Plug and play homes are prefabricated, modular units that can be installed rapidly and ready for immediate use. In principle, with modern shipping techniques, plug and play dwellings can be transported to, or relocated, anywhere worldwide. Unlike prefabricated houses, which require some on-site assembly and are typically permanent, plug and play houses require no assembly and can be moved. The two main aspects affecting their conception are therefore transportation and interior design, which will be discussed below.

The design of plug and play units is determined by their need to be easily transported without causing external or internal damage. During transit, weight becomes a crucial factor, which permeates other design decisions. The goal is to create units that are heavy enough to sustain maximum wind drag when erected, but not too heavy as to exceed the supporting allowance on rooftops, for example (Studio Aisslinger 2011). For such rooftop units, the weight allowed varies greatly from unit to unit. Some firms claim that their units are rooftop safe with an average weight of 2,900 kg/m2 (600 lb/sq ft), while others make the same claim with a weight of 230 kg/m2 (47 lb/sq ft) to a max of 820 kg/m2 (170 lb/sq ft) (Alchemy Architects 2011, Studio Aisslinger 2011). Regardless of the varying weights, however, it is important to verify roofing allowances before placing a plug and play home atop a flat roof.

Designing to facilitate transportation also involves protecting external building components. Windows and doors present a special challenge since they weaken the overall structure and are breakable. Rather than compromising and limiting the numbers of windows and doors, however, designers have developed methods to protect them during travel. One method consists of large, sliding protective panels over the windows. This allows for the design of units in which the facades are almost entirely made of glass. Furthermore, some designers have created units in which the doors and windows fold into the structure to protect them, which also provides more interior space when installed. It is also possible to use thick shutters, which can be closed to seal off the glass and add structural support, much like on hurricane-proof buildings. Designers have also suggested units that can mechanically retract inwards to protect them during transportation, and can then be extended back out at the push of a button (Galvagni 2011).

Protection of the interior is another factor that must be considered in plug and play homes, since furniture and appliances can be damaged during transportation. One of the best ways to solve this is by bolting down all appliances and having furniture built into the walls and floors (Aisslinger 2009).

Since plug and play houses are generally small, designers must consider interior design for a limited space. The goal is to create spaces that feel large while still being efficient and functional. While this includes many of the concepts covered in the chapter on small dwellings (see page 42), there are a number of principles that are uniquely relevant to plug and play homes. Furthermore, there exists an assumption that modular, transportable units are cheap and uncomfortable, and while this may have been true in the past, recent innovation and technology has created high-tech, aesthetically pleasing structures, which are sleek, efficient and light (Nio and Kuenzli 2003). In fact, because plug and play homes are smaller and less costly than traditional dwellings, designers are able to use more expensive materials, sophisticated technologies and customizable features to make them affordable and comfortable (Solomon 2011, Assasi 2008).

