January 2013: The downtown was relatively empty, with a few antique stores hanging on along with several law offices near City Hall. The area had been prosperous once, bustling as a regional center with the railroad running right through town. The downtown, surrounded by hundreds of historic homes from the early 1900s, was like so many other small to mid-sized towns throughout rural America—a shell of its former self. Fast forward five years and this town became a media darling and tourist destination. How did this happen and what prompted this rather dramatic makeover within such a short timeframe?

The answer lies in … community development! Laying the foundation is the starting point for responding to opportunities (even those no one could see coming) and creating opportunities for paths forward to prosperity. This is what community development is all about—building a strong foundation on existing assets and working to improve conditions and opportunities. To find out more about this turn-around story, see more details and the reveal at the end of this chapter. But before you skip to the end, let’s discuss some “bricks-and-mortar” fundamentals of laying a solid foundation for a prosperous-ready community.

This chapter shows how the process of community development, including creating a vision and addressing community issues through an inclusive strategy, paves the way to the outcome of a prosperous-ready community. This solid foundation then provides the basis for the process and outcome of economic development, increasing the flow of money into the community, thus creating new jobs and higher incomes. And it’s about more than just money, because by engaging in community development, social cohesiveness (sometimes called social capital) and other desirable community aspects and assets are strengthened. All these elements, or “capitals” of a community, are ingredients for the recipe of place making or creating community prosperity. A beautiful wedding cake is an artful blend of layers and icing. Community development creates the layers, and economic development provides the icing of economic opportunity for all residents.

The field of community development has expanded greatly in recent years as researchers and practitioners have learned more and developed even better roadmaps to community prosperity. The same is true for economic development. Our goal in Chapters 3 and 4 is to outline the basics of community and economic development and identify some tools to help communities practice them with greater success. Detailed information about the theory and practice of community and economic development can be found in the chapter notes and references.

The Fundamentals of Community Development

Community development is both a practice and a field of study. Towns, cities, regions, and states practice it, and numerous universities and organizations offer degree and training programs for elected officials, citizens, and others interested in improving their communities. It is founded on the premise that a city, town, or neighborhood is more than just a collection of buildings; each one is a community of people facing common problems and a desire to improve situations or outcomes. It is about a process—developing the ability to act in a positive manner for improvement—and it is about outcomes too. The latter involves taking action for community improvement to generate desirable results.

There are many strategies and tools for community development including organization and leadership development, visioning, planning, and mapping assets in the community. There are also many proven “best practice” principles in community development such as ensuring public participation with broad representation from all members of the community, monitoring progress, and making adjustments in response to challenges that may arise. The Community Development Society, the oldest professional and scholarly association in the field, provides the following Principles of Good Practice:1

• Promote active and representative participation toward enabling all community members to meaningfully influence the decisions that affect their lives.

• Engage community members in learning about and understanding community issues, and the economic, social, environmental, political, psychological, and other impacts associated with alternative courses of action.

• Incorporate the diverse interests and cultures of the community in the community development process; and disengage from support of any effort that is likely to adversely affect the disadvantaged members of a community.

• Work actively to enhance the leadership capacity of community members, leaders, and groups within the community.

• Be open to using the full range of action strategies to work toward the long-term sustainability and well-being of the community.

You can see quickly from this list that community development is about more than the individual; it is about all members of the community working together for progress.

There are also professional ethical standards in the practice of community development. The Community Development Council offers the following values to guide Certified Professional Community and Economic Development (PCED) practitioners:2

• Honesty

• Loyalty

• Fairness

• Caring

• Respect

• Tolerance

• Duty

• Lifelong learning

Community development focuses on helping residents understand how economic, social, environmental, political, and other factors influence their community. This knowledge can then be transformed into results through coordinated actions for progress. Community development is about much more than social service programs or bricks-and-mortar construction projects. Instead, it is a “comprehensive initiative to improve all aspects of a community: human infrastructure, social infrastructure, economic infrastructure, and physical infrastructure.”3 It is these dimensions of community development that are important for everyone involved in the process to know, and we recommend that when starting a community development process or plan, you share these principles and values with participants.

Being There for Your Community Makes a Difference

Two key success factors in community development are: (1) the belief that something positive can happen and (2) working together and collaboratively to make it so. These are accomplished by being engaged and participating in your community’s place making, or “place keeping” if, for example, you are preserving historic, cultural, or natural assets in a historic district or conservation trust to retain open space. Belief is a powerful force and typically begins when an individual or group of people begin to realize that they can contribute to maintaining or improving the quality of life in their community. Although places can change because of just one person’s actions, community development is best performed as a group activity, with strategies emerging from the decision of a group of people to take action. It requires community wide initiatives, which in turn requires collaboration. The context of community development is broad and inclusive, as it literally endeavors to affect the entire realm of a place. Another way of thinking about community development is to think of it as community building, including building the foundation of a prosperous-ready community.

