CHAPTER EIGHT

![]()

SUSTAINING

LUXURY

![]()

Considered consumption

and brands with substance

as the new indulgence

RETHINKING LUXURY

When LVMH announced plans in

2001 to develop its own environmental

charter and then signed onto

the United Nations Global Compact

two years later, it felt as though

someone was breaking ranks.

Until then, luxury had always put

itself above overhyped trends

and buzzwords. High-end brands did

not feel the need to participate

in the current dialogue because they

created their own dialogue. By signing

up for the UN initiative, LVMH

committed itself to adhere to

10 basic principles of human rights,

labour, environmental

protection and anti-corruption.

When LVMH began producing an annual environmental report, the move looked smart and, more than anything, the right thing to do. The company clearly saw its role as a global citizen and decided to take action. And it told everyone about it. LVMH embodies much of what we think a modern company should be: both environmentally conscious and open about its efforts.

Sustainability is here to stay. Companies are now embracing their responsibilities as global citizens and initiating change. By working to lower their environmental footprint, luxury marketers are finding support among customers. In 2012, PR house Edelman discovered that 61 per cent of consumers would opt for a brand with a good social-purpose track record when deciding between two products of equal price and quality. That is a steep jump from the low 40 percentiles in two previous annual surveys. And 63 per cent are willing to pay more for a brand that supports a good cause.

Becoming sustainable or even just shifting towards greener policies can be complex, sometimes requiring the complete revamp of manufacturing designs and supply chains. Still, demand for environmentally and labour-friendly products remains strong. Nearly half of all people surveyed in a worldwide National Geographic study were rated as having green consumption habits. At least a handful of luxury companies acknowledged this trend early and began adapting about a decade ago. Now, they are quite literally years ahead of the competition. Let them serve as pioneers and trailblazers and follow their lead. Ignoring the trend is perilous.

LVMH was not just a lone wolf. In 2004, Gucci began a voluntary process for social responsibility and received outside certification of its efforts three years later. In 2010, it not only introduced new fashion lines but also shipped redesigned packaging to its stores. It eliminated plastic laminated bags and paper, replacing them with recyclable materials. It has the Forest Stewardship Council certify that its paper sources are not from endangered forests and has even replaced polyester ribbons with renewable cotton. Its mannequins are made of recyclable materials. And, lately, it has been signing one environmental pact after another while releasing a string of environmentally friendly products. There are its Green Carpet Challenge handbags, which use leather from deforestation-free ranches in Brazil and are aligned with the Green Carpet charity launched by Livia Firth, the wife of actor Colin Firth. The handbags now even come with a detailed history of their donor cows’ life. The company also has sunglasses made of what it calls “liquid wood” – biodegradable and supposedly composed of wood fibre, resin and lignin polymer.

Then there is its Sustainable Soles line of footwear, which basically degrades better than traditional footwear. A big part of Gucci’s environmental consciousness is its two-pronged approach. It is helping to save the planet, and it is happy to let people know about it. It is difficult to read anything about sustainable luxury without running into the brand’s name. If you are putting in the effort to help the planet, let your customers know. “We have done a lot but there is still a long way to go. For this reason we keep increasing our investment in terms of commitment and resources,” says Rossella Ravagli, Gucci’s corporate social and environmental responsibility manager.

