CHAPTER NINE

![]()

CAPTIVATING

LUXURY

CONSUMERS

![]()

Creating loyal customer

relationships in a climate of declining

brand commitment

RETHINKING LUXURY

Loyalty programmes often fail –

either conceptually or in generating

a profit. This is as true for

luxury brands as it is for brands

in general. From our perspective,

the main points of discussion here are

mission, scope, the application

of knowledge about customers, staff

and expectations of technology.

It sounds easy, but luxury brands should

not underestimate the task

of moving into loyalty programmes.

But first, let’s consider some context. More and more brands are trying to escape the middle- and even premium-market squeeze by approaching the luxury segment. More and more options are open to more affluent customers around the world, both physically and digitally. More and more touchpoints and technologies are available to connect with target groups. More and more loyalty programmes court customer acceptance. More and more luxury brands are operated by publicly listed companies which need to announce positive growth figures and optimistic outlooks – often diluting the brand by offering entry-level products for broader groups of less sophisticated shoppers.

Objective differences in product quality are diminishing in many categories and intangibles are becoming increasingly important for brand preference. Everybody does storytelling. And Generations Y and Z are showing less loyalty than their parents or grandparents. In addition, some particulars of the luxury market must be taken into account. Luxury lives from elitism, exclusivity, limited access for a chosen few, a strong foundation in myth (founder, owner, heritage, innovators, testimonials, materials) as much as it does from superior products and services, brand experiences or storytelling.

The idea of customer loyalty is often reduced to behaviour measured in terms of repurchase (that is, retention) and cross- or up-selling within the luxury brand portfolio. The core of standard programmes orientated around repurchase (or more-purchase) is knowing the value of individual customers. Typically, such programmes differentiate service and reward levels among A, B and C customers (gold, silver, bronze) by how much you spend. More sophisticated approaches either go for more customer groups or apply algorithms that add the customer’s future value to the equation and cluster the customer base around “customer lifetime value”. Developing, implementing and, especially, steadily earning money from such programmes is difficult.

“You need to be trustworthy. You need to be caring. That is very hard to do but that is the differentiator for Zappos, for the Apple stores, for Nordstrom people and for Ritz-Carlton people,” says Luxury Institute CEO Milton Pedraza. “You can measure it in customer retention and you can measure it in customer referrals.” Although Pedraza is talking more about premium brands, trust and caring are tickets of entry for luxury brands, too. And by bringing in customer referrals, it introduces the second dimension of loyalty: the attitudinal.

Attitudinal loyalty can even be exhibited by brand evangelists and ambassadors. And despite them being of little direct monetary value to a brand, they can be valuable multiplicators (bloggers, newsgroup administrators, community drivers) and thus affect the bottom line. While traditional loyalty programmes have been engineered around behavioural loyalty, more state-of-the art approaches also take attitudinal loyalty into account. This is driven by the rising importance of communication, interaction and communities in the digital sphere, as well as by the growing importance of mobile digital devices (smartphones, tablets) in the luxury customer’s life.

LUXURY SHOPPERS AREN’T CLONES

The preconception is that luxury-brand shoppers are a relatively homogeneous target group with a somewhat traditional, Eurocentric value set. In reality there always have been significant differences between various clusters in the luxury market – old money versus new, young customers versus old, men versus women, investment versus consumption.

This is why brands as diverse as Lamborghini and Rolls-Royce, Brioni and Gucci, Bulgari and Stein, Bordeaux and Riesling wines have all prospered in their particular niches. Nowadays, the diversity is multiplying by cultures (Europe, United States, China, Latin America), marketplaces (digital and non-digital, brand-owned spaces and multi-brand spaces), affinity to technology (smartphones, tablets, 2D versus 3D), new players in the luxury market and, not least, differing privacy expectations (offering testimonials for a brand versus staying anonymous).

If one thing is obvious from the above, it is that there is no such creature as the one homogeneous luxury shopper around the globe. You cannot even trust Chinese or American or Brazilian luxury shoppers to value the same things when travelling abroad that they love at home. In short, you cannot treat every brand evangelist or shopper the same way, nor should you always treat the same individual the same way. But like many other customer groups, these different and volatile luxury shoppers do have and often explicitly look for relationships with their top-end brands.