Let’s discuss for a moment the notion of hope. It’s an intangible element, yet it can exert a dramatic influence on a place, as can its opposite, hopelessness, as indicated in the following example. The authors recently worked with two communities about the same size (population under 50,000) with similar histories of development as railroad and agricultural towns. For sake of discussion, we’ll call them Sunrise and Sunset (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Some communities are sunrise and some are sunset

Both communities have experienced various states of economic decline since the 1970s and 1980s when agriculture transitioned to a larger-scale industrial focus and small industries (such as assembly and components parts manufacturing or textiles) left the United States for Mexico or overseas.4

Sunrise is now doing very well in economic and social terms and enjoying prosperity. Residents have aspirations and developed plans that reflect their hopes and dreams for their community. They’ve built on their assets, which include a significant palette of historic properties from the early 1900s, and they are committed to preserving their historic districts ensuring that absentee owners maintain properties. Not many deteriorating structures in Sunrise! The local government maintains the park system and common areas and decorates for holidays and festivals. By maintaining aesthetically pleasing visuals, they create an environment that is interesting and attractive to others—a strong sense of place. In some ways, they were lucky. Their historic downtown was frozen in time because not much development had occurred for decades, so when they were ready to start revitalizing, the raw material on which to do so was waiting, mostly intact.

Sunset similarly has a varied and deep fabric of historic properties and a parks system designed in the early 1900s during the City Beautiful Movement era. The city was once an attractive destination on the rail line in a bygone era. But, here is what greeted us when we arrived: litter strewn everywhere, graffiti (but not the artistic type like found in some Detroit neighborhoods now on the graffiti trail attracting viewers, tourists, and artists) and dilapidated structures throughout the city. The widespread situation very clearly signaled a lack of any policy enforcement for absentee owners to maintain properties. Envision vines growing over derelict buildings, sometimes right next to well-maintained properties. This kind of blight depresses property values and deters others from investing in the community. Public areas were not maintained, and parks and crumbling infrastructure needed attention. To its credit, Sunset had invested in a new rail station and preserved part of the historic building, but it was quite evident that numerous historic structures had been lost. The charred remains of one historic downtown building serve as a constant reminder to residents and visitors of forever-lost assets.

What makes the difference in these two cities? It’s hard to know the whole story without further investigation of these places, but one thing very clearly emerged. When asked why they embarked on their community development journey, Sunrise stakeholders responded with “because we care about each other.” Likewise, we asked Sunset stakeholders why they had not started community development efforts and the response was “because no one cares.” In fact, they stated that a sense of hopelessness pervaded the community, and many who may have once been interested in taking actions “have lost hope” or left. With these examples, you can see what the presence of caring and hope can do for a place. It doesn’t mean that attitudes can never change, but it does show that how residents feel about their community and each other can heavily influence community development and prosperity.

Hope, caring, and a sense of shared responsibility—these attitudes influence the willingness of a community to take actions and move forward. It really isn’t enough to wait for something to happen, it’s up to residents and stakeholders to make it happen, literally. This is the essence of community development.

Being Ready for Development

A big part of community development and laying the foundation for successful economic development is identifying and nurturing assets in the community. What are community assets? Simply put, they are resources, skills, talents, and experiences inherent within a community’s individuals, organizations, and institutions. Assets also include the stock of monetary wealth of households, organizations, and local governments. There are several types of assets that are considered in community development including human, social, financial, environmental, cultural, political, and physical.5 The stock or level of these assets in a community can be referred to as community capital. Financial assets are critical for supporting community development efforts as shown in the roadmap to prosperity in Chapter 2. Infrastructure, as part of physical capital, is essential for supporting physical development. Also important to community development is achieving a balance between the cultural and political elements or capitals of a community so that a sense of shared purpose can overcome differences and challenges. Experience clearly shows that groups of residents working together toward shared goals generates more desirable community development outcomes. Over 2000 years ago, Aristotle recognized this too, stating that the goal is not about following the rules, but about performing social practices well. Certainly, community development is a social practice and needs to be performed well to be effective! Each of the community capitals can be further subdivided; for example, physical capital can include natural resources as well as the built environment.

While all of the community capitals are important, two are often preeminent: human and social capital. Let’s define them in more detail to see why. Haines describes human capital as:

… the skills, talents, and knowledge of community members. It is important to recognize that not only are adults’ part of the human capital equation but children and youth also contribute. It can include labor market skills, leadership skills, general education background, artistic development and appreciation, health and other skills and experiences. In contrast to physical capital, human capital is mobile. People move in and out of communities, and thus over time, human capital can change. In addition, skills, talents and knowledge change due to many kinds of cultural, societal, and institutional mechanisms.6

Another community asset or capital that is vital to community success is social capital. It would be difficult if not impossible to have much success in community and economic development without some degree of this type of capital asset. It can be defined as the extent to which members of a community can work together effectively7 to develop and sustain strong relationships; solve problems and make group decisions; and collaborate effectively to plan, set goals, and get things done.8 Social capital is often divided into two types: bonding capital among similar groups and bridging capital among different groups. The more social capital a community has, the better it can meet challenges and work around deficiencies in the other types of capital.

