As we’ve seen during our exploration of its features so far, the a6600 is superbly equipped for taking still photographs of very high quality in a wide variety of shooting environments. But this camera’s superior level of performance is not limited to stills. It’s highly capable in the movie-making arena as well. It can shoot Full HD (high-definition) and 4K (ultra-high-definition) clips. Sony has also provided overrides for controlling all important aspects of a video clip.

So, even though you may have bought your camera primarily for shooting stationary scenes, you acquired a device that’s also great for recording high-quality video clips. Whether you’re looking to record informal clips of the family on vacation, the latest viral video for YouTube, or a set of scenes that will be painstakingly crafted into a cinematic masterpiece using editing software, the a6600 will perform admirably.

This camera can shoot HD video at 1920 × 1080 resolution using Sony’s AVCHD encoding. It also can capture HD video in the newer XAVC S format, and adds the ability to capture superior 4K video internally using XAVC S 4K. The camera also uses something called Picture Profiles to tailor color, saturation, sharpness, and some video-centric attributes. You can visualize Picture Profiles as Creative Styles for video. This chapter will show you the fundamentals of shooting video; in the next chapter, you’ll learn about some of your camera’s more advanced features, including the XAVC S format in HD and 4K options.

This chapter and the next deal with conventional video; S&Q (slow- and quick-motion video) settings were explained in Chapter 4.

Some Fundamentals

Recording a video with the a6600 is extraordinarily easy to accomplish—just press the black button with the red dot located at the upper right of the camera’s back to start. Sony has placed it there to minimize the chance that you’ll start recording a movie accidentally. That’s because video can be captured in any exposure mode; there’s no need to activate a special Movie mode. After you press the button, the camera will confirm that it’s recording with a red REC and numerals showing the elapsed time in the EVF and LCD monitor. Press the button again when you want to stop recording. (You can also define a different button to activate/deactivate video, such as the C1 key, using the Custom Keys options described in Chapter 4.)

Before you start, though, there are some settings to prepare the camera to record the scene the way you want it to. Setting up the camera for recording video can be a bit tricky, because it’s not immediately obvious, either from the camera’s menus or from Sony’s manuals, which settings apply to video recording and which do not. I will unravel that mystery for you, and throw in a few other tips to help improve your movies.

I’ll show you how to optimize your settings before you start shooting video, but here are some considerations to be aware of as you get started. Many of these points will be covered in more detail later in this chapter:

- Use the right card. Because movie capture, is, basically, full-time “continuous” shooting, you’ll need to use a memory card with sufficient capacity and a fast enough write speed to handle the streams of video you’ll be shooting.

- For AVCH format. Sony recommends using an SD, SDHC, or SDXC memory card with Class 4 or UHS Speed Class U1, or faster. You can also use Sony Memory Sticks of the Pro Duo II, PRO-HG, or Micro II variety. With slow cards, your recording may stop after a minute or two until the card is able to offload the captured video from your camera. In practice, virtually all memory cards sold today are Class 10, but you may still have some older cards in your kit.

- For XAVC S format. Sony recommends SDXC memory cards 64GB or larger, and Speed Class 10 or UHS U1 or faster write speeds. If you elect to use the 30p or 24p options with 100M bit transfer rates, you must have a UHS-1-U3-compatible memory card inserted. (I’ll explain more about bit transfer rates later in Chapter 11.)

- Avoid extraneous noise. Try not to make too much noise when changing camera controls or when using a conventional zoom lens’s mechanical zooming ring. The sound made by a mechanical zoom ring rotating will be picked up and it will be audible when you play a movie. (Lenses with power zoom are virtually silent, however.) And don’t make comments that you will not want to hear on the audio track.

- Minimize zooming. While it’s great to be able to use the zoom for filling the frame with a distant subject (especially the power zoom on lenses equipped with that feature), think twice before zooming. The sound made by a mechanical zoom ring rotating will be picked up and it will be audible when you play a movie. (As I noted, lenses with power zoom are virtually silent.) As well, remember that any more than the occasional minor zoom will be very distracting to friends who watch your videos.

- Use a fully charged battery. A fresh battery will allow about one hour of filming at normal (non-winter) temperatures, but that can be shorter if there are many focus adjustments. Individual clips can be no longer than 29 minutes, however.

- Keep it cool. Video quality can suffer terribly when the imaging sensor gets hot so keep the camera in a cool place. When shooting on hot days especially, the sensor can get hot more quickly than usual; when there’s a risk of overheating, the camera will stop recording and it will shut down about five seconds later. Give it time to cool down before using it again. And remember that when you record a couple of very long clips in a series, the sensor will start to get warm; it’s better to wait a few minutes to let it cool before starting to record another clip. This limitation generally won’t affect serious movie makers, who tend to shoot a series of short scenes that are assembled into a finished movie with an editor. But if you plan to set up your camera and shoot your kid’s school pageant non-stop for an hour, you’re out of luck.

- Press the Movie button. You don’t have to hold it down. Press it again when you’re done to stop recording. It’s recessed so you will not press it inadvertently.

Preparing to Shoot Video

First, here’s what I recommend you do to prepare for a basic recording session. More advanced detail settings will be addressed later:

- Choose your file format. Go to the File Format entry in the Camera Settings II-01 menu (as discussed in Chapter 3) and select the file format for your movies. (The mode dial must be set to Movie mode to access this entry.) You can set it to AVCHD, XAVC S HD, or, with the a6600, XAVC S 4K. File formats determine the transfer rate (roughly equivalent to JPEG compression), which, with resolution, determines the quality of your video. You’ll learn more about these formats later.

- Choose record setting. Also, in the Camera Settings II-01 menu, you’ll find the Record Setting item, which allows you to choose the size, frame rate, and image quality for your movies. Tables 10.1 to 10.4 later in this chapter spell out your choices.

Which of the many options should you choose? It depends in part on your needs. If your plan is to primarily shoot videos that you’ll show to friends and family on an HDTV set, choose AVCHD. For more professional productions, you’ll want to select XAVC S HD or XAVC S K. I’ll explain the differences later.

- Activate proxy recording (optional). If you are shooting an XAVC S or AVCHD movie, you can elect to record a lower 9 Mb/sec. bit-rate (reduced quality) Standard HD (1280 × 720) movie simultaneously, giving you a video optimized for viewing on a smart device or website. Use the Proxy Recording entry in the Camera Settings II-01 menu. You’ll definitely want to use a larger memory card when working with this option. When you review your images, the proxy video isn’t displayed, viewable, or editable in the camera; the “main” movie will have a Px indicator overlaid on its icon to show you that the clip is paired with a proxy counterpart. Deleting or protecting the main clip deletes/protects the proxy at the same time.

- Preview the movie’s aspect ratio for stills. In the Aspect Ratio entry of the Camera Settings I-01 menu, the proportions default to 3:2, but you can change that to 4:3, 16:9, or 1:1. The setting in this item won’t affect your video recording. Setting the aspect ratio options will merely cause the camera to display the preview of the scene when you are shooting stills, before you start movie recording, in the format that will be used for the video clip. This gives you a better feel for what will be included in the frame after you press the record button.

- Turn on autofocus. Make sure autofocus is turned on through the Focus Mode entry of the Camera Settings I-05 menu. You also have the option of using manual focus, or even Direct Manual Focus, with focus peaking. I find that manual focus is fine for situations such as a stage play where the actors will usually be at roughly the same distance to your position during the entire performance, and for more professional productions where precise focus is a must, or when changing focus during a shot (focus pulling) is used creatively. In other cases, however, you’ll probably want to rely on the camera’s effective full-time continuous autofocus ability while recording a video clip.

