Ancient structures, such as the Greek temple of Apollo at Delphi or the Anasazi cliff dwellings in Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park, were built while considering natural features (Johnston and Gibson 2008). These principles were largely ignored in the post-World War II era; for example, when very little or no attention was paid to utilizing the sun, wind and topography to minimize energy consumption. The outcome was unsustainable residential subdivisions whose developers cleared the land and altered nature. Now turning back to sustainable practices, designers are reintroducing methods to construct dwellings on undeveloped virgin land while minimizing their environmental footprints.

When building with nature, a key consideration is preservation of flora and fauna. Constructing with minimal disruption to forests, for example, leads to advantages such as enhanced air quality, protection from the elements and storm water retention. Furthermore, having large trees around a house reduces overall energy consumption by up to 25 per cent due to both shading and protection from wind (Johnston and Gibson 2008). Retaining flora and fauna also enhances aesthetic and natural character, which in turn has been linked to improved mental health (Science Daily 2009). For designers, this is achieved primarily by avoiding unnecessary clearing of trees and the careful consideration of the site prior to construction.

Building with nature also involves the preservation of topography and natural drainage, on which plants and animals rely. Creating steep elevations with no vegetation, for example, can give rise to soil erosion or water run-off, both of which deprive vegetation of minerals, water and root support. With a decline of flora, deterioration of fauna follows, which can irrevocably change the character of a place. Therefore, planners must consider design strategies and recommend good practice before the site is chosen, during design and while construction is underway.

Another principle to consider is the utilization of wind for natural ventilation and the minimization of heat loss. The goal is to design according to wind patterns by allowing wind to enter the dwelling during summer months for natural ventilation. On the other hand, letting the wind blow into the dwelling during the winter months can lower temperature and raise heating costs. Therefore, it is important to plant new vegetation to divert wind or reduce its speed. It is also important to note that, while we will not discuss principles of narrow houses and passive solar design here (see pages 93 and 142), they are also key to the overall success and efficiency of dwellings built on greenfield sites with ample trees.

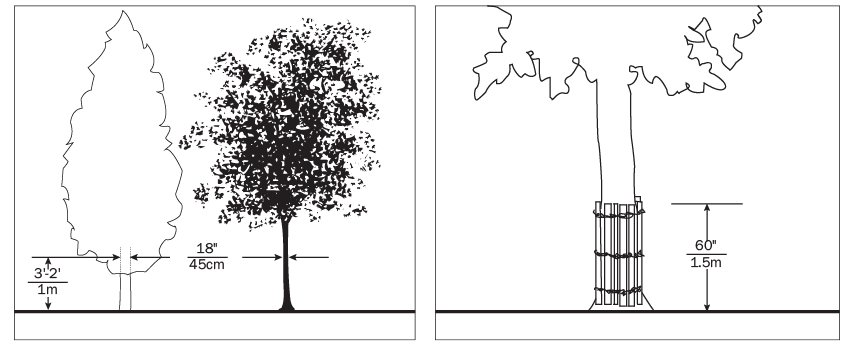

Before construction begins, it is important to plan the preservation of the local flora. Choosing a site in a clearing in a forest – or one with fewer trees – is recommended. If tree cutting is required, the site should be surveyed and a map made detailing which trees should be kept, and which ones cut. Emphasis should be placed on marking decaying trees for cutting while avoiding mature, healthy ones. The definition of a mature tree, however, varies according to the species and as such, the general size has a large range – from 45 to 100 cm (18 to 40 in) in trunk diameter measured at a height of 1 m (3.3 ft) above the ground (Friedman 2007, Nature First 2011a). When mature trees must be cut, it is suggested that they be relocated by professional contractors who can move them with up to 95 per cent success rates using specialized machinery (Nature First 2011b).

It is also recommended that areas adjacent to the site be fenced off to prevent heavy machinery from compacting the earth or accidentally destroying trees and shrubs (Nature First 2011b, Johnston and Gibson 2008). This is important because compacting the earth can severely reduce the soil’s ability to retain water or air, making future growth difficult. For areas near the site that cannot be fenced off, the top 15 cm (6 in) of topsoil should be removed and stored nearby, it can then be replaced once construction has finished. This will maintain the soil’s undiluted quality and internal aeration (Johnston and Gibson 2008, Abigroup 2011).