Human capital and social capital are different from the other capitals because they describe the abilities of community residents to work together and get things done. It’s apparent that human capital—the abilities and assets of individuals in the community such as leadership and education—is critically important for building prosperous communities. Success would surely be limited if, for example, residents of a community had no leadership skills. As we’ve discussed, groups of people working together effectively drive the community development process, and social capital describes the ability of residents to do that.

Political capital, like human and social capital, is intangible but also very important in the process of community development. Political capital has been described as “a metaphor used in political theory to conceptualize the accumulation of resources and power built through relationships, trust, goodwill, and influence between politicians or parties and other stakeholders, such as constituents.”9 Trust, goodwill, and other aspects of political capital are obviously related to human and social capital.

These three closely related intangible community assets: human, social, and political capitals, can be considered the “software” or human components of the community development process. The other capitals mentioned earlier—financial, environmental, cultural, and physical—are the “hardware” of community development. They are the hard or tangible assets that residents use to create community prosperity as programmed by the software.

How does a community increase its stock of social capital? This is done through the process of capacity building, which is designed to strengthen the problem-solving resources of a community.10 Capacity building can be done through activities such as community and neighborhood organizing, developing formal and informal institutions and organizations, and collaborating toward shared goals.

The Community Development Chain

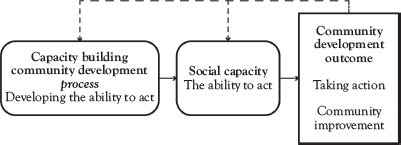

Simply put, the community development process includes two components: (1) taking action to improve the community and (2) developing or enhancing the ability to take action. The process then leads to the outcome of community development—a great place to live, work, and play. But a positive outcome of community development also supports the process—it is a two-way street as illustrated in Figure 3.2 and described as follows:

The solid lines show the primary flow of causality (from process to outcome). However, there is a feedback loop shown by the dotted lines. Progress in the outcome of community development …. contributes to capacity building (the process of community development) and social capital. For example, better infrastructure (e.g., public transportation, internet access, etc.) facilitates public interaction, communications and group meetings. Individuals who are materially, socially, and psychologically better off are likely to have more time to spend on community issues because they spend less time meeting basic human and family needs. Success begets success in community development; when local citizens see positive results (outcomes), they generally get more enthused and plow more energy into the process because they see the payoff.11

Figure 3.2 The community development chain

The community development process can influence the type as well as amount of growth experienced within a community. Prosperous places create their own futures through effective application of the community development process that empowers residents and other stakeholders to change in desired directions—to follow their own roadmaps to prosperity. Development should be goal-oriented, and not change for the sake of change. Community development is based on the foundational principle that residents and other stakeholders have the capability (or can develop it) and responsibility to undertake community-directed initiatives for the good of all residents.

Creating a Community Vision

Once a community understands its assets including the important dimension of social capital, then it’s time to start the visioning process. The biblical adage that those without a vision will perish applies to community development. Communities without a vision may not be destroyed by a plague of locusts, but they are at a greater risk of growth and development happening “to” them instead of “for” them as noted earlier in the book. Understanding your community’s assets is an important place to start because it helps create a realistic and attainable vision. When a community’s vision is coupled with the process of community development and action, good things start to happen. The Orton Family Foundation, a nonprofit organization, believes that “empowering people to shape the future of their communities will improve local decision making, create a shared sense of belonging, and ultimately strengthen the social, cultural and economic vibrancy of each place.”12 They developed the Heart & Soul Community Planning handbook focusing on helping communities actualize this mission in their own places. The organization states, “Vision without action is a dream. Action without vision is simply passing the time. Action with Vision is making a positive difference.” Vision is a guide to making a community what it wants to be, and that is why vision is at the center of the roadmap to prosperity in Chapter 2.

Why just wish for the future to happen to your community? Prosperous communities know that the future is something they can direct and create based on what they want to achieve. Community visioning is therefore an essential element of community development. The process itself can be just as important as the output as it brings together all residents and stakeholders from within a community to discuss ideas, identify challenges and opportunities for improving overall well-being and quality of life.

There are many guidebooks and other resources on the visioning process, some of which are listed in the Toolbox at the end of this chapter. Here, we will share some basic guidelines that have proven effective in numerous community visioning projects across the United States. These guidelines focus on collaboration and consensus building that are vital to the visioning process. Without broad-based participation, getting support and buy-in from others in the community is difficult to do. Community visioning is different and more inclusive than some of the downstream community and economic development efforts such as identifying prospects for an industrial park. Here are the guidelines that can make for a successful community visioning process:

• People with varied interests and perspectives participate throughout the entire process and contribute to the final outcomes, lending credibility to the results.

• Traditional “power brokers” treat other participants as peers.

• Individual agendas and baggage are set aside so that the focus remains on common issues and goals.

• Strong leadership comes from all sectors and interests.

• All participants take personal responsibility for the process and its outcomes.

• The group produces detailed recommendations specifying responsible parties, timelines, and costs.