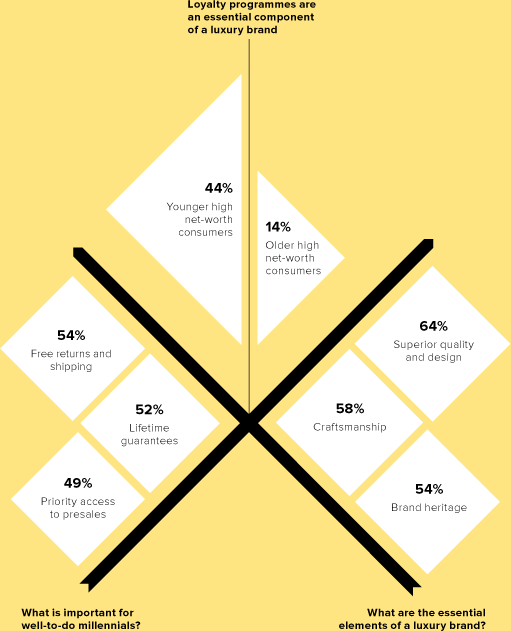

Making them feel wanted

What matters most to today’s luxury consumers.

Source: Luxury Institute

LET’S GET PERSONAL

Some decades ago, and with rather localised luxury marketplaces, craftsmen, retailers or hoteliers and concierges knew all the details of their individual customers and how to nurture loyalty from initial purchases. Especially in the bricks-and-mortar part of the business, this still holds true today. “The competitive advantage is customer culture, expressed by customer-centric human beings who out-behave the competition,” says Pedraza.

Companies must ensure that their staff are their own best brand ambassadors. People on the payroll need to be big fans of the products they are selling. If they are loyal to their employer and passionate about the products or services they represent, then it will be easy and authentic to pique the interest of anyone who walks into the store.

Although premium rather than luxury, carmaker Audi is a great example. The company recently discovered it was able to boost US sales by focusing on employees, rather than customers. Audi based the dealership programme around the German word “Kundenbegeisterung”, which we could translate as “inspiring customer delight”. It then invited more than 10,000 dealership personnel to immersion events around the United States to teach them more about the company and how to engage with customers, and also held special workshops to reinforce the principles taught during the events. The whole thing was also wrapped up in a web-based academy for anyone who could not attend the real-time events.

The result? The company’s strong US sales are supporting above-average sales growth. “Our goal was to redefine the customer experience, but first we had to win over the hearts and minds of our employees. We had to redefine the employee experience before we redefined our customer experience,” says Jeri Ward, director of customer experience at Audi of America. Audi’s customer loyalty in the United States has also risen more than 7 percent since 2009.

We like Audi’s success here, although we know how difficult it is in times of increasing financial pressure, growing expectations of the staff and decreasing loyalty to employers to deliver consistently in this area. On the other side of the coin, one negative experience with a luxury brand’s core retail staff can instantly kill a long-lasting relationship with a luxury shopper. After all, there are plenty of brand alternatives where he or she can expect to be professionally served as a valued customer. So, actively managing every member of sales staff who deals with a luxury brand or service should prove profitable.

The importance of hardware and software for managing loyalty is growing. This is driven by the global reach that luxury brands have today, the global mobility of luxury shoppers, the ubiquity of digital customer information in the 24/7 marketplaces and the ever-decreasing costs of data storage. Innumerable technical solutions, service providers, data-processing and/or analytical companies as well as loyalty process engineers and others are all trying to live from this development. But at the same time, reports of loyalty programmes that either could not be implemented or have never delivered a positive return on investment are on the increase. Why is that?

Robbie Williams once sang, “You can’t manufacture a miracle”. Well, you definitely can’t only by applying technologies, processes and reward schemes developed for the mass or premium markets.

For the forseeable future and with most luxury shoppers, personal interaction and the enjoyment of personalised treatment will remain vital. This is regardless of the fact that most luxury shoppers will be early adopters of the latest technologies. All the technology used for gathering, storing, analysing and deploying information about the customers of luxury brands should improve their personal brand experience rather than replace personal interaction. Being human and personal in that way, companies can create much deeper relationships with their customers and better tailor marketing activities to their particular luxury shoppers or attitudinal loyalists. Again, it is not rocket science, but at least one study shows that about half of all luxury companies do not take the time to personalise their communications. Loyal shoppers do not pay much attention to advertising and react little to a press release, but a handwritten note or invitation can provide the spark that gets them into the store. A personal touch in a hotel suite – a bottle of a customer’s preferred water, chocolates or champagne in a branded wine cooler – can provide a competitive edge that a rival might have forgotten. To create loyalty, companies must show that they have been paying attention on every single occasion when they interact with their customers.