- Try Flexible Spot AF Area. As in still image making, you can use the Flexible Spot AF Area (discussed in Chapter 8) while recording a video clip. This feature is most suitable for a static scene you’ll record with the camera on a tripod, where an important small subject is off-center and will remain in the same location. By placing the AF Area exactly on that part of the scene, you’ll be sure that the focus will remain on the most important part of the scene during the entire recording. (In truth, you could use manual focus for the same purpose.)

If you decide to try this, compose the scene as desired before pressing the record button. Set the Focus Area to Flexible Spot in the Camera Settings I-05 menu. Brackets will appear on the screen, indicating the current location of the active focus detection point. Move the brackets with the directional buttons so they cover the primary subject and press the center button to confirm. You can now begin recording the video, confident that the focus will always be on your primary subject (assuming it does not move while you’re recording).

- Set useful functions. Before you start recording, you can set a desired ISO, white balance, Creative Style, Picture Profiles (explained in the next chapter), a Picture Effect (for special effects), any of the three metering modes, and the level of exposure compensation. You can also set an override in the Creative Style for a specific level of sharpness, contrast, and saturation, if desired, or use a Picture Profile for more advanced parameters. The DRO feature will not be available, however. You’ll recall that these functions are not available in fully automatic modes; if you set them while using another mode and then switch to a fully automatic mode for recording the video, the camera will revert back to the defaults.

- Decide on a shooting mode. You can choose an exposure mode (P, S, A, or M) for your movies, either using a menu entry or by rotating the mode dial.

The P mode works well, allowing the camera to set the aperture/shutter speed and giving you access to the other features discussed above. Program shift (to other aperture/shutter speed combinations) can be used before you start recording, but it will not be available during actual recording.

You might prefer to use Aperture Priority (A) mode for full control over the specific aperture; in that case, you can preset a desired aperture and you can also change it anytime while recording. Be careful however, especially if you have set a specific ISO level. If you switch to a very small aperture while recording in low light, your movie clip may darken; this is particularly likely if you’re using a low ISO level. And if you switch to a very wide aperture on a sunny day, especially if using a high ISO, your video will become too bright. Of course, you can see the change in brightness in the live view display before recording a movie and while you’re recording.

Switch to S mode if you want control over the shutter speed; this is a more advanced technique in Movie mode. You can preset a shutter speed and you can change it while recording. Again, be careful as to your settings to avoid a very dark or overly bright video, especially if you have set a specific ISO level. The live view display before and during recording will help to guide you. I don’t recommend using the Manual (M) mode initially but you might want to experiment with it later.

- Press the record button. You don’t have to hold it down. Press it to start recording and press it again when you’re done. Shoot a short test clip and view it to make sure that the settings you made are producing the overall effect you want. If not, change some settings (White Balance or Creative Style or Exposure Compensation, for example) and try again.

Steps During Movie Making

Once you have set up the camera for your video session and pressed the Movie button, you have done most of the technical work that’s required of you for basic movie clips. Now your task is to use your skills at composition, lighting, scene selection, and, perhaps, directing actors, to make a compelling video production.

- Zoom, autofocus, and autoexposure all work. If you’re new to the world of high-quality still cameras that also take video, you may just take it for granted that functions such as autofocus continue to work normally when you switch from stills to video. But until recently, most such cameras performed weakly in their video modes; they would lock their exposure and focus at the beginning of the scene, and you could not zoom while shooting the video. The a6600 has no such handicaps, and, in fact, it is especially capable in these areas.

Indeed, this camera allows you to choose any exposure mode, including Manual exposure, Auto ISO, shutter speed, and aperture. You can change settings while shooting, and lock exposure with the AEL button.

Autoexposure works very well, modifying the exposure as the scene brightness changes; the method used depends on the metering mode that you’re using. You can zoom to your heart’s content (though I recommend that you zoom sparingly). Best of all, AF-C autofocus works like a charm; the camera can track moving subjects and quickly snap them back into sharp focus with speedy continuous AF. Manual focus is also available, with focus peaking to help you zero in on a focus plane. Don’t limit yourself based on the weaknesses of past cameras; the a6600 opens up new horizons of video freedom.

- Exposure compensation works while filming. I found this feature to be quite remarkable. Although the autoexposure system works very well (especially with Multi metering) to vary the aperture when the ambient lighting changes, you can certainly dial in exposure compensation when you need to do so or want to do so for a certain effect. You could even use this function as a limited kind of “fade to black” in the camera, though you probably won’t be able to fade quite all the way to black.

If the preview display suggests that your movie will be dark (underexposed) and if it does not get brighter after you set plus compensation, there’s another problem: the camera cannot provide a good exposure for the movie at the ISO that you have set (as discussed earlier). Switch to a higher ISO level until the brightness is as desired or switch to ISO Auto to enable the camera to set a higher ISO level to prevent the “underexposure.”

- Use AE Lock instead. Occasionally, you may find that you start having an exposure problem during recording; this might happen when pointing the lens toward a light-tone area that causes the camera to begin underexposing. While plus compensation will allow you to increase brightness, it’s preferable to use the defined AE Lock button (either the physical AEL button or one you specify using Custom Keys in the Setup menu) to maintain a pleasing exposure during the entire video clip.

Let’s say you’re filming entertainers against grass and foliage, but you’re moving the camera and will soon be filming a second group against a white sky. As soon as you do so, the backlighting will cause the video to get darker. Don’t let that happen. Before pointing the lens toward the backlit area, press AEL and keep it depressed. This will prevent the exposure from changing as you point the lens toward the backlit part of the scene. This is preferable to waiting until an underexposure problem starts and then setting plus exposure compensation that suddenly makes the video brighter.

- Don’t be a flash in the pan. With HD video, there is a possibility of introducing artifacts or distortion if you pan too quickly. (This effect is called rolling shutter distortion or the “Jell-O effect.”) That is, because of the way the lines of video are displayed in sequence, if the camera moves too quickly in a sideways motion, some of the lines may not show up on the screen quickly enough to catch up to the rest of the picture. As a result, objects in your video can become somewhat distorted or you may experience a jiggling effect and/or loss of detail. So, if at all possible, make your pans smooth and steady, and slow them down to a comfortable pace.

Choosing a File Format

Visit the File Format entry in the Camera Settings II-01 menu (as discussed in Chapter 4) and select the file format for your movies. The a6600 offers full HD (high-definition) video recording in the AVCHD format. Advanced video shooters can also choose from the XAVC S 4K or XAVC S HD formats, which support faster recording speeds for improved quality.

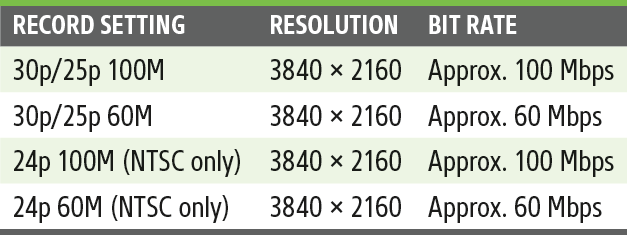

By default, movies are recorded in XAVC S HD, but this menu item allows you to switch to XAVC S 4K AVCHD. In any case, you’ll need a fast memory card of at least 64GB capacity to support the higher frame rates possible with these pro formats. The XAVC S 4K format is especially demanding because of its ultra-high 3840 × 2160–pixel resolution (roughly four times that of full HD).