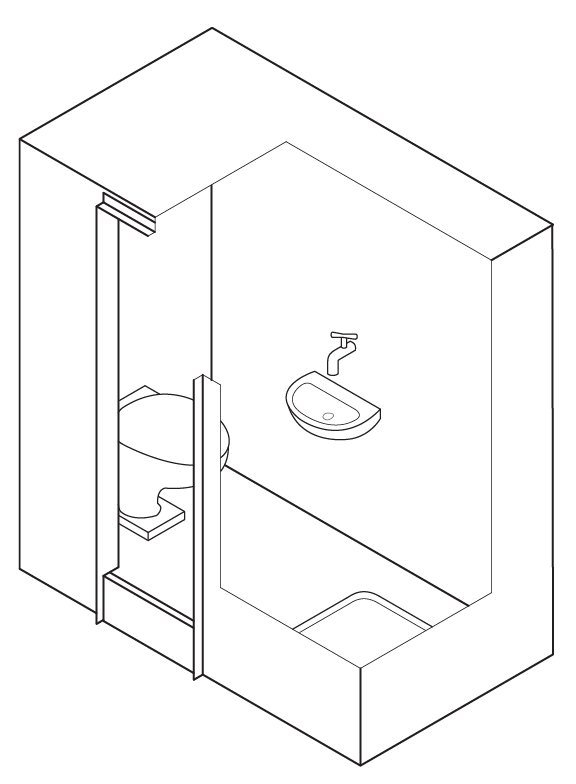

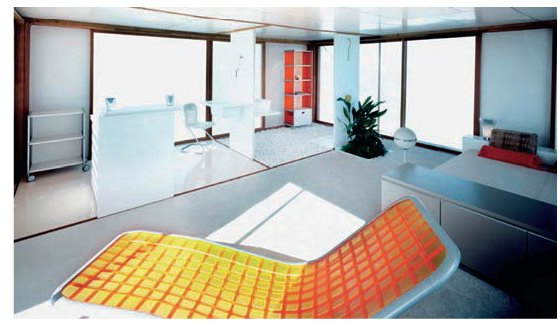

Figure 9.1 A prefabricated bathroom designed for use in a Plug and Play home.

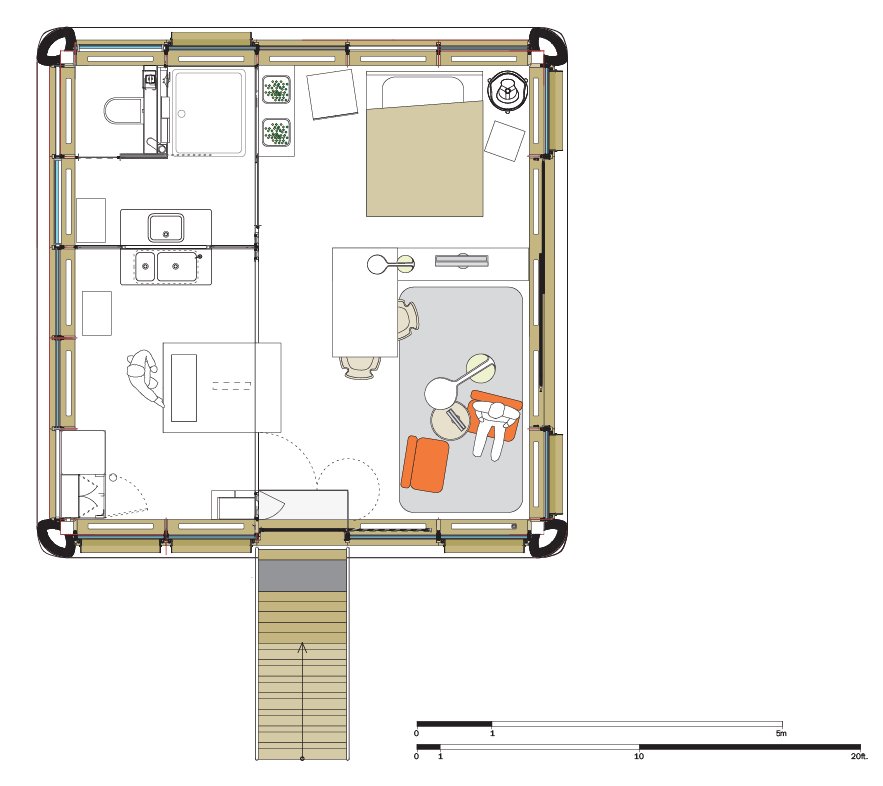

Where internal separation is needed it is possible to use sliding panels, which allow the occupant to customize the space (Studio Aisslinger 2011). Although these panels can range from translucent to opaque, it is recommended that they allow as much light through them as possible. Also, by placing the entrance stairs along the exterior wall, more space can be used for living. These stairs can also be designed to fold up or detach during transportation. Although the stairs can be made from any materials, it is recommended that a lightweight material, such as aluminium, be used due to its strength (Aisslinger 2009).

Built-ins are one method used to increase space efficiency; they are a useful tool to use when re-designating interior areas throughout the day, since beds, benches and tables can often be hidden in the walls and folded out when needed. It is also possible to create multi-use built-ins. In the LoftCube by Studio Aisslinger, for example, the shower head can easily be swivelled to serve as a watering hose for interior vegetation (Studio Aisslinger 2011).