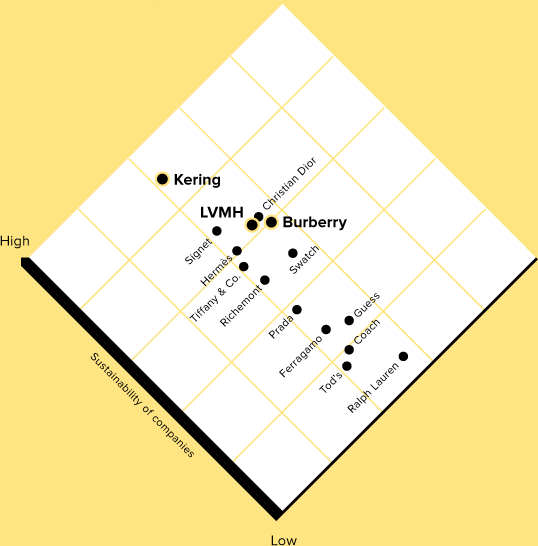

The efforts have even flowed upwards. In 2009, Gucci parent company Kering (formerly PPR) used its deep pockets and the public’s growing interest in Mother Earth for a worldwide marketing campaign that helped to increase the visibility of the luxury conglomerate and its brands while raising money for charity. The company financed showings of the film Home, which featured visuals of the earth and the way humans have altered it. The releases were timed with environmentally friendly product releases from Kering’s many brands, including Gucci. We include this as an example of how companies can leverage green issues not only to boost environmental awareness but also to attach their brands to the issue. An infographic on page 183 illustrates Kering’s environmental successes compared to its rivals. An important caveat: be sincere about your environmentally friendly intentions and actions and consumers will reward you; hide excessive emissions or labour abuses while claiming to be sustainability-conscious and you will be pilloried by consumers and the media. “Greenwashing” should not even be considered. You should be sincere about your efforts. The luxury fashion label Stella McCartney could be a role model. The successful “vegan” company does not use fur or leather for its products and tries to buy fabrics and other raw materials from sustainable sources. But it also admits that it is not always possible to use sustainable products to create luxury fashion, because current supply cannot keep up with heightened demand for organic and fairtrade fabric.

The Gucci passport

Prove you are making a difference: The Green Carpet Challenge passport certifies that the leather didn’t involve deforestation.

SUSTAINABILITY AS BUSINESS MODEL

Consumer demand for environmentally friendly products has done more than just push industry veterans to look at their supply chains, develop green solutions and find ways to show they are doing all they can to help the environment. The demand has also created opportunities for entirely new business ideas – the environment as innovation factor – such as Livia Firth’s Green Carpet Challenge, which pushes designers to incorporate sustainability into their high-end lines. Meanwhile, luxury companies should think about new product ideas, new production methods or even new business fields based on sustainability. This goes beyond concerns for the environment. Sustainable business practices also include ethical working conditions, fair-traded raw materials and long-term planning.

Loro Piana, the 200-year-old Italian cashmere producer, is enjoying strong success with a sustainable business model. The company has set up shop in Ulan Bator to monitor its wool production and make sure that it follows ethical animal husbandry rules among tribal herdsmen. Back in Italy, the company that mills the wool for use in clothes and interior furniture highlights its vertical integration as a means of controlling quality. Strictly organic? No, but deeply ethical and with a clear concern for both the environment and the bottom line. The company has leveraged a growing interest in animal welfare to support a brand image of complete excellence.

Although a complete corporate makeover as at Loro Piana is not always possible, other pioneers are creating entire companies to profit from the environmental boom. Germany’s Nanai is one example. Although salmon farming itself can be controversial, using more parts of the individual salmon raised on organic farms can only be seen as a step in the right direction. Nanai takes the skins left over from salmon production and uses a vegetable-based tanning process to cure them for a variety of uses that range from clothing to automotive interiors to furniture and even shoes. The company uses exclusively organic salmon farms and promotes the skins as a substitute for more exotic skins such as rays, snakes and crocodiles. Nanai takes its name from the Nanai people, who traditionally caught salmon in the Amur River in eastern Russia.

Sustainability has long been a key component of luxury

Many companies have launched eco-activities over the past decade.

Kering committed to producing environmentally friendly products group-wide, and introduced a code of ethics as well as green and social audits.

LVMH launched its environmental division in 1992, and made its supply chain transparent.

Burberry conducts programmes tracking its supply chain and has joined various ethical trading initiatives.

Source: Bank Sarasin

MADE TO LAST

To a certain extent, luxury has always been leaning towards sustainability. The entire premise of luxury is that products are made exceptionally well using the best materials. In short, luxury lasts. High-end products are the antithesis of the modern world’s throwaway culture. Watches were (and are) often purchased with heirs in mind – Patek Philippe points this out in most of its marketing materials and lists “heritage”, clearly defined as inheritance, as one of its 10 guiding values. Most luxury cars will be handed from one collector to the next for generations. Porsche is happy to proclaim that some 70 per cent of all the sports cars it has ever made are still on the road. A similar dynamic is at work with things like sailing yachts, jewellery and especially works of art. Reminding customers that what they are buying will be around for decades should be a cornerstone of sustainability communications for luxury companies.

