An overview of current practices

Abstract:

In this chapter, we discuss global resource sharing practices in the early 21st century. Tips for successful international borrowing and lending are given.

Resource sharing plays a crucial role in education, democracy, economic growth, health and welfare and personal development. It facilitates access to a wide range of information, which would not otherwise be available to the user, library or country requesting it.

Introduction

Chapter 2 provides an overview of international intending activity and how it was conducted in years past. In this chapter, we discuss current global resource sharing practices in the early 21st century.

In conducting research for this chapter, we consulted several sources. Our first point of reference was our own experience, which is admittedly U.S.-centric. In our efforts to be more global in our approach, we conducted a survey of libraries to gather information about their international resource sharing practices. (Details about the survey and its follow-up are the focus of Chapters 5 and 6.) We asked these libraries to describe the typical life-cycle of an international request, including tools used when locating, requesting, shipping, circulating, and paying for international requests. Thirdly, we conducted a literature review (sources listed at end of chapter). As part of this literature review we consulted the RUSA STARS 2007 survey on international resource sharing (Baich et al., 2009) and the RLG SHARES study in the 1998 Model Handbook for Interlending and Copying (Cornish, 1988).

What we found, regardless of location, was that most international interlibrary loan requests follow the same pattern (see Figure 4.1).

What makes international resource sharing unique – and challenging – is the fact that these steps are often completed using different tools and methods than the ones typically used for domestic lending. The intent of this chapter is to illustrate some of the most commonly used tools and methods available for international resource sharing, giving libraries and other institutions a better awareness and understanding of the wide range of options available. It is always the responsibility of both the requester and lender to use these tools and methods in an ethical and standard manner, as noted in the IFLA standards.

The requesting process

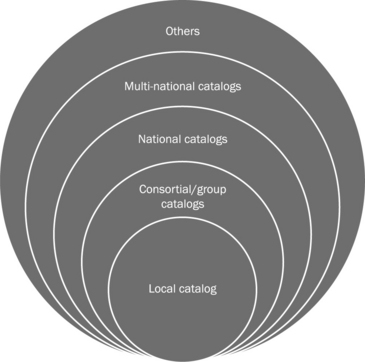

Nearly all libraries surveyed reported that local holdings are checked first to determine if an item is owned at the home institution. Staff cannot assume that the patron has checked local holdings first before initiating the loan request. This is also the point at which citations are verified, corrected, completed or sent back to the patron for more information. After confirming the item is not available from the library’s own collection, staff begin checking consortial, regional, or national sources. As Tina Baich points out:

With technological, language, and other barriers already hindering successful international ILL, taking the initiative to verify citations prior to sending them becomes almost essential to speed up the entire process; however, it is recognized that this is not always feasible because of language barriers. (Baich et al., 2009, 58)

It is usually at this point – verifying who owns the item – that resource sharing staff realize that this request is going to become an international one. Often ILL staff has already tried, perhaps several times, to locate or borrow the item domestically and the request has gone unfilled (see Figure 4.2).

Locating a lender

OCLC’s WorldCat is often the first resource consulted for international resource sharing – and with 200 million plus bibliographic records that represent more than one billion individual items held by participating institutions, it is indeed a highly valued first stop in the searching process. Of course, not all libraries – by any means – have loaded all of their holdings into WorldCat. As a result, librarians often report difficulty in locating lenders because many international libraries are not OCLC suppliers or participants (Baich et al., 2009). Notwithstanding this barrier, OCLC WorldCat can be an invaluable tool, and often the first consulted. However, do not neglect to expand your search using some of the additional tools listed below.

National, international and local catalogs

In this section, we provide a listing of other commonly used sources for locating international library items. While they are divided roughly into categories, be aware that categories may overlap. Web addresses and URLs listed are current as of February, 2011.

National libraries

It is advisable at the beginning of any international search to check for a national library or interlibrary loan ‘center.’ The IFLA code specifically advises a national policy that ‘should make clear whether incoming requests should go via the national centre (where one exists), and to what extent individual libraries will accept and satisfy international requests’ (IFLA, 2009).