The idea of built-ins can also be extended to the arrangement of utilities. To save space and minimize clutter, some designers have taken to embedding heating and cooling in the floors and walls. Furthermore, the dwellings are typically designed so that the windows, or roof, can open up to let outdoor air circulate within, which acts as natural air-conditioning. Many units are also equipped with mechanical ventilation systems (Aisslinger 2009).

Although plug and play homes require attachment of basic utilities, it is likely that future models will be off-grid designs. With improvements in technology such as solar cell development, battery life, water purification/recycling facilities and sewage cleaning facilities, it is plausible that some modules in future will be completely self-sufficient.

Many plug and play homes contain materials such as LEDlit frosted glass panels, marble countertops, floor-to-ceiling windows and lush carpets. In fact, they are constructed as ‘smart houses’, in which appliances and lighting are digitally controlled by a single touch-screen pad (Assasi 2008, Studio Aisslinger 2011).

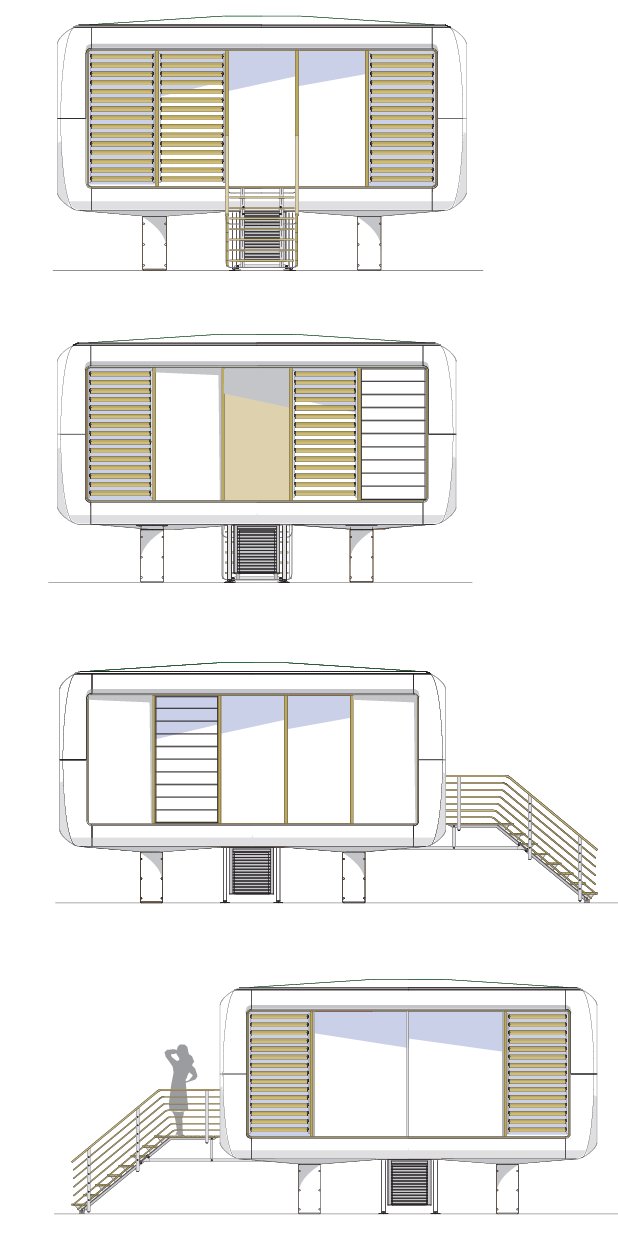

Furthermore, these units can sometimes be designed with customizable features, such as shutters and interior walls. In the Loftcube design for example, the selection of shutters and windows is easily customized to allow each unit to have different levels of privacy. The shutter systems can be independent for windows or facades, thereby permitting greater privacy control.

It is also possible to customize the units for future expansion by leaving room for the attachment of other modules. The function of these attachments can vary from home offices to new bedrooms, according to the needs of the inhabitant. While this is one way to solve issues related to live–work, expandable, adaptable and multigenerational dwellings, designers have also developed ideas for the assembly of a number of units. These assembled units are designed to be plugged into larger networks called ‘megastructures’. Some of the designs form housing towers, while others are ground level (Assasi 2008). In fact, to a large extent, some projects of this type already exist: both Habitat 67 in Montreal, Canada and the Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo, Japan were made of modular units. Contrary to the plug and play ideals however, modules from both these megastructures are very difficult, if not impossible to relocate (Assasi 2008).

