CHAPTER FOUR

![]()

IS

BLING

NO

LONGER

KING?

Logo luxury versus the rise of new values that are dividing the market

RETHINKING LUXURY

“The era of the jet set is over.”

It is a surprising statement coming

from a man who represents

one of the world’s most venerated

luxury brands. Patrick-Louis Vuitton,

the great- great-grandson of

Louis Vuitton, has been director of

special orders for his family’s company

for over 40 years, and oversees

the manufacturing of bespoke luggage.

His name is synonymous with prestige;

his services are some of the best

that money can buy. When customers

are looking for something even

more extravagant than the brand’s

regular top-shelf products,

Monsieur Vuitton is the man they call.

So what prompted Vuitton to make his daring statement about the jet set? It would seem to be an affront to his clientele. “There will always be people who want to travel elegantly,” he attests. “But business travellers are playing an increasingly bigger role. Among the customers who order bespoke luggage are people who travel 200 to 300 days out of the year.” In other words, his customers are changing. Before, they would spend money on gimmicky indulgences. Over the years, Patrick-Louis Vuitton has produced trunks to transport everything from Barbie dolls to crystal champagne glasses. Nowadays, his clients are investing in luggage that will not just look impressive, but also serve a practical purpose.

Vuitton receives around 400 special orders a year, and is at the centre of the luxury market. Any change first felt by his company is likely to spread across the rest of the industry. In fact, we believe that the world of luxury has experienced a seismic shift in consumer behaviour. This is evidenced by an appreciation of values beyond a product’s monetary worth. Consumers in mature markets are moving away from ostentatious displays of wealth towards a more understated form of spending. Examples are the popularity of brands like Bottega Veneta and Loro Piana, which famously do not have logos. Yet, they still let the consumer communicate something valuable: the appearance of cultured consumption. And although this change in attitude is most evident in established Western economies, it is becoming true for Asian consumers as well. Addressing it will be vital to the success of any luxury brand.

MOOD CHANGE

Less bling, more discretion. That was the message received by the elites from the financial crisis of 2008. When Wall Street collapsed, the self-proclaimed “Masters of the Universe” came down with it. These were bankers with almost unfathomable wealth, who surrounded themselves with status symbols to demonstrate their power. Men like the former Merrill Lynch CEO John Thain, who spent $1.2 million on remodelling an office. Or the executives of Citigroup, who thought it prudent to add another $50-million jet to their existing fleet, even as the bank was being bailed out by the US government. It seemed crass, greedy and out of touch with reality. And although the spending of the wealthy soon recovered to levels that preceded the crisis, a more sombre mood had replaced the frantic spending of the 1990s and early 2000s. Showing off was no longer seen as appropriate, either personally or socially.

DEVELOPING TASTES

Luxury purchases are emotional buys that have intangible values beyond their price. One result of the recession is that consumers want to express understatement, sophistication and thoughtfulness. For some of the most popular luxury brands, this development poses an interesting challenge. Companies have traditionally taken it for granted that they could sell customers anything, as long as it had an impressive name, a recognisable logo or was simply very, very expensive. Handbags, sports cars, watches – the bigger and shinier, the better. This habit of “conspicuous consumption” was first described by Thorstein Veblen in The Theory of the Leisure Class in 1899, in which the author argued that the rich use the accumulation of possessions to demonstrate their status in society. Veblen wrote, “The motive is emulation – the stimulus of an invidious comparison which prompts us to outdo those with whom we are in the habit of classing ourselves.” According to Veblen, consumption is viewed as a competition in which products are used to gain advantage in distinguishing oneself from one’s peers. However, what this theory does not take into account is that, as a person’s wealth grows and becomes more established, their tastes develop along with it. We have identified four stages of consumption that companies should consider as they are reaching out to clients.

Stage 1 : Ostentation

This mirrors what Veblen described in The Theory of the Leisure Class. When wealth is first accumulated, the consumer likes to demonstrate financial prowess by buying and displaying symbols of their status.

Stage 2: Differentiation

As consumers become accustomed to their status, they develop a sense of awareness. This helps them make more informed choices and demand more quality and elegance.

Stage 3: Knowledgeability

A class of informed consumers who see themselves more as collectors. They distinguish between products as they live out their personal passions and seek pleasure.