Also, if your patron is looking for an item in a certain language, or published in a specific country, looking for a copy of that item in its ‘home country’ can be helpful. A quick Internet search for ‘National Library of [insert country name]’ will frequently give you an online catalog of national library holdings. Other sources for locating a national library include:

A few countries have also created sub-systems within their national (and sometimes international) system to better facilitate requesting. Some examples are:

![]() SUBITO (http://www.subito-doc.de/) – a document supply system headquartered in Germany used for resource sharing of photocopies and loans. Recently China has joined this system. An invoice is sent monthly comprising all orders.

SUBITO (http://www.subito-doc.de/) – a document supply system headquartered in Germany used for resource sharing of photocopies and loans. Recently China has joined this system. An invoice is sent monthly comprising all orders.

![]() NACSIS (http://webcatplus.nii.ac.jp/) – a comprehensive source, in Japanese, for Asian language materials with over 93 millions holdings (as of March 2007). See http://www.nii.ac.jp/CAT-ILL/en/ for more information.

NACSIS (http://webcatplus.nii.ac.jp/) – a comprehensive source, in Japanese, for Asian language materials with over 93 millions holdings (as of March 2007). See http://www.nii.ac.jp/CAT-ILL/en/ for more information.

![]() CISTI – National Research Center Canada (http://cisti-icist.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/eng/ibp/cisti/index.html) – a major document supply source for information in all areas of science, technology, engineering and medicine.

CISTI – National Research Center Canada (http://cisti-icist.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/eng/ibp/cisti/index.html) – a major document supply source for information in all areas of science, technology, engineering and medicine.

![]() AMICUS in Canada (http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/amicus/index-e.html).

AMICUS in Canada (http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/amicus/index-e.html).

![]() COPAC (http://copac.ac.uk/) – for materials held in libraries throughout the United Kingdom, including Trinity College Dublin Library in Ireland. COPAC contains the catalogs of all the UK National Libraries, a wide range of major university libraries, as well as specialized collections such as the National Art Library.

COPAC (http://copac.ac.uk/) – for materials held in libraries throughout the United Kingdom, including Trinity College Dublin Library in Ireland. COPAC contains the catalogs of all the UK National Libraries, a wide range of major university libraries, as well as specialized collections such as the National Art Library.

International catalogs

There are a few ‘meta-catalogs’ available that can also help you find sources for materials quickly:

![]() OCLC’s WorldCat (http://www.worldcat.org/) – a comprehensive resource linking most U.S. libraries and many international libraries or library systems in a single catalog. Often the first place librarians around the world start when looking for international sources.

OCLC’s WorldCat (http://www.worldcat.org/) – a comprehensive resource linking most U.S. libraries and many international libraries or library systems in a single catalog. Often the first place librarians around the world start when looking for international sources.

![]() The German Virtual Catalog (http://www.ubka.uni-karlsruhe.de/kvk_en.html) – this meta-catalog ‘that simultaneously searches some of the biggest union catalogs in Europe, the United States and elsewhere,’ is frequently cited as a source for non-OCLC libraries and an excellent place to start (see Figure 4.3).

The German Virtual Catalog (http://www.ubka.uni-karlsruhe.de/kvk_en.html) – this meta-catalog ‘that simultaneously searches some of the biggest union catalogs in Europe, the United States and elsewhere,’ is frequently cited as a source for non-OCLC libraries and an excellent place to start (see Figure 4.3).

Other sources

Listservs, or online email discussion groups can be excellent sources of holdings information. ShareILL (http://shareill.org) is an interlibrary loan wiki that is maintained and updated by librarians around the world and is useful for locating a source of information. Other ILL-specific organizations, such as the Global ILL Framework Project (http://www.nccjapan.org/illdd/gifproject.html), a collaborative agreement between North American and Japanese Libraries, can be helpful for participating institutions.

One source merits specific mention – the British Library (http://www.bl.uk/). Recognized worldwide as an essential resource, their holdings include over 14 million books, 920,000 journal and newspaper titles, 58 million patents, and three million sound recordings. Their fee-based service lends materials internationally and makes high-quality photocopies or digital scans of content with a remarkably fast turnaround time.