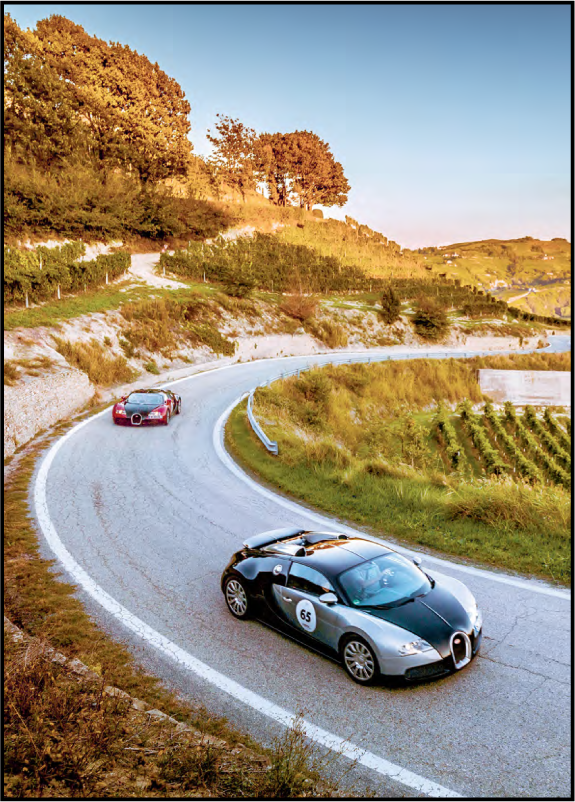

Driving with friends

Bugatti offers buyers exclusive tours through northern Italy. They are exceptional experiences which increase the bond between participants and the brand.

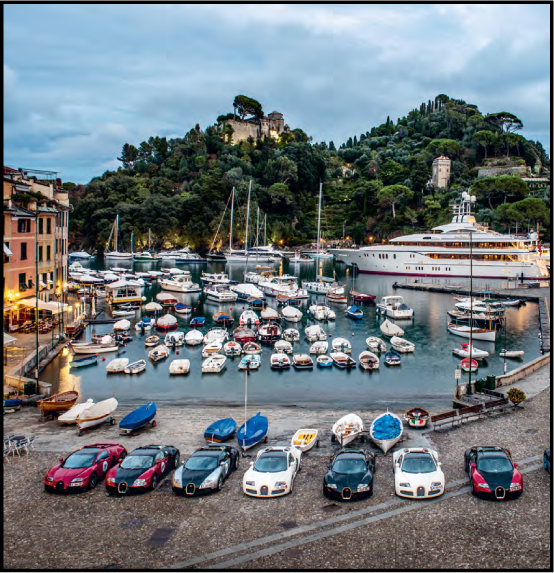

Living the brand

Bugatti has its own take on luxury. The tour communicates this by taking clients to the places in Italy where luxury lives, creating an unforgettable experience.

Do the bonus points and bonus miles in reward programmes satisfy this expectation of luxury customers? Or concepts that have spread to credit cards and now to special bonus retailing programmes that bundle together various chains hoping to profit from the loyalty and marketing intelligence behind the programmes? “Recognition of their loyalty through reward concepts or crediting your best customers with a higher status will encourage word-of-mouth recommendations which are hard to obtain and extremely valuable,” says Richard Dixon, customer marketing director at London customer relationship consultancy Black Sun. The same is basically true for attitudinal loyalists who, for whatever reason, praise the brand without buying its products.