BECOME TRANSPARENT

We think companies could also increase the transparency of their supply chains and manufacturing processes. If a product’s materials really are the best, then let us see where they are coming from. The best of the best should always be conscious of this and, as long as no company secrets are revealed, customers should know where the tiniest part of their newest watch originated. Remember that Gucci handbag with a complete history of the cow the leather came from? That is the kind of transparency we are talking about. “People read something in The New York Times about how a brand doesn’t produce everything in France or Italy anymore, which are the traditional countries for luxury production,” says former Hugo Boss designer Bruno Pieters, who recently launched his own Honest By brand. “They read the wallets or scarves are made somewhere else, but in terms of their perception it affects the whole brand. They think it is all made in China. It’s in the interest of luxury brands to be transparent about the production of their products.”

Transparency does not just have to relate to products. Companies should also be improving their business practices, aligning such things as energy use and construction to new norms with lower impact. Here, once again, companies should communicate their efforts to customers and media. These practices are not just good for public relations and marketing – they can also actually save money. “From a business perspective, our sustainability efforts not only help to build our brand equity – but save us money too,” says Chuck Bennett, former VP of Earth and Community Care at Aveda. “For example, energy conservation efforts at Aveda save over $540,000 in utility costs annually. Our business has grown five times over in the past 10 years, and we’re among the top five performing brands in the Estée Lauder portfolio. We are able to achieve all of this while pursuing a green agenda.” Sure, Aveda is not strictly a luxury company, but it is a solid illustration of where improving business practices can lead.

CREATE NEW GREEN PRODUCTS

Along with the rise of sustainable products, a handful of sustainable luxury fairs have popped up, most notably 1.618, which each year selects distinctive products it feels are sustainable and then highlights them at a trade fair in Paris as well as in its online catalogue. Browsing the publication from any year shows that designers are not reinventing the wheel, they are simply turning to greener suppliers or taking environmentally friendly twists on new products, not all of which are viable yet. One of the most high profile of these companies is luxury carmaker Tesla. Its whole mission is to create electric cars without the limitations of electric cars. Tesla is fully aware that its wealthy customers are the only ones who can now afford cars in the early stage of development, where R&D is most expensive. As is visible in the 1.618 catalogues, this is becoming the norm for many areas of luxury – there are even solar gliders and yachts alongside the usual bevy of clothes made from renewable resources. Companies need not shy away from the exorbitant sticker prices of producing green products – the innovations may prove to be beneficial themselves in the way of profits. Admittedly, your company better have some experience in innovation and technology here (like a car or computer maker) but prestige and profit can come not only from consumers but also from other manufacturers.

GET CERTIFIED

Consumers today are smarter and better informed than in the past. Few are willing to simply accept the fact that your company or suppliers are working with the environment in mind just because you tell them it is so. However, sustainability has expanded beyond environmental questions to also include labour practices, not only at your company, but also at those of your suppliers. Over the past decade, corporations around the world have become accustomed to preparing sustainability reports for investors and other stakeholders, who are just as sceptical as consumers. The trend is maturing to include the provision of audited sustainability reports, much in the way corporate governance or financial statements are audited by external accounting firms or other experts. Luxury companies might want to get in the habit of not only preparing similar reports for their owners but also volunteering information on the pedigrees of supposedly green suppliers or even offering total transparency of a product’s background.

This need for certification has led to an explosion in companies offering seals of approval, which may raise the question of who audits the auditors. But for now, the certification companies appear to be sparking adherence to some basic tenets of environmentalism and fair labour practices, which should be seen as positive by everyone. When looking for ways to certify green practices, companies do not have to hunt hard to find a certification agency for their particular niche. In fact, they may not have to do any searching at all – one of the world’s biggest standards agencies is the best place to start for any company. The International Organisation for Standardisation is familiar to any company that ever had to introduce accountability, whether for insurance purposes, for investors or just to improve management oversight. The agency, better known as ISO, is behind the most prevalent certification system in the world. ISO has not missed the exploding interest in environment-related certification and offers an entire family of standards that we think luxury companies might want to investigate.