These tools are by no means exhaustive. As the information world expands dramatically so will the resources that organize and access it. These resources can, however, provide some solid starting points in the discovery and retrieval process.

A word about government documents

Government documents are in a category by themselves. Many of the above sources may own government documents and be willing to lend, but there could be better sources. Assuming the document is not classified, it might be freely available online – this is particularly true for documents published after 2000. An Internet search by the document title is often all that is needed to pull up a full text PDF or HTML version of the document.

If an Internet search does not bring the document up fairly quickly, it is often wisest to go straight to the publishing source’s website, whether that is the United Nations, a nongovernmental agency, or a government agency in a particular country.

For non-governmental agencies, the World Association of Non-Governmental Organizations or WANGO (http://www.wango.org/) is a good place to start. For United Nations Documents, ODS or the Official Document System of the United Nations (http://documents.un.org/) is another useful source. According to the website description, it ‘covers all types of official United Nations documentation, beginning in 1993. Older UN documents are, however, added to the system on a daily basis. ODS also provides access to the resolutions of the General Assembly, Security Council, Economic and Social Council and the Trusteeship Council from 1946 onwards.’

The shipping process

Borrowing library: the request is sent

Now that you’ve located a holding library, you need to find the best way to submit your request. While many libraries accept interlibrary loan requests via multiple methods, they usually have a preference.

Check first to see if the lending library uses any kind of automated requesting system, such as OCLC, DOCLINE, Relais, RACER, VDX, or other system. You may already be a member of this system. There may be a ‘request’ icon or link (although not always in English) within the catalog that you can use. Another helpful trick is to search the library website for an interlibrary loan page – frequently this will contain information for international libraries wishing to borrow materials and include instructions for placing requests.

If you cannot find any information about how to borrow materials, you may want to send a request via email, fax, or postal mail. The IFLA code gives very specific guidelines about what should be included in these request forms/letters:

Subject, Body, Date, Name of supplying library, Need by date, Type of search, Bibliographic description, Call number or verification source, Cost information, Preferred method of delivery, Copyright compliance, Copyright identification, Full address of requesting library, Delivery address, Billing address. (IFLA, 2009)

In addition to it being a professional courtesy, including this information will expedite your request and increase the chances that the owning library will be able to fill your request.

You may or may not receive a reply. Most libraries will reply or send the item within 1–2 weeks, though if sent via postal mail it may be delayed an additional week or two. If you do not receive a reply within 3–4 weeks, it is reasonably safe to assume that the library will not be able to fill your request. Be prepared though, that once you have requested the item it may suddenly appear at your library without warning. If you have already sent the request on to another international library, you may find yourself with two copies of the same item.

Lending library: the request is received

If you are a library on the receiving end of an international borrowing request, you have the privilege of being able to extend your knowledge and collection to further the research of library patrons far, far away. You are also in the position of needing to decide if you are able to loan the material and if so, how best to get the item to the borrowing library or patron. Several questions you will need to answer are:

![]() Did the requesting library give me all the information I need to fill this request? If not, you may have to contact the library to ask further questions.

Did the requesting library give me all the information I need to fill this request? If not, you may have to contact the library to ask further questions.

![]() Does my library already have a policy on what we will or will not lend internationally?

Does my library already have a policy on what we will or will not lend internationally?

![]() Is the item available? Checked out? Due soon?

Is the item available? Checked out? Due soon?

![]() Should I lend it or copy it? What condition is the material in? Do I have the authority to lend this internationally or should I get approval, and from whom?

Should I lend it or copy it? What condition is the material in? Do I have the authority to lend this internationally or should I get approval, and from whom?

![]() Are there copyright restrictions on what I can do with these materials? Copyright law varies from country to country and is, in many places, under review. It behooves interlibrary loan librarians to stay informed of current copyright law in their country and how it may impact their operations. The same can be said for licensing restrictions for electronic content. Your library subscription to an electronic journal may have come with a licensing restriction that does not permit the copying or transmission of an article outside national borders.