THE TECHNOLOGY OF LOYALTY

In the globalized 24/7 luxury brand marketplaces of today, technology is vital for distinguishing those attitudinal and/or behavioural loyalists with whom a particular brand wants to be connected from those it needs for its financial health. Additional technology is able to cluster A, B and C customers by projected customer lifetime value. Similar technology can either provide information about the service level specified for each individual customer to the staff who personally deal with them, or deliver the individualised loyalty reward directly to the customer. Different perks can be offered at different levels, whether an all-expenses paid trip to Berlin Fashion Week or the opportunity to buy tickets for an exclusive company event during Ascot. The important thing is not to offer trinkets or token gestures, but something with real value. But what is of real value differs according to culture, geography, age, gender and many other criteria. To be successful, a loyalty programme must strike a balance. A balance between being too broad to be useful for the customer (though easy for the brand owner to manage), and of being extremely individualised (but too complex to be managed profitably). With all the possibilities of scenario planning, A/B testing, real-time feedback or automated orders, only technology allows a company to walk this fine line. But at the same time it is vital to acknowledge that no technological solution will improve any kind of loyalty or provide a positive return on investment without humans...

– understanding luxury brand customer experiences and customer journeys

– understanding the business cases for individualised loyalty programmes with different service levels/reward programmes for differently valuable customers or attitudinal loyalists

– knowing about the information needed to feed the technology

– knowing about the sweet spots to be addressed or supported by the technology

– being capable of setting up a technological platform that can grow and change along with ever-changing luxury customers

– being capable of extracting the nuggets from the continuous and quite likely continuously growing stream of information.

Technology-based loyalty programmes ensure that it is not only individuals within the luxury brand who know the whims of customers, but also the company. Companies can bundle the information gathered from different areas – online and in-store, for instance – and even geographies. Who buys what, where? And who is saying or writing what about my brand? This information should then be used not only to target specific customers but also to hone marketing activities across all aspects of the customer journey. As we noted in chapter three, Chinese consumers prefer to make their first buy at home but then splurge when abroad. Companies would do well to know when the shopper who has bought from the company in Shanghai is ready to spend his or her money in London. Thus, the true benefit of technology-based loyalty programmes comes from more efficiently derived, more effectively deployed and more profitable customer satisfaction, leveraging superior customer understanding based on continuously updated data.

BIG DATA OR SMALL?

Do the chosen few attitudinal and behavioural loyalists of a luxury brand really create “big data”? Or is big data required to manage relations with luxury brand customers most profitably? Or would sensitive, high-value luxury brand customers and ambassadors really appreciate being continuously X-rayed by luxury brand owners deploying big data techniques? The amount of data gathered related to luxury brands is tiny compared to the extraordinary volumes of demographic, economic and commercial information analysed by big data companies and their software. But nevertheless, it is more than enough to help predict the lifespan and value of the relationship between loyal customers and a luxury product marketer.

Companies should rely on this information to guide their programmes. Long-term customers deserve more lavish rewards than new customers. They have given more to a company and are likely strong ambassadors. Many companies are already gathering at least some of this information. We would remind them to take advantage of it systematically, possibly leveraging the information to benefit the customer in the form of more tailored, and thus more valuable, rewards. The information should be used to create detailed profiles that permit hyper-personalised service and special offers that will help expand loyalty. If customers experience how your knowledge of them improves the tangible and intangible benefits that accompany your luxury brand, it will deepen and stabilise the relationship. We have previously mentioned the hotel that knows if a customer usually brings a dog and then has a personalised water bowl waiting in the room. This is the kind of information that should be used. That customer will stay with the hotel because they know their dog will be as well looked after. This is about caring and experiencing the feeling of being treated individually as a truly valuable customer. But does this really require big data?

A contemporary and future-proof loyalty programme should be tailored around selectively chosen information relevant for dealing with the small elite that shops in the luxury marketplace, rather than around what is typically understood as big data – broad statistical information – aimed at finding out what customers are buying and why. The latter might be an appropriate and profitable tool for mainstream or even premium brands. Everybody who has done market research with brands from these three different spheres knows how much the difficulties in recruiting and costs per interview are increased by moving from mainstream to premium to luxury, from masses to many to very few. Similarly, the costs of data generation for big data projects can exponentially increase from mass to luxury markets.

If companies opt for public rewards programmes, linking up with partners can boost their attractiveness, increase their esteem and broaden the intelligence collected. The Ritz-Carlton only recently introduced its own rewards programme and already has a network of partners that includes department stores Bergdorf Goodman and Neiman Marcus, as well as National Geographic’s luxury tour arm. Customers can even gain points by staying at the hotels of its parent company, Marriott International. The programme has also introduced several levels of membership depending on how much customers spend – the biggest wallets obviously ascend to platinum status and points can also be spent at partner airlines. Judge for yourself whether this example from the premium brand arena can serve as a blueprint for a more sophisticated, individualised and upmarket luxury brand.