AVCHD clips are limited to roughly 2GB in size; when your movie file reaches that limit, the a6600 will continue recording using a new file that it creates automatically. If you’re using an external recorder, video monitor, or other device using the a6600’s HDMI connection, the real-time image is not displayed on the camera’s LCD monitor as you shoot.

So your first choice will be should you be shooting standard/full high-definition movies, or ultra-high-definition (4K) video? If your memory card (which must be a 64GB or larger SDXC card to use the fastest bit rates) or external recorder, like the Atomos Shogun, can handle the data rates, 4K is alluring, even if your movies will never be viewed in anything other than 1080p format. All that extra detail is hard to resist.

In the discussions that follow, you’ll see reference to a “Super 35” format that is applied to many of the full HD formats. In practice, Super 35 is simply the area captured by an APS-C-format camera like the a6600, but cropped to the 16:9 proportions of SD/HD/UHD video, effectively 6000 × 3376 pixels. Sony says that when capturing 4K video at 24p/25p, each pixel is read directly from the full width of the sensor and then downscaled to the selected video resolution. (At 30p, a tighter 1.23X crop is used; and at 120/100p Full HD recordings use a 1.14X crop.)

The alternative is a process called pixel binning, which averages the data from several adjacent pixels, producing a lower-quality image. Directly capturing pixels produces an improved image, which should have reduced moiré effects, sharper detail with less noise, and a reduction of “rolling shutter” problems (described next).

Choosing a Record Setting

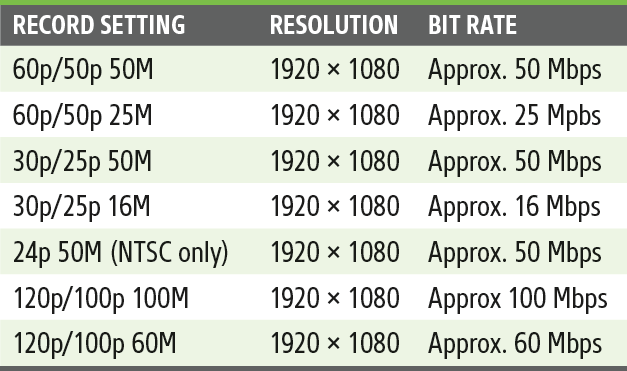

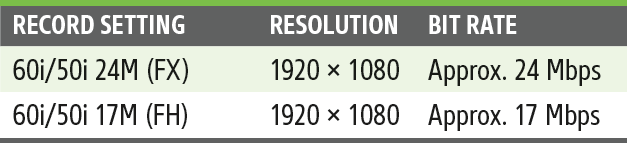

Once you’ve selected the File Format from among XAVC S 4K, XAVC S HD, AVCHD, or MP4, you can use the next entry in the Camera Settings II-01 menu to select your Record Setting. This entry allows you to choose the size, frame rate, and image quality for your movies, and the available options differ, depending on the file format you’ve specified. Tables 10.1 to 10.3 later in this section spell out your choices. Each of the tables lists the frame rates, whether progressive scanning or interlacing is used, and the bit transfer rate of the video information from the sensor to the memory card (or external video recorder).

How Video Is Captured

In truth, both videos and stills are captured in much the same way, but the technology used for the sensor can cause problems that are most evident when shooting movies. To understand why, it’s necessary to understand the difference between a rolling shutter and a global shutter, and how interlacing differs from progressive scan.

An image (still or video) captured by the sensor consists of rows and columns of pixels. With the a6600, there are 4,000 different rows, each row consisting of 6,000 individual pixels. A “rolling” shutter captures each row one after the other, so that, effectively, the pixels in the top row are captured at a different moment in time than those in the bottom row. This gap is very brief, and typically isn’t noticeable in still photographs. But with video this difference can manifest itself as anomalies such as wobble (or Jell-O effect when the camera is moving or vibrating), skew (which is a diagonal bending of an image due to wobble), smear (produced when part of the image, such as an automobile tire, is rotating), and other defects.

A “global” shutter, on the other hand, captures the entire image in one instant, eliminating these problems. Although your a6600 does have a rolling shutter, the high speed of its sensor (aided by the improved on-sensor copper wiring of this all-new 24M sensor) almost eliminates the rolling shutter effects.

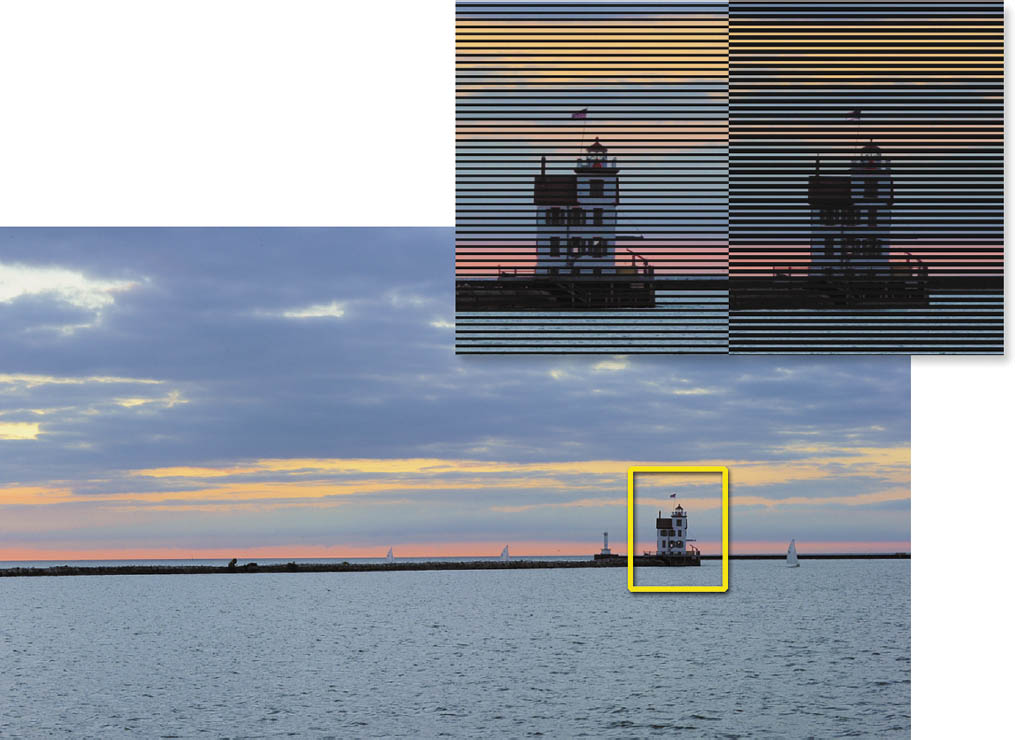

That leads us to progressive scanning versus interlacing. Line-by-line scanning during capture and playback can be done in one of two ways. With interlaced scanning, odd-numbered lines (lines 1, 3, 5, 7, and so forth) are captured with one pass, and then the even-numbered lines (2, 4, 6, 8, and so forth) are grabbed. With the 1080/60i format, roughly 60 pairs of odd/even line scans, or 60 fields are captured each second. (The actual number is 59.94 fields per second.) Interlaced scanning was developed for and works best with analog display systems such as older television sets. It was originally created as a way to reduce the amount of bandwidth required to transmit television pictures over the air. Modern LCD, LED, and plasma-based HDTV displays must de-interlace a 1080i image to display it. (See Figure 10.1.)