Stage 4: Meaningfulness

In this final stage, consumers demand products that will bring personal fulfilment, engage them in immaterial ways and satisfy a sense of experience.

Of these four stages, the last one offers an opportunity for luxury brands to bind customers in the long term. Instead of aiming for the throwaway success of a quickly sold lifestyle product, this could be a goal to consider. But how do you best engage customers’ longing for refinement while providing them with an opportunity to demonstrate their expertise? David Brooks has some answers. In his 2000 book, Bobos in Paradise, The New York Times columnist first identified an emerging class of spenders, a composite of “bohemian” and “bourgeois”. Brooks writes, “A new set of codes organises the consumption patterns of the educated class, encouraging some kinds of spending, which are deemed virtuous, and discouraging others that seem vulgar or elitist.” Furthermore, “The members of the educated-class elite feel free to invest huge amounts of capital in things that are categorised as needs, but it is not acceptable to spend on mere wants […] A person who follows these precepts can dispose up to $4 million or $5 million annually in a manner that demonstrates how little he or she cares about material things.” It is at once amusing and revealing when Brooks determines that, for the Bobo, it is laudable to spend a small fortune on a road bike for exercise, but frowned upon to own a powerboat. A jacuzzi is considered too showy, but a slate shower stall is an investment in everyday pleasure. Spending hundreds on caviar? Vulgar. But you may spend the same amount on top-of-the-line garden mulch.

STEALTH WEALTH

What the examples above have in common is visibility. Or rather, their invisibility. Instead of proving something to the outside world, they satisfy an inner need. No one will see an exquisite piece of art hanging in the living room except people invited into the owner’s private home. A meal made with imported gourmet salt from Bolivia will be admired by only a handful of dinner guests. Of course, these products are still tokens of status. But they matter only to a select group of insiders. These luxuries are not seen by the general masses, and if they are, do not mean much to them. As a result, they are not open to criticism. They satisfy a very private vanity. Research into the purchasing behaviour of luxury consumers confirms as much. Of those questioned in one study, less than half answered that they “buy products for image reasons”. Yet 87 per cent said they were most interested in “the very best quality”. This is a high number, even if we take into account that respondents often demonstrate a need for social desirability in such surveys. We call wealth that stays undetected by the general public “stealth wealth”, and it is something that could provide good opportunities to luxury companies. After all, they stand for attention to detail, craftsmanship and the kind of excellence demanded by customers who want to buy something that’s more than a mere product.

TELLING STORIES

In the previous chapter, we mentioned Hermès as an example of a company taking new initiatives in the Asian market. What the brand has traditionally done very well is to make sure the product is worthy of its logo – in other words, valuing craftsmanship, even when this means going out of the way to find artists whose vision is appropriate for the brand. The famous Hermès scarf was first created in 1937. Some of the most popular designs the company has used are by Kermit Oliver, who then Hermès CEO Jean-Louis Dumas discovered while travelling in the United States in the 1980s. Dumas was taken by Oliver’s rich depiction of native flora and fauna. The painter has since produced some of the bestselling designs for Hermès. The coup? Kermit Oliver was not an established artist, but a postal worker from Texas. Here we have a precious material combined with a long history, excellent craftsmanship and the triumph of talent over obscurity. Women like Jackie Onassis, Grace Kelly and Audrey Hepburn, who were the epitome of sophisticated style, all wore Hermès silk scarves. The result is that the brand has had a bestseller for decades.

This kind of brand storytelling captivates customers. Cultured consumers dislike aggressive marketing as much as ostentation itself. If companies want to keep selling to them, they need to find more subtle means of communication. Some companies have already started moving away from brash advertising. Again, take Hermès. The product is the focus of the company’s advertising campaigns. They have never used celebrities in media advertising, something that sets them apart from competitors. Another company that has successfully harnessed subtlety is German retailer Manufactum. Under the banner “The good things in life still exist”, the company offers handmade and expertly crafted products, often locally sourced and with an appreciation for history. The nostalgia comes with a large price tag, but customers are happy to pay for it. At Manufactum you can find lamps from England that were once used on the ships of the Royal Navy. Or the Danish “Colonial Chair”, made from cherry wood in the same cabinetmaker’s workshop where the first one was made in 1949. Manufactum also has re-editioned scents from Paul Poiret, the first Parisian couturier to create his own line of perfumes. Manufactum customers are made to feel as though they are not buying a product, but maintaining a heritage. Then, of course, there are the brands that do not advertise at all. Not on paper at least. Their best advertisements are word of mouth and longevity. Prime examples are the tailors in London’s Savile Row. Anderson & Sheppard, for instance, can count on their customers to return only because they offer the kind of attention and impeccable work that make the price of a handmade suit seem worth it. And you have to look for their label, discreetly stitched on the inside pocket.

