The History of Visual Merchandising

Here the fish and poultry seller has created an artistic display of his wares, the design of which would not look out of place in the display lore of visual merchandisers today.

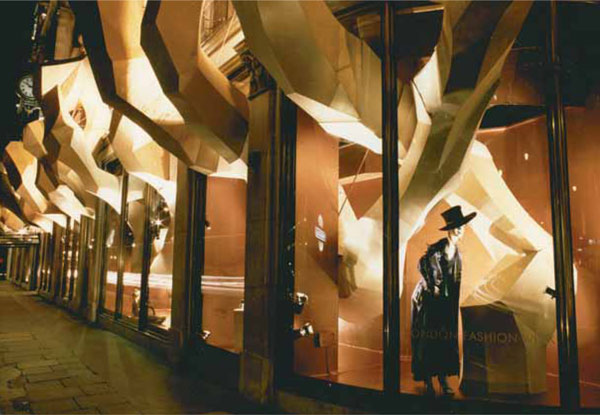

In these attention-seeking, award-winning windows designed by Thomas Heatherwick for Harvey Nichols in London, the scheme explodes through the glass onto the exterior of the store.

The first shopkeepers tried to lure consumers into their stores either by ostentatiously exhibiting their names or by displaying products in their windows or on tables in the street, proving that they were open for business and proud of their produce.

To this day, butchers still fill their windows with fresh meat that serves both as a display to attract customers and also shows the cuts available for sale that day. Florists often not only pack their windows with the finest blooms, but trail them outside the store and onto the sidewalk to entice customers across the threshold using color and scent. Similarly, barbers will sometimes push a chair with an unsuspecting client up to the glass window in order to prove their skill and popularity.

With the advent of new technology in the 1840s that allowed the production of large panes of glass, department stores were perhaps responsible for taking the art of window display to a higher level, using their large windows as stages, some of them as theatrical as a Broadway show. Today, color, props, and atmospheric lighting on many occasions arrogantly overshadow the merchandise, as visual merchandising extends beyond its role of supporting the wares and becomes an art form, creating a statement or provoking a reaction. Stores like London’s Harvey Nichols have collaborated with designers and artists to produce eye-catching schemes where the merchandise becomes part of an artistic work.

It is the department store, with its huge array of merchandise and vast amount of window space, that is the pioneer of the window display. A relatively recent phenomenon, it first began in France. Even there, however, for many years department stores existed only in the capital, Paris. It was Aristide Boucicaut who first had the idea of setting up this kind of store. He wanted to create a shop designed to sell all sorts of merchandise, but also wanted to attract crowds of people who could wander freely about in a little “town within the town.” In 1852 Boucicaut opened the world’s first department store: Le Bon Marché.

Bon Marché department store in Paris in the late nineteenth century offered an impressive shopping experience for its customers through the grandeur of its architecture.

A Selfridges window from 1920s London shows skill and imagination for its time, with its delicate display of handkerchiefs.

The 1960s saw the creation of ready-to-wear fashion for the mass market, and Mary Quant was one of the first designers, in 1959, to use the window of her London store as a showcase for her collections, as well as to promote social trends.

The concept of the department store then spread to the United States, where famous stores as we know them today first opened: Macy’s in New York in 1858, Marshall Field’s in Chicago in 1865, Bloomingdale’s in New York in 1872, and also Wanamaker’s in Philadelphia in 1876.

No one retailer or department store can possibly take the credit for producing the first eye-catching staged window display; however, we can certainly look to various individuals who helped set the standards for today’s visual merchandisers.

It was American retail entrepreneur Gordon Selfridge who had grand aspirations to bring the concept of the department store—and with it the language of visual merchandising—to Edwardian London. After leaving his post as managing director of the majestic Marshall Field’s department store in Chicago and emigrating to England, he arrived in London with grand designs to build a long-awaited premier, purpose-built, modern department store.

On March 15, 1909, Londoners witnessed the unveiling of Gordon Selfridge’s £400,000 (around $700,000) dream. Selfridges became the benchmark of British retailing. Its vast plate-glass windows were filled with the finest merchandise its proprietor had to offer. Selfridge also revolutionized the world of visual merchandising by leaving the window lights on at night, even when the store was closed, so that the public could still enjoy the presentations while returning home from the theater.

Selfridge also included a few innovations in-store for his customers—including a soda fountain for the sociable and a quiet room for the less so. He was never one to miss out on a promotional opportunity. When, in July 1909, Louis Blériot crash-landed his airplane in a field in Kent after flying across the English Channel, Selfridge had the plane packed on a train at 2 a.m. and on display the same morning at 10 a.m. Fifty thousand people queued to see it that day. By 1928, Selfridges had doubled in size to become the store we now know, due to the hype and success of Gordon Selfridge.

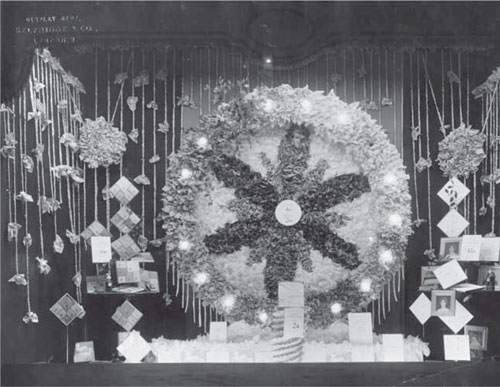

Maybe it is not the most innovative display by today’s standards, but Marshall Field’s window from the early 1900s caused a public reaction at the time in Chicago.