Figure 10.1 The inset shows how lines of the image alternate between odd and even in an interlaced video capture.

Newer devices work better with a second method, called progressive scanning or sequential scanning. Instead of two interlaced fields, the entire image is scanned as consecutive lines (lines 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth). This happens at a rate of 30 frames per second (not fields), or, more precisely, 29.97 frames per second. (All these numbers apply to the NTSC television system used in the United States, Canada, Japan, and some other countries; other places use systems like PAL, where the nominal scanning figures are 50/25 rather than 60/30.)

One problem with interlaced scanning appears when capturing video of moving subjects. Half of the image (one set of interlaced lines) will change to keep up with the movement of the subject while the other interlaced half retains the “old” image as it waits to be refreshed. Flicker or interline twitter results. That makes your progressive scan (p) options a better choice for action photography. Interlaced video frame rates are indicated with an (i) designation; for example, within the AVCHD choices, 60i 24M (FX) indicates interlaced video, while 60p 28M (PS) represents progressive scan video. (I’ll explain the 24M/28M part in the next section.)

Computer-editing software like Final Cut Pro can handle either type, and convert between them (although AVCHD, XAVC S 4K, and XAVC S HD may not be compatible with the other software you own). The choice between 24 fps and 60 fps (NTSC), or 25 fps and 50 fps (PAL) is determined by what you plan to do with your video. The short explanation is that, for technical reasons I won’t go into here, shooting at 24 fps (or 25 fps) gives your movie more of the so-called “cinematic” look that film would produce, excellent for showing fine detail. However, if your clip has moving subjects, or you pan the camera, 24 fps (or 25 fps) can produce a jerky effect called “judder.” The 60 fps (or 50 fps) option produces a home-video look that some feel is less desirable, but which is smoother and less jittery when displayed on an electronic monitor. I suggest you try both and use the frame rate that best suits your tastes and video-editing software.

You’ll note that when shooting XAVC S HD, you can select 120p (at 100Mbs transfer rates; NTSC only) or 120/100p (at 60Mbs transfer rate; both NTSC and PAL). These high frame rates—amounting to 120 and 100 frames per second—produce video that can be converted to play back at conventional speeds, either 30/25 fps (four times slower than recorded) or 24 fps (five times slower than recorded; NTSC only). The slow-motion video that results can be used for special effects, including clichés like two long-lost lovers running toward each other on a beach.

Bit Rates

Bit rates represent the speed of transfer from your camera to your memory card or external video recorder. The higher the bit rate, the more demands made on your media in storing that data quick enough to keep pace with the video capture. Higher average bit rates range from 6 Mbps (megabits per second) for 1280 × 720 (720p) MP4 movies, to as much as 28 Mbps maximum for AVCHD, 60p full-HD clips. When using XAVC formats, the demands are even higher: 50 Mbps with XAVC S HD and 60 to 100 Mbps with XAVC S 4K (with the a6600 only). Tables 10.1 to 10.3 show the frame rates, bit rates, and resolution of the various recording settings for video. Note that frame rates of 30/25, 60/50, and 120/100 represent NTSC/PAL systems, respectively.

Choosing Metering/Exposure Modes

You can use Multi, Center, or Spot metering when shooting movies. I recommend sticking with Multi metering, unless you have a special reason for, say, Spot metering, as I explained in Chapter 7. Next, you’ll want to select exposure mode, from among Program, Aperture Priority, Shutter Priority, or Manual. Rotate the mode dial to the Movie position and specify which of these modes is used for movies using the Movie/S&Q Motion entry or Exposure Mode entry in the Camera Settings II-01 menu page, as explained in Chapter 4. The mode you select will be used when the mode dial is in the Movie position. Of course, using the Movie position on the mode dial isn’t mandatory, as you can use any exposure mode for movie recording.

- Program mode. The P mode works well for movies, allowing the camera to set the aperture/shutter speed. Program shift (to other aperture/shutter speed combinations) can be used before you start recording, but it will not be available during actual recording.

- Aperture Priority. You might prefer to use Aperture Priority (A) mode for full control over the specific aperture; in that case, you can preset a desired aperture and you can also change it anytime while recording. However, remember that your shutter speed may change in Aperture Priority mode, and when shooting movies, it is often desirable to use a specific shutter speed (as I’ll explain in an upcoming section).

- Shutter Priority. Switch to S mode if you want control over the shutter speed; this is a more advanced technique in Movie mode. You can preset a shutter speed and you can change it while recording. Again, be careful as to your settings to avoid a very dark or overly bright video, especially if you have set a specific ISO level. The live view display before and during recording will help to guide you. I recommend Shutter Priority highly, especially for beginners.

- Manual Exposure. Manual exposure may be best when you want to maintain tight control over shutter speed and aperture, say, to maintain exposure as lighting conditions change, or to keep the same depth-of-field in a scene under changing conditions.

As you work, you’ll discover that the a6600’s Zebra feature in the Camera Setting II-06 (Display/Auto Review 1) menu, as explained in Chapter 4, can be a marvelous aid in monitoring your exposure. If you are using Shutter Priority, as I recommended, you’ll have the shutter speed fixed and, based on what you see in the viewfinder or LCD monitor and Zebra display feedback, adjust the aperture or ISO sensitivity to get the exposure you want. As I explained in Chapter 4, you can adjust the Zebra feature’s threshold setting, perhaps specifying 95% so that you’re alerted only when the brightest highlights start to clip (making the stripes less distracting) or use 85% so you’ll know when human skin starts to be overexposed. Zebra display may not work for you when using S-Log2/S-Log3 gamma settings (described later in this chapter), as those very low contrast renditions don’t lend themselves to that kind of monitoring.

Should you need to adjust exposure from what the camera recommends, exposure compensation works quite well while filming. Although the autoexposure system does a good job (especially with Multi metering) to vary the aperture when the ambient lighting changes, you can certainly dial in exposure compensation when you need to do so or want to do so for a certain effect. You could even use this function as a limited kind of “fade to black” in the camera, though, as I mentioned earlier, you probably won’t be able to fade quite all the way to black.

If the preview display (when Live View Display is set to Setting Effect On in the Camera Setting II-07 menu) suggests that your movie will be dark (underexposed) and if it does not get brighter after you set plus EV compensation, there’s another problem: the camera cannot provide a good exposure for the movie at the ISO that you have set (as discussed earlier). Switch to a higher ISO level until the brightness is as desired or switch to ISO Auto to enable the camera to set a higher ISO level to prevent the “underexposure.”

You can also “lock” exposure to keep the same exposure settings as lighting changes or you reframe your scene. Occasionally, you may find that you start having an exposure problem during recording; this might happen when pointing the lens toward a light-tone area that causes the camera to begin underexposing. While plus compensation will allow you to increase brightness, it’s preferable to use the defined AE Lock button (either the physical AEL button or one you specify using Custom Key (Movie) options in the Camera Settings II-08 menu) to maintain a pleasing exposure during the entire video clip.