Quality, history and authenticity. Besides bespoke clothing, no other segment of the luxury industry manifests all three better than watchmakers. Patek Philippe is already using them to strengthen its position in the market. “You never actually own a Patek Philippe. You merely take care of it for the next generation,” says the advertising campaign alongside a picture of a father and son. In another ad, a mother and daughter are shown with the tagline, “Something truly precious holds its beauty forever”. These slogans satisfy a desire for meaningfulness, even if they seem to be clichés. They also legitimise the purchase. Customers do not just do something for themselves by purchasing a watch, but are also thinking of their offspring. Having non-egotistical motives is something that appeals to modern consumers. Infographics on pages 96 and 98 better illustrate consumer buying motivation.

Consumer development

Tastes change over time. Meaningful consumption dominates mature markets while ostentation rules in emerging markets.

GROWING SOPHISTICATION

It would be easy to assume that the emerging power players are still in the ostentation stage of the consumption cycle. After all, they have only experienced wealth in recent years and are drawn to the flash of popular brands. However, the fast growth of the market outlined in the chapter “East is the New West” has accelerated the sophistication of the emerging market.

Wealthy Chinese consumers are swiftly developing a taste for refinement. In 2012, two-thirds of Chinese consumers said they preferred luxury items that were understated and low-key. In 2010, it was only half. Similarly, more than one-half of shoppers felt it in bad taste to show off luxury goods in 2012, one-third more than in 2010. This is now equal to the statistics from Japan. What is intriguing about this is that Japanese consumers have been exposed to luxury for much longer. Markets develop at different speeds. Something else for companies to consider is that while there is a truth to every cliché, that truth is never the whole story.

FULFILLING ASPIRATIONS

With the different developments at play, it will be interesting to observe how companies bridge the divide between the newly moneyed and the established wealthy without losing customers. There is something they should keep in mind as they attempt to do so. As an expert of the luxury field once said, “If it’s not credible to an expert, it’s not aspirational to the novice.” As luxury becomes more widely available worldwide and to different classes and ages of consumers (a subject we will address in depth in our following chapter), the elite will always be ready to pay for even more distinction. The person buying a Porsche key ring is most likely not the same person who buys a Porsche. Someone who wears Chanel sunglasses does not necessarily have access to the world of made-to-measure Chanel fashions. For now, it is key to remember that true luxury often lies in limitation. Limited editions and unique products have proven successful for brands as varied as Dries Van Noten, which let shoppers design their own dress in a one-time-only event, or Montblanc, which offers customers the chance to create their own writing instrument with their designers. Similarly, limitation is key to the success of The Row, a fashion label created by Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen. The person walking down the street behind an owner of an alligator-skin backpack might mistake it for just another leather bag. But the person wearing it will know that it cost over $39,000, and that they are one of a few people on the planet who have one. The Row’s backpack sold out almost immediately after it hit the shelves of high-class department stores.

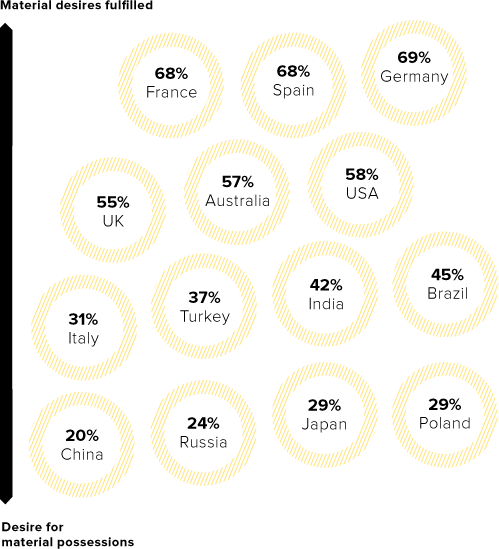

How much more do I need?