In order to preserve topography, the majority of decisions must be made when choosing the site. The objective is to select a place in which construction will alter the existing ecosystem the least. This means that building on steep terrain, of greater than 5 to 10 per cent, should be avoided unless special measures, such as retaining walls, are put in place to prevent soil erosion, or flat areas are found in hilly environments. Furthermore, building sites should be located parallel to contour lines to reduce elevation changes and the subsequent soil erosion. It is possible, however, to construct perpendicular to contour lines with split-level designs so long as efforts are made to prevent erosion and preserve the natural drainage of the site.

Figure 18.1: During construction, mature trees, whose circumference is greater than 45 cm (18 in) to the height of 1.5 m (60 in) above ground, need to be protected.

Locating a building on a hill can also greatly affect its temperature. In general, all sites in the northern hemisphere should be orientated south, and should be narrow builds in order to maximize passive solar gain. Building either high or low on the slope depends upon the local climate. Building low, for example, is advantageous in hot, arid climates where cool airflow is desirable. On the other hand, hot, humid regions necessitate a high position on a hilly slope due to the need for winds to cool off the building. For cold regions, it is recommended to build at lower elevations to avoid wind. In temperate regions, it is advised to build in the middle-upper regions for passive solar gain and natural ventilation (Johnston and Gibson 2008).

It is also important to avoid altering the site’s natural drainage by not adding man-made systems with sewers and storm water run-off, since they dry up the soil and put the existing flora at risk. Therefore, it is advisable to first prevent the destruction of the site’s existing vegetation and then, to plant shrubs and trees where needed to retain the soil. It is also encouraged to build retaining walls to prevent water run-off from gaining too much velocity. Roadways should be designed to guide water run-off into nearby vegetation, which can absorb it to prevent erosion.

Lastly, when building with nature it is possible to take advantage of the wind to reduce energy costs. Designers should first research the local annual wind patterns to determine in which direction the summer and winter winds blow. Special consideration should be taken near bodies of water, which have strong effects on wind direction and speed (Friedman 2007). The goal with natural ventilation is to direct summer winds to blow into the home and cool it, while blocking colder winter winds.

To block the winter winds, designers can use either man-made objects – sills, cornices, windwalls and fences – or natural objects, such as hills or conifer trees, which retain their leaves in winter (Johnston and Gibson 2008). For man-made windbreaks, avoiding impermeable material is advisable since it creates low-pressure zones on the leeward side of the material. Semipermeable materials, such as holed fences and vegetation, avoid this problem and are the most effective at blocking winter winds without side effects.

•Environmental awareness

•High heating costs

•Increased desire for personal comfort

•Stringent environmental laws

INNOVATIONS

•Creative landscaping

•Techniques for relocating trees

•Bio swells

•Improved storm-water management techniques

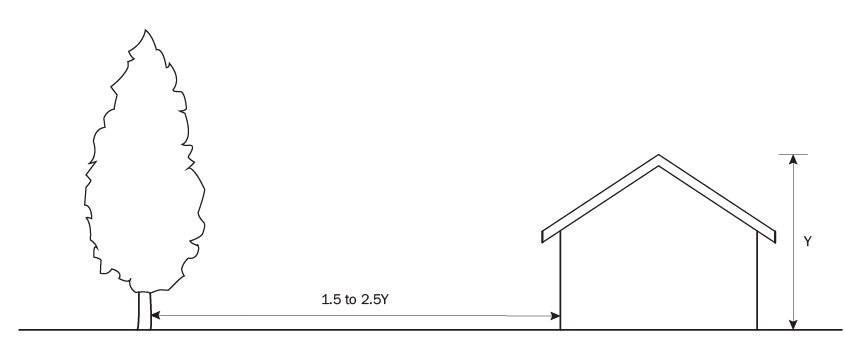

Figure 18.2:When using trees as windbreakers, they should be planted at a distance of 1.5 to 2.5 times the height of the building from the house.

When planting trees and low-lying vegetation as windbreaks, it is most effective to position them at a distance of 1.5 to 2.5 times the height of the building. This should prevent any excessive shade as well as any wind tunnels from forming between the windbreaks and the home. When the windbreak is a woodland or tree, however, the home should be located approximately 10 times the tree-to-house height ratio away from the woodland mass. For hot climate zones on the other hand, which require natural ventilation as a cooling mechanism all year long, designers should treat winter winds similarly to the existing summer winds.