Why would you need this feature? As I mentioned, let’s say you’re filming entertainers against grass and foliage, but you’re moving the camera and will soon be filming a second group against a white sky. As soon as you do so, the backlighting will cause the video to get darker. Don’t let that happen. Before pointing the lens toward the backlit area, press AEL and keep it depressed. This will prevent the exposure from changing as you point the lens toward the backlit part of the scene. This is preferable to waiting until an underexposure problem starts and then setting plus exposure compensation that suddenly makes the video brighter.

Stop That!

Both Manual Exposure and Shutter Priority modes allow you to explicitly choose a shutter speed. You might think that setting your camera to a faster shutter speed will help give you sharper video frames. But the choice of a shutter speed for movie making is a bit more complicated than that. As you might guess, in most cases it’s best to leave the shutter speed at 1/30th or 1/60th second and allow the overall exposure to be adjusted by varying the aperture and/or ISO sensitivity.

Remember that. Effectively, you’re better off working in Shutter Priority mode, so that the aperture or ISO settings are your only way of adjusting the exposure. A “slow” 1/30th or 1/60th second shutter speed doesn’t mean your movies will have the same amount of blur that a typical still photograph will have using those shutter speeds. We don’t normally stare at a video frame for longer than 1/30th or 1/24th second, so while the shakiness of the camera can be disruptive (and often corrected by your camera’s in-lens and in-body image stabilization), if there is a bit of blur in our subjects from movement, we tend not to notice. Each frame flashes by in the blink of an eye, so to speak, so a shutter speed of 1/30th or 1/60th second works a lot better in video than it does when shooting stills. Even shots with lots of movement, such as the frame shown in Figure 10.2, are often sufficiently sharp at 1/60th second.

Higher shutter speeds actually introduce problems of their own. If you shoot a video frame using a shutter speed of 1/250th second, the actual moment in time that’s captured represents only about 12 percent of the 1/30th second of elapsed time in that frame. Yet, when played back, that frame occupies the full 1/30th of a second, with 88 percent of that time filled by stretching the original image to fill it. The result is often a choppy/jumpy image, and one that may appear to be too sharp.

Figure 10.2 Movement adds interest to a video clip.

The reason for that is more social imprinting than scientific: we’ve all grown up accustomed to seeing the look of Hollywood productions that, by convention, were shot using a shutter speed that’s half the reciprocal of the frame rate (that is, 1/48th second for a 24 fps movie). Movie cameras use a rotary shutter (achieving that 1/48th second exposure by using a 180-degree shutter “angle”), but the effect on our visual expectations is the same. For the most “film-like” appearance, use 24 fps and 1/60th second shutter speed.

Faster shutter speeds do have some specialized uses for motion analysis, especially where individual frames are studied. The rest of the time, 1/30th or 1/60th of a second will suffice. If the reason you needed a higher shutter speed was to obtain the correct exposure, use a slower ISO setting, or a neutral-density filter to cut down on the amount of light passing through the lens. A good rule of thumb is to use 1/60th second or slower when shooting at 24 fps; 1/60th second or slower at 30 fps; and 1/125th second or slower at 60 fps.

In choosing between 30p and 60p, there are several considerations. The 30p frame rate allows you to use a reduced ISO setting for improved grain compared to 60p at a higher ISO value. That’s an advantage under low light. However, as I mentioned earlier, at 60p you can safely use a higher shutter speed of 1/125th second, which can produce smoother video of moving subjects. Video editors can transcode 60p video to give you 30p video (with files suitable for uploading to websites) as well as the 60i video you might need for DVD/Blu-Ray productions.

Choosing an Autofocus Mode

As I said in Chapter 8, you’ll generally want sharp focus in your image—somewhere—but exactly where and how focus is achieved can be an important part of your creative process. On the one hand, while shooting certain types of scenes—particularly action scenes—you’ll want the camera to automatically retain focus on your main subjects and keep them tightly in focus. Other times, you’ll want to use selective focus to emphasize a subject and de-emphasize the background, or “pull” focus to dramatically change the focus (so to speak) of the scene, say, refocusing to cause a blurry subject to suddenly come into sharp relief.

As with still photography, you have both manual focus and autofocus tools at your disposal, which allow you to specify when to focus and what to focus on. An important step before shooting is to ensure autofocus is turned on through the Focus Mode entry of the Camera Settings or Function menus. Only Continuous AF (AF-C) and Manual Focus (MF) can be used when shooting movies. Here are some points to consider.

- AF-C or MF. If the mode dial is in the Movie position, only AF-C and MF are available.

- Presto change-o. If the mode dial is not in the Movie position, and you have selected a focus mode other than AF-C or MF, when you begin shooting movies, the a6600 will automatically switch to AF-C.

- Lock focus. As video is captured, the a6600’s Continuous autofocus will refocus as you move the camera, or subjects in the frame change location. To lock focus, press the shutter release halfway, or use a key you’ve assigned that function. When you release the button, the camera will refocus. Ordinarily, it does an excellent job of not refocusing constantly, and changes focus only when the a6600 detects camera or subject movement.

- Manual focus. If you prefer manual focus, you’ll need to set it before commencing video capture. I find that manual focus is fine for situations such as a stage play where the actors will usually be at roughly the same distance to your position during the entire performance, and for more professional productions where precise focus is a must, or when changing focus during a shot (focus pulling) is used creatively. In other cases, however, you’ll probably want to rely on the camera’s effective full-time continuous autofocus ability while recording a video clip.

- Focus area modes. You can use all focus area modes, as described in Chapter 8, except for Tracking AF. Center Lock-On, however, can be used. Try Flexible Spot AF. As in still image making, you can use the Flexible Spot AF Area (also discussed in Chapter 8) while recording a video clip. This feature is most suitable for a static scene you’ll record with the camera on a tripod, where an important small subject is off-center and will remain in the same location.

By placing the Focus Area exactly on that part of the scene, you’ll be sure that the focus will remain on the most important part of the scene during the entire recording. (In truth, you could use manual focus for the same purpose.) If you decide to try this, compose the scene as desired before pressing the record button. Set the Focus Area to Flexible Spot in the Camera Settings I-05 menu. When you press the center button (or designated Focus Standard button), locator brackets will appear on the screen, indicating the current location of the active focus detection point. Move the bracket with the directional buttons so they cover the primary subject and press OK (the center button) to confirm. You can now begin recording the video, confident that the focus will always be on your primary subject (assuming it does not move while you’re recording).

- AF Drive Speed/Tracking Sensitivity. As I explained in Chapter 4, using this pair of entries in the Camera Settings II-02 menu, you can specify how quickly the a6600 focuses in movie mode, and the responsiveness of the autofocus system to moving subjects. Because video captures your subject in continuous sequences, changes in focus during a shot are visible when the clip is played back, so the speed and response of the AF system is an important aspect to consider. Fast focusing and response works well with most subjects, but may induce vertigo when the camera constantly adjusts focus on fast, herky-jerky motion.

Tips for Movie Making

I’m going to close out this introductory movie chapter with a general discussion of movie-making concepts that you need to understand as you move toward more polished video production. In the chapter that follows, I’ll explain some of the a6600’s features that allow you to produce more sophisticated movies. Here are some basic tips:

- Keep things stable and on the level. Camera shake’s enough of a problem with still photography, but it becomes even more of a nuisance when you’re shooting video. While the a6600’s in-body five-axis stabilization and stabilizer found in lenses with the OSS designation can help minimize this, neither can work miracles. Placing your camera on a tripod will work much better than trying to hand-hold it while shooting. One bit of really good news is that compared to pro dSLRs, the a6600 can work very effectively on a lighter tripod, due to the camera’s light weight. On windy days however, the extra mass of a heavy tripod is still valuable.