Plug and play homes also have other applications. Firms, such as Lab Zero, are choosing to refurbish used shipping containers to promote the idea of re-use and recycling (Galvagni 2011). Some of these attempts are quite successful and have created cutting-edge architecture. Other firms are targeting prefabrication of affordable housing to be delivered to customers around the world, similar to the automobile industry, for example.

•Need to shorten construction times

•Built structures for a short duration and use

•Advances in prefabrication

•Need for urban densification

INNOVATIONS

•Advances in shipping techniques

•Development of lightweight materials

•Development of modular bathroom and kitchen units

•Innovation in small space design

•Refurbish shipping containers

9.1 PLUG AND PLAY DESIGNS | |

Project |

Loftcube |

Location |

New York, New York, USA |

Architect |

Studio Aisslinger |

High house prices have made home ownership difficult in many cities. Urban hubs like New York and London can only attract individuals for temporary stays, job opportunities or study.

The German architect Werner Aisslinger’s project, Loftcube, offers a dwelling that suits people with a ‘nomadic’ lifestyle and allows for temporary stays in dense urban areas. While its economic incentive is to market unused real estate in urban locations, the Loftcube is in fact a transportable penthouse that can be placed on rooftops, or other terrain such as mountaintops, islands and in forests.

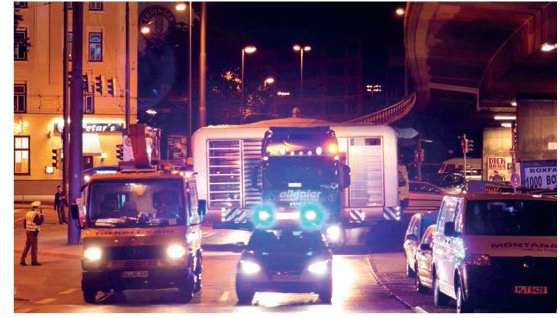

The cube measures 55 m2 (588 sq ft ) and is made of a steel and wood frame. To meet the demands of temporary living, the cube’s weight is calculated to allow transportation by helicopter and positioning by crane, while being structurally sturdy and heavy enough to withstand wind forces. For oversees transportation, the kit can be stored in a 12 m (40 ft) long container, and can be transported by cargo ship. Installation time from the initial placement of the cube to full living access for occupants can take as little as two days. Furthermore, many urban buildings are able to accommodate the additional weight of the Loftcube and no labour-intensive work is needed for their installation.

A view of a Loftcube unit.

The four facades of the Loftcube. The lightness of the unit was achieved by using glass curtain walls.

The interior of the Loftcube was designed efficiently and includes all basic functions.

The envelope can be clad with a wide selection of materials. Ranging from transparent glass panels for views of the outdoors to opaque timber louvres that help retain privacy. Buyers can choose whatever is most suitable to their lifestyle and location.

Indoors, the pod provides a 360-degree panoramic view. Even though there are four general spaces (living, kitchen, bathroom and bedroom), partitioning is installed for multifunctional usage. For example, both the kitchen and bathroom sinks share a common manoeuvrable tap. Portable furniture and sliding tracks can be constantly adjusted, so as to not to obscure the indoor view and light.

Lifting the Loftcube onto a rooftop.

Transporting the Loftcube.

Open plan and glass curtain walls helped alleviate the effect of a small-sized unit.

9.2 PLUG AND PLAY DESIGNS | |

Project |

Arado weeHouse |

Location |

Ontario, Canada |

Architect |

Alchemy Architects |

The weeHouse can be installed in four to eight hours.

The two glass facades let in light that makes a small space seem big.

A view into the space-efficient kitchen and dining areas.