Are there copyright restrictions on what I can do with these materials? Copyright law varies from country to country and is, in many places, under review. It behooves interlibrary loan librarians to stay informed of current copyright law in their country and how it may impact their operations. The same can be said for licensing restrictions for electronic content. Your library subscription to an electronic journal may have come with a licensing restriction that does not permit the copying or transmission of an article outside national borders.

![]() Will I charge the library for this service? If so, how much?

Will I charge the library for this service? If so, how much?

These questions are very similar to questions asked for any resource sharing request, but have an added dimension since the item will be traveling internationally.

Once you have decided if you can fill the request – whether your answer is yes or no – it is a professional courtesy to let the requesting library know as soon as possible so they can be expecting the material, possibly notify their patron or can begin the search and request elsewhere.

Lending library: electronic delivery

If you will be lending the material requested, you should clearly state your costs, currency, and preferred method of payment. If the requesting library did not state a maximum acceptable cost and method of payment at the time of request, you may want to wait for a ‘we agree’ reply before proceeding to the next step. This gives the requesting library the opportunity to retract their request if they cannot or do not want to pay your fees.

Libraries use a variety of hardware and software systems to scan and send materials, with Adobe Acrobat software clearly preferred. For large libraries, an increasingly common solution to providing fast, high-quality digital scans is the BSCAN/Bookeye product, a robust new integrated hardware and software system. File transfer software such as Ariel or Odyssey provide fast, increasingly automated transmission of electronic documents. Email is another common method of file transfer. Except for Ariel (which uses TIF files), PDF format is generally preferred, although if you are scanning images or other files in need of high-resolution then TIF or JPEG format may be preferable. You should scan at a high-enough resolution for good reading quality, but not so high that the file becomes unnecessarily large. Large files may not be transferable via email. Also, it is important to pay attention to the material being scanned to avoid damage – many items requested internationally are rare materials and must be handled with care. The American Library Association, Association of College and Research Libraries Section have some excellent guidelines on the handling of rare materials for resource sharing. These guidelines can be found at: http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/acrl/standards/rareguidelines.cfm.

It is important to note the delivery address of the requesting library. It will often include preferences for receiving digital files. Some libraries prefer email attachments; others have automated systems such as Ariel or Odyssey.

Lending library: physical delivery

If you decide to lend a print item, you have a few more decisions to make. The first is whether you want to place any restrictions on the use of your item by the borrowing library or patron. For rare, non-print or media items (DVDs, CDs, etc.) many libraries designate an in-library-use-only restriction. The second decision is how long your loan period is going to be. Remember that you will need to allow for transit time both to and from the requesting library. Many libraries choose a 4–6-week loan period. The third consideration is how to ship the item to the requesting library.

Costs for international shipping vary by vendor, speed, weight, distance, and add-ons such as tracking or insurance. Costs can range from reasonable to exorbitant, so it pays to do some research. Many libraries surveyed reported that they use private courier companies such as UPS, DHL, or FedEx. For many countries these more expensive commercial providers might be the only option for international shipping. Libraries in some countries – particularly the U.S. – can use their national postal system for international shipping. Where possible and affordable, choose a shipping method with tracking capabilities. If the item is rare or fragile you will probably want to add insurance and/or delivery confirmation.

You may want to stipulate that the requesting library return the item by the same method you used to ship it – including tracking, insurance, or delivery confirmation if you added those options. Finally, you will likely need to complete customs forms for your shipment. Your shipping vendor can usually assist you with determining which forms you need and how to complete them – a customs declaration form and/or proforma invoice are commonly requested.

Fees and payments

Whether you send a digital scan or ship a print item, you will need to determine your fees. Even libraries that do not typically charge for domestic resource sharing often charge for requests from international libraries – usually because of the associated extra staff time, shipping fees, and possible replacement costs if the item is lost or damaged. If you have clearly stated your charges ahead of time (when responding ‘yes’ to the request) the requesting library is aware of your fees and will not be unduly inconvenienced or surprised when an invoice arrives.