- Use a shooting script. A shooting script is nothing more than a coordinated plan that covers both audio and video and provides order and structure for your video. A detailed script will cover what types of shots you’re going after, what dialogue you’re going to use, audio effects, transitions, and graphics.

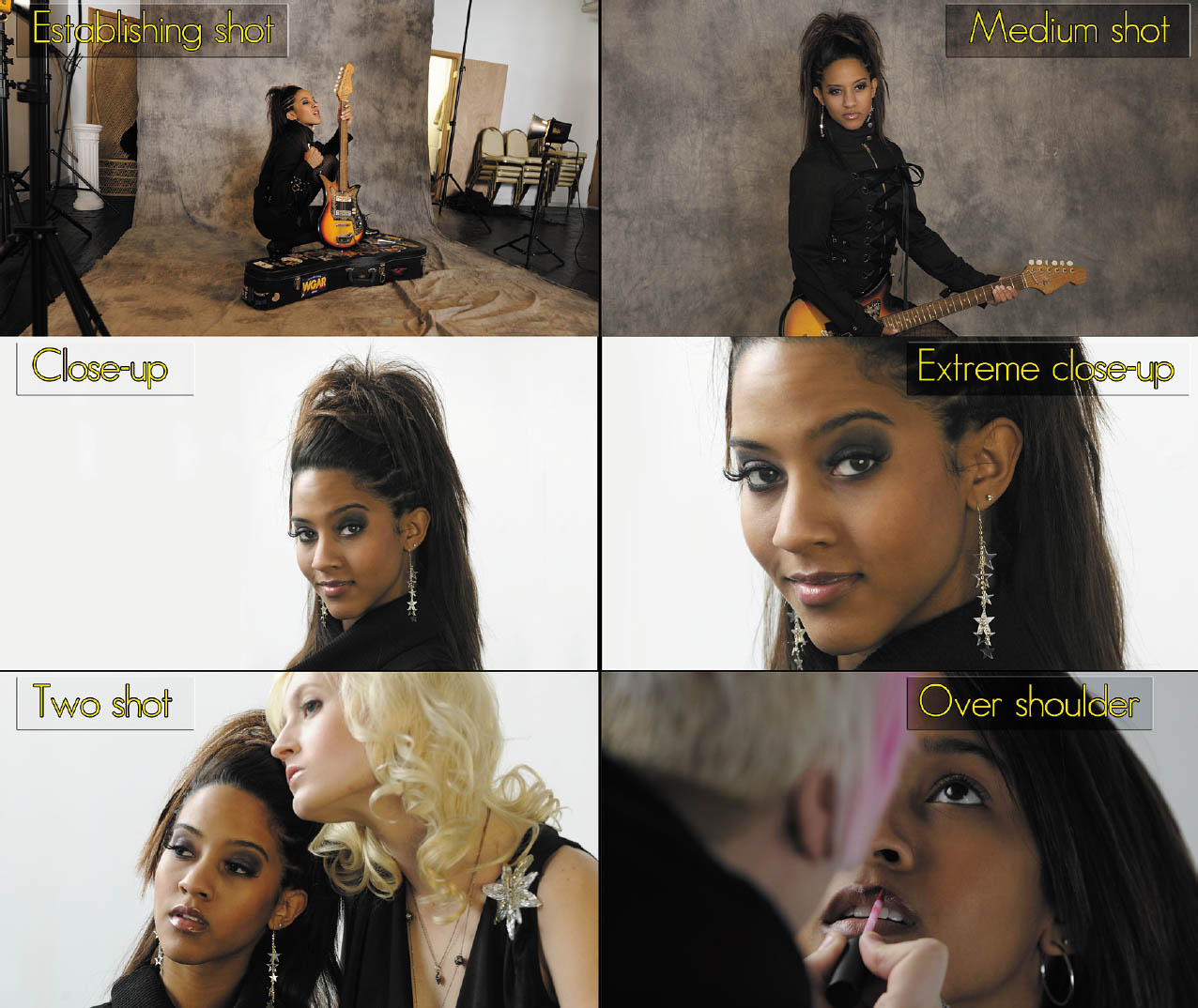

- Plan with storyboards. A storyboard is a series of panels providing visuals of what each scene should look like. While the ones produced by Hollywood are generally of very high quality, there’s nothing that says drawing skills are important for this step. Stick figures work just fine if that’s the best you can do. The storyboard just helps you visualize locations, placement of actors/actresses, props, and furniture, and also helps everyone involved get an idea of what you’re trying to show. It also helps show how you want to frame or compose a shot. You can even shoot a series of still photos and transform them into a “storyboard” if you want, such as in Figure 10.3. Today’s audience is used to fast-paced, short-scene storytelling. In order to produce interesting video for such viewers, it’s important to view video storytelling as a kind of shorthand code for the more leisurely efforts print media offers. Audio and video should always be advancing the story. While it’s okay to let the camera linger from time to time, it should only be for a compelling reason and only briefly.

It only takes a second or two for an establishing shot to impart the necessary information. For example, many of the scenes for a video documenting a model being photographed in a rock ‘n’ roll music setting might be close-ups and talking heads, but an establishing shot showing the studio where the video was captured helps set the scene.

Figure 10.3 A storyboard is a series of simple sketches or photos to help visualize a segment of video.

- Provide variety. Provide variety too. Change camera angles and perspectives often and never leave a static scene on the screen for a long period of time. (You can record a static scene for a reasonably long period and then edit in other shots that cut away and back to the longer scene with close-ups that show each person talking.)

- When editing, keep transitions basic! I can’t stress this one enough. Watch a television program or movie. The action “jumps” from one scene or person to the next. Fancy transitions that involve exotic “wipes,” dissolves, or cross fades take too long for the average viewer and make your video ponderous.

Composition

In movie shooting, several factors restrict your composition, and impose requirements you just don’t always have in still photography (although other rules of good composition do apply). Here are some of the key differences to keep in mind when composing movie frames:

- Horizontal compositions only. Some subjects, such as basketball players and tall buildings, just lend themselves to vertical compositions. But movies are generally shot and shown in horizontal format only. (Unless you’re capturing a clip with your smartphone; I see many vertically oriented YouTube videos.) So, if you’re shooting a conventional video and interviewing a local basketball star, you can end up with a worst-case situation like the one shown in Figure 10.4. If you want to show how tall your subject is, it’s often impractical to move back far enough to show him full-length. You really can’t capture a vertical composition. Tricks like getting down on the floor and shooting up at your subject can exaggerate the perspective but aren’t a perfect solution.

Figure 10.4 Movie shooting requires you to fit all your subjects into a horizontally oriented frame.

- Wasted space at the sides. Moving in to frame the basketball player as outlined by the yellow box in Figure 10.4 means that you’re still forced to leave a lot of empty space on either side. (Of course, you can fill that space with other people and/or interesting stuff, but that defeats your intent of concentrating on your main subject.) So, when faced with some types of subjects in a horizontal frame, you can be creative, or move in really tight. For example, if I was willing to give up the “height” aspect of my composition, I could have framed the shot as shown by the green box in the figure and wasted less of the image area at either side.