ISO standards are the place for any company to start its environmental certification process – first, because of the agency’s deep experience in creating and establishing broad standards and, second, because certified adherence to ISO standards is such a universally recognisable signal. It simplifies the effort of communicating your company’s environmentally friendly actions. ISO has developed the 14000 family of environmental standards, the basis of which is the ISO 14001:2004 certification. Admittedly, certification titles could not be less sexy, but that makes them seem all the more sincere. The 14001 certification proves your company has a viable environmental management system. The important thing is to demonstrate that your company has created and is maintaining some form of environmental management. ISO then has other standards under the 14000 heading to establish the type of labelling to reflect a company’s green efforts, including reporting of greenhouse gases, specific aspects of product design and development, and environmentally friendly communications. Many luxury companies already include at least one ISO certification among their collection, underlining the necessity.

Other certifications could apply to whatever it is your company is offering. Most companies would help themselves by ensuring that any paper products (such as packaging) come from suppliers certified by the Forest Stewardship Council, which monitors forest-management practices. Tourism companies have a variety of certification opportunities, such as the Global Sustainable Tourism Council’s standards or the Luxury Eco-Certification Standard from Sustainable Travel International. Restaurants can also look for certification, for example from the Marine Stewardship Council, and luxury real-estate developers and resorts can get Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification for construction projects. Certification agencies are easy to find but must be vetted for relevance. The same caveats should be applied to a certification agency as to any business partner – how long they have been in business, references and even recommendations from industry peers. In any case, if your company is big enough, a compliance or even environmental officer placed high up in your organisation should already be actively looking for and applying for certifications. You do not have an environmental or corporate social responsibility director? This could boost the competitiveness of a company.

As stated earlier, sustainability today means more than just the environment. When consumers talk about sustainability, they also mean sustainable work practices, not just in developed nations but also in the cheap-labour countries. Most of today’s shoppers want a clear conscience when they purchase. Luxury companies should use their wide margins to offer consumers that clear conscience, and communicate their justification for having a clear conscience of their own. The SA8000 standard is perfect for this. Founded in 1997, the New York-based Social Accountability International (SAI) has created a way to certify companies based on the way they treat their employees as well as on how workers are treated along the supply chain. The organisation says it bases its standards on those developed and supported by the International Labour Organisation and the United Nations. Compliance should be simple for most luxury companies, and SAI says it keeps an eye out for all the usual labour issues including child labour, forced work, safety, self-determination and even management systems.

With wide margins and stratospheric expectations, there is little excuse for luxury not to be sustainable or at least making an effort to have a smaller environmental impact. Luxury companies should be using their prestige and high profiles to set an example for other brands. They already offer environmentally and socially conscious products, can easily adapt to a sustainable future, and even leverage those efforts to raise their profile and win new customers. Sustainability is much more than a marketing strategy.

INFLUENCER

Bruno Pieters of Honest By

Being stylish and green. For a long time it was an oxymoron. Clothing made from organic materials was “good” but seldom looked great, exuding more of a muesli vibe than serious glamour. But the high-fashion industry has evolved and there has been a shift in attitude towards offering luxury that rewards not only the consumer but the producer of the garment as well.

Bruno Pieters is one of the designers pushing this movement along. And he comes with a serious pedigree, having spent much of his career working for luxury labels, among them Hugo Boss and Delvaux, Europe’s oldest leather goods brand. Pieters credits a trip to India in 2011 with changing his outlook on fashion and how the garments we wear are produced. The experience affected him so profoundly that he decided to part from his own label and founded Honest By in early 2012, a brand for green fashion that is open about its production line and sold exclusively through its online store.

Vegan or organic?