For us, more important than big data is that loyalty programmes are flexible and open enough to learn and adapt as a company discovers more about those who are spending money on its products or acting as brand ambassadors. And again, the humans dealing with (big) data or the technologies used to generate and analyse information, and using the insights they derive from it to increase luxury customer delight, are at least as important to your loyalty programme’s success or failure as all the technology behind it.

LEVERAGING COMMUNITY

For both behavioural and attitudinal loyalists of luxury brands, community is essential. Even far-above-averagely powerful, affluent and influential luxury brand shoppers want to belong to a particular cohort. In addition, they need exchange with peers and brands to fuel their self-image. There are many traditional community approaches, formal or informal, that luxury brand owners can leverage. These include physical gatherings in places like Saint Tropez, Aspen, Punta del Este, Sylt or Saint Moritz; sport events such as golf tournaments, ocean races and old-timer rallies; and alumni meetings of particular schools, universities or businesses. Much of the organisation of such events has already moved into the social web – most of it in private groups, but some of it easier for luxury brand owners to access.

The social web is still a relatively young space and one that should not be ignored. Luxury companies do need to be online, as we discussed in chapter five, and to use the technology to tie customers to the brand and its image. Social web media offers companies a unique opportunity to allow their customers and passionate but attitudinal-only brand ambassadors to do some of the heavy lifting in marketing. The most controllable way is to open up and keep fuelling presences in social networks such as Facebook and Twitter, or their more elite and regional relatives across the globe.

“Controllable” means that the luxury brand owner can steer look and feel, content, access and many other aspects. Sure, anything a company posts is intensely scrutinised and targeted to convey a specific message, but the reaction can only be moderated to a certain extent. Since luxury companies create superlative products, experiences and services, the reaction does not necessarily need to be feared – as long as the company authentically, honestly, transparently and consistently lives up to its own value and the expectations raised within the customer and ambassador group.

“Fuelling” means the nurturing of this online presence with news, text, pictures and videos. Even for the vast majority of luxury brands, just providing the frame for a community means that it will develop automatically and, without continuous investment, add value to the loyalty programme or brand. Many luxury companies, including jewellery house Tiffany & Co., have had extraordinary reactions to their online efforts. Fans jump onto corporate posts to heap praise on the company and its products. This needs to be leveraged and used. Tiffany created a “True Love” campaign on Facebook that featured real photos and stories from customers. This created an emotional bond and 5 million “likes”, and went a long way to bind customers. The campaign seemed to spread the message that Tiffany does not just care about its products, but also about who is using them and why. A very positive message, and much of the work was done by customers themselves. “I challenge the luxury brands to consider how to involve these types of customers as more than fans on social media. Invite them into a community that means something. Create intimacy. Reward the passion,” says Jeannie Walters, chief customer experience investigator and founder of 360Connext, a Chicago customer experience consultancy.

There are exciting opportunities here for deepening and stabilising the relationship to luxury brands, while at the same time feeding the data engine of the loyalty programme and enhancing customer experience through superior knowledge. But luxury brands can do much more in the digital sphere. For example, they can provide information, audio-visual content or even products for review to bloggers, newsgroup administrators and other muliplicators. The response will usually be positive reviews and posts, usually from attitudinal ambassadors rather than customers, that further enhance a brand’s fame and reach. The flip side of this approach is that the brand owner has less control and will receive less information to feed the loyalty programme. Gamification offers unique ways to connect and interact with luxury brand target groups who are living and shopping more online than offline. Here the brand owner stays more in control and benefits more from data generated. And, not least, even luxury brands can dare to sell their products and services online. Again, this is either more controllable in the brand’s own online shops, providing more information for the loyalty programme. Or it is less controllable and less beneficial for the loyalty programme via third-party online stores. Many companies are already using these methods or similar technologies. But the real challenge is the smart and real-time linking of data across all the sales channels of a company. If a luxury brand wants to provide a truly seamless shopping experience, the same data should be available at every point of sale, be it online or offline, mobile or stationary. This includes a wide range of data about products, shipments, availability, regular customers and other things.