- Seamless (or seamed) transitions. Unless you’re telling a picture story with a photo essay, still pictures often stand alone. But with movies, each of your compositions must relate to the shot that preceded it, and the one that follows. It can be jarring to jump from a long shot to a tight close-up unless the director—you—is very creative. Another common error is the “jump cut” in which successive shots vary only slightly in camera angle, making it appear that the main subject has “jumped” from one place to another. (Although everyone from French New Wave director Jean-Luc Goddard to Guy Ritchie—Madonna’s ex—have used jump cuts effectively in their films.) The rule of thumb is to vary the camera angle by at least 30 degrees between shots to make it appear to be seamless. Unless you prefer that your images flaunt convention and appear to be “seamy.”

- The time dimension. Unlike still photography, with motion pictures there’s a lot more emphasis on using a series of images to build on each other to tell a story. Static shots where the camera is mounted on a tripod and everything is shot from the same distance are a recipe for dull videos. Watch a television program sometime and notice how often camera shots change distances and directions. Viewers are used to this variety and have come to expect it. Professional video productions are often done with multiple cameras shooting from different angles and positions. But many professional productions are shot with just one camera, and with careful planning you can do just fine with your a6600 camera.

Here’s a look at the different types of commonly used compositional tools:

- Establishing shot. Much like it sounds, this type of composition, as shown at top left in Figure 10.5, establishes the scene and tells the viewer where the action is taking place. Let’s say you’re shooting a video of your offspring’s move to college; the establishing shot could be a wide shot of the campus with a sign welcoming you to the school in the foreground. Another example would be for a child’s birthday party; the establishing shot could be the front of the house decorated with birthday signs and streamers or a shot of the dining room table decked out with party favors and a candle-covered birthday cake. In this case, I wanted to show the studio where the video was shot.

- Medium shot. This shot is composed from about waist to head room (some space above the subject’s head). It’s useful for providing variety from a series of close-ups and also makes for a useful first look at a speaker. (See Figure 10.5, top right.)

- Close-up. The close-up, usually described as “from shirt pocket to head room,” provides a good composition for someone talking directly to the camera. Although it’s common to have your talking head centered in the shot, that’s not a requirement. In the middle left image in Figure 10.5, the subject was offset to the right. This would allow other images, especially graphics or titles, to be superimposed in the frame in a “real” (professional) production. But the compositional technique can be used with a6600 videos, too, even if special effects are not going to be added.

- Extreme close-up. When I went through broadcast training, this shot was described as the “big talking face” shot and we were actively discouraged from employing it. Styles and tastes change over the years and now the big talking face is much more commonly used (maybe people are better looking these days?) and so this view may be appropriate. Just remember, the a6600 is capable of shooting in high-definition video and you may be playing the video on a high-def TV; be careful that you use this composition on a face that can stand up to high definition. (See middle right, Figure 10.5.)

- “Two” shot. A two shot shows a pair of subjects in one frame. They can be side by side or one subject in the foreground and one in the background. This does not have to be a head-to-ground composition. Subjects can be standing or seated. A “three shot” is the same principle except that three people are in the frame. (See Figure 10.5, lower left.)

- Over-the-shoulder shot. Long a composition of interview programs, the “over-the-shoulder shot” uses the rear of one person’s head and shoulder to serve as a frame for the other person. This puts the viewer’s perspective as that of the person facing away from the camera. (See Figure 10.5, lower right.)

Figure 10.5 Establishing shot (upper left); Medium shot (upper right); Close-up (middle left); Extreme close-up (middle right); Two shot (lower left); Over-the-shoulder shot (lower right).

Lighting for Video

Much like in still photography, how you handle light pretty much can make or break your videography. Lighting for video can be more complicated than lighting for still photography, since both subject and camera movement are often part of the process.

Lighting for video presents several concerns. First off, you want enough illumination to create a useable video. Beyond that, you want to use light to help tell your story or increase drama. Let’s take a better look at both.

Illumination

You can significantly improve the quality of your video by increasing the light falling in the scene. This is true indoors or out, by the way. While it may seem like sunlight is more than enough, it depends on how much contrast you’re dealing with. If your subject is in shadow (which can help him from squinting) or wearing a ball cap, a video light can help make him look a lot better.

Lighting choices for amateur videographers are a lot better these days than they were a decade or two ago. An inexpensive incandescent video light, which will easily fit in a camera bag, can be found for $15 or $20. You can even get a good-quality LED video light for less than $100. Work lights sold at many home improvement stores can also serve as video lights since you can set the camera’s white balance to correct for any color casts. You’ll need to mount these lights on a tripod or other support, or, perhaps, to a bracket that fastens to the tripod socket on the bottom of the camera.

Much of the challenge depends upon whether you’re just trying to add some fill light on your subject versus trying to boost the light on an entire scene. A small video light will do just fine for the former. It won’t handle the latter. Fortunately, the versatility of the a6600 comes in quite handy here. Since the camera shoots video in Auto ISO mode, it can compensate for lower lighting levels and still produce a decent image. For best results though, better lighting is necessary.

Creative Lighting

While ramping up the light intensity will produce better technical quality in your video, it won’t necessarily improve the artistic quality of it. Whether we’re outdoors or indoors, we’re used to seeing light come from above. Videographers need to consider how they position their lights to provide even illumination while up high enough to angle shadows down low and out of sight of the camera.

When considering lighting for video, there are several factors. One is the quality of the light. It can either be hard (direct) light or soft (diffused) light. Hard light is good for showing detail, but it can also be very harsh and unforgiving. “Softening” the light, but diffusing it somehow, can reduce the intensity of the light but make for a kinder, gentler light as well.

While mixing light sources isn’t always a good idea, one approach is to combine window light with supplemental lighting. Position your subject with the window to one side and bring in either a supplemental light or a reflector to the other side for reasonably even lighting.

Lighting Styles

Some lighting styles are more heavily used than others. Some forms are used for special effects, while others are designed to be invisible. At its most basic, lighting just illuminates the scene, but when used properly it can also create drama. Let’s look at some types of lighting styles:

- Three-point lighting. This is a basic lighting setup for one person. A main light illuminates the strong side of a person’s face, while a fill light lights up the other side. A third light is then positioned above and behind the subject to light the back of the head and shoulders. (See Figure 10.6, left.)

- Flat lighting. Use this type of lighting to provide illumination and nothing more. It calls for a variety of lights and diffusers set to raise the light level in a space enough for good video reproduction, but not to create a particular mood or emphasize a particular scene or individual. With flat lighting, you’re trying to create even lighting levels throughout the video space and minimize any shadows. Generally, the lights are placed up high and angled downward (or possibly pointed straight up to bounce off of a white ceiling). (See Figure 10.6, right.)

- “Ghoul lighting.” This is the style of lighting used for old horror movies. The idea is to position the light down low, pointed upward. It’s such an unnatural style of lighting that it makes its targets seem weird and ghoulish.

- Outdoor lighting. While shooting outdoors may seem easier because the sun provides more light, it also presents its own problems. As a general rule of thumb, keep the sun behind you when you’re shooting video outdoors, except when shooting faces (anything from a medium shot and closer) since the viewer won’t want to see a squinting subject. When shooting another human this way, put the sun behind her and use a video light to balance light levels between the foreground and background. If the sun is simply too bright, position the subject in the shade and use the video light for your main illumination. Using reflectors (white board panels or aluminum foil–covered cardboard panels are cheap options) can also help balance light effectively.