The basis for luxury shopping decisions differs a lot around the world. While Germans feel they have many material desires fulfilled, the Chinese would still like to have more stuff.

Source: World Bank

Looking beyond outward appearances, these customers also want to show that they can afford the kind of luxury that goes deeper. Yes, they could afford a sports car that costs half a million. But they would rather spend it on solar panels to heat their outdoor pool. Investing in sustainable luxuries, products that will make the buyer feel good, and do good at the same time, is a fairly recent development that deserves extensive analysis. We look at this in chapter eight. For now, we can establish that less on the outside represents greater value for modern luxury shoppers. This is good news for the brands trying to secure their commitment.

CASE STUDY

How understatement works

for Victoria Beckham

Everything about it was bling. A pop star marries a top-money professional football player. The duo jet-sets around the world, looking as good in paparazzi photos as in advertising campaigns. David and Victoria Beckham.

No wonder someone eventually asked Victoria to put her name on a clothing line. Even if she needed support to design, any marketer knows she is a moneymaker. Her role as a mother and her openly discussed marital problems endeared her to women of all ages.

But many were surprised when the line was launched in 2008. They were even more surprised by its success. The clothes feature the same simple look which is her signature on the stairs of a private jet, leaving a private club or even shopping with the kids.

Victoria Beckham boutiques are intentionally low-key. Often you cannot see the name until you peer inside the door. The locations are understated too: Bahrain, Australia, Canada, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belgium and China. Her first London outlet was only expected to appear in 2013 and her online presence began in the same year.

Beckham said she worked for three years to get the website to reflect the look of her stores. Her new website also acknowledges the impact of online shopping. Her Icon brand is only available online, and she includes Instagram and other intimate snaps of her life to pique interest. We discuss this further in chapter five.

The brand’s success is anything but low-key and recently landed her on BBC Radio 4’s list of the most influential women in Britain.

The Victoria Beckham look

The former Spice Girl has created a brand that draws on subdued design and simple lines, as displayed by this model.

“Increasing education brings more customers.”

An interview with Anders Thomas, CEO of Porzellan Manufaktur Nymphenburg, which has been making porcelain at the same site in Germany since the 18th century.

Is luxury consumption moving in the direction of inner values, and as a result, is it becoming increasingly less conspicuous?

We are seeing a trend that people want to buy quality that has authenticity, and this is a contradiction to so-called “bling-bling” luxury. In this respect, you gain a certain amount of authenticity with craftsmanship, real value-creation. You produce a luxury item that sets itself apart from industrially manufactured products that with lots of marketing can get tagged as being luxury. Customers today are more selective and are taking a look at the true value behind a product.

Why is that?

I think it’s because many customers who have the financial means are looking for a product that their neighbours can’t buy, because it’s just not available on the mass market. You would like to own a product that, by the choice of the brand, is signalling connoisseurship.

Why are Nymphenburg products an example of this?

Anyone who buys our products has this connoisseurship. With porcelain, we are part of the third pillar of the luxury market. The first is made up of products you wear: watches, jewellery, clothing, sunglasses, shoes or handbags. The second is products which are also visible to everyone. Your car, home, maybe a boat. But I only let others see the third pillar when I invite them home for a dinner and take out my tableware. The external impact we have as a luxury product is very low-key, but at the same time we are especially important. Someone who is familiar with porcelain can immediately see whether it’s Nymphenburg or another brand. Every métier has its connoisseurs and I believe porcelain is experiencing a renaissance among them right now.

When referring to the maturity of luxury markets, we speak of four stages of luxury. The first stage involves “ownership orientation”, then comes “differentiation”, then “knowlegeability” and finally “meaningfulness”. Where do you see yourself here with your products?