Next to Pieters’ designs, Honest By offers a selection of other brands such as Calla and Maison des Talons, giving each designer the opportunity to share how and where their clothes are made. The unique selling point is complete transparency, delivered visually on the website in a way not unlike any successful luxury fashion brand. Consumers can not only choose among menswear, womenswear and accessories, but are given the option to pick from vegan, organic, recycled or skin-friendly from a selection of well-made, beautiful fashion. Besides, the company only uses green energy, has a carbon-neutral delivery scheme, works with fabric that is almost exclusively certified organic, and only uses recycled paper. It is an all-round concept rather than a marketing ploy, giving the customer the chance to contribute, as 20 per cent of the company’s profits are given to charity. And showing that it is after all possible simultaneously to care about things and wear fine garments.

“Explain what

you do, and explain

why you do it.”

An interview with Barbara Coignet, founder of 1.618 Sustainable Luxury, a Paris trade fair of sustainable luxury products that highlights both new and established brands.

How did you come up with the idea of starting a trade fair about sustainable luxury?

I worked in the fashion industry for 12 years as a PR and communications liaison for designers and artists. Around 2006, I started asking my clients: Where do your products come from? Are you interested in production that is ecologically sensible? Every single one of them gave me the same answer: We can’t afford to care about the environment or sustainability because we have to choose – either we are creative or we care about the planet. But I’m a curious person, and I wanted to show them that it’s possible to do both. So I started looking for examples, around me, online, in other countries.

What did you find?

The easiest to identify were hotels, because they are essentially lifestyle organisations and they have to care about the environment out of necessity but also because of social aspects. When I had my proof, and kept discovering other projects around the world, I decided to showcase companies that have understood, and demonstrate that it’s possible to combine creativity and sustainability. That showcase is the 1.618 fair. Sustainability is not just about ecology, it’s also based on innovation and creativity. You can see it in the car companies, hotel chains, cosmetics and fashion brands that we present. Each brand has to fill out a questionnaire before they enter, judged by a committee of experts. There’s a problem with greenwashing and we absolutely don’t want to give a platform to brands that don’t truly invest in the sustainability of their company.

![]()

Consumers from China and Brazil are only

just discovering luxury. For them,

luxury often means name, brand and power

of the brand. In those markets, they are

not so interested in questions of sustainability.

![]()

Is it mostly new brands, or do you also feature established brands?

Some brands are very new. When you are a small company with 12 people, it’s easier to decide to produce sustainably compared to changing the reality of big companies. In our first year, we had brands like Sony and Tesla Motors, who were already well-known to luxury consumers. We also featured less familiar companies like Esther DuPont. The year after, BMW joined. The selection is always between 30 and 40 brands, of which perhaps 20 per cent are well-known. The rest is new.

Executives from luxury brands often argue that luxury is sustainable definition. They only work with real craftsmen, the products last a long time and so on. Do you agree?

From a philosophical standpoint – yes. The reality is often different. When a brand produces 600 bags per day, how can it say that rarity is important? True luxury companies do care and make it the focus of their commitment, and when rarity is a main concern, it coincides with a sustainable definition of luxury. But the central objective for brands is often to increase quantity. When you really want to protect the environment and your resources, you accept that resources are limited and propose high prices. That’s often the difference between luxury and premium brands. Premium always wants to increase the quantity.

So the argument is true only for the very top of exclusive brands?

Resources are finite. We all know that. For true luxury companies this coincides with their storytelling, selling rare high-quality objects. Luxury used to be the privilege of those with money and power. In the last 20 years that has changed. Today we see mass-produced accessories, by definition not luxury, sold by luxury brands. On the other hand, take Hermès. It has always based its business model on selling rarity and that hasn’t changed. Hermès is an example of a luxury brand by definition and what I mean when I say that sustainability extends to social aspects. It’s keeping the know-how in its own country.

But is this not the case for every luxury brand?

Not all luxury brands, which are often owned by huge companies, can be exemplary in every field. In a way, that’s OK. Nobody can change everything across all aspects of a business. Both the Hermès product, which is handmade and which you have to wait for, and the mass-produced sunglasses can be considered luxury products. They just don’t derive from the same values.

H&M sells and advertises organic cotton, but most luxury boutiques don’t. Does the luxury customer even care for sustainability?

