Many companies also think about what they aspire to be when they “grow up,” and become bigger and better organizations. Here are some examples of company mission statements or visions:

IKEA: “To create a better everyday life for the many people.”

Nike: “To bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world.”

Tesla: “To accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy.”

A vision can help keep an organization’s employees focused on a shared purpose and promote teamwork. Studies have shown that employees who believe in their organization’s vision statement are more engaged than those who do not.

A vision statement can have a similar positive benefit for a community working to move forward and achieve prosperity. A community vision statement can be brief, reflecting general values such as—Columbia, Missouri’s “Columbia will be a connected, informed and engaged community” or it can be more detailed like these excerpts from the vision statement of Lakewood, Colorado:

We envision a community that is a great place to live; a community that cares about the environment, and a community that maintains a high quality of development.

We envision a growing and diverse business sector that provides residents with a wide range of products and competitive services.

There are proven procedures a community can use when creating a vision in order for it to be motivating and successful. A process of developing the vision should be inclusive, giving everyone in the community a chance to express their opinion on the community’s future. The vision statement must be realistic, but at the same time be challenging to inspire the community to work hard to achieve it. More information on community vision statements is in Chapter 3’s discussion of the community development process.

Sources:

R. Phillips, and R.H. Pittman. 2015. An Introduction To Community Development. New York, N.Y.: Routledge.

“22 Vision Statement Examples To Help You Write Your Own | Brex,” 2021. Brex.Com, www.brex.com/blog/vision-statement-examples/

“Community Vision—Master Plan | The City Of Lakewood, Ohio,” 2021. Lakewoodoh.Gov, www.lakewoodoh.gov/community-vision/

Now let’s mix the roadmap to prosperity together with visioning and planning to create a comprehensive community decision-making and budgeting tool. Elected officials can be bombarded with requests to fund this or that cause or project. Individually, they can be worthwhile; and if they are not funded, their proponents often proclaim: “How could you not fund this wonderful project?” The problem is that there are many worthwhile projects but limited budgets. Too often, political connections and lobbying determine budget priorities with little thought to synergies and long-term community benefits. Just as well-run companies make investment decisions based on returns—how they will contribute to profitability and the company’s mission—communities should make budget decisions based on how they contribute to prosperity. Here are three steps to accomplish this:

1. Create a vision and plan for the community as outlined in the accompanying box and discussed in Chapter 3.

2. Use the vision and plan to customize and prioritize the prosperous community components and factors list in Figure 2.9. As an example, consider a town named Bridgecreek with the vision to become the leading upscale tourist destination in the state by attracting tourists with fine dining restaurants, art galleries, and recreational amenities. To facilitate this vision Bridgecreek could prioritize quality-of-life factors, such as neatness/attractiveness, and basic needs, such as environmental protection and public safety.

3. Use the customized list of prosperous community factors as a filter to help make strategic and budget decisions. In Bridgecreek, a plan to create a streetscape with enhanced off-site parking in the downtown area would be a higher budget priority rather than a developer’s request for incentives to build an amusement park. Interactions among the prosperous community components as discussed earlier should also enter into Bridgecreek’s budget decisions. A more attractive downtown with sidewalk cafes and other amenities could entice more local residents to congregate there, increasing social interaction and reinforcing the sense of community.

Using a community’s vision and customized prosperity roadmap lends openness and transparency to the public decision-making and budgeting process. To make a point, the authors sometimes ask elected officials if they have ever gotten undisputed unanimous support for a first budget draft. The answers range from incredulous looks to howls of laughter. Community residents and stakeholders disagree on budget priorities for many reasons, but as discussed previously, they often do so because they have different visions for the future of the community. The simple question “does this proposed expenditure help us achieve our community’s vision?” can make life much simpler for elected officials.

Getting the Mayor Off the Budget Hot Seat

During a break in a seminar taught by the authors, the mayor of a small town close to a metro area told the author that he had to prepare his first draft budget, and it could make or break his young political career. He explained that the town was divided between residents who wanted to build a youth sports complex and those who wanted to develop a speculative industrial building to attract companies, and the town did not have the budget to do both. We told him there was a relatively simple way to answer that question to help get him off the hot seat. We suggested that he first engage the community in a visioning and planning exercise to address, among other issues, if the consensus was to: (1) remain a bedroom community with residents continuing to commute to the metro area, or (2) attract more businesses to the town and give residents options to work locally, and to diversify and expand the town’s tax digest. If the consensus was the latter, then it would make more sense to start the economic development process and develop the building to help attract a company to the town. He thanked us profusely and said, “Now I can say I’m carrying out the will of the people,” to which we replied, “Shouldn’t all budget decisions be based on that?”

Newly elected officials sometimes complain to us that the pressure to take positions on issues during the campaign and after taking office often forces them to make decisions too quickly without adequate knowledge or public input. Occasionally we read about newly appointed CEOs spending their first weeks on the job talking to as many people in the organization as they can before making any decisions. Perhaps decision making in many places could be improved if elected officials would start their time in office the same way to help the community achieve its definition of prosperity.

A Journey or a Destination?