• Individuals break down racial, economic, and sector barriers and develop effective working relationships based on trust, understanding, and respect.

• Participants expect difficulty at certain points and realize it is a natural part of the process. When these frustrating times arise, they step up their commitment and work harder to overcome these barriers.

• Projects are well timed—they are launched when the time is right for making it happen.

• Participants take the time to learn from past efforts (both successful and unsuccessful) and apply that learning to subsequent efforts.

• The group uses consensus to reach desired outcomes.13

After completing the visioning process, communities should develop a strategic plan to attain their vision with goals and action items attached to each goal. In other words, visioning should not just identify wonderful items that are desirable in the community; it should also include realistic goals and action items with assigned responsibility for them. The visioning process should include financial and other resources for each goal in as much detail as practicable. Evaluation and reporting should be included in the visioning and implementation processes using a format agreeable to the community. It is important to know how much progress is being made toward the vision goals so that recalibrations can be made as needed. Sometimes, the goals may change as conditions do—just imagine how many community and business goals have changed due to the pandemic. Since uncertainty is a certainty, it is important to adjust goals and actions in response to unanticipated developments while keeping the community vision firmly in sight as the target. Completing a visioning process and developing an implementation plan will create a foundation for subsequent growth and development and help a community achieve its definition of prosperity.

Being Creative in Development Approaches

Recall the four main components of a prosperous community in Chapter 2 and the factors or characteristics under each one. Three of the main components—basic needs, quality-of-life enhancements, and social needs—are directly aligned with community development. The fourth component, the economy, relates more directly to economic development. However, as discussed in Chapter 2, the four components reinforce each other and therefore the processes and outcomes of both community and economic development are key ingredients for community prosperity. Community development creates a “prosperous-ready” foundation and economic development draws on this to create jobs, investment, and income. But, the world is constantly changing and creating “new normal” situations, so in this section we want to look at some new ways of thinking about how to build a solid foundation for prosperity. While considering these examples, keep in mind that there are many other creative ways to support development such as sports venues and activities as well as strategies for encouraging tourism to draw in visitors and more money into the community. We just can’t cover them all here.

Arts-Based Development

As we’ve discussed previously in the book, quality-of-life enhancements, depending on community preferences, often include arts and culture. These are also related to the other prosperous community components and can be used to spur creative ways to accomplish community and economic development. Cities and towns around the globe have found that the arts can play a crucial role in local development efforts. The amenities and aesthetics of a place can enhance its overall image and consequently help attract additional development. Some places, including small towns such as Jerome, Arizona or Toppenish, Washington, treat the whole town as an art object with murals and artists venues. Larger places such as Duluth, Minnesota focus on rejuvenating the arts and other quality-of-life factors as part of a larger development strategy. Duluth is a great example of integrating the arts into community development planning and strategy (see the following box). Public art becomes a way to strengthen and define a place. Such is the case of Loveland, Colorado where hundreds of sculptures create a park-like environment in the city and make art a major attraction. This concentration of public art helped attract related companies and activities to Loveland, including specialty arts, bronze casting, and other arts-related enterprises. Silicon Valley may have its cluster of technology companies, but Loveland has created its own cluster of arts-related activities and businesses.

Returning Prosperity to Duluth, Minnesota

Figure 3.3 Duluth, Minnesota

Duluth, located on the western end of Lake Superior, developed as a major port for shipping iron ore to steel mills along the Great Lakes and agriculture products from mid-western states to markets in the United States and abroad. During the 1970s and 1980s, Duluth experienced a number of economic shocks, including the decline of the U.S. steel industry and competition from other ports. A steel production facility located there closed in 1979, leaving 5,000 people unemployed and a contaminated site. Unemployment in Duluth peaked at nearly 20 percent in the early 1980s, by which time the population had declined by over 20 percent from a peak of over 106,000 people in 1960. Tax revenues declined as economic stagnation continued. In 2008, the city faced a $4.4 million budget deficit, and in 2009 Moody’s issued a negative outlook for the city’s bond rating. National industry trends were not kind to Duluth, and the city fell from prosperity.

Duluth clearly needed to reboot its economy and reboot it did. Building on its location as a gateway to the scenic beauty and recreational opportunities along the northern shore of Lake Superior, the city took steps to enhance its appeal to younger residents by promoting music festivals, the arts, and outdoor recreation including hiking and biking trails. Without turning its back on its industrial heritage, Duluth rebranded itself as a genuine “battle-tested” city where entrepreneurs can grow their businesses while enjoying nature, culture, and a more relaxed lifestyle.

The commitment to enhance and market the quality of life in Duluth paid off, and both homegrown and relocating businesses expanded in the city. Maurice’s, a clothing retailer with hundreds of stores in the United States and Canada, built an 11-story headquarters building in downtown Duluth. Homegrown companies such as Loll Designs, maker of outdoor furniture, and Epicurean, maker of cutting boards and other wooden kitchen products, expanded there. While the local taconite mining industry continued to operate in the region, other industries including health care, education, and tourism as well as the above-mentioned companies grew and helped create a stronger and more diversified local economy. The city has proven that it can handle diversity and emerge on the other side even stronger.