Fees for international resource sharing vary based on proximity, weight of item, number of pages (for scans), rarity, and whether the requesting library belongs to a group or consortium with previously negotiated fees. Fees typically range from US$7 to US$25 for scans (up to a certain page limit), and US$15–45 for loans.

Methods of payment

With the added complication of currency conversion, the method of payment is important and should be stated at the time of agreeing to loan. Some libraries cannot pay by certain methods. It is helpful to offer a couple of different options for payment.

![]() Reciprocal agreements – some libraries, groups, or consortia have agreed not to charge each other for resource sharing. This works most effectively when the sharing is evenly distributed and no individual library is providing the bulk of the service.

Reciprocal agreements – some libraries, groups, or consortia have agreed not to charge each other for resource sharing. This works most effectively when the sharing is evenly distributed and no individual library is providing the bulk of the service.

![]() Standard invoices – these are usually payable by check. While this is a common method, it can be problematic due to currency conversion. Also, some libraries can only issue checks in their home currency and this is not always acceptable to the lending library.

Standard invoices – these are usually payable by check. While this is a common method, it can be problematic due to currency conversion. Also, some libraries can only issue checks in their home currency and this is not always acceptable to the lending library.

![]() Deposit accounts – if you frequently borrow or lend with a particular international library it may save time (and earn a discounted rate) to set up a deposit account.

Deposit accounts – if you frequently borrow or lend with a particular international library it may save time (and earn a discounted rate) to set up a deposit account.

![]() Credit cards – this a common and easy-to-use method as it automates currency conversion. Some libraries have a secure, online web-based form where the requesting library can enter payment information. Others send a credit card payment form with the item (or email a PDF form). The requesting library can complete the form and return it by fax or postal mail. IMPORTANT: Credit card information should never be transmitted via email – email is not secure. Your credit card information could be stolen and fraudulently used.

Credit cards – this a common and easy-to-use method as it automates currency conversion. Some libraries have a secure, online web-based form where the requesting library can enter payment information. Others send a credit card payment form with the item (or email a PDF form). The requesting library can complete the form and return it by fax or postal mail. IMPORTANT: Credit card information should never be transmitted via email – email is not secure. Your credit card information could be stolen and fraudulently used.

![]() IFLA vouchers – these are international resource sharing coupons sold by IFLA (http://archive.ifla.org/VI/2/p1/vouchers.htm). These coupons, which come in full and half values, are traded among borrowing and lending libraries like currency. They can be sent via postal mail or included with the item when returning. See Figure 4.5.

IFLA vouchers – these are international resource sharing coupons sold by IFLA (http://archive.ifla.org/VI/2/p1/vouchers.htm). These coupons, which come in full and half values, are traded among borrowing and lending libraries like currency. They can be sent via postal mail or included with the item when returning. See Figure 4.5.

![]() Automated payment systems – some automated resource sharing systems such as OCLC’s IFM (Interlibrary Loan Fee Management) or DOCLINE’s EFTS (Electronic Funds Transfer System) offer their own payment method. If one is available, use it! They are fast, efficient, and assist with currency conversion.

Automated payment systems – some automated resource sharing systems such as OCLC’s IFM (Interlibrary Loan Fee Management) or DOCLINE’s EFTS (Electronic Funds Transfer System) offer their own payment method. If one is available, use it! They are fast, efficient, and assist with currency conversion.

Finally, if you receive a request for an item that you are not able to fill, it is a professional courtesy to inform the borrowing library of that action. International requests fail for any number of reasons. However, if an item will not be sent to the requestor, IFLA guidelines state that a reason should be provided. (Table 4.1) OCLC and DOCLINE also provide options for notifying a requestor why an item cannot or will not be sent.