Probably somewhere between three and four. Someone who buys a service from us for €200,000 usually likes to express their personal wishes to us. Anything from their initials to elaborately crafted portraits of family members. Or drawings of the 15 manor houses they own. We’re already way beyond “differentiation” here, in places where people are searching for meaning. And this is where the trend is headed in the luxury sector: towards values and culture, in this case the culture of dining. People now say, “I want a leather bag that was hand-sewn by one craftsman who completed all the steps himself, starting with the initial cutting to the finished bag.” At the same time I’m buying a story, an emotion, a personal connection, which is reflected in the product. I become part of it.

Are you in international markets that place more emphasis on status, and less active in developing markets?

This has a lot to do with education. Our customers are more versed in history and craftsmanship than average customers. This type of customer can be found in every market. We have Asian, Russian, Arab and American customers. And across the board, they all place orders at the highest level. Of course their preferences slightly vary. One might like more opulence and gold. Another, a little more red. Still another likes things a bit more classic or minimal. But basically, our customers always have the same standards for the product, art and design.

![]()

Customers who have the financial means are looking for a product that their neighbours can’t buy, because it’s just not available on the mass market. You would like to own a product that, by the choice of the brand, is signalling connoisseurship.

![]()

But what’s it like in China, where the market is still in a relatively early stage of development. Isn’t it true that customers who have more refined tastes and knowledge are more likely to find their way to your products?

That’s true. I gain more customers the more I educate them. At the same time, customers in China are searching for authenticity, as it’s lived in Europe. So I see no need of a different marketing strategy than in other regions, except for adapting the language.

On your website, there is an exclusive login area. Can you tell us what’s behind that?

This is the area dedicated to our project business, in other words, bespoke products. If you want to choose a very specific shade of blue for your villa, for example, we will develop it for you. Or, for when we design a new decor for a yacht. Customers can log in there and take a look at how their project is coming along. From the development stage through to production in the lathe shop, moulding shop and so on.

Is this an innovative way of creating loyal customers through the use of digital technology, something which wouldn’t have been done before? Or is this something that was always in place, only now it’s a different platform?

Previously, we had local customers, now we are increasingly more international. We sold tableware to China 40 years ago, but back then it was most likely a service from our classic repertoire. Today, I’m selling tableware in China which is tailored to the needs of our customers. This is why I need to communicate with them. And I do it online so they can observe the product’s course and also see its development. From start to finish, they’ll receive uploaded photos from our workshops documenting the course of the production. If they don’t have the time to visit our factory, that is.

![]()

I gain more customers the more I educate them. At the same time, customers in China are searching for authenticity, as it’s lived in Europe. So I see no need of a different marketing strategy than in other regions, except for adapting the language.

![]()

![]()

They don’t have to have the feeling they’re something special. They are special because they value the finer things in life.

![]()

That sounds quite technical. Isn’t there also an emotional aspect? I’ll feel like I’m getting special treatment because I have access to a closed area that doesn’t allow just anyone in?

This is exactly why these customers don’t buy other products which are visible. They want custom-made, unique pieces. That’s why they don’t want what is being created made public. Later on it will be presented to their friends and acquaintances. They don’t have to have the feeling they’re something special. They are special, because they value the finer things in life without having to flaunt it in public.

In your opinion, how has the luxury market changed over the past five years, and what can we expect in the next five?

Customers are becoming more established and want to pass on the story of the products they’re buying. That’s why they’re looking for something special. The brands of the big luxury companies that open up shops and offer the same products with different pricing in every place where money is there to be spent, they are the ones who are going to lose their allure.

Because they’re too visible, too accessible?

There’s over-saturation going on. Either I have to artificially make the product scarce, like the Kelly bag, where I have to wait three years before I can finally get one in red. But apart from that, these products are ultimately interchangeable. I think the trend is heading towards individualisation. I see that very strongly with us. If I went to the Kruger National Park and photographed 25 animals, then I’m going to like to have them painted on 25 different plates and also my wife should be everywhere in the background and my kid or my dog, or anyone who was there with me. I want to tell a story. The higher-price mass market will probably still hold up, only because there are enough customers in the pipeline. We’re seven billion people right now, in 2020 we’ll add on a billion more. 2 to 5 per cent of them will most likely be able to afford luxury products, eventually.

![]()

Customers are becoming more established and want to pass on the story of the products they’re buying. That’s why they’re looking for something special.

![]()