Especially with respect to online communities, there is another fine line to be walked. Luxury is built on exclusivity and restricted access for elites, while the Internet is removing barriers and democratises access. It makes sense to use web-based communities to intensify relationships with and knowledge about the chosen few customers, prospects and ambassadors, but overcome the temptation to reach out to “everybody”, as this would surely dilute the brand.

CARS AND LOYALTY

Within the automotive sector, luxury cars enjoy the highest loyalty. Premium and mass-market manufacturers dream of the kind of loyalty that luxury auto brands have created. Because cars represent some of the biggest purchases made by luxury buyers, they are also some of the most infrequent. It is easier to be fickle with €4,000 handbags than with cars that cost half a million. Therefore, automotive luxury studies offer a fairly transparent view of what works and what does not. With cars, two things are vital to buyers: brand affinity and quality/reliability. Manufacturers that can offer extreme levels of quality and reliability create lifelong fans – for what would be more embarrassing than showing up at a meeting of high-end car aficionados only to have the sunroof get stuck on your latest €500,000 machine? It is also important to deliver this level of quality to brand lovers. Hell hath no fury like an enthusiast scorned. We are talking cars, but this is true for most sectors: quality and reliability are king. Interestingly, the reasons for brand loyalty differ among individual brands, highlighting the need to know exactly why your customers like you. Mercedes-Benz buyers, for example, love the brand’s prestige but also remain loyal because of reliability (see infographic on page 213).

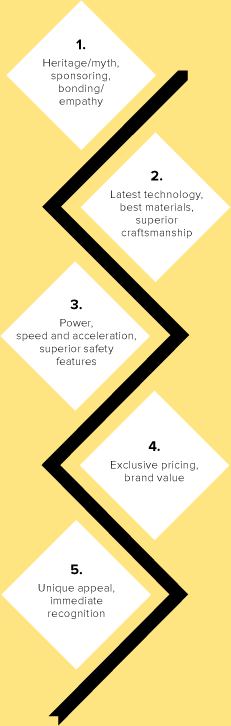

Top five factors affecting luxury automotive purchases

Luxury cars are as much about image as performance.

Source: own research

This is all well and good. But there is something more here than the focus on DQR (durability, quality, reliability) – something that makes the luxury car buyer a different animal than the mainstream compact car buyer who actually has to depend on his car. BMW drivers appreciate the company’s image but also want performance from their sedans. Brand and the power of the engine certainly are among those differentiators. It was mostly for brand reasons that Volkswagen’s luxury sedan, the Phaeton, did not become the success it looked like becoming just from its undoubted quality. Similarly, the obvious use of more reliable Ford parts has almost killed the Jaguar brand. And looking at the power that comes in Bugattis, Bentleys, Rolls-Royces, Ferraris, Lamborghinis – the power level delivered is in line with the real or perceived power levels of its buyers.

Limited access to luxury cars (by numbers produced, purchase price, servicing costs) is important to demonstrate to the luxury buyer how far he is above the crowd, how much a part of the chosen few. Heritage, myth and visibility in the luxury shopper’s peer group are key for loyalty. One important caveat regarding automotive brand loyalty is the difference between men and women. Women remain loyal because of an exceptional dealership and service experience. This is one area where carmakers should make conscious decisions to discover just who is doing the shopping – and also create special buying and after-sales experiences for women. Other businesses catering to both sexes should consider doing the same. This is true concerning the balance between the superiority of the luxury product and the second-best in the company’s portfolio, the right service levels granted and premiums charged.

For Bugatti this is all in sync, but for the Maybach revival that was not the case. The product was too close to the regular Mercedes-Benz S-Class. And the 24/7 concierge service accompanying the Maybach was not relevant enough for the predominantly male target group, despite being set up with high-end loyalty technology in the background and a human (the personal concierge) delivering it to the customer. As a result, the premium charged for the Maybach was not justifiable for luxury buyers. The heritage and myth of the Maybach brand have not been strong or desirable enough to close the gap, neither for the initial purchase nor – especially – in nurturing loyalty.

CASE STUDY

Five examples of rewarding

customer loyalty

We’ve established that luxury consumers cannot be bundled into a homogeneous group. But what unites them is that they like their loyalty to be acknowledged. Let us look at five ways in which luxury brands pay back their customers.