Duluth is a great example of a forward-thinking “can-do” community that rebooted its economy and followed the roadmap to prosperity. It also illustrates the interconnection between the community components of quality of life and the economy. In this case, the economic recovery was stimulated by the city’s proactive strategy of investing in the arts, recreation, and other amenities, creating a new image or brand as a great place to live and build a business.

Sources:

“Turnaround Towns”. 2021. Carnegie UK Trust. www.carnegieuktrust.org.uk/project/turnaround-towns/

“Innovative Duluth | Twin Cities Business”. 2021. Twin Cities Business. https://tcbmag.com/innovative-duluth/

Performing arts can also serve as a catalyst for community and economic development. Music can attract visitors by the thousands to places such as New Orleans with its Jazz and Heritage Festival and North Carolina with its Merlefest. Visitors are also attracted to smaller towns to celebrate regional musical styles. Examples include Eunice, Louisiana with its Cajun music, and Mountain View, Arkansas with folk music. Both are now major tourist attractions. Performing arts also include theater, movies, and television. Colquitt, Georgia profiled in the Introduction, rebooted its local economy through innovation in performing arts with its Swamp Gravy production.

Some communities market themselves as a location for film or television productions. Many communities offer natural beauty, historic treasures, or built environments that provide backdrops for filming. Most states have a film office to promote their communities for filming, and it can be a big business in places such as Savannah, Georgia or Las Vegas, Nevada. But, it’s not only the larger places that can benefit. Dyersville, Iowa, where Field of Dreams was filmed, has a population of only 3,500, but the filming created the basis for continued tourism. Thanks to the smart strategy of the local Chamber of Commerce to buy merchandising rights to the movie, Field of Dreams made decades ago keeps tourist dollars flowing to Dyersville businesses. Likewise, Bozeman, Montana is widely known as the site for the film, A River Runs Through It. The town attracts tourists because of the movie and the related industry of sport fishing.

Building Prosperity With Community Enterprises

Not all places have natural beauty or tourism potential like the examples above, but what every place does have is the ability to consider community-owned enterprises as an option. These types of enterprises touch on many of the prosperous community components, including the social, quality-of-life, and economy components by encouraging members of the community to work together for economic progress. Community-owned businesses are just what they sound like: investors (usually residents) pool together resources to buy or build an enterprise that is needed or desired. This approach can be taken in response to the closing of a grocery store, restaurant, retail store, or even a local pub (England has quite a few pubs that are community-owned).

Community-owned enterprises often arise when there are no other options to keep essential services or to encourage the kind of development a community prefers. Several places in Montana and Wyoming have community-owned stores because there can be large distances between towns and no easy way to commute for shopping elsewhere. Some places are turning to community enterprises to address situations detrimental to public health and well-being, such as the lack of access to fresh food sources. For example, in St. Paul, Kansas the local government now owns and operates the community’s grocery store.14

Community-owned businesses are growing in popularity, and they are a new twist to an old institution (cooperatives) that can run the gamut from agriculture to buyer membership groups. They can also be formed for industrial production. Such is the case in the region of Emilia-Romagna in Italy where 30 percent of the gross regional product emanates from cooperatives. In fact, Emilia-Romagna has the largest concentration of cooperatives in the world. The Basque region in Spain is home to the largest single cooperative in the world, the Mondragon Corporation, a worker-owned enterprise. The cooperative movement is coming full circle. Cooperatives were once very popular in the earlier part of the 20th century, and now they are returning, creating locally focused enterprises to help build prosperous communities. Host communities often tout the virtues of cooperatives as ways to keep revenue, investments, and quality jobs in the local economy. Think creatively! If an opportunity exists in your community, a community-owned enterprise may be a viable option.

Historic Attractions as a Community Development Strategy

Many places have a rich and varied array of historic structures. Sometimes, these structures are at risk of being lost while at the same time there may be unmet demand for housing or other needs in the community. Why not think out of the box and consider establishing a community trust for acquiring suitable historic properties to rehab as affordable housing or even for use as public spaces? While community trusts often take the form of organizations for conservation of natural areas or preservation of farmlands, there is growing interest in establishing trusts for acquiring historic structures. This is a situation where collaboration and partnership building may be needed to acquire funds for acquisition. At the same time, housing is the one of the largest uses of land in most cities and towns so there could be significant potential to increase the supply, opportunity, and affordability of housing. Perhaps you are aware of renovations of historic houses or buildings in your community that helped spur nearby improvements. Renovated historic structures can serve as a catalyst and inspire more development projects. Even a few renovated houses on a street can change things rapidly; community developers call this the “window box effect.”