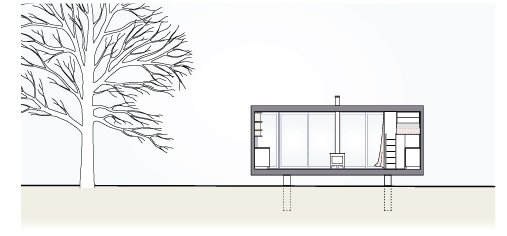

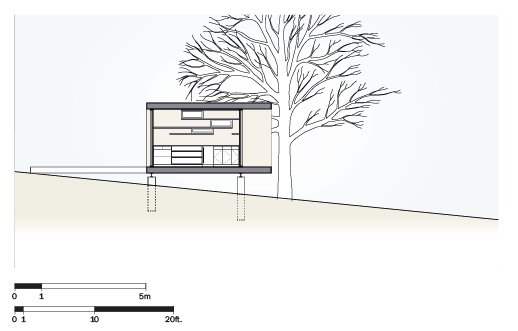

The weeHouse can be placed on several types of foundation, among them concrete pile, shown here.

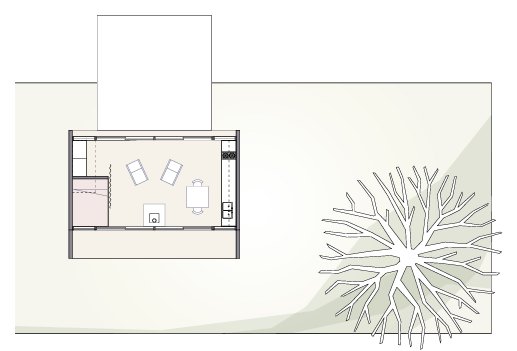

As a weekend cabin, studio, family home or an addition to an existing dwelling, the weeHouse, designed by Alchemy Architects in Ontario, Canada, is a dwelling that can accommodate a wide range of living demands and locations. Fabricated from a steel and wood frame in a factory, the unit can be delivered to any site by truck.

On-site, an installation crew takes approximately four to eight hours to bolt the unit to a foundation, which can be piers or perimeter. For occupants who wish to expand, there is room for the addition of more storage and a full basement. For dwellers who plan to live in the unit for a short period of time, piers are a more suitable foundation for labour and materials savings in case of dismantling. In partnership with independent plants in the USA and Canada, Alchemy works to economize time, budget and transportation.

It takes about six to nine weeks to prefabricate the frame and install tongue-and-groove bamboo flooring, interior gypsum board walls and furnishings. The standard weeHouse area is 41 m2 (438 sq ft) and it is clad with corrugated steel, available in a range of colours and finishes to be selected by the dweller. Depending on the occupant’s request, appliances, cabinets and fixtures can also be added to the basic unit. In an effort to complement locations with extreme weather, Alchemy can choose to install in-floor heating and small air-conditioning units that can be hidden in a back cabinet. On the other hand, clients who wish to purchase just a weeHouse ‘shell’ and finish it themselves can do so. The unit can also be custom-designed for the particular needs of each dweller.

Other factory-produced modules by the same designers include larger weeHouses, with stairs to an upper level, full-sized kitchen, garage and sleeping spaces. They are affordable in comparison to conventionally built houses and can be easily adapted to various sites.

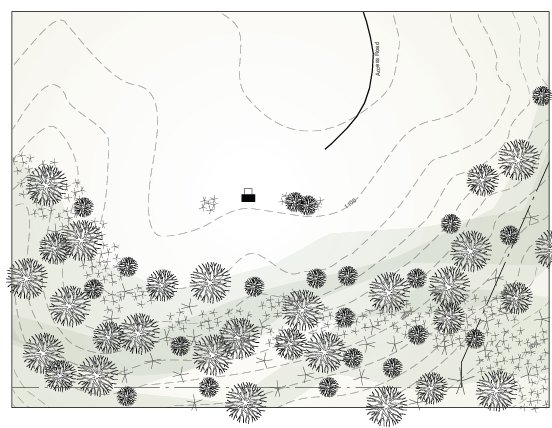

The siting of the unit minimizes damage to nature.

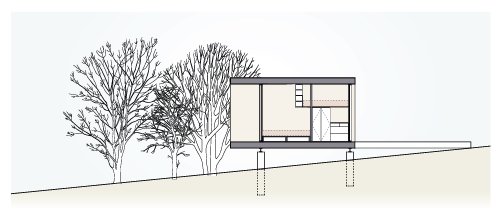

Cross section 1.

Cross section 2.

Cross section 2.