Now that we have explored its many dimensions, we can offer a more concise working definition of community prosperity:

A prosperous community is one that maintains a strong and diversified local economy to provide economic opportunity for all residents, provides for the basic needs of residents, offers quality-of-life enhancements preferred by residents, and meets the social needs of residents through community involvement.

You may think that your community meets this definition, or you may believe it falls short. No community is perfect, and there will always be differences of opinion on how any community measures up and on where there is room for improvement. In this light, we should think of community prosperity as a journey rather than a final destination. Circumstances are always changing—communities will face economic shocks such as the loss of major employers, and “new normals” will bring challenges and opportunities. Communities must adapt and even reboot in response to changing circumstances as Overton did in our Tale of Three Cities.

To make our definition of community prosperity more dynamic, we could add to it the ability to adapt to changing internal or external circumstances to sustain prosperity. Even a gold medal-winning athlete must train for the next Olympic event at a new venue with new competitors. Just as a gold-medalist celebrates his or her tremendous accomplishment while preparing for the next competition, communities should celebrate their achievements and milestones but continue their efforts to become even more prosperous. Now that we have a working definition of community prosperity and understand its underlying components, the question becomes how to attain it and sustain it—how to get up and remain “on plane” like a sleek speedboat. That is the focus of the remaining chapters.

Prosperous Community Toolbox

Read, Reflect, Share, and Act

Chapter 2 challenges us to think about the definition and level of prosperity in our own communities. Prosperity means different things to different people, however experience has shown that by using community development tools a consensus definition of prosperity and a commonly-shared vision for a community can usually be reached. This chapter offers tools that can help your community build its own definition of prosperity.

The Chapter 2 tools will help your community create a first draft of your roadmap to prosperity with input from all who call your community home, and to create a tracking system to measure your community’s prosperity.

2.1 Create a prosperous community website to help gather survey responses in 2.2 below and from the community visioning exercises in Chapter 3 and other public input, and to keep residents informed of community prosperity efforts and programs.

2.2 Based on extensive community input, identify and prioritize the community components and factors that residents believe best define your community’s prosperity. In other words, create a first draft of the prosperous community components and factors table such as Figure 2.9 for your community. Look for common elements in all the community feedback and comments as input for developing a vision and plan for the future of the community (Chapter 3 toolbox). Revise and finalize the prosperous community components table after completing a community visioning exercise in Chapter 3.

2.3 Create a spreadsheet or other model to assess and track the strength of your community’s economy in the ways suggested in the box “How Does Your Community Measure Up” in this chapter. Find a suitable local person or persons (committee) to build, operate and update the model and issue reports to the local officials and the public. Decide on the measures to be tracked (economic, demographic, social well-being and other desired measures). Identify and report trends in key measures, positive or negative. This will be an integral part of the visioning exercise in Chapter 3.

Visit https://www.prosperousplaces.org/rebooteconomics_tool-box/ to download worksheets and templates for the Chapter 2 tools.

The Real Overton

The example of Overton in the Tale of Three Cities is based on the real-life community of Tupelo and Lee County, Mississippi. Tupelo’s success in applying community and economic development best practices to achieve prosperity and reboot has been extensively chronicled in articles and books. Much of the prosperity in Tupelo and Lee County has come about through regular and comprehensive community visioning, goal setting, and planning. The city and county believe in establishing a foundation for prosperity through the community development process, and then building on that with the economic development process—the subjects of Chapters 3 and 4. A regional foundation for community development called CREATE was established decades ago to encourage strategic planning and collaboration around shared goals. Tupelo’s vision and plan for prosperity centers around the following six themes:

1. Orderly, efficient land-use patterns;

2. Economic vitality;

3. Neighborhood protection, revitalization, and housing opportunities;

4. High-quality design and development;

5. Efficient and accessible transportation; and

6. Regional coordination.

Tupelo and Lee County have utilized the tools in the toolbox to embrace and benefit from change and achieve sustainable prosperity. As a result, Tupelo has been named an “All American City” five times by the National City League.

Sources:

V.L. Grisham, and R. Gurwitt. 1999. “Hand In Hand,” Washington, D.C.: Aspen Institute, Rural Economic Policy Program.

Author discussions with Tupelo/Lee County officials.

1 R.S. Gottlieb. 2003. Essay. In Liberating Faith: Religious Voices for Justice, Peace, and Ecological Wisdom 288, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

2 www.yourdictionary.com/prosperity” (accessed April 12, 2021).

3 Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-09-19/what-makes-us-the-happiest-about-the-places-we-live (accessed April 12, 2021).

4 Educator, Walt Whitmer Extension. March 31, 2021. “What Makes the ‘Good Community’?,” Penn State Extension, https://extension.psu.edu/what-makes-the-good-community

5 D.W. McMillan, and D.M. Chavis. February 10, 2006. “Sense of Community: A Definition and Theory,” Wiley Online Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

6 “Soul of the Community,” Knight Foundation, https://knightfoundation.org/sotc/ (accessed April 12, 2021).

7 R.H. Pittman. 2012. “Location, Location, Location,” Management Quarterly, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203049556

8 R. Phillips, and R.H. Pittman. 2015. An Introduction To Community Development, New York, N.Y: Routledge.