We are connected to our built environments deeply and improving historic assets so that community members can see progress helps further develop that ever important “sense of place.” We should never underestimate its importance. Sense of place is sometimes hard to define, but we know it when we experience it. Think of a charming downtown, seaside village, or iconic New England town that you’ve visited. Chances are it was graced by historical buildings. We normally don’t describe our communities in terms of ubiquitous fast food joints or strip malls even though they serve important functions. Instead, we tend to describe them in terms of their unique features including historic homes and structures such as a courthouse of Indiana limestone or a railroad hotel from a bygone era. Your community may even have a theater built long ago in need of restoration. Renovating old theaters or similar structures can serve as a catalyst for bringing together people to focus on their community. Why is this? Because old theaters back in their day were places to gather and experience a sense of community.

There are many places where historic preservation efforts stimulated development and attracted other investments into the community. Examples include Cape May, New Jersey’s Victorian seaside resort, and Eureka Springs, Arkansas’ Victorian village in the Ozark Mountains. Historic preservation can serve a vital role in community development, cutting across basic needs (infrastructure and housing), social needs (shared emotional connection), quality-of-life enhancements (arts and entertainment), and the economy from an increase in tourism. For an example of the broad impact historic preservation can have on a community, check out the story behind the renovation of a long defunct textile mill into the Mass MoCa center in North Adams, Massachusetts and the benefits accruing to the community and region.15

The Rebirth of a GEM: A Personal Reflection

Long before big screen TVs with video streaming and home surround sound systems came into vogue, there was a time when movie theaters were a social focal point for many small towns across America. Families attended theaters to be entertained and see places around the world they had only dreamt about. As a child growing up in Newnan, Georgia, 25 cents would buy me a Saturday morning of western and sci-fi adventure with my friends at the Alamo Theater. For another quarter or two, I could eat my fill of popcorn and candy.

When I was a teenager, my family moved to Calhoun, Georgia, and the Martin Theater became my new Alamo. James Bond and Rosemary’s Baby replaced cowboys and radioactive aliens but going to the movies (maybe even with a date!) was still a social event. Like many rural communities, Calhoun’s downtown lost its vibrancy to a neon strip of new discount stores and fast food restaurants just outside of town. The Martin Theater [previously known as the GEM theater (Figure 3.4) founded in 1927 as Calhoun’s only arts and movie venue] left downtown and built a new triple screen cinema where its customers were now shopping and dining.

With philanthropic help from a local family, a group of citizens formed a nonprofit corporation to save a piece of Calhoun’s history and restore the GEM to its former glory and role in the community. With money raised from public and private contributors, the renovated GEM Theater reopened in 2011, once again providing the residents of Calhoun and Gordon County with an opportunity to get together downtown for dinner and a show, and perhaps some shared memories of cinematic days gone by. From the GEM’s website:

The GEM features the best of both the past and present, as its appearance takes you back to 1939 and its amenities provide a state-of-the-art theater experience. The original GEM is best remembered as a movie theater, but the renovated 461-seat GEM showcases a variety of entertainment including concerts, plays, and movies ... After more than 70 years, the GEM has finally come full circle to entertain the citizens of Calhoun in all its original beauty and elegance …. Most importantly, the GEM is the community’s theater. It is the ‘gem’ in Calhoun’s crown.

Source: https://calhoungemtheatre.org/about/

—Robert Pittman

Historic preservation and creating a sense of community can also make a town more attractive to remote workers and companies in the new geography of work described in Chapter 2. This is just one example of community and economic development opportunities in the post pandemic new normal.

Well-Being and Sustainability

As mentioned earlier, measuring and tracking change is necessary to assess how a community is progressing, and what strategies and actions are working better than others. More specifically, communities should focus on measuring the community components and factors they have set as top priorities. However, some desired attributes and goals for a community cut across the four main components in our model of community prosperity. For example, health care was classified in Chapter 2 as a basic need without specifying its extent or quality because that is normally a function of community size. You wouldn’t expect a world-class cardiac care facility in a small town, but you would expect (or hope for) primary health services such as emergency treatment or hospitalization for common illnesses. In larger communities, you could expect secondary care from specialists. In even larger metro areas, you would expect tertiary care, such as heart bypass surgery, or even services such as experimental treatments that are classified as quaternary care.

However, some communities might want to set the bar higher for health care because of an older or vulnerable population, or simply because it is a community priority for all residents. The National Rural Health Association has given top ratings to 20 rural hospitals in places such as Brookings, South Dakota; Monroe, Wisconsin; and Pratt, Kansas.16 Going above the norm and achieving higher standards for services such as health care or education usually requires special efforts including the development and utilization of stronger ties among the four prosperous community components. Outstanding health care facilities don’t usually just spring from a community’s desire to provide basic services. Involvement and commitment to the community (social needs) and strong financial resources (economy) also play a role in most cases.

The concept of well-being is getting increasing attention in the field of community development. Dictionary.com defines well-being as “a good or satisfactory condition of existence; a state characterized by health, happiness, and prosperity.” This is consistent with our definition of community prosperity in Chapter 2 based on the four components of basic needs, quality of life, social needs, and the economy. However, the concept of well-being cuts across these four components and offers an even higher-order meaning of community prosperity.

