Declining birthrates, longer life expectancy and the ageing of the ‘baby boom’ generation have increased the number of senior citizens – those 65 years and over – in most Western societies. In countries such as Japan and Italy, their numbers are projected to account for up to 40 per cent of the population (CSIS 2011). This large-scale increase is expected to put strain on younger taxpayers in order to sustain social services. In 1950, there were 12 working people for every senior citizen in the world. By 2010, that ratio had dropped to 9 to 1 and is expected to drop further, to 4 to 1, by 2050 (PRB 2008). Contributions to health care and social security programmes are also expected to rise as a result of this demographic shift. In the USA, for example, the share of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) used to finance Medicare and Social Security has risen by 4 per cent since 1970, and is expected to rise further, to 15 per cent, by 2050 (PRB 2008).

Contrary to popular belief, few senior citizens live or wish to live in assisted living arrangements. According to polls, the majority of middle-aged and elderly people plan to spend the rest of their lives in their own home rather than move to an institutional care facility (Lawlor and Thomas 2008). Many private residences, however, are not designed to respond to the needs of an ageing person. Physical conditions caused by ageing and mental health deterioration can, at times, lead to accidents.

‘Ageing in place’ is a design concept that seeks to create barrier-free spaces that simplify daily tasks for those with reduced mobility and poor vision. Furthermore, senior citizenfriendly homes allow occupants to live on their own for longer, thereby reducing the need for costly support from families and the government (Salomon 2010).

Along with addressing the health of the economy, according to Lawlor and Thomas (2008), ageing in place also addresses one of the four fundamental psychological needs of people: independence. Typically, senior citizens – especially those who were previously very active – have problems adjusting to the physical limitations of an ageing body and still strive to lead a dynamic and socially active life. Studies have shown that successful designs for ageing in place, which allow senior citizens to remain autonomous, can improve their self-esteem, sense of purpose, community contribution and health (Salomon 2010). Since independent living leads to both a positive mental attitude and improved health, ageing in place designs not only benefit the occupants, but also society at large.

The ageing process is long and complex and because predicting all of the conditions that a senior citizen might encounter is difficult, there are many considerations that a designer must address early on. Conditions such as crippling arthritis, loss of vision, leg strength, stability and hearing – to name just a few – present uniquely different challenges to a designer. Furthermore, the house must initially be prepared for the aged when they are designed but before the preparations are actually needed by the occupants. A young couple will not want grab bars in their bathroom, but could wisely plan the means for their installation at a later stage. Another example is to design wider doorframes to accommodate the future use of walkers and wheelchairs, which is less costly if done early on. Housing needs to evolve and adapt easily and cheaply as the occupants’ requirements change.

One of the key issues that a designer needs to consider is fall prevention. In the US alone, falls are the second leading cause of injury-related deaths among senior citizens aged 55 to 79 (Lawlor and Thomas 2008). Obstacles, stairs, poor lighting and circulation and level changes in the building may cause such falls. Indoors, objects that can become obstacles should be kept to a minimum and placed along the walls, leaving central spaces free for circulation. In the bedroom, for example, a clear, obstacle-free path from the bed to the bathroom needs to be provided. It is also recommended that every room, including kitchens and bathrooms, have a minimum of a 1.5 m (5 ft) diameter circle of open space in the centre to compensate for reduced peripheral vision and potential wheelchair access.

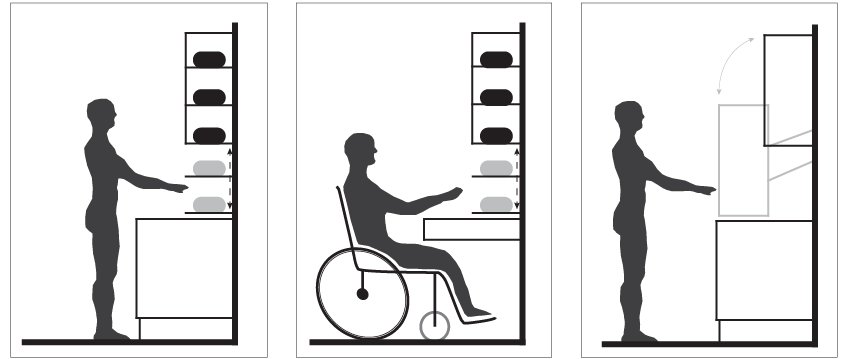

Figure 2.1Assistive devices for people with reduced mobility.