1. HON Circle

Lufthansa’s elite frequent-flyer programme offers such exceptional rewards that some travellers find themselves splashing out on first-class trips or even charter jets just to maintain their status. Although HON Circle members are essentially afforded the same luxuries as the carrier’s first-class passengers, they are given priority servce – the extra helping that makes the HON Circle so elite.

2. Lanvin

Limited editions are an established business model for creating a bond between customer and brand. Fashion house Lanvin has taken it a step further by producing a limited edition available only to valued customers for a specific time. A handbag made from black python leather, with a price tag of $4,000, was sold to top customers at Lanvin’s Mount Street store in London. Only 14 were made – a number that says, “You, the customer, are special to us”.

3. Gucci

Maybe it is no surprise that a brand known for flamboyant fashion also treats loyal customers extravagantly, offering big spenders the kind of access usually reserved for celebrities. For instance, a select handful of A-list shoppers gets invitations to the menswear show in Milan with a seat in the front row and accommodation in a first-class hotel. A fitting for a custom-made suit, and private tours of the Gucci Museo in Florence and the Gucci Casellina workshop are also included. Smaller tokens of appreciation, such as leather accessories, are dispensed throughout the trip. Gucci has also been known to invite customers to the Cannes Film Festival and equestrian events. It is a way to make the customer feel good about their spending, a “thank you” from Gucci that is also meant to encourage further spending.

4. Mr. Porter

The brother of online shopping giant Net-A-Porter carries an unparalleled selection of luxury menswear and accessories, from Balenciaga to Dolce & Gabbana to Valentino, mixed with classic sportswear and contemporary brands. Whatever the taste of the customer, and however small or large the purchase, the item arrives wrapped in black silk paper and sealed with a customised sticker bearing the customer’s name. The gesture indulges the shopper’s vanity and shows him that the company’s appreciation does not end when the customer clicks the buy button.

“Customers

want an exchange

with brands.”

An interview with Lutz Bethge, non-executive

chairman and head of the supervisory

board of Montblanc, which has successfully

diversified beyond writing instruments.

Luxury brands used to know exactly who their customers were. Is this still true today?

This has changed greatly over the course of time. Going back, it was actually the nobility, in other words sovereigns, kings and princes, who invented luxury as a part of their personal lifestyle. They hired the best craftsmen of their region, country or even of the world, to create something special for them. Customers like this are no longer around. Today we see the “financial aristocracy”, the ultra high net-worth individuals (UHNWs) and the high net-worth individuals (HNWIs). They are completely immune to crisis, are highly demanding and very much interested in made-to-order products and services. But of course, they are quite a small target group. Then there are the “old money” customers who have acquired a particular lifestyle over generations and are mainly conservative. At Montblanc we call them “conservative achievers”. This group is somewhat larger. The luxury industry’s success over the last 20 or 30 years has been to use brands to bring the luxury’s elite range to the “aspirational customer”. Because today, the trust we once placed in craftsmen has shifted over to brands. And the brand is hopefully authentic, and with its value, offers customers what they want.

Who do you include as aspirational customers?

This group is at least twofold. On the one hand, there are the so-called “elite of tomorrow”. In the 1980s they were known as yuppies. In principle they have similar conservative thought patterns as the “old money” group. For example, a profession, career, earning money, the black Porsche as a status symbol. They want to show that they’ve made it. In emerging markets there are many people who fall into this first segment. Montblanc is extremely successful in the developing markets. With a product for less than €1,000, you can still symbolise a cultivated, sophisticated and successful luxury lifestyle. For other companies, this often starts at several thousand euros.

You spoke of the two groups of aspirational customers…

In mature markets such as Europe and North America, but increasingly in developing markets as well, there is a new type of “aspirational customer” who advances through the story much faster. They no longer rely exclusively on the revered, traditional status symbols. Instead, they live a different lifestyle and value a work-life balance. They want to be surrounded with items that fit their lifestyle, things which are beautiful, authentic and sustainable. All of these play a bigger role, but what it finally comes down to is status. Luxury is always the aim, but status can also mean that I’m living a lifestyle that is very creative or one in which I become familiar with interesting products.

![]()

The trust we once placed in craftsmen

has shifted over to brands.

And the brand is hopefully authentic.

![]()

How do I get these different target groups to become loyal customers?