In practice, most definitions of well-being in a community development context focus on the physical and emotional health of residents; some also include other things such as how well people meet their social needs, including interacting with each other in community decision-making processes. Various surveys and reports indicate that social bonding is a very important factor influencing well-being. Hence, there can be synergy here: community involvement by itself can improve community well-being, but it can also contribute to better community services such as health care. Whether measured by specific indicators or overall assessments, “being well” has taken on even more significance in the pandemic era.

Communities can and should have their own definitions of well-being depending on their priorities. For example, Lafayette, Indiana created their “Good to Great” plan in 2012 focusing on quality-of-life dimensions that influence their definition of community well-being. Since then, they have developed more biking trails and encouraged healthier, local food choices. Each year the community gathers data on quality of life to help focus efforts and revise them as needed.17 Places such as Lafayette that include measures of well-being in their planning and development activities will be more in tune with how their community is progressing on the road to prosperity.

Well-being is very closely tied to community sustainability, which is often divided into social, economic, and environmental sustainability as noted in a publication from McGill University:

Sustainability means meeting our own needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. In addition to natural resources, we also need social and economic resources. Sustainability is not just environmentalism. Embedded in most definitions of sustainability, we also find concerns for social equity and economic development. Without sustainability, the well-being of future generations is compromised.18

The prosperous community components provide a useful framework for understanding and implementing sustainable policies. Numerous surveys such as those cited in Chapter 2 show that community residents rank environmental safety as a very high priority. Places not providing the basic needs of clean air and water are not prosperous-ready. Contrary to the beliefs of many people, studies have shown that a strong economy can actually contribute to sustainability by making people less likely to sacrifice tomorrow’s resources for today’s economic growth.19

Realizing the importance of sustainability to community prosperity and well-being, many communities are beginning to incorporate sustainability into their community and economic development planning. Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Burlington, Vermont, are taking this approach; the smaller town of Truckee Meadows, Nevada is taking a regional approach to sustainability. Attention to sustainability and well-being can encourage a community to focus on its needs and assets for attaining prosperity. Connecting well-being, sustainability and community development can yield positive outcomes.

The Bridge to Economic Development

Creating a prosperous community, like building a house, involves two phases: (1) laying the foundation of a “prosperous-ready” community and (2) building on that foundation with economic development to achieve prosperity. Without that solid foundation, economic development efforts will most likely yield disappointing results. We do not wish that result for your community, so we strongly encourage you to build the foundation of a prosperous-ready community that is attractive to businesses, entrepreneurs, tourists (if that is part of your vision and plan), and residents who want a high quality of life and social opportunities. Understanding and applying the principles and practices of good community development will start you on your journey to community prosperity and building a place where residents enjoy the things that matter the most to them.

Prosperous Community Toolbox

Read, Reflect, Share, and Act

Chapter 3 of Rebooting Local Economies is about what you need to do to create a path to a more prosperous community so that you can start responding to and creating opportunities of your own. Establishing a strong foundation is essential for making use of your current assets, as well as identifying ways to improve your current condition (whatever it may be), and seizing opportunities.

Chapter 3’s tools are designed to help you identify the assets and resources your community already has that can make it more prosperous, measure your community’s social capital, and gain feedback from your community to understand your current situation.

3.1 Map the assets in your community. Conduct an asset mapping exercise or survey to find assets that can make your community more prosperous. Sometimes these are apparent and sometimes they are hidden (for example, skill sets that may exist across a group of residents). Asset mapping affords a better understanding of the relationships and synergies among a community’s assets.

3.2 Gauge your community’s social capital. Learn the characteristics of successful communities and community builders through the chapter’s worksheets and use those guides to rate your community

3.3 Take the Civic Index. The National Civic League developed the Civic Index to help communities measure and develop skills and processes for evaluating and improving their civic infrastructures. This index can aid the community visioning process and planning and strengthen problem-solving capacity.20

3.4 Get feedback on your community. Ask colleagues, friends, or others who visit your community to comment on what they see, both positive and negative. This is just another way of gathering objective input for your strategic plan for community and economic development. Work to build on the positive while remedying the negative.

3.5 Start a community visioning process. This is a significant undertaking, but as discussed in Chapters 2 and 3, it is quite essential for designing your community’s roadmap to prosperity. Use your draft roadmap from Chapter 2 and the above tools in Chapter 3 as inputs to the visioning process. After you have completed the process, revisit the draft Roadmap to Prosperity in Chapter 2 and adjust as appropriate. Visit www.prosperousplaces.org/rebooteconomics_toolbox/ to download templates and guides for the Chapter 3 tools.

How to Become a Media Darling or the Case of Creating Opportunity

Figure 3.5 Laurel, MS

Who would have ever thought a town of 18,000 in the Piney Hills region of Mississippi would become a tourist destination? That’s exactly what has happened since the renovation show, Home Town, started airing on the HGTV network. It’s about more than renovating houses like so many other shows. It includes a healthy measure of community development; the couple hosting it declares that they want to help revitalize their home town of Laurel (Figure 3.5). In the five years since the show began, Laurel has seen noticeable change due to new businesses dedicated to making over numerous homes and historic buildings in the town.