Joins between internal and external flooring levels and materials should be made smooth and even to prevent trips and falls. Furthermore, different elevations from room to room should be avoided, since they become hazardous as the occupant’s vision deteriorates. Having circulation space without sharp corners or turns is also recommended because it facilitates visual and oral communication should an occupant ever require urgent assistance. Good circulation design also allows for spaces that are wider than 81 cm (32 in) to permit wheelchair access. This access width is highly recommended – and at times mandatory – in every ageing in place design because it is of benefit to the occupants as they age, as well as to any visitors who might also require mobility assistance. Rooms, such as bathrooms and kitchens, with tiled floors and any rooms with wooden floor coverings should initially be designed with non-slip floors using wall-to-wall carpets or grooved flooring.

When stairs are included in a design, they need to be carefully planned. Primary living spaces should all be placed on the entrance level to minimize the use of stairs. If having a master bedroom on the ground level is not initially desired, the house should be designed to allow for such a transformation later on. Also, the stairs should have a solid handrail and be wide enough to accommodate a stairlift should one be needed later. The lower and top landings of the staircase should also be open, clear and visible to avoid accidents.

Some rooms may require more attention than others. The most important being the bathroom, bedroom and kitchen, which all require specialized appliances and aids. Facilities such as grab bars, extended bath ledges, walk-in showers, elevated dishwashers, adjustable cabinets and counters and knee spaces under sinks can greatly reduce back stress and slips. There are many innovative fixtures and appliances that can enable ageing in place and when planning such a home, designers should carefully consider them.

Windows and balconies can also be used by designers to enhance the quality of life for occupants of ageing in place designs. Large, well-placed windows can reduce feelings of isolation by permitting a street view of people and nature, while balconies allow occupants to get out in the fresh air and be in touch with others. It is also important to incorporate direct contact with nature indoors, since studies show that visual and physical proximity to the natural world improves mental health (Louv 2005). This can be done through the addition of sunrooms, plants and vegetation or water.

•Dramatic increase in the number of seniors

•Longer life expectancy

•Most seniors wish to age in their homes

•Technological developments

INNOVATIONS

•Design to accommodate several ageing stages

•Building initially for later adaptation

•Remote control technologies and robotics

•Flexible kitchen cabinets and storage

Figure 2.2Adjustable kitchen cabinets for easy reach.

Although there are already many contemporary ageing in place applications, the future seems to lie in smart technologies. Such house designs use digital and electronic systems to aid residents in performing daily tasks, which is especially helpful for senior citizens with reduced motor capabilities. Assistive technologies such as light clappers, remote control operated blinds and automatic doors already exist while others are still in the development phase (ICOST 2010). Furthermore, as the personal robot market is predicted to reach sales of US$19 billion in 2017, one can expect robots to be more common in the future (ABI Research 2010).

2.1 AGEING IN PLACE |

|

Project |

Villa Deys |

Location |

Rhenen, The Netherlands |

Architect |

Architectural Office Paul de Ruiter BV |

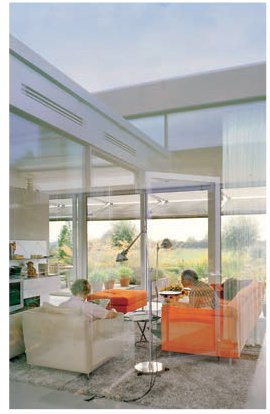

Nestled in an attractive setting in the Netherlands, Villa Deys, designed by architect Paul de Ruiter, blends in nicely with its environment. Conceived as a design for a couple in their sixties, who wish to continue to reside in the same house at an older age, the one-storey, 344 m2 (3,703 sq ft) home with its simple design and clever use of materials is barely perceptible within the landscape. The structure merges into the grassland and its gabioned facade resembles the design of traditional Dutch farmhouses.