Table 4.1

| Group | Code | Message |

| A. Not yet available | 1 | In process, the item has been received but is not yet ready for use |

| 2 | The item is on order, but has not yet been received | |

| 3 | Title owned but requested part/issue not yet received | |

| B. Held but temporarily not for supply | 4 | The item requested is currently on loan or in use by a reader |

| 5 | The item is at bindery | |

| 6 | The item is on course reserve and not available for loan | |

| C. Held but not for supply | 7 | The item has been lost from stock |

| 8 | The item is non-circulating (we hold the item but it is not available for loan) | |

| 9 | The item is missing from stock, but may be available in the future | |

| 10 | The item cannot be loaned because it is damaged and/or in poor physical condition | |

| 11 | Copyright regulations do not permit this item to be copied | |

| D. Not held | 12 | The title or item is not held |

| 13 | The part required is not held | |

| 14 | Item not held, name and address of a potential supplier to follow | |

| E. Conditions of supply | ||

| Financial | 15 | The cost of the ILL is greater than the maximum cost indicated on the request form. If this cost is acceptable, please reapply |

| 16 | Payment required before ILL request is processed | |

| Time | 17 | Being processed for supply |

| 18 | Preferred delivery time not possible | |

| Delivery | 19 | Request does not include indication of copyright compliance |

| 20 | Unable to send via the type of delivery method requested | |

| 21 | Client signature required | |

| Use | 22 | The supplied item may only be used within the requesting library |

| 23 | Supplied item only to be used under the supervision of a librarian and/or in the special collections department | |

| 24 | Supplied item not to be photocopied and/or reproduced | |

| F. Not found | 25 | Unable to trace the item with the information quoted. Please check your reference |

| 26 | No locations have been found | |

| G. Others | 27 | Other |

| 28 | Library closed |

Source: Author supplied

Borrowing library: the request is received

This is often the most rewarding point in the international resource sharing process – the item so laboriously researched, located, requested, and shipped finally arrives at the requesting library! Depending on the shipping method the item may take between 24 hours (digital files) to several weeks (postal mail from faraway countries) to arrive.

Digital files may be received via any of the methods listed in your request – CD, DVD or zipped file, PDF attachment, Ariel or Odyssey transmission, or FTP transfer. Shipped items will generally arrive via the method preferred by the lending library.

As with all items received via resource sharing, it is extremely important to note any use restrictions that the lender has placed on the item. Print items should be carefully examined and any damage noted and reported to the lender. This helps to prevent your library from being charged for items that may arrive damaged.

Circulate the item to your patron according to the use restrictions of the lending library (if any) for the loan period specified. These special conditions are generally noted on the paperwork included with the print item.

After the patron is finished with the item, make sure to return it to the lending library via the method specified. If the lending library did not specify a method, try if possible to return the item through a trackable method, packaging carefully and including all relevant paperwork.

Lastly, if payment has not already been made to the lending library, now is the time to process any invoice or other request for payment. Some libraries include payment with the returning item, saving postage.

Statistics

Whether you are new to international resource sharing or have been sharing materials across borders for many years, you will inevitably be asked to produce statistics on your activities. You will want to find a way to keep track of how many requests you fill, through what method, for which items, and for which libraries. As mentioned earlier, it’s helpful to fold your international resource sharing activities into your current workflow as much as possible, and whatever system you already have likely includes statistical capability. Some interlibrary loan software systems (such as ILLiad) will allow you to ‘tag’ lending/borrowing libraries as ‘international’ which helps when generating reports. If necessary, keep a written or digital log of your activity. If nothing else, it will aid in building your own set of procedures for resource sharing. You will have a log of contacts and methods that do (or do not!) work effectively.

Issues and challenges

Time

The time it takes to verify holdings, place a request, re-request, wait for arrival, make payment, and ship the item back is significant. For this reason alone, many libraries limit their international resource sharing efforts. However, for patrons who can afford to wait and really need a particular item, it is frequently worth the wait. Patrons should be warned that international requests may take significantly longer than ‘regular’ resource sharing transactions.

Fear of loss or damage

Many libraries fear losing items in the mail system or due to non-return by the international patron. However, most resource sharing librarians will tell you that the number of lost items is quite low, particularly when looked at as a percentage of overall resource sharing activity. Three easy ways to mitigate this fear are: scanning and sending digital files whenever possible, using a trackable shipping method, and not loaning irreplaceable items.