As demand for housing grows, it is imperative that nature preservation principles be used to avoid destroying the environment that is in fact contributing to our lives. Building homes that integrate sun and wind harnessing technologies and topography into their designs not only benefits society in the short term, but also stands to maintain the natural beauty of ecosystems for years to come.

18.1 DESIGNING WITH NATURE | |

Project |

OS House |

Location |

Loredo, Cantabria, Spain |

Architect |

FRPO Rodriguez & Oriol Architecture Landscape |

Located in Spain’s Cantabria region, OS House is designed and built as equally ‘green’ as its surrounding natural landscape. The dwelling is situated along a seaside strip that consists of lush vegetation, grasses and rocky terrain. Designed by the firm FRPO Rodriguez & Oriol Architecture Landscape, the house was placed in a dug-out cavern 10 m (33 ft) from the edge of a cliff that faces the Bay of Biscay.

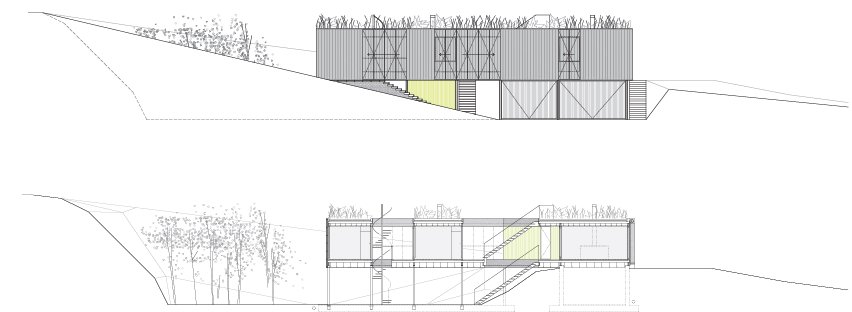

The building complements the downward-sloped plot on which the single-level, square-shaped house, which measures 360 m2 (2,799 sq ft), was sited. By placing the house 9 m (30 ft) down the slope, the newly formed dugout topography causes minimal visual disturbance to the original landscape. Furthermore, the house also features a large, visible green roof. In addition to blending the house effortlessly in with its encompassing lush green vegetation, the green roof is accessible and offers the dwellers a breathtaking view of the sea and the mountains.

The southern part of the house is supported by pillars housing living spaces and additional rooms.

The house was placed in a dug-out cavern.

The house is situated on the seaside strip of a cliff that faces the Bay of Biscay.

The dugout topography also offers an outdoor space that protects the occupants from the strong winds and the coastal sunlight. With the floor finished in polished concrete and access to the main level and garage, the house further incorporates a living space that links the home with its natural surroundings.

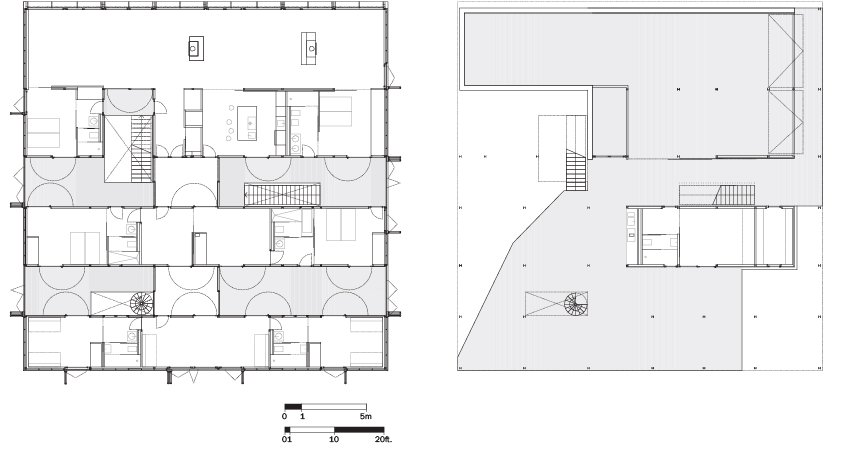

The layout of the house also takes into account the location. In the northern end, the living, dining and study areas are orientated towards the sea, while the southern part, supported by piers, contains a lounge and additional rooms.

The interior has white walls, hardwood flooring and minimal details. While floor-to-ceiling windows flood the living spaces with sufficient natural light during the day, the architects also equipped the house with artificial lights and open patios and balconies. Indoor comfort is achieved with under-floor radiant heating systems that were designed specifically for each room to optimize energy consumption. Other integrated green features include rainwater collection, which is reused for toilet flushing and watering the garden.