Figure 10.6 With three-point lighting (left) and flat lighting (right).

Audio

When it comes to making a successful video, audio quality is one of those things that separates the professionals from the amateurs. We’re used to watching top-quality productions on television and in the movies, yet the average person has no idea how much effort goes in to producing what seems to be “natural” sound. Much of the sound you hear in such productions is actually recorded on carefully controlled sound stages and “sweetened” with a variety of sound effects and other recordings of “natural” sound.

Your a6600 has a pair of stereo microphones on its top surface, able to capture Dolby Digital Audio. You can plug an external microphone into the mic jack on the left side of the camera, or work with a microphone designed specifically for Sony cameras, such as the (roughly $140) Sony ECM-XYST1M mic (see Figure 10.7). Hook up Sony’s ECM-B1M shotgun mic or XLR-K3M XLS adapter kit with a pro microphone; you’ll get professional audio quality that can match any dedicated camcorder.

Figure 10.7 An external microphone can significantly improve your audio quality.

If you stick with the built-in microphones, you must be extra careful to optimize the sound captured by those fixed sound-grabbers. You will find an Audio Recording entry in the Camera Settings II-02 menu (it just turns sound on or off), along with an Audio Recording Level and Audio Level display entry. In the Camera Settings II-03 menu, you’ll find an Audio Out Timing entry (to compensate for a delay when viewing live video through the a6600’s HDMI port), and a Wind Noise Reduction on/off entry. The latter is a low-cut filter feature that can further reduce wind noise; however, this processing feature also affects other sounds, making a wind screen on the microphone itself far more useful. Your camera options were explained in Chapter 4.

Tips for Better Audio

Since recording high-quality audio is such a challenge, it’s a good idea to do everything possible to maximize recording quality:

- Turn off any sound makers you can. Little things like fans and air handling units aren’t obvious to the human ear but will be picked up by the microphone. Turn off any machinery or devices that you can plus make sure cell phones are set to silent mode. Also, do what you can to minimize sounds such as wind, radio, television, or people talking in the background.

- Make sure to record some “natural” sound. If you’re shooting video at an event of some kind, make sure you get some background sound that you can add to your audio as desired in postproduction.

- Consider recording audio separately. Lip-syncing is probably beyond most of the people you’re going to be shooting, but there’s nothing that says you can’t record narration separately and add it later. It’s relatively easy if you learn how to use simple software video-editing programs like iMovie (for the Macintosh) or Windows Movie Maker (for Windows PCs). Any time the speaker is off-camera, you can work with separately recorded narration rather than recording the speaker on-camera. This can produce much cleaner sound.

Lens Craft

I’ll cover the use of lenses with the a6600 in more detail in Chapter 12, but a discussion of lens selection when shooting movies may be useful at this point. In the video world, not all lenses are created equal. The two most important considerations are depth-of-field, or the beneficial lack thereof, and zooming. I’ll address each of these separately.

Depth-of-Field and Video

Have you wondered why professional videographers have gone nuts over still cameras that can also shoot video? The producers of Saturday Night Live could afford to have Alex Buono, their director of photography, use the niftiest, most-expensive high-resolution video cameras to shoot the opening sequences of the program. Instead, Buono opted for a pair of digital SLR cameras. One thing that makes digital still cameras so attractive for video is that they have relatively large sensors. That provides two benefits compared to cameras with a smaller sensor. In addition to improved low-light performance, the large chip allows for unusually shallow depth-of-field (a limited range of acceptable sharpness) for blurring the background; this effect is difficult or impossible to match with most professional video cameras since they use smaller sensors.

As you’ll learn in Chapter 12, a larger sensor calls for the use of longer focal lengths to produce the same field of view, so, in effect, a larger sensor allows for making images with reduced depth-of-field. And that’s what makes cameras like the a6600 attractive from a creative standpoint. Shallow depth-of-field makes it easier to blur a cluttered background to keep the viewers’ eyes riveted on the primary subject. Your camera, with its larger sensor, has a distinct advantage over consumer camcorders in this regard, and even does a much better job than professional video cameras.

Zooming and Video

When shooting still photos, a zoom is a zoom is a zoom. The key considerations for a zoom lens used only for still photography are the maximum aperture available at each focal length (“How fast is this lens?), the zoom range (“How far can I zoom in or out?”), and its sharpness at any given f/stop (“Do I lose sharpness when I shoot wide open?”).

When recording video, the priorities may change, and there are additional parameters to consider. The first two I listed, lens speed and zoom range, have roughly the same importance in both still and video photography. Zoom range gains a bit of importance in videography, because you can always/usually move closer to shoot a still photograph, but when you’re zooming during a shot most of us don’t have that option (or the funds to buy/rent a dolly to smoothly move the camera during capture). But, oddly enough, overall sharpness may have slightly less importance under certain conditions when shooting video. That’s because the image changes in some way many times per second (30/60 times per second), so any given frame doesn’t hang around long enough for our eyes to pick out every single detail. You want a sharp image, of course, but your standards don’t need to be quite as high when shooting video.

- Zoom lens maximum aperture. The “speed” of the lens matters in several ways. A zoom with a relatively wide maximum aperture (small f/number) lets you shoot in lower light levels with fewer exposure problems. A wide aperture like f/1.8 also enables you to minimize depth-of-field for selective focus. Keep in mind that with most zooms, the maximum aperture gets smaller as you zoom to longer focal lengths. A variable-aperture f/3.5 to 5.6 lens like the power zoom kit lens, offers a fairly wide f/3.5 maximum aperture at its shortest focal length but only f/5.6 worth of light capturing ability at the long end. Zooms with a wide and constant (not variable) maximum aperture such as f/2.8 are available, but they are larger, heavier, and more expensive.

- Power zoom. An ideal movie zoom should have a power zoom feature, and that’s available with Sony lenses with the PZ designation. PZ lenses offer smooth, silent zooming that’s ideal for video shooting. Mechanical zooming with other lenses during capture can produce jerky images, even with vibration reduction turned on. If you own a remote with a zoom button, such as the RM-VPR1, I recommend using that with your PZ lenses for smoother zooming. As I mentioned earlier, you can also mimic power zoom using the a6600’s digital zoom feature.

- Zoom range. Use of zoom during actual capture should not be an everyday thing, unless you’re shooting a kung-fu movie. However, there are effective uses for a zoom shot, particularly if it’s a “long” one from wide angle to telephoto. Most of the time, you’ll use the zoom range to adjust the perspective of the camera between shots, and a longer zoom range can mean less trotting back and forth to adjust the field of view. Zoom range also comes into play when you’re working with selective focus (longer focal lengths produce shallower depth-of-field) or want to expand or compress the apparent distance between foreground and background subjects. A longer range gives you more flexibility.

- Linearity. Interchangeable lenses may have some drawbacks, as many photographers who have been using the video features of their digital SLRs have discovered. That’s because lenses with mechanical zooming are rarely linear unless they were specifically designed for shooting movies. Rotating the zoom ring manually at a constant speed doesn’t always produce a smooth zoom. There may be “jumps” as the elements of the lens shift around during the zoom. Keep that in mind if you plan to zoom during a shot and are using a non-linear lens. In practice, those include virtually all the lenses at your disposal, aside from power zoom lenses, a special E-mount cine lens, or a cine lens in an entirely different mount that you can use with your a6600 with an optional third-party adapter.