Logistics

International resource sharing requests are often fulfilled with tools, software, and systems not typically used by a resource sharing operation. This change from the familiar can be intimidating. Remember though that the first time is always the hardest, and after filing several international requests staff quickly become familiar with the new tools. A word of warning – avoid becoming complacent, whether in international or domestic resource sharing. The landscape is changing quickly. Systems, catalogs, technologies are constantly evolving. These new tools frequently open doors to resources previously unavailable.

Shipping costs

International shipping does cost more than domestic mail, but through careful comparison of rates you can often arrive at a reasonable shipping cost. Some libraries simply cannot afford to absorb this extra shipping cost – no matter how reasonable. Two additional ways to lower international shipping costs are to restrict lending to nations geographically close to you, and/or asking the patron to pay for some of the shipping costs.

Language barriers

Receiving written, faxed, emailed, or phoned communication in a language you do not speak can be one of the most frustrating (or the most amusing!) impediments to global resource sharing. Fortunately, with the advent of online, digital translations tools such as Google Translator and Babel Fish, this is one of the more easily scaled barriers. Be prepared though. These tools usually cannot translate context, idioms, or figures of speech, which can lead to baffling (and entertaining!) translations. If only for this reason, keep written communication simple, direct, and courteous.

Summary

Even though the logistics of international borrowing and lending of library materials can feel intimidating at first, it is also very rewarding to see a long-sought-after item arrive through the doors of your library. It is even more rewarding when that item is uniquely and particularly valuable to your patron. Searching, requesting, processing, shipping, and returning internationally loaned items is a skill that takes time and practice to master. There is rarely one, single, correct way to send a transaction. Keep in mind that the library on the other side of the request is eager to have their materials used, or to share your materials with their patron. Always remember, if you’re unsure about the next step in the process, don’t hesitate to send a simple email or message asking the other library for help or advice.

Useful resources

![]() Reference and User Services Association. American Library Association. ‘Interlibrary Loan Code for the United States.’ http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/rusa/resources/guidelines/interlibrary.cfm

Reference and User Services Association. American Library Association. ‘Interlibrary Loan Code for the United States.’ http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/rusa/resources/guidelines/interlibrary.cfm

![]() International Federation of Libraries and Institutions. ‘International Lending and Document Delivery: Principles and Guidelines for Procedure.’ http://archive.ifla.org/VI/2/p3/ildd.htm

International Federation of Libraries and Institutions. ‘International Lending and Document Delivery: Principles and Guidelines for Procedure.’ http://archive.ifla.org/VI/2/p3/ildd.htm

![]() International Federation of Library Assocations and Institutions. ‘IFLA Position on Copyright in the Digital Environment.’ http://www.ifla.org/en/publications/the-ifla-position-on-copyright-in-the-digital-environment

International Federation of Library Assocations and Institutions. ‘IFLA Position on Copyright in the Digital Environment.’ http://www.ifla.org/en/publications/the-ifla-position-on-copyright-in-the-digital-environment

References

Arlitsch, Kenning, Lombardo, Nancy T., Gregory, Joan M., Another Kind of Diplomacy: International Resource Sharing. Resource Sharing and Information Networks 2006; 18:105–120 (also accessed December 20, 2010 http://www.istl.org/00-summer/article3.html)

Baich, Tina, Jiping Zou, Tim, Weltin, Heather, Ye Yang, Zheng. Lending and Borrowing Across Borders: Issues and Challenges with International Resource Sharing. Reference & User Services Quarterly. 2009; 49(1):54–63.

Cornish, Graham P. Model Handbook for Interlending and Copying. Boston Spa: IFLA Office for International Lending and UNESCO; 1988.

IFLA International Resource Sharing and Document Delivery: Principles and Guidelines for Procedure 2009. http://www.ifla.org/files/docdel/documents/international-lending-en.pdf.

Massie, Dennis. The International Sharing of Returnable Library Materials. Interlending & Document Supply. 2000; 28(3):110–116.