The interior responds to the functional needs of the occupants. With a love for fitness and swimming, the integration of an indoor pool was one of the client’s primary wishes for the house.

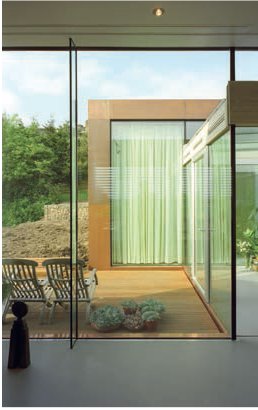

The wooden blinds in the southern facade can form a porch above the terrace.

The centrally located pool is safe for both the occupants and their visiting grandchildren and is protected by glass panels that can be locked up. Along with the vast amounts of light that enter from both ends of the house, the water and its reflections can be seen in the living areas, contributing to the relaxing atmosphere.

The living spaces are located around the pool and the open-plan design allows them to flow nicely into one another. The living room, kitchen and study are orientated to the south, with adjustable blinds to control the intensity of the penetrating light.

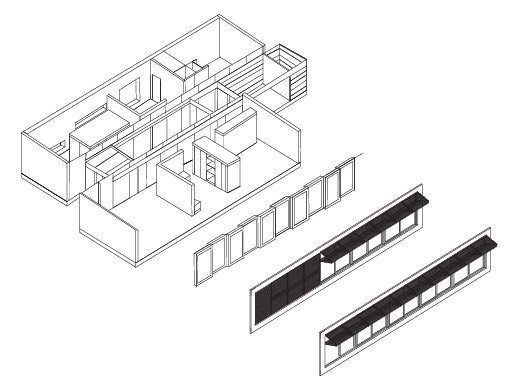

The two roof plates that make up the dwelling’s two sections.

The home can be regarded as two elongated boxes separated by a swimming pool.

The living spaces are located around the pool.

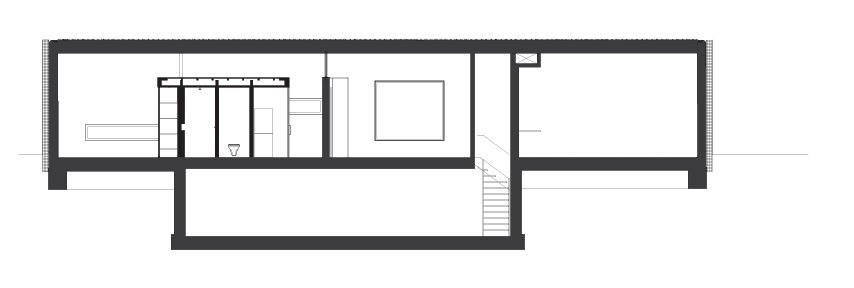

Section showing the pool in the dwelling’s centre.

Longitudinal section showing some of the dwelling’s living areas.

A section showing the garage on the right and the private quarters to the left.

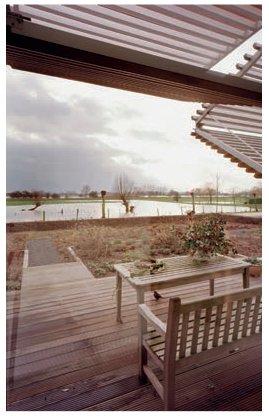

The southern facade consists of sliding doors, which can be opened or closed according to weather conditions. The blinds, made of horizontal wooden slats, form a porch above the outdoor terrace.

Most of the house’s appliances and fixtures can be operated electronically in order to respond to some of the challenges faced by the occupants. To avoid obstacles and to create an aesthetically pleasing effect, the control hubs are located in the basement walls and ceilings. Sliding doors, lighting and curtains have automated controls to avoid risky physical activity.

As the occupants age, it is assumed that the risk of accidents may rise. Therefore, light and colour differentiation was used in the initial design to prepare for possible deterioration of vision. And non-slip flooring around the bathroom and the kitchen was used to prevent accidents. In addition, the garage is designed to be converted into a nurse’s room to house live-in help should it be needed in the future.

View into the distance from the patio.

The living area.

View of the patio from the living room.

A passage to the outdoors equipped with an automatic door opener.