Authenticity is of utmost importance. This includes craftsmanship, which also needs to be represented. In 1997, when Montblanc entered into making watches, we chose the path of taking on the production process ourselves. We made a conscious decision back then to build a manufacturing facility in Switzerland, and to produce watches where the expertise and experience has been present for generations. It was a signal to customers that we mean business.

Don’t new Montblanc product categories carry a danger of diluting the brand and irritating loyal customers?

When we develop products, it’s important to us that they’re new, modern and creative, but the customer should still love that product in 10 or 20 years’ time. On the one hand there is fashion, a short-term pleasure which is popular and important to everyone. But then there are things that have a companion quality. That’s what we produce. This quality must not only be reflected in longevity. The desirability of a product must also be maintained over many years. For example, my writing instrument is a Montblanc pen that I received 24 years ago before I came to the company. It was a gift from my girlfriend at the time. She is now my wife, by the way.

The message of authenticity and timelessness – is this told the same way in all markets?

The core message, yes, but sometimes it takes on different forms. For example, we entered China in the mid-1990s. And right from the start, exclusively with our own shops, where you could experience our brand as a whole. As a result, we created a very select distribution. We deliberately utilised mega-events as a means of communication. In a market that doesn’t yet know much about a brand’s story, you need to do two things. On the one hand, you explain the story because in developing markets people want to buy what’s “right”. But in the beginning, they don’t know the story. On the other hand, we wanted to communicate that Montblanc is a major brand. We achieved this through events for up to 3,500 VIP guests. We built a Montblanc city at a film studio outside Shanghai for our 100th anniversary. There was a Montblanc mountain that you could ski down, a Montblanc tramway and a Montblanc café.

Does digital storytelling work differently?

That is certainly the case. For example, we used an Internet campaign with Wim Wenders for our watch collection that we called “The Beauty of a Second”. In a short trailer on our website, Wim Wenders spoke of how everyone has the potential today to make their own films. Then he announced a competition and invited filmmakers to submit their “most beautiful second”. We received tens of thousands of entries. The “Most Beautiful Second” and the “Most Beautiful 60 Seconds” won awards, and a viral campaign went global. This was a different way to access the brand and created a much more open and playful image. This is positive because Montblanc is seen as a serious brand having a certain gravitas. I really struggled with e-commerce for many years. A complication is the fact that suddenly customers are buying on the Internet and no longer in the shops. The shops are, however, important for us in order to have a dialogue with the customer. But also because we find that products bought on the Internet and in shops tend to be different ones: a customer will, for example, buy a smaller gift online – and have it sent directly to a friend – but nevertheless continue to buy high-ticket items in a shop.

![]()

Today, by purchasing a luxury brand

you’re buying a piece of a world.

The question now is: How attractive is this world

and how can I renew it regularly?

![]()

As a luxury brand, you also need to be a digital storyteller, and these stories must be authentic and verifiable, right?

At the same time, you need to have a certain amount of sustainability today, because especially during tough times, people who spend thousands of euros on a watch could be viewed ambiguously. Successful brands or successful companies must give something back to society. Examples are our activities with UNICEF, who we are helping in the fight against illiteracy, or our cultural projects, such as the Montblanc de la Culture Arts Patronage Award, which honours individuals who have distinguished themselves as modern patrons. This offers us the opportunity to present ourselves as a brand in a cultivated environment. Our most loyal customers want to keep up a strong dialogue with the brand. That’s why we create experiences with our events. I’ve just returned from Beijing where pianist Lang Lang, chairman of the Montblanc de la Culture Foundation, played for 300 guests at a dinner and also was available for casual, interesting conversations.

By purchasing a luxury item, I’m also part of a world. Is this becoming more important or was it always like this?

I think it’s become much more important. It used to be that a craftsman enriched a particular customer’s world. Today, by purchasing a luxury brand you’re buying a piece of a world. The question now is: How attractive is this world and how can I renew it regularly? How can I keep finding creative new ways to say something different about the same thing? That is a fine line. You have to constantly be thinking of new ways to bring people together, how to excite them and how to reach them digitally. At some point during my time as CEO at Montblanc, I decided to set up an official Montblanc CEO Facebook page where I replied to posts from customers personally. It turned into a meeting point for satisfied and dissatisfied Montblanc customers. I find that exciting.

![]()

You have to constantly be thinking of new

ways to bring people together, how to excite them

and how to reach them digitally.

![]()