Interest in living in Laurel has noticeably increased. People from California, Arizona, and many other states have moved to the town’s historic districts with oak-lined streets and bordered by a parks system designed by none other than Frederick Law Olmstead in the 1800s. Laurel, known as the City Beautiful, has long been noted for its charming downtown and historic structures, as well as the short train ride on the historic Crescent Line to New Orleans. The train station has been renovated to preserve its historic charm. In the past, streetcars traversed the city built around the timber industry.

What made the difference, or should we say who made the difference? Young millennials started renovating historic structures downtown for upper floor condominiums and flats, drawing in people to live downtown. This led to the establishment of the Main Street Program that spurred further interest in the historic downtown and adjacent neighborhood districts. New businesses moved in, helping create an environment of locally focused enterprise imparting a unique feel and strong sense of place.

When hosts Ben and Erin Napier returned to Laurel after college, they decided to invest their artistic and building knowledge into renovating properties. When postings on social media caught the attention of a production company, they were asked to create a pilot, and the rest is history. Laurel became a sensation overnight, and while not every community will be lucky enough to have a television show produced in their town, the success speaks to how prepared the community was when opportunity came knocking. Laurel’s success also illustrates the mindset of creating opportunity—making things happen by building on the assets in a community. All places have them, but sometimes they are not evident. In the case of Laurel, the historic buildings were sitting there, waiting for opportunity. Community members and leaders in Laurel had the mindset to take advantage of the town’s assets and were ready to act when opportunity came. Being ready to take advantage of opportunity is an essential principle of community development; it prepares the community for positive economic development outcomes.

1 “Principles of Good Practice—Community Development Society,” 2021. Comm-Dev.Org. www.comm-dev.org/about/principles-of-good-practice

2 “Professional Community & Economic Developer,” 2021. Cdcouncil.Com. www.cdcouncil.com/PCED.htm

3 R. Phillips and R.H. Pittman. 2015. An Introduction To Community Development, New York, NY: Routledge.

4 There are quite a few studies, books and other writings about changes in rural America. For example, look at resources from the U.S. Department of Agriculture or any of the Rural Regional Development Centers. If you’re in the mood for a story about this instead, see the essay “Community Development and Economic Development: What is the Relationship? “ by R. Phillips (2016) and Sharpe, Erin K, Heather Mair, and Felice Yuen. n.d. Community Development.

5 Green and Haines. 2007. Asset Building and Community Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

6 A. Haines. 2015. “Asset-Based Community Development,” In Introduction to Community Development, eds. R. Phillips, and R. Pittman. 2nd ed., 45–56. London: Routledge.

7 P. Mattiessich. 2015. “Social Capital and Community Building,” In Introduction to Community Development, eds. R. Phillips, and R. Pittman. 2nd ed., 57–73. London: Routledge.

8 R. Phillips, and R. Pittman. 2015. “A Framework for Community and Economic Development,” In Introduction to Community Development, 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

9 U. Kjaer. 2013. “Local Political Leadership: The Art of Circulating Political Capital,” Local Government Studies 39, no. 2, pp. 253–272. doi:10.1080/03003 930.2012.751022

10 P. Mattiessich. 2015. “Social Capital and Community Building,” In Introduction to Community Development, R. Phillips and R. Pittman. 2nd ed, 57–73. London: Routledge.

11 R. Phillips and R. Pittman. 2015. “A Framework for Community and Economic Development,” In Introduction to Community Development, 2nd ed, 9. London: Routledge.

12 Programs, Our, FIRST League, FIRST Challenge, FIRST Competition, FIRST Fair, GIRLS’ GEN, and Summer Opportunities Alumni et al. 2021. “ORTOP,” ORTOP, https://ortop.org/

13 M. McGrath. 2015. “Community Visioning and Strategic Planning,” In Introduction to Community Development, eds. R. Phillips and R. Pittman, 2nd ed., 125–126. London: Routledge.

14 N. Walzer. 2021. Community Owned Businesses, 1st ed. Routledge.

15 Tickets, Get, Plan Visit, FAQ Info, Courtesy Code, More Museum, Sound Art, and LeWitt S. et al. 2021. “MASS Moca,” MASS Moca | Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, https://massmoca.org

16 “Top 20 Rural Community Hospitals—NRHA,” 2021. Ruralhealthweb. Org, www.ruralhealthweb.org/about-nrha/rural-health-awards/top-20-rural-community-hospitals

17 “Quality of Life—Greater Lafayette commerce,” 2021. Greater Lafayette Commerce, www.greaterlafayettecommerce.com/quality-of-life/

18 2021. Mcgill.Ca, www.mcgill.ca/sustainability/files/sustainability/what-issustainability.pdf

19 “Why Economic Growth Is Good for the Environment,” 2021. PERC, www.perc.org/2004/07/01/why-economic-growth-is-good-for-the-environment/

20 “Civic Index- 4th Edition,” 2021. National Civic League, www.nationalcivicleague.org/resources/civicindex