The coats on the mannequins in this 1950s window display at Printemps in Paris may look elegant, but the mannequins are rigid and not grouped to engage with each other.

The 1920s saw an explosion of creativity in the arts and fashion, which spilled over into the art of window display, and, once again, it was Paris that led the way. Frustrated that their canvases could only be seen in the homes of the rich and famous, many young artists in the city took their skills to the masses. Soon, the arcades of the capital were occupied with Art Deco-inspired themes, and fashion designers now found an innovative and exciting static runway on which to show their creations.

By the 1970s, window dressing had begun to reflect the spirit of the age. In this window from Printemps in Paris, the mannequins are displayed in tune with the times, with mirrored plinths suggesting the mirror-balls from the discos of the day.

The American fashion brand Banana Republic produces eye-catching window schemes incorporating interesting props, as well as a strong fashion statement, to make their windows both innovative and commercial.

The department stores of New York’s Fifth Avenue followed suit. In the 1930s, the surrealist artist Salvador Dalí can be credited with setting the American creative criteria in window display. He was approached to dress two windows for the Bonwit Teller store. Street art took on another dimension when he unveiled his “Narcissus” displays, but it was a step too far: his outrageous pastiches were removed after complaints. Yet Dalí’s lack of success did not deter other would-be artists from beginning their careers as window dressers. The artist Andy Warhol began his career in the stores of New York while still in college; Jasper Johns, James Rosenquist, and Robert Rauschenberg all worked as window dressers in the 1950s.

It was not only the big department stores that followed the new style of window dressing. As fashion shifted from the couture houses to the major streets and social trends developed, fashion designers worldwide began to make the most of their windows. Pierre Cardin, Mary Quant, and Vivienne Westwood are just a few who told the youth of yesteryear which social tribe they should belong to by dressing their windows to inspire.

Terence Conran was acutely aware of the shifting fashion trends. In 1964, he created a store to match those of the emerging fashion boutiques, but his differed in its type of product: furniture. Chelsea, London, was the epicenter of style and youth culture and Conran was quick to capitalize on this. His first store boasted whitewashed walls, creating a sense of space that came as a revelation to home-owners. Customers who visited his growing empire soon experienced spotlit ceilings, tiled floors, and cafés. Nowadays, Habitat still maintains its presence in Britain’s towns and cities, together with other stores such as Liberty and Harvey Nichols that paved the way for the retailers of today; in New York an equivalent is Barneys.

The development of technology in the 1990s and the birth of super-brands like Gucci and Prada saw the evolution of window displays into propaganda machines. With massive marketing budgets behind them, these larger brands were able to produce mass-marketing campaigns that featured the world’s most desirable faces and bodies. In the windows of fashion stores, the mannequins that had graciously modeled garments for decades became redundant and were often replaced by huge, glossy photographs of emerging catwalk supermodels. Runway shows from the world’s fashion capitals were projected on high-tech TV screens, and the clever use of lighting not only enhanced the product but also helped to create ambience and drama.

Thanks to the experiments and experience of the window dressers from yesteryear, today’s visual merchandisers have a lot of proven techniques with which to work. Visual merchandisers working in the proliferating fashion-store chains today, for example, are reintroducing the mannequin to the shop window, having acknowledged it to be a successful option for displaying the latest trends in a similar manner from store to store. The Spanish fashion store Zara, for example, employs traditional window-dressing techniques, its innovative window schemes and clever fashion styling placing its windows alongside those of the major luxury brands.

Now that retail brands have not only taken control of the foremost shopping streets in all major cities but have also infiltrated rural towns and villages, their innovative techniques in visual merchandising have also made an impact on their competitors. In the last decade, brands have pushed the boundaries of visual merchandising not just by creating in-store displays to drive sales and keep the customer inspired but also by introducing new techniques: DJs performing in urban clothing shops; contemporary eateries flanking fashion floors; books and magazines breaking out of their host departments; and fashion shows that can be viewed not only by the fashionistas but also by lunchtime shoppers.

Today, a brand might exist within its own store, but the store can also become a brand in its own right, populating its floor space with other brands, the idea being that together they will generate more sales. This is particularly apparent in the larger department stores like Selfridges, Printemps, and Macy’s. Either way, the visual merchandiser’s task is to communicate a fundamental message to the public through window displays and in-store visual merchandising.

In the twenty-first century, the latest challenge to the supremacy of the traditional store is the Internet. Shopping from home is not only easier but also price-competitive. Stores are under even more pressure to ensure that their customers return and spend, and it is the visual merchandiser who will be key to attracting and retaining their attention. Fortunately, shopping has always been a social activity, and the thrill of it will always be the major part of the consumer experience. Whether shoppers are out to discover an unexpected bargain, find an item sought for a long time, or meet up with friends while browsing, it is the job of the retailer to guarantee that they not only purchase but have a positive retail experience. With the help of good visual merchandising, this can easily be achieved.

In the larger department stores, men’s fashion collections such as Alexander McQueen, John Galliano, and Dior sit together in one area to create the men’s designer room. The design of the floor layout demonstrates carefully considered use of visual merchandising: note its cleverly positioned fixtures, clear signage, and the use of the window at the back of the cash desk, which creates a focal point for customers entering the department.