We looked into that in research we conducted with HEC University in Paris. If you ask consumers whether they care about sustainability when they buy a luxury product, only 35 per cent answered that they don’t care. That’s a lot. More or less the same percentage, 37 per cent, answered that they do care. And the rest don’t know. But what’s even more interesting is that 70 per cent declared that because of its price, luxury has to respect sustainability criteria, that it would be scandalous if they didn’t. So, while most consumers don’t see it as an extra incentive to buy a luxury product because it is green, most of them actually expect the brand to produce sustainably in the first place.

So the topic is relevant for luxury brands?

Absolutely. Just look at what happens when there’s a negative story in the press about the social aspects of a brand, or where the wood or diamonds originate from: consumers boycott the brand. And social media is an accelerating factor. Today, consumers want transparency. If they discover that a product is not sustainably produced, the brand has a huge problem. That’s because customers are actually the sponsors of those companies.

![]()

The consumer still accepts paying €30,000 for a handbag.

That has remained the same. What has changed is that

they’re asking questions now: Where does the leather come from?

Under which conditions was the bag made?

![]()

Are luxury brands even more vulnerable in this context than other brands?

Yes. The consumer still accepts paying €30,000 for a handbag. That has remained the same. What has changed is that they’re asking questions now: Where does the leather come from? Under which conditions was the bag made? It gives them considerable power to change the market.

Gucci now sells bags with a kind of passport documenting the origins of the leather.

Gucci belongs to Kering, previously PPR, and this group has become really involved with sustainability. It always depends on the CEO or president. When he or she embraces those ideas, as Kering’s François-Henri Pinault has done, they gain significance very quickly. Stella McCartney, which belongs to Kering, is a good example of a caring brand. The designer doesn’t use leather or fur at all. Apparently, Kering is also planning to change the entire process and supply chain at Gucci and make the brand very green.

You said that more and more customers are asking these questions. Is this happening all over the world?

Those questions are gaining significance very quickly in Europe, which we know both because we are based there and because we issue questionnaires in stores and in partnership with HEC University each year. Every year, new issues are gaining in importance, and consumers are becoming more informed. But, of course, when we speak about luxury, we can’t only speak about Europe, because the main business is generated in China today. Luxury is universal, even if brands come from Europe. Consumers from China and Brazil are only just discovering luxury. For them, luxury often means name, brand and power of the brand. They are not so interested in questions of sustainability, but that’s changing more quickly than here. In China they weren’t very attentive to such questions only three years ago. But now, they have the ability to address these issues, and have come to the realisation that they have to preserve their resources. So, some change is happening, and it will materialise more quickly than here in Europe.

As a consumer, if I am interested in buying sustainable, ecological products, what should I look out for when I enter a luxury shop? Should I look for certain certifications or certain labels?

Let’s look at Stella McCartney as an example. The brand’s labels tell the story of each product. This kind of true storytelling and transparency is important. A salesperson has to be able to answer questions about where the materials come from and where the product was made. Again, some companies are continuing to work in Bangladesh or in Turkey. They only finish the label in Italy to get the label “Made in Italy”. So, if you, as a customer, buy that product, you can’t be sure that it was actually entirely produced in Italy. Luxury brands have to be transparent. The problem is, the entire culture of luxury is based on being exemplary – at everything they do. They have trouble communicating that there are parts of their business that can be improved.

If you were to consult the CEO of a luxury brand, what would you recommend to him or her about this?

For fashion brands, the main issue is to increase visibility and gain control over the whole supply chain. Another issue is that, in the 21st century, you can’t say, “I have to use these bad fabrics, because I don’t have access to green materials”. Because, actually, you do. You have the power to create them.

You also mention authentic storytelling and transparent communication about where and how the products are made.

It’s quite simple. Just speak to your consumer. Look at social media. If you, as a brand, want to ask someone to be your friend on Facebook, speak to them as a friend. Explain what you do, and explain why you do it. We launched a guide where 40 brands tell their story – with video, with text, with interviews, with whatever they want – to show their consumers that their luxury car is not just a wonderful-looking product, but also what was challenging about making it. Everything will be easier when luxury brands stop being so afraid about what the media and the press will say about “greenwashing”. If they’re transparent, there won’t be any uncomfortable questions.