To protect the house from the windy and salty coastal air, OS House is clad with durable black zinc panels that mimic the surrounding, dark-toned rocky terrain. Moreover, because the panels were prefabricated, they can be easily dismantled and replaced if need be.

Elevation (top) showing the black zinc that the house was cladded with and a section (bottom) showing the living area and the roof.

Ground floor (left) where the living areas were oriented towards the sea. The roof plan is shown on the left.

The architects used eco-blocks as paving material. Their hope was to preserve the natural landscape and cause minimal impact by allowing water and sunlight to permeate while also offering an accessible pathway to the occupants and their automobiles between the house and the street.

The design of House OS ties it to its geographical location and unique site. The integration of green technologies that protect and preserve the environment makes the house a success.

The floors of the house are made of polished concrete.

View of the upper passageway and the exterior.

Site plan shows the house which faces the bay.

18.2 DESIGNING WITH NATURE |

|

Project |

Rantilla Residence |

Location |

Raleigh, North Carolina, USA |

Architect |

Michael Rantilla |

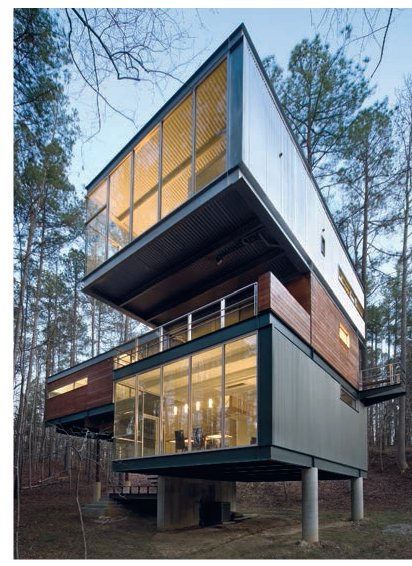

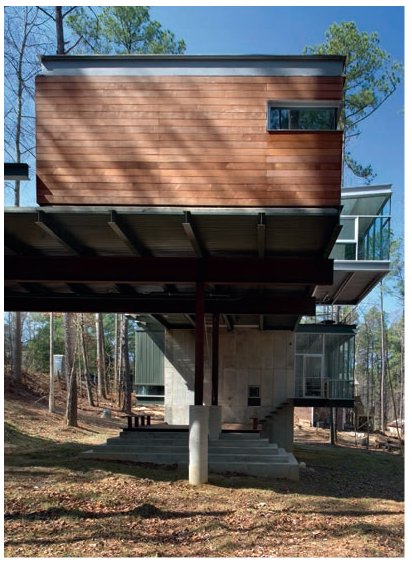

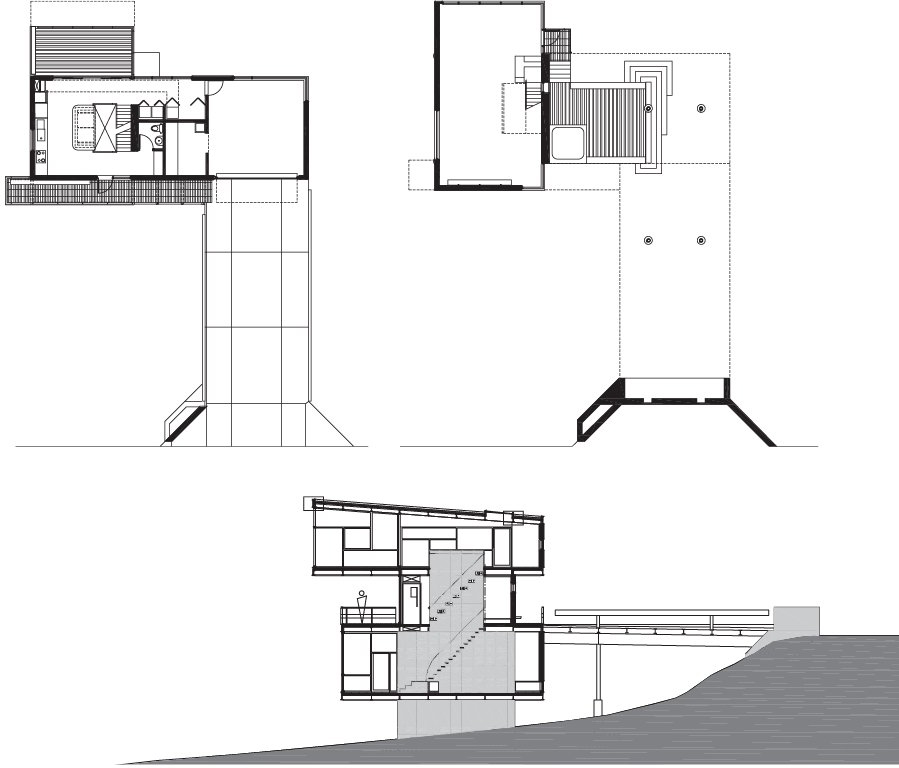

The Rantilla Residence is in a pristine wooded site near Raleigh, North Carolina. The city is also known as the ‘City of Oaks’, and the region is filled with beautiful forests, creeks and rivers. As architect and owner, Michael Rantilla encountered many challenges when creating his own dwelling, which takes full advantage of its magnificent surroundings. His design responded to the required zoning setbacks and site challenges, which included steep slopes and unworkable landscapes. The 232 m2 (2,500 sq ft) residence has a height of 12 m (40 ft), which is limited by the site constraints. Three volumes, rectangular-shaped boxes, have been ‘stacked’ on top of one another to form three levels, in order to take advantage of the unique views and orientation. The entire structure was built on concrete pillars to minimize harm to the landscape during construction. Furthermore, the pillars prevent annual floods reaching the house during the wet seasons. With minimal interruption to the ground below, the cantilevered rectangular volumes act as overhangs to create a number of distinctive outdoor spaces below.

The house is made-up of three rectangular volumes that have been stacked on top of each other.

The pillars prevent the annual fioods from reaching the house.

The house was constructed and sited in a region ˇlled with beautiful forests.

During construction, Rantilla, who also served as the general contractor, managed to protect all the major specimens of the surrounding trees, which included pine, sweet gum and oak. The intention was also to let wildlife continue to live in their habitat in the forest. Moreover, the preservation of trees and small vegetation served as a privacy protection, allowing the occupants to fully experience and connect to nature in their large-windowed rooms at the rear of the house.

In contrast, the roadsideorientated facade contains fewer openings. Each rectangular volume is clad with a different material, such as aluminium and exposed concrete, to distinguish its use. Upon approaching the Rantilla house, a wooded deck on the lowest level provides a large outdoor area leading to concrete steps to the entrance. The living room on the first floor and the kitchen and dining room on the second, have an industrial feel of sorts, due to their interior décor. Some spaces have exposed concrete walls while others have exposed white metal ceilings.

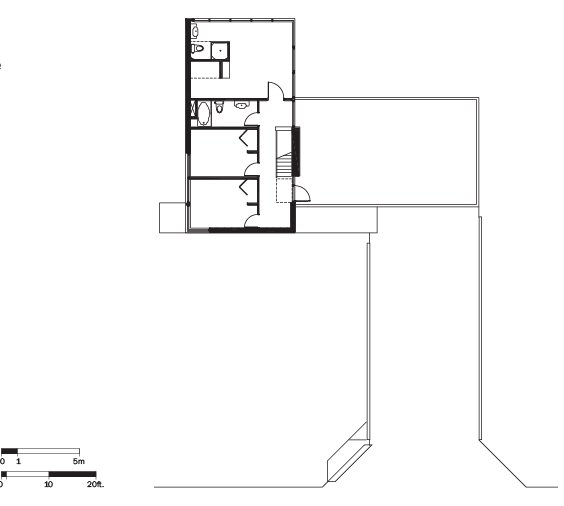

The second floor (top),first floor (middle left) and ground floor (middle right) offers view of the surrounding forest.

Cross section.

At the highest level, where the bedrooms are located, the floor-to-ceiling windows heighten the occupant’s experience of the surroundings and the proximity to the forest is enhanced by the leaves and branches that touch the glass windows.

Determined to face his challenges, Michael Rantilla has created a delightful dwelling that embraces the natural qualities of the site. Starting from a position of preserving the landscape and wildlife during the initial construction to strategically stacking each volumetric box to take full advantage of the pristine qualities of the woodland, the house can be appreciated from all perspectives.

The floor-to-ceiling windows around the living space bring the forest indoors.

View of the forest from the second-floor bedroom